This report is a part of #CCPinCEE, a series of reports published by the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA) analyzing Chinese influence efforts and operations across the nations of Central and Eastern Europe.

Goals and objectives of CCP malign influence

Throughout the last decade, Poland and China have visibly strengthened their ties, both bilaterally and multilaterally.1 Beijing’s economic and political goals in Poland were intertwined from the onset (circa 2012, when the 16/17+1 platform was established), with China aiming not only to deepen trade and investment relations but also to strengthen the Chinese Communist Party’s legitimacy in the eyes of international audiences.

The party’s influence efforts have centered around two pillars: 1) attempting to establish local CCP-friendly proxies, including politicians and other public figures, and 2) influencing the domestic debate on China by promoting Beijing’s official messaging on issues crucial to the party’s interests through traditional and social media, public diplomacy, and people-to-people relations.

The last decade has witnessed China’s attempts to nurture a CCP-friendly environment in Poland. In the long run, this strategy aims to cultivate circles that share Beijing’s perspectives on vital issues and do not present a threat to its legitimacy, such as by voicing concerns about China’s poor human rights record or pointing toward asymmetric coercion in the face of the slightest criticism (as witnessed most recently by Australia2 ). The broader public has also become the target of Beijing’s image-building efforts through Chinese state-affiliated media and diplomats’ offensives in social media, most notably Twitter and Facebook.3

In the broadest sense, China has aimed to craft its image as a benevolent power retaking its rightful place in the international arena while not interfering in other countries’ internal affairs. While some have been seduced by this kind of rhetoric, the media and some politicians have contrasted it with the harsh reality of Chinese foreign and domestic policies. This has been especially true during the COVID-19 pandemic, as the coercive nature of Chinese politics, best epitomized by its “wolf warrior diplomacy,” has sown growing skepticism toward China.4 Moreover, because of the relative lack of tangible results of economic cooperation, Polish decision-makers have also grown weary of Chinese promises. As such, Chinese efforts to shape the public discourse to its advantage have faced ongoing challenges.

CCP’s methods, tools, and tactics for advancing malign influence

In Poland, China has focused on cultivating ties and exchanges with Beijing-friendly elites and public figures, as well as a strong public diplomacy push via Chinese government scholarships and youth cooperation projects, the establishment of Confucius Institutes, increased academic cooperation, and promotion of media content co-created by Chinese diplomats and state-affiliated outlets. The Chinese Embassy itself has actively championed Beijing’s official stance on many issues, with numerous op-eds by the Chinese ambassador in Polish media, most notably in the popular Rzeczpospolita daily newspaper and on the Onet news portal.5

So far, China has not resorted to direct coercive measures against Poland. Instead, it has used veiled threats and insinuations when tensions have arisen. For example, when a Chinese national and a Huawei employee were arrested in Warsaw in January 2019 on spying allegations, Beijing did not react with hostage diplomacy as it had with Canada.6 Yet, Chinese media published a series of articles highly critical of Poland, portraying Warsaw as a “US tool” and denying its agency.7 Liu Guangyuan, who served as China’s ambassador to Poland from 2018 to 2021, was a “moderate wolf warrior”: His diplomatic style focused more on highlighting the alleged benefits of Sino-Polish cooperation while “correcting false perceptions of China”8 in a relatively moderate fashion. Liu’s posture has seemingly worked well for him, as he was recently promoted to new commissioner of the Chinese Foreign Ministry in Hong Kong.9

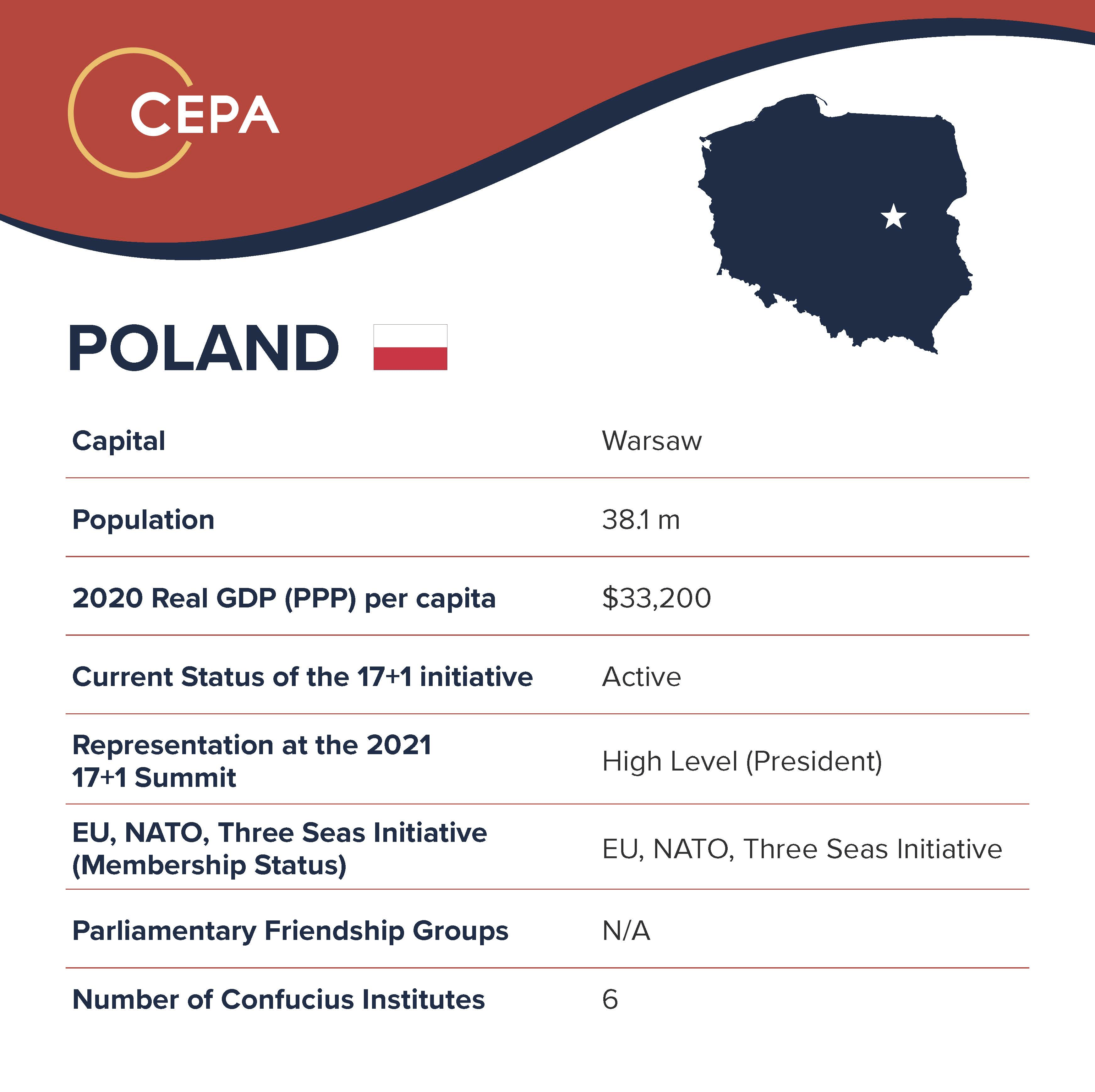

Sources: The World Factbook 2022, (Washington, DC: Central Intelligence Agency, 2020), https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/; World Bank, The World Bank Group, 2022, https://www.worldbank.org/en/home; “Polish-Chinese Parliamentary Group,” Sejm of the Republic of Poland, Retrieved June 21, 2022, https://www.sejm.gov.pl/SQL2.nsf/skladgr?OpenAgent&392&PL

Reach of influence measures

As mentioned before, attempting to establish local CCP-friendly proxies and shaping the local debate on China by promoting Beijing’s official messaging have been the most evident areas of visible Chinese influence, albeit to a limited extent, in Poland. The former was especially in play around 2012 to 2017, when the 16/17+1 platform was developing rapidly and representatives of political parties and nongovernmental organizations traveled to China repeatedly for networking and official exchanges.10 The latter has unfolded steadily over the years, but during the pandemic, China’s efforts to burnish its public image have accelerated fast. They’ve also taken on a sharper edge, as in an extended exchange of op-eds and tweets between then-Ambassador Liu and his American counterpart, former US Ambassador Georgette Mosbacher, in the first half of 2020.

Despite considerable efforts by Chinese representatives in Poland, these image-building attempts have had only mixed success. In a recent survey, 41.5% of respondents said they had a negative opinion of China, and 31.7% positive.11 Almost half of the respondents have also changed their views of China in the past three years, with 34% declaring a worsened attitude. China is increasingly seen in Poland as a source of threat, although its perceived economic potential still seems attractive to many.

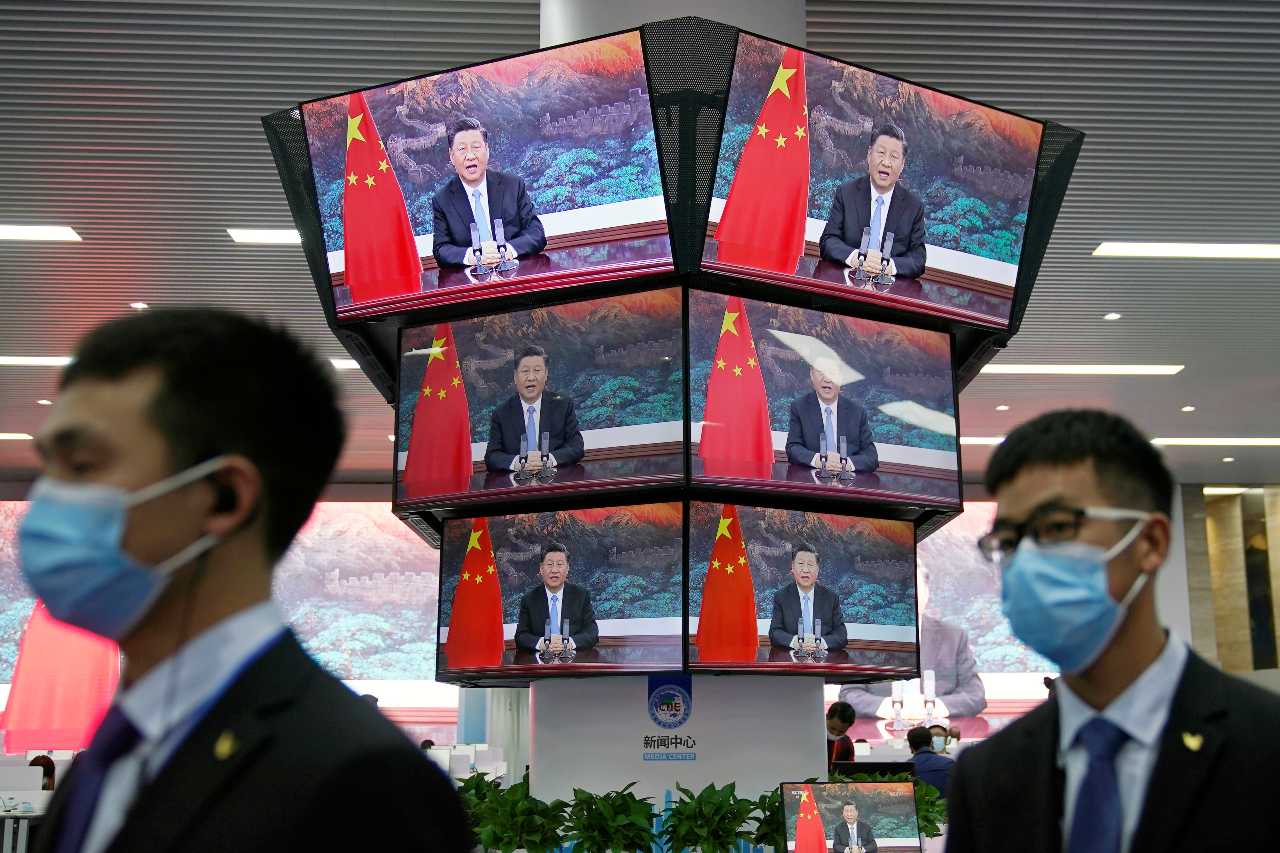

Photo: Chinese President Xi Jinping (L) and his Polish counterpart Andrzej Duda attend the signing of a cooperation treaty between China and Poland at the Presidential Palace in Warsaw, Poland June 20, 2016. Credit: Agencja Gazeta/Slawomir Kaminski/via REUTERS

Target audiences and populations

When it comes to political elites, previous studies suggest a good deal of perceived opportunism and ambivalence toward China.12 Both the ruling Law and Justice party, as well as Civic Platform and smaller opposition parties, have historically displayed interest in close cooperation with China: the Sino-Polish strategic partnership was signed during the Civic Platform’s rule, while its elevation to comprehensive strategic partnership happened when Law and Justice took power. Also, internally, political parties and their members do not have homogenous views on China. For example, some in the center-left political alliance Lewica (The Left) have almost contradictory interpretations of Beijing’s behavior: While Andrzej Szejna, a member of parliament, appeared in Chinese media to praise Xi Jinping’s handling of protests in Hong Kong,13 other members of the alliance publicly defended the protesters and supported their political demands.14

Moreover, some previous research points toward the Polish alt-right’s interests in China’s centralized and allegedly efficient style of top-down policymaking, which might also make this group more amenable to Beijing’s image-building efforts.15 This ambivalence suggests that China-related political subjects are often used instrumentally by Polish political elites and are rarely considered in broader terms. While personal sympathies might be genuine, they do not necessarily translate into well thought-through strategies of engagement.

Most Poles know relatively little about China, while the expert community is small for a country of approximately 40 million. Area studies are also underdeveloped in Poland, with Sinology focusing mostly on language and culture, thus limiting possibilities for interdisciplinary training, especially in strategically important domains such as emerging technologies, security, or climate change. Nevertheless, China-related education is not very dependent on funding from the Chinese government, with only six Confucius Institutes operating in a country with more than 100 public universities. Beijing’s public diplomacy efforts, however, have tapped into the growing demand for China-related knowledge, especially among the youth. Chinese government scholarships, offered by the embassy and Confucius Institutes, are an attractive offer both financially and academically, as they enable many to study in China who otherwise could not. Nevertheless, as already mentioned, being a recipient of this kind of scholarship does not directly translate into an uncritical approach toward the government in Beijing.

Conclusion

Overall, Poland’s importance for the Chinese Communist Party’s influence operations in Europe seems minimal. In the regional context, however, the country sits relatively high within China’s hierarchy of diplomatic importance because of its size, location, and close ties with the United States. The party’s footprint has indeed expanded in recent years in local media, academia, and people-to-people relations, though with relatively little payoff. In fact, China’s “discursive power” has weakened, with polls showing that Polish public opinion on China has soured. Especially given Beijing’s tacit approval for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, this downward trend seems likely to continue in the nearest future.

- “China, Poland lift ties to comprehensive strategic partnership,” The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, 2016, http://www.scio.gov.cn/32618/Document/1480977/1480977.htm [↩]

- Graeme Dobell, “Fourteen points on Australia’s icy times with China,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, April 6, 2021, https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/fourteen-points-on-australias-icy-times-with-china/ [↩]

- Michal Chabinski and Shixin Liang, “Chinese Twiplomacy in the age of Covid-19,” Echowall, 2021, https://www.echo-wall.eu/state-mind/chinese-twiplomacy-age-covid-19 [↩]

- Alicja Bachulska and Krzysztof Iwanek, “Growing Duality: Polish Opinions on China and Why They Matter,” The Diplomat, April 1, 2021, https://thediplomat.com/2021/04/growing-duality-polish-opinions-on-china-and-why-they-matter/ [↩]

- Guangyuan et al.,“Ambasador Chin: Stany Zjednoczone są światowym królem kłamstw,” Rzeczpospolita, 2021, https://www.rp.pl/gospodarka/art9190961-ambasador-chin-stany-zjednoczone-sa-swiatowym-krolem-klamstw [↩]

- James Palmer,“Another Win for China’s Hostage Diplomacy,” Foreign Policy September 28, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/09/28/meng-wanzhou-michael-kovrig-spavor-release-china-canada-huawei/ [↩]

- Qingqing Chen and Weiduo Shen, “Poland bound to be a loser if it follows the US in taking on Huawei analyst,” Global Times, January 11, 2019, https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1135469.shtml [↩]

- “Fact Check: Lies on Xinjiang-related issues versus the truth,” Embassy of the People’s Republic of China to Poland, 2021, http://www.chinaembassy.org.pl/pol/ywsz/ggwj/202102/t20210205_2482012.htm [↩]

- “Former Chinese ambassador to Poland Liu Guangyuan appointed FM’s new commissioner in HK,” Global Times, May 19, 2021, https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202105/1223854.shtml [↩]

- Ivana Karásková, Alicja Bachulska, Agnes Szunomár, and Stefan Vladisavljev, “Empty shell no more: China’s growing footprint in Central and Eastern Europe,” Prague: Association for International Affairs (AMO), April 2020, https://chinaobservers.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/CHOICE_Empty-shell-no-more.pdf. [↩]

- Adrian Brona, et al., ”Polish public opinion on China in the age of COVID-19. Desirable partner versus a source of concern,” Central European Institute of Asian Studies, 2021, https://ceias.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/PL-poll-report.pdf [↩]

- Matej Šimalčík et al., ”Perception of China among V4 Political Elites. Bratislava” Central European Institute of Asian Studies, 2019, https://ceias.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/V4-views-of-China_paper_FINAL-1.pdf [↩]

- Leonardo Górecki, “Poseł Lewicy: Podzielamy wspólne wartości z Komunistyczną Partią Chin,” MyPolitics, June 24, 2021, https://mypolitics.pl/pl/articles/posel-lewicy-podzielamy-wartosci-z-komunistyczna-partia-chin [↩]

- “Praworządność dla Hong Kongu! 願榮光歸香港!” Partia Razem, 2019, https://partiarazem.pl/2019/11/praworzadnosc-dla-hong-kongu-願榮光歸香港/ [↩]

- Bruno Surdel, “Polish alt-right: A friend of China,” Central European Institute of Asian Studies, September 7, 2019, https://ceias.eu/polish-alt-right-a-friend-of-china/ [↩]