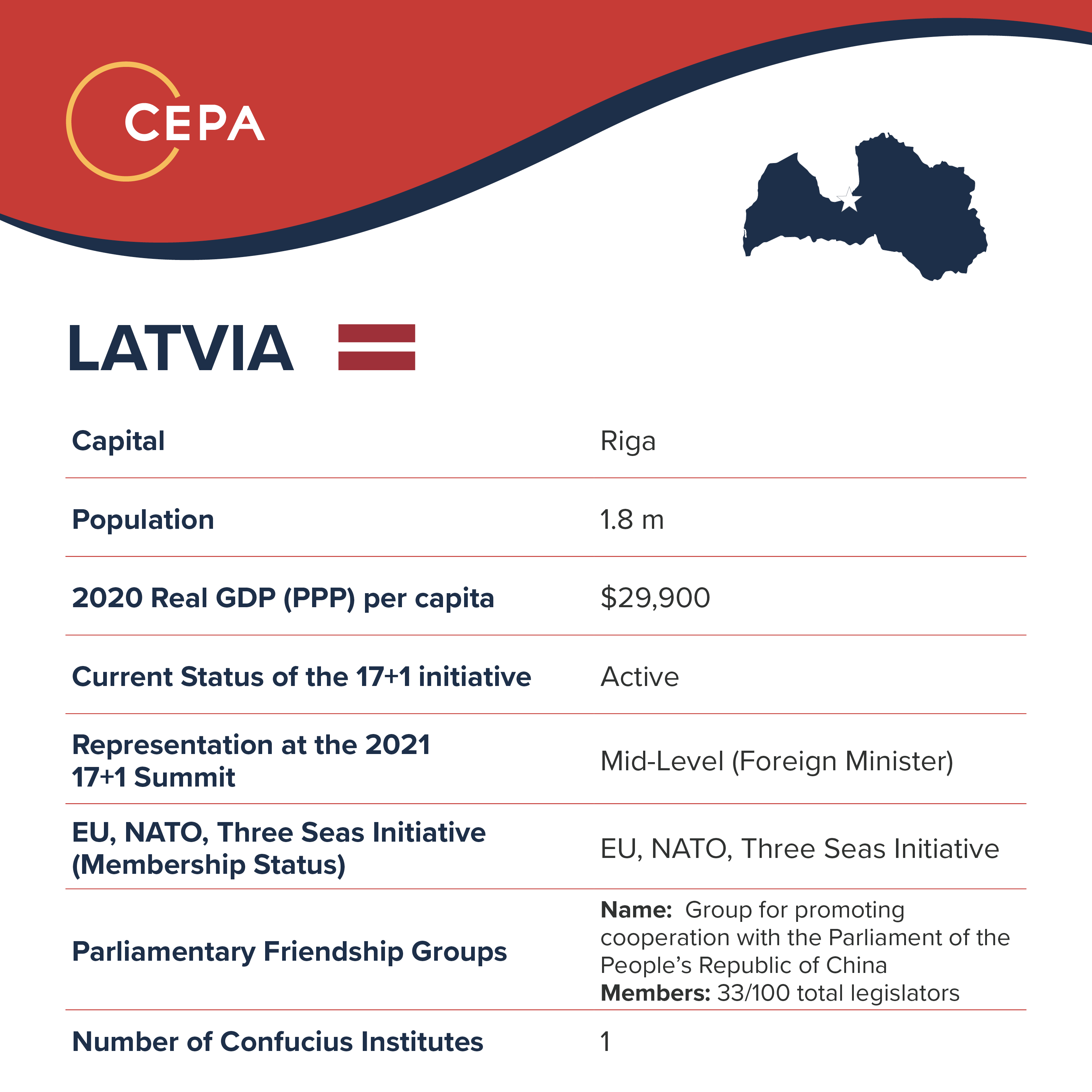

This report is a part of #CCPinCEE, a series of reports published by the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA) analyzing Chinese influence efforts and operations across the nations of Central and Eastern Europe.

Goals and objectives of CCP malign influence

Chinese malign influence efforts in Latvia so far have been relatively passive. The goals are primarily to create a positive image of China, gather information on and establish contacts with the political and economic elite, and probe possibilities for major investments in Latvia. The State Security Service, which is in charge of counterintelligence in Latvia, has observed increased activity and interest from Chinese intelligence and security services. According to the Security Service, China’s goals are twofold: to “obtain information about processes in NATO and EU, as well as distributing favorable information, justifying China’s foreign policy and lobbying closer cooperation with China.”1 Chinese activities also seek to repair the country’s public image in regard to COVID-19 and to gather information about people and organizations critical of China. 2

CCP’s methods, tools, and tactics for advancing malign influence

The Chinese Embassy in Latvia is the key player in advancing covert and overt malign influence in Latvia, via a network of affiliated organizations, especially in academia, economic investments, and information operations.

The Confucius Institute and the Chinese Embassy are active within the three most prominent universities in Latvia. Officially, the institute, which has been embedded within the University of Latvia since 2011, aims to promote the Chinese language and culture and to facilitate student and faculty exchanges.3 From 2011 to 2019, the university received $700,000 from China in support of the institute.4 At Riga Technical University, the Confucius Institute and the Chinese Embassy have established a Confucius Classroom, with a library, Chinese language studies, and student exchanges.5 Riga Stradins University, which established its own Confucius Center in 2005 and translated its webpage into Chinese, aimed to attract students from China through “successful cooperation with the Chinese Embassy.”6 In addition, 14 schools in Latvia hosted Confucius Classrooms (Chinese language study programs) as of 2019.7 The University of Latvia’s Confucius Institute is run by a sinologist, former diplomat, and KGB agent, Peteris Pildegovics.8 Latvia’s security services warn that it poses intelligence risks and is disseminating ideological messages favorable to China’s Communist Party. There have been accusations that the institute gathers information on students involved in its activities.8

There are three other active organizations associated with Chinese influence in Latvia. The China Cultural Center opened in 2015 with the goal to popularize Chinese culture through various events, such as art exhibitions, movie screenings, seminars, and the like.9 These events are attended by some in Latvia’s political and economic elite, especially members of the Kremlin-leaning Harmony party. The Economic and Commercial Office of the Chinese Embassy in Latvia works on the promotion of trade and facilitates relations with political and business leaders of Latvia. It has also published and allegedly bought articles in Latvian media touting China’s growth, supporting increased trade with Latvia, and presenting China as an active and responsible global leader.10 The Chinese Embassy supported and organized the China Alumni Association of Latvia for students who used to study in China, even though the organization is portrayed publicly as a grassroots movement. Students who have studied in China have been used to send political messages to Chinese audiences, such as showing that there is support for China abroad as the country weathered international accusations that it hid the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic.11

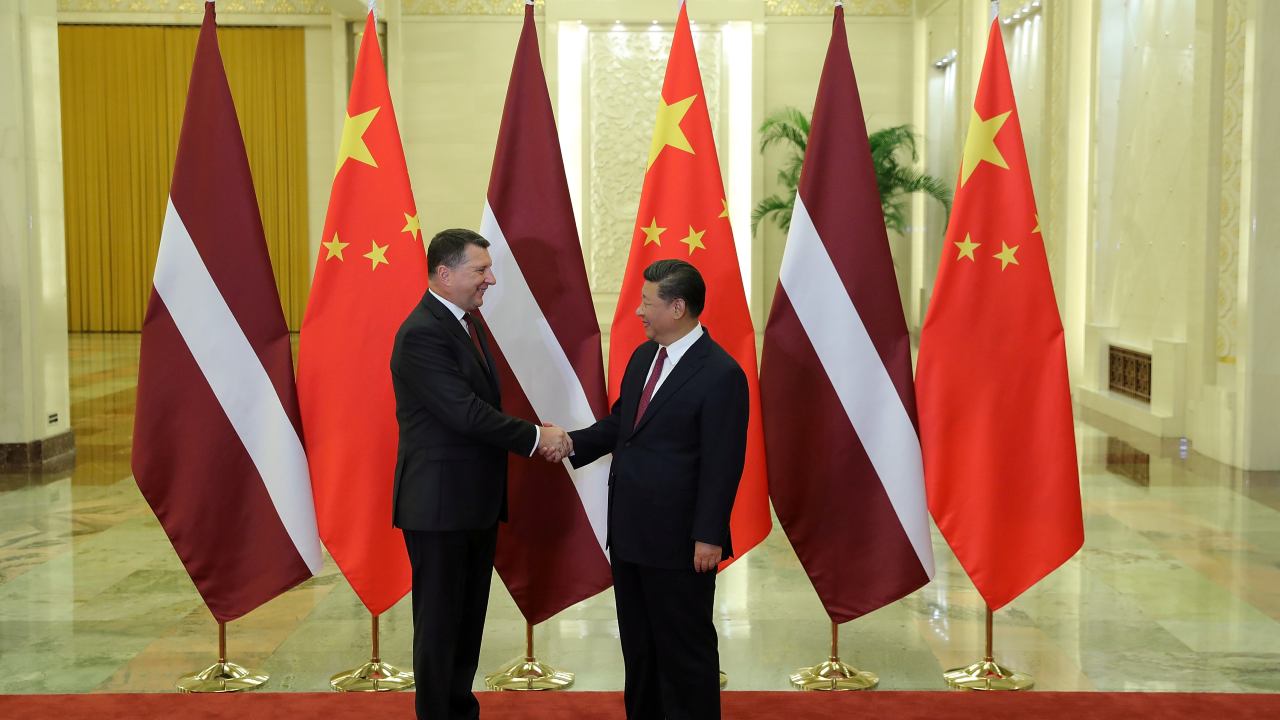

Riga hosted the fifth 16/17+1 summit in 2016, which like other gatherings of this grouping produced little. Around 2016, China tried and failed repeatedly to invest in infrastructure and various strategic sectors. The most notable attempt involved Rail Baltica, the biggest infrastructure project in the Baltic countries.12 Chinese officials had hoped to build the entire project, but their interest cooled upon learning that Rail Baltica construction would happen via a series of competitive tenders.13 As of 2018, Chinese investments in Latvia amounted to only $65 m, or 0.39% of foreign direct investment.

Only three investments have raised red flags due to their strategic importance: Chinese citizen Huang Jianhua’s ownership of approximately 40% of Factum Interactive, one of the oldest polling agencies in Latvia; a research and manufacturing plant built by Chinese genomics research company MGI near Riga International Airport8 ; and Bite Latvia, one of the country’s three mobile operators, which in 2016 agreed to work with Huawei to build a 5G network in Latvia.14

The most prominent promoter of Chinese interests in Latvia has been the state-owned railway company, Latvijas Dzelzceļš (LDZ), which covets the profits from moving Chinese cargo. Around 2016, LDZ started talking up trade with China. It has paid domestic think tanks to portray China positively on Twitter,15 created and posted promotional YouTube videos,16 written articles, and given interviews that supported the Belt and Road Initiative.17

The State Security Service’s 2020 annual report states that “China systematically carried out activities in order to fill Latvia’s information space with narratives compl[i]menting China and create a positive attitude about China in Latvia’s media environment.”18 Chinese narratives discrediting NATO and the EU often overlap with Russian information operations. According to the Security Service, Kremlin-affiliated online disinformation sources such as Sputnik and lv.baltnews.com disseminate pro-China messages.19

The security service report also states that China conducts “aggressive information influence activities.”8 Journalists agree that although the Chinese Embassy in Latvia seldom responds to their questions,20 any news outlet that publishes an extensive critical article on China will likely receive a letter of protest from the Chinese Embassy. Some local media with lower standards have repeatedly published flattering interviews and even articles paid for by the Chinese Embassy. For example, in November 2019, Latvijas Avīze (the fifth most popular online news outlet in Latvia) and Neatkarīgā Rīta Avīze (the ninth most popular news outlet in Latvia) published an article paid for by the Chinese Embassy titled “Kādu pasauli Ķīna aicina veidot?” (What kind of world is China calling for?) that was essentially a two-page advertisement for China.21 While Latvijas Avīze clearly indicated that the Chinese Embassy paid for the article, Neatkarīgā Rīta Avīze did not.22

Sources: The World Factbook 2022, (Washington, DC: Central Intelligence Agency, 2020), https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/; World Bank, The World Bank Group, 2022, https://www.worldbank.org/en/home; “Groups for promoting cooperations”, Republic of Latvia 13thSaeima, Retrieved June 27, 2022, https://titania.saeima.lv/personal/deputati/saeima13_depweb_public.nsf/structureview?readform&type=DG1&lang=EN&count=1000

Reach of influence measures

The activities carried out by these various organizations are persistent and ever-increasing. Activity picks up further when Chinese government officials visit around important dates or events. Still, these operations have not resulted in any major investments from China, and their effect on the overall population is limited, with some exceptions described below.

Targeted audiences and populations

Based on survey data, roughly one-tenth of Latvia’s population could be highly susceptible to Chinese narratives and supportive of the Chinese political regime. A third of the population thinks well of Chinese culture and influence. Most vulnerable to Chinese influence are critics of Latvia’s democracy, the West, and Western values and people who already have an interest in China and are interested in traveling to China for business, culture, or educational exchanges. Native Russian speakers as well as members of Kremlin-leaning political parties Harmony and Latvian Russian Union are also more sympathetic to China.

As mentioned, Kremlin-aligned news outlets often disseminate pro-China messages, omitting mention of human rights issues and shortcomings in democracy or the rule of law in Russia and China.23 Thus, native Russian speakers (36% of Latvia’s population) are more open to Chinese narratives. In a 2020 survey,24 two-thirds of the Russian-speaking respondents thought well of China. That is 30 percentage points higher than the share of Latvian-speakers who took a positive view of China (32%). Almost 30% of all respondents thought China is culturally attractive and 30% agreed that China is important for the economic development of Latvia. Only 9% of respondents, however, thought that the human rights situation in China is positive, and less than 7% trusted China. In the GLOBSEC Trends 202125 survey, carried out in March 2021, 17% of respondents believed that the Chinese political regime could be an inspiration for Latvia.

Conclusion

Generally, China wields little influence in Latvia, even as it has repeatedly tried to be a bigger player in the country. China has attempted, unsuccessfully, to get a piece of some major investment projects in Latvia in recent years. The Chinese Embassy and its affiliated organizations have been working to develop ties with local political leaders and to sway public sentiment, but they have managed to develop ties only with Kremlin-leaning opposition parties. Although a few domestic news outlets occasionally disseminate pro-China messages, Latvia’s major news organizations cover China objectively. Only about one-tenth of Latvia’s population has an uncritical, positive image of China. China’s biggest footprint could be in Latvian higher education, with Confucius Institutes operating freely and the Chinese Embassy supporting various projects in universities.

- Latvian State Security Service, “Annual Report for 2020,” 2021, 7, https://vdd.gov.lv/en/?rt=documents&ac=download&id=59 [↩]

- Ibid, 8. [↩]

- “Confucius Institute,” University of Latvia. https://www.ki.lu.lv/par-mums-1/ [↩]

- Liepiņa et al “The Rough Face of China’s Soft Power,” Re:Baltica, September 2019. https://en.rebaltica.lv/2019/09/the-rough-face-of-chinas-soft-power/ [↩]

- “RTU atklās Konfūcija klasi,” RTU, November 4, 2019, https://www.rtu.lv/lv/universitate/masu-medijiem/zinas/atvert/rtu-atklas-konfucija-klasi [↩]

- Dace Skreija, “Rīgas Stradiņa universitāte grib apmācīt ķīniešus,” Dienas Bizness, April 17, 2012, https://www.db.lv/zinas/rigas-stradina-universitate-grib-apmacit-kiniesus-370303 [↩]

- Liepiņa et al. “The Rough Face of China’s Soft Power,” 2019 [↩]

- Ibid. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- “Rīgā dibinās Ķīnas Kultūras centru,” LSM, November 17, 2015, https://www.lsm.lv/raksts/kultura/kulturtelpa/riga-dibinas-kinas-kulturas-centru.a155395/ [↩]

- Šen Sjaokai, “Šen Sjaokai: Pieci svarīgi jautājumi par Ķīnas un Latvijas tirdzniecības sadarbību,” Delfi, September 24, 2019, https://www.delfi.lv/news/versijas/sen-sjaokai-pieci-svarigi-jautajumi-par-kinas-un-latvijas-tirdzniecibas-sadarbibu.d?id=51480949 [↩]

- China Alumni Association of Latvia, “Mēs esam pret rasismu, dezinformāciju un paniku ! #fightvirusnotchina #turieskina #中国加油!中国加油”Facebook, February 6, 2020, https://www.facebook.com/793304950806650/posts/1740643626072773/ [↩]

- Rail Baltica web page, “Rail Baltica – Project of the Century,” https://www.railbaltica.org/about-rail-baltica/ [↩]

- Navakas et al. “The Golden Handcuffs of Chinese Investment,” Re:Baltica, September 5, 2019, https://en.rebaltica.lv/2019/09/the-golden-handcuffs-of-chinese-investment/ [↩]

- Roonemaa et al, “Weaving 5G Networks Amid Superpowers’ Battle,” Re:Baltica, September 2, 2019, https://en.rebaltica.lv/2019/09/weaving-5g-networks-amid-superpowers-battle/ [↩]

- Posts with New Silk Road hashtag (#NSR_LIIA) on LIIA twitter. https://twitter.com/search?q=NSR_LIIA&src=typed_query&f=live [↩]

- Latvijas Dzelzsceļš. “Rīgā svinīgi sagaida pirmo testa vilcienu no Ķīnas pilsētas Yiwu,” Latvijas Dzelzsceļš YouTube account, Nobember 5, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gp_uVictOJg [↩]

- “VIDEO: Latviju šķērsojis kilometru garš kravas vilciena sastāvs no Ķīnas,” LSM, April 9, 2020, https://www.lsm.lv/raksts/zinas/ekonomika/video-latviju-skersojis-kilometru-gars-kravas-vilciena-sastavs-no-kinas.a355370/ [↩]

- Latvian State Security Service, “Annual Report for 2020,” 2021 https://vdd.gov.lv/uploads/materials/8/en/annual-report-2020.pdf [↩]

- Ibid, 25. [↩]

- Sanita Jemberga , “Kādas ir Ķīnas intereses Baltijā?” LVPortāls, September 13, 2019, https://lvportals.lv/viedokli/308127-kadas-ir-kinas-intereses-baltija-2019 [↩]

- Latvijas Avīze and Neatkarīgā Rīta Avīze, “Kādu pasauli Ķīna aicina veidot?” Nov 22, 2019 https://nra.lv/citi-raksti/297726-kadu-pasauli-kina-aicina-veidot.htm [↩]

- “Kādu pasauli Ķīna aicina veidot?” NRA, November 22, 2019, https://nra.lv/citi-raksti/297726-kadu-pasauli-kina-aicina-veidot.htm [↩]

- Latvian State Security Service, “Annual Report for 2020,” 2021, 25. [↩]

- Bērziņa-Čerenkova and Una Aleksandra, “Latvian public opinion on China in the age of COVID-19,” Central European Institute of Asian Studies, 2021, pp. 9-10, https://ceias.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/LV-poll-report.pdf [↩]

- Hajdu et al., “Central & Eastern Europe one year into the pandemic,” GLOBSEC, 2021, pp. 28-29, https://www.globsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/GLOBSEC-Trends-2021_final.pdf [↩]