Welcome to #CCPinCEE, a series of reports published by the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA) analyzing Chinese influence efforts and operations across the nations of Central and Eastern Europe.

Executive Summary

- The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) takes an opportunistic approach to Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). It targets central governments where possible and other sources of political, cultural, and economic influence where necessary.

- The CCP minimizes its effort, not seeking to understand complex local power dynamics or economic, cultural, historical, and geographical differences.

- This minimalist approach enjoyed moderate initial success when it offered easy money at low political costs. It is less effective now and fails more often than it succeeds.

- Chinese influence efforts exploit existing divisions in society. Key target audiences are political and economic elites and academics.

- The CCP seeks to exploit “gaps” that national governments or international organizations have failed to address, including in infrastructure, financial support, and pandemic-related health care (vaccines and personal protective equipment).

- Countries outside big international organizations, such as the European Union, are more susceptible to Chinese influence.

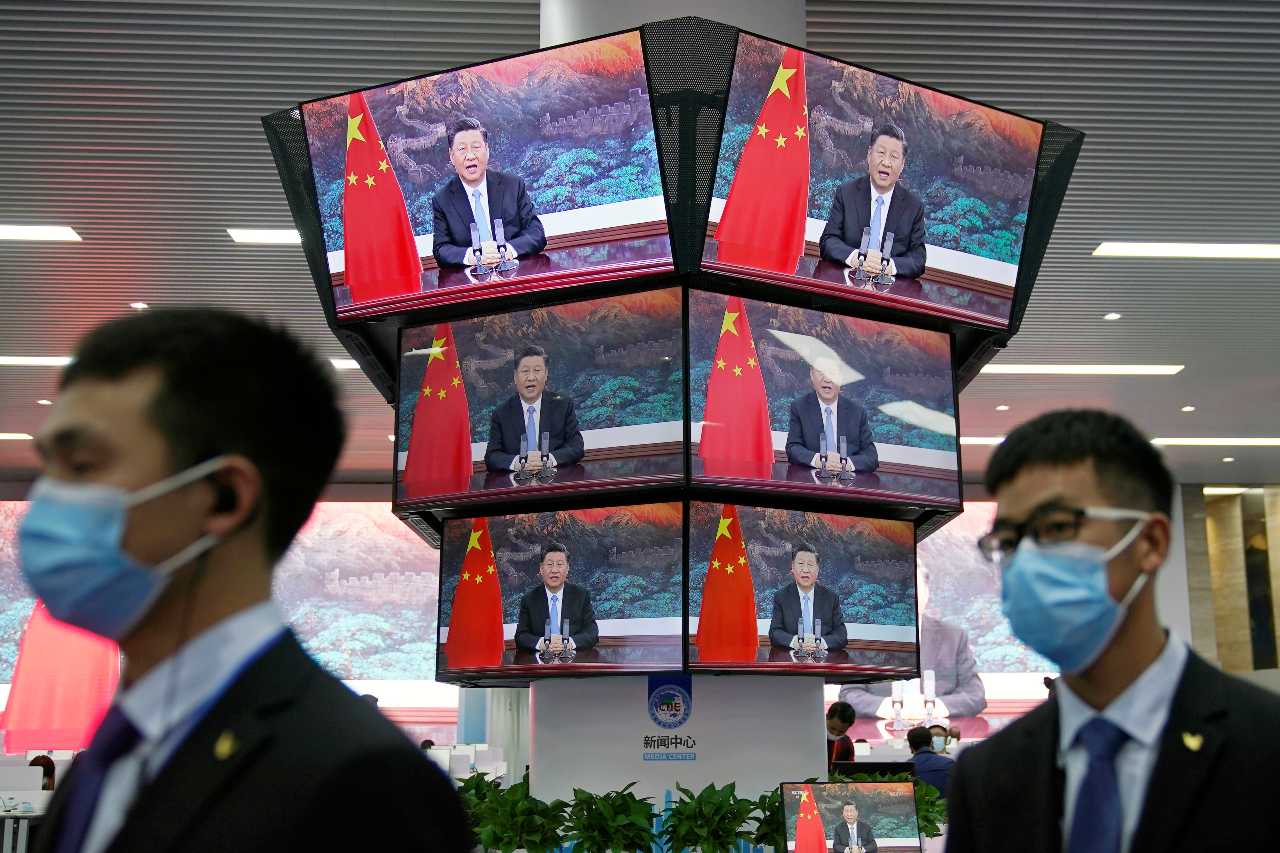

- The CCP finds it easier to promote a negative, anti-Western agenda rather than a positive (pro-China) agenda. Many illiberal governments in the region opportunistically use Chinese support for domestic political purposes. Some independent media and civil society investigate and decry Chinese influence.

- The CCP tolerates its limited success rate, as its investments are low-risk and offer potential long-term rewards.

Introduction

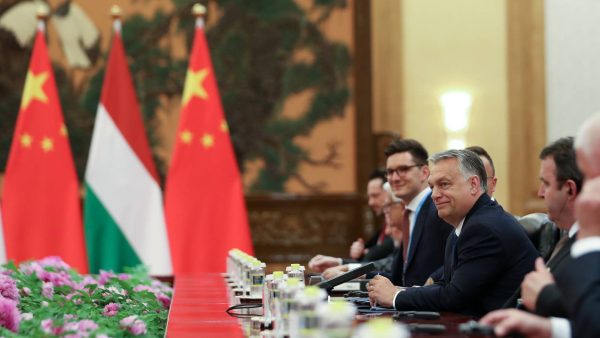

Little consistent pattern emerges at first sight from Chinese influence operations in the CEE region. They target big countries (Poland and Romania) and small ones (Montenegro, Estonia, or North Macedonia). Sometimes they use economic means (as in Hungary and the Western Balkans, and in coercive pressure on Lithuania) and sometimes they wield diplomatic or soft power (Poland). They chime with local political objectives (Serbia and Hungary) and cut diametrically across them (Czech Republic and Lithuania). They are systematic (Serbia) and dilatory (Romania). What they have in common are a minimal use of effort and a concentration on centers of power where possible, with a punitive approach to political decision-makers who violate the party’s taboos on issues such as Tibet and Taiwan.

Coupled with this confusion are other ones about strategy and long-term aims. Does China intend to expand the 16/17+11 platform? If it can stretch to include Greece, then why not Austria? If it includes non-EU countries in the Western Balkans, then why not Ukraine, Moldova, or Belarus? Is the eventual aim to make it a 20+1? Or even bigger? Is it primarily an operation of economic influence — which is, after all, the China’s strongest suit — with any political or diplomatic elements to come later? Within the economic framework, what is the relative importance of trade over investment? How big of a carrot is access to the Chinese market in promoting Chinese exports? If the real aim is political and diplomatic, then what is the goal? Is it to disrupt EU decision-making and plant Trojan horses within Western structures? What is the role of the 16/17+1 offices set up in some host country ministries? And what about soft power?

From a conventional Western standpoint, this confusion and haphazard implementation could look like a serious strategic failure for the CCP. If the United States were to take this approach to Latin America or African countries, for example, one would expect searching scrutiny in the media and from the Congress.

The confusion and failure also belie Western concerns. After a promising and uncontroversial start in 2012, the 16/17+1 initiative attracted intense scrutiny from think tanks, policymakers, and intelligence services. Amid deepening chills in Sino-US and then Sino-EU relations, it sparked fears that China is seeking to divide Europe and weaken the transatlantic alliance by exerting influence in the CEE region.

The audit of Chinese efforts in the pages that follow can be taken as a litany of failure that allays any further concerns about Chinese influence in the CEE region. It is clear that the Chinese Communist Party leadership does not understand the economic, cultural, historical, and geographical differences within the supposed CEE region. Nor does it have any experience anywhere in the world of successful multilateral diplomacy. The story in the CEE region merely underlines this. In short, the party’s tailored country-by-country approach fails far more than it succeeds, and it has failed to create a regionwide approach, either.

But a different analytical framework supports a less complacent conclusion. China takes an opportunistic and patient approach. It is not working toward a specific goal, and it does not start by assuming that the region is a financial, diplomatic, or soft-power priority. Its approach varies country by country precisely because it is testing the water. Some things work. Other things do not. The decision-makers in Beijing watch, listen, and learn.

The main approach is “gap-filling.” Where an opportunity presents itself (for example in the supply of vaccines and other COVID-19 related materials), the Chinese government offers them. If a tempting investment opportunity arises, it seizes it. If an infrastructure project offers high-profile and political gains, China steps in. If there is domestic anti-Westernism, China endorses and seeks to amplify it. The pushback is limited. In some countries, robust civil society and independent media engage in groundbreaking research and investigative journalism to call out China’s increasing influence. In Hungary and Serbia, illiberal governments are happy to use Chinese support to boost their domestic political capital and as leverage in relations with the EU and United States.2

None of this is guaranteed to work soon, or to last sustainably. But some of it could bear fruit at some point. From China’s point of view, that is already a reasonable return on a limited investment of time and money.

The real point about this fill-the-gaps strategy is that these gaps exist because of the failures of other international institutions and governments (such as the EU, US, and International Monetary Fund). Put crudely, China advances where Western countries and institutions fall short, for example capitalizing on disillusionment in the Western Balkans about the stuttering pace of EU enlargement. If Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Albania were already in the EU, or very close to joining, China likely would have fewer opportunities to exert influence (though Germany, a core EU country, is a prime example of successful Chinese influence operations). If Western pressure had already curbed Victor Orbán’s headstrong foreign policy, the Hungarian leader would be far less likely to flirt with the Chinese (and Russian) governments. If other Western countries took a more robust approach to Taiwan, Lithuania would be less exposed (that economic coercion against Lithuania has gone unpunished is seen as a major success in Beijing). If existing academic institutions taught Chinese language, culture, and history properly, there would be no scope for the Confucius Institutes.

These self-inflicted failures present opportunities for malign Chinese influence operations, including corrosive capital, strategic corruption, information operations, and diplomatic divide-and-rule gambits.

Against this background, this research paper explores Chinese influence operations in current or former member countries of the 16/17+1, with case studies written by top experts in each country. The authors explore the overall goals and objectives of the Chinese Communist Party’s malign influence operations; the party’s methods, tools, and tactics for advancing malign influence; the reach of its tactics; and its target audiences and populations. While the focus of the exercise is on malign influence — coercive or corrupting activities that disrupt the normal political processes in a targeted country — the report also covers broader influence measures.

Only by understanding the scope and nuance of China’s approach to the region can policymakers on each side of the Atlantic counteract it.

Note About Malign Influence

According to 50 US Code § 3059, malign influence can be described as “any hostile effort undertaken by, at the direction of, or on behalf of or with the substantial support of, the government of a covered foreign country with the objective of influencing, through overt or covert means.” 3

The original scope of this project was to examine malign Chinese influence operations in the 16/17+1 countries. Throughout the course of the project, the experts found that the sphere and extent of influence across the region varies significantly. Instead of focusing on malign influence, the in-country experts focused on means of influence that China uses to manipulate the conversation in the respective country. This report details their findings.

Countries

Acknowledgments

This report is the result of research contributed by 17 independent in-country researchers. All opinions are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the position or views of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA). A special thanks to Mareike Ohlberg for her thoughtful feedback. This work was made possible with the generous support of the United States Department of State.

- The original 17+1 initiative recently shrank to 16+1 as Lithuania left the initiative in 2021. Since this report focuses on the original 17 countries, this report will refer to the initiative as 16/17+1. [↩]

- “Orbán: If EU Doesnʼt Pay, Hungary Will Turn to China,” Budapest Business Journal, January 11, 2018, https://bbj.hu/economy/orban-if-eu-doesnt-pay-hungary-will-turn-to-china_143836. [↩]

- “Definition: Foreign Malign Influence,” Legal Information Institute, accessed July 6, 2022, https://www.law.cornell.edu/definitions/uscode.php?width=840&height=800&iframe=true&def_id=50-USC-690777767-2037611553&term_occur=999&term_src=title:50:chapter:44:subchapter:I:section:3059 [↩]