This report is a part of #CCPinCEE, a series of reports published by the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA) analyzing Chinese influence efforts and operations across the nations of Central and Eastern Europe.

Goals and objectives of CCP malign influence

China has not had a particularly active presence in Slovakia, reflecting the two countries’ generally low-key relations. Overall, Slovakia has been on the margin of China’s foreign policy interest, just as successive Slovak governments have not made a priority of cultivating ties with China.

Since 2012, the relationship has been embedded within the 16/17+1 cooperation format, which has significantly increased contacts at various fora, but bilateral relations remain rather underdeveloped, and China has had a small footprint in Slovakia. It is a marginal investor in Slovakia, and many promised projects have not materialized, although that is set to change with the recently announced plans of the Chinese-owned Volvo to start making electric cars in eastern Slovakia.1 In trade, Slovakia’s deficit with China is not as deep as some of its neighbors’ in Central and Eastern Europe, taking into account intermediary goods, such as car parts, that are first sent to other countries for further industrial processes and then ultimately to China.2

For these reasons, Chinese policies toward Slovakia have not been particularly targeted and have mostly followed the general logic of Chinese foreign policy priorities, including protecting China’s core interests on issues such as Taiwan and Tibet; creating a positive image of China, Chinese foreign policy, and Sino-Slovak relations in the Slovak domestic discourse; and establishing links with local political and business leaders to induce China-friendly policies.3 Overall, China has not been very aggressive in its attempts to influence Slovak leaders and the public, although it has become more visible since the outbreak of the pandemic.

CCP’s methods, tools, and tactics for advancing malign influence

China has long been a rather passive presence in Slovakia, not least due to an absence of Chinese state media in the Slovak language. But, as in many countries, it has recently become more active in Slovakia.

Chinese ambassadors have regularly published op-eds on Chinese foreign policy and relations with Slovakia. Notably, Chinese diplomats have published in outlets that can be termed fringe or alternative, such as Nové Slovo, Dimenzie, Slovenské národné noviny, or Hlavné Správy.4 Most media that run content from the Chinese Embassy have limited reach, and publishing has been mostly performative, rather than aspiring to have an impact on the larger public debate. In keeping with that, the Chinese Embassy tends to post about its activities on its Chinese-language webpage, rather than publicizing them to the local audience.

But the embassy has placed pieces, including paid content, in mainstream outlets several times. For example, a leading business weekly newspaper, Trend, published an advertorial signed by the Chinese ambassador that repeated dubious claims that foreign actors had orchestrated Hong Kong protests against a bill allowing extradition to mainland China.5 Later, the newspaper reportedly rejected another piece from the embassy that contained misleading and false claims.6

The Chinese Embassy has become more willing to engage in the domestic discourse in recent years, although in a mostly reactive way. The embassy’s Facebook and Twitter accounts mostly repost content from Chinese state media and officials. Those posts have included conspiracy theories about the origin of COVID-19, linking it with the US. Among other activities, the embassy ran a series of “myth-busting” infographics on its social media designed to show that China reacted responsibly to the pandemic and to refute purported conspiracy theories about the virus’s origin.7 Even this content, though, was not original but rather came from other embassies and Chinese state media.

Considering the limited reach of the embassy’s preferred channels, Beijing can hardly peddle its line to the larger Slovak audience. Instead, the most important conduit for the Chinese viewpoint has been several China-friendly Slovak politicians, especially Ľuboš Blaha, a member of parliament from the SMER-SD (Direction-Social Democracy) party and a self-described Marxist.8 Blaha is known for frequent, calculated, and virulent attacks on his political opponents and anti-Western, pro-Russia, pro-China rhetoric.9

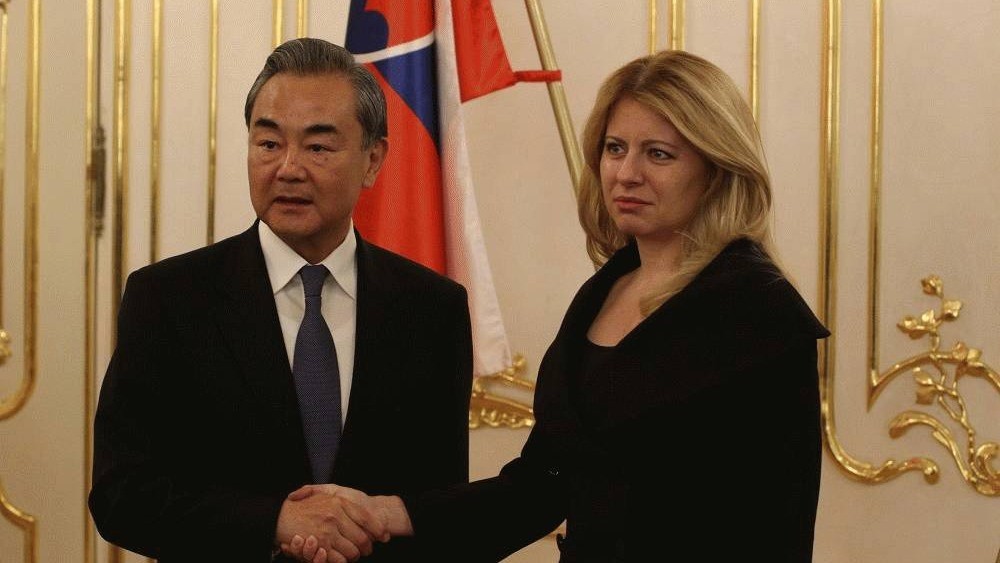

Some political attack use relations with China as a weapon against rivals. For example, opposition politicians, including former prime minister and SMER-SD leader Robert Fico, blasted President Zuzana Čaputová for criticizing China’s human rights record and her predecessor, Andrej Kiska, for lunching with the Dalai Lama. Both drew China’s ire and, their opponents said, jeopardized a valuable relationship.10 There are no reports that the Chinese Embassy made use of these pro-China statements by Slovak politicians in their own public outreach, perhaps because the embassy is wary of becoming entangled in domestic politics.

Slovakia was a target of China’s mask diplomacy in April 2020, when the prime minister and interior minister greeted a plane carrying personal protective equipment from China, an event widely promoted by Chinese media.11

Apart from China’s low profile in the public debate, Beijing has several times tried to coerce the Slovak government or other institutions. For example, during a 2009 visit of the then-president of China, Hu Jintao, a welcome party of Chinese nationals scuffled with local activists protesting human rights abuses in China. The Slovak interior minister later said the welcome party had been organized by the Chinese Embassy, despite its denials.12 Staff from the embassy and representatives of the local diaspora groups appear to have directly attacked the Slovak activists and journalists.7

The Chinese government has also pressured Slovakia to abandon several policies it sees as counter to China‘s interests. In 2021, Slovakia faced Chinese criticism for welcoming a Taiwanese delegation and for a visit by Slovakia’s deputy economy minister to Taiwan.13 Although Beijing vowed to retaliate for these actions, the countries’ economic relations appear intact. In February 2021, Slovak media reported that the Chinese government used the promise of allowing Slovak mutton exports to China to entice the Slovak prime minister to attend the 17+1 summit, where a lower-level official was originally scheduled to appear.14 Moreover, a French journalist reported that China threatened to withhold Chinese COVID-19 vaccines to Slovakia unless Slovakia sent a top-level delegation, although this was not corroborated by other sources.15

Sources: The World Factbook 2022, (Washington, DC: Central Intelligence Agency, 2020), https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/; World Bank, The World Bank Group, 2022, https://www.worldbank.org/en/home; “Friendship Parliamentary Group with the People’s Republic of China,” National Council of the Slovak Republic, Retrieved June 21, 2022, https://www.nrsr.sk/web/Default.aspx?sid=eu/sp/sp&SkupinaId=159

Reach of influence measures

In general, China has had mixed success trying to foster a positive image in Slovakia. Studies from the MapInfluenCE project find that there is more negative coverage of China than positive in Slovak media, although neutral coverage prevails.16 Public opinion can also provide insight on the perception of China, although it’s impossible to trace that directly to China’s propaganda and influence efforts.

In a survey conducted during the first wave of the pandemic in March 2020, China received high marks for its COVID diplomacy, possibly thanks to Beijing’s efforts to spotlight its aid. Sixty-seven percent of respondents said China had helped Slovakia a lot or somewhat during the crisis, compared with 22% for the EU.17 Half a year later, another poll found that people credited China and the EU roughly equally for helping Slovakia throughout the pandemic.18 In the second survey, however, 42% of respondents viewed China negatively and 28% positively, with the rest holding neutral views. A significant minority, 43%, said their view of China had changed in the past three years — 25% for the worse and 18% for the better, attesting to the fluidity of the public’s perception.

Given Chinese propaganda’s limited reach in Slovakia, opinions about China are more likely shaped by other forces, such as favorable comparisons with the West — especially as Slovaks are the least inclined among their neighbors to throw in their lot with the West.19

Beijing has also made little apparent headway in fostering China-friendly elites. Few Slovak politicians explicitly support ties with China. Past governments under SMER-SD gave lip service to a closer relationship, but even they disengaged after becoming increasingly disillusioned with actual results.20 The current government has been more vocal on topics that rankle China, including human rights, Taiwan, and the security implications of working with Huawei.

Targeted audiences and populations

Rather than winning over the public, China’s influence efforts in CEE have generally focused on building ties with political and business elites, who in turn are the primary conduit for Chinese influence because China is not an established actor in the region. The Slovak Information Service, which assesses intelligence and security threats, noted in 2020 attempts by Chinese intelligence services to build ties across the Slovak government to benefit an unnamed Chinese information and communications technology company, most likely Huawei. The SIS also reported on efforts by unspecified Chinese actors to provide prostitutes to members of parliament to build relationships.21

Political parties have not been a key conduit for China’s influence efforts, and Chinese Communist Party ties with local political parties in Slovakia are rather underdeveloped. Still, most of the key pro-China politicians have come from the SMER-SD party, which has dominated political life in Slovakia for most of the past two decades. There have been some contacts between SMER-SD and the International Liaison Department of the Communist Party.

Conclusion

In general, China maintains a limited presence in the Slovak public space and its activities remain low-profile. There have been no serious efforts by the Chinese side to significantly influence the Slovak domestic debate on China. Moreover, some politicians’ and institutions’ increased wariness of, or impatience with, China shows how unsuccessful China’s influence efforts have been. That could change, though, if the anti-establishment forces that promote anti-EU and anti-Western rhetoric get into power, as they might be more open to Chinese outreach as an alternative to the traditional orientation of Slovak foreign policy.

In summation, China has significantly extended its presence in Slovenia over the last few years. However, while Beijing’s increased economic weight has brought more opportunities to exert political clout, its influence has been relatively modest. With a relatively small media and social media presence, Chinese actors have steered away from overtly aggressive diplomacy and have treaded softly. Chinese pressure usually becomes obvious only when Beijing pushes back on specific issues it sees as harmful to China’s national image and interests. The Chinese acquisition of Gorenje is increasingly seen as a success story, and Huawei has managed to capture the Slovenian market and to win the trust of key decision-makers. At the same time, fear of China’s economic retaliation has discouraged a more united political front in support of Taiwan. Yet, to the surprise of many, Chinese ambitions to invest in Slovenia’s strategic infrastructure have been watered down. Evidently, the Slovenian government has in general put political considerations over China’s economic appeal, which will in any event continue to serve as the main axis in Slovenia’s overall China policy orientation.

- Filip Šebok, “No Belt No Road- Slovakia on the margins of China’s BRI initiative,” CEIAS, April 3, 2019, https://ceias.eu/no-belt-no-road-slovakia-on-the-margins-of-chinas-bri-initiative/ [↩]

- Klára Dubravčíková et al, “Prospects for Developing the V4+ China Cooperation Platform,” CEIAS, 2019, https://ceias.eu/prospects-for-developing-the-v4-china-cooperation-platform/ [↩]

- Karásková et al, “China’s Sticks and Carrots in Central Europe: The Logic and Power of Chinese Influence,” MapInfluence, June 23, 2020, https://mapinfluence.eu/en/chinas-sticks-and-carrots-in-central-europe-the-logic-and-power-of-chinese-influence/ [↩]

- Filip Šebok, ”Czechia: A Case Study of China’s Changing Overseas Propaganda Efforts,“ The Diplomat, April 30, 2021, https://thediplomat.com/2021/04/czechia-a-case-study-of-chinas-changing-overseas-propaganda-efforts/ [↩]

- Matej Šimalčík, “Ako slovenské médiá uverejnili čínsku propagandu,” CEIAS, August 27, 2020, https://ceias.eu/sk/ako-slovenske-media-uverejnili-cinsku-propagandu/ [↩]

- Matej Šimalčík, “COVID-19 and China’s changing propaganda tactics in Slovakia,” DigiCom, June 14, 2020, https://digicomnet.medium.com/covid-19-and-chinas-changing-propaganda-tactics-in-slovakia-cf03fadafc34 [↩]

- Ibid. [↩] [↩]

- “Skutočná sila Blahu na Facebooku: Analýza ukazuje, v čom prekonáva ostatných politikov,” TASR, August 2, 2021, https://slovensko.hnonline.sk/6425902-skutocna-sila-blahu-na-facebooku-analyza-ukazuje-v-com-prekonava-ostatnych-politikov [↩]

- Filip Šebok, “The Curious Case of the China-Loving Slovak Parliamentarian Ľuboš Blaha,” China Observers in Cetnral and Eastern Europe, August 26, 2019, https://chinaobservers.eu/the-curious-case-of-the-china-loving-slovak-parliamentarian-lubos-blaha/ [↩]

- “Fico kritizoval Kisku za jeho vyjadrenia na adresu V4,” SITA, October 20, 2016, https://spravy.pravda.sk/domace/clanok/408565-fico-kritizoval-kisku-za-jeho-vyjadrenia-na-adresu-v4/; Katarína Filová, Eva Štenclová, “Danko chce ‘vyžehliť’ Čaputovej kritiku Číny,” Pravda, August 12, 2019, https://spravy.pravda.sk/domace/clanok/522225-danko-chce-vyzehlit-caputovej-kritiku-ciny/ [↩]

- “Aircraft with Face Masks from China Lands at Bratislava Airport,” TASR, March 19, 2020, https://www.tasr.sk/tasr-clanok/TASR:20200319TBA02084 [↩]

- Gabriela Pleschová and Rudolf Fuerst, “Mobilizing overseas Chinese to back up Chinese diplomacy: the case of president Hu Jintao’s visit to Slovakia in 2009,” Problems of Post-Communism , 2015. [↩]

- “Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Wang Wenbin’s Regular Press Conference,” Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, October 22, 2021, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/xwfw_665399/s2510_665401/t1916229.shtml [↩]

- “Čína konečne povolí dovoz ovčieho a kozieho mäsa zo Slovenska,” Pravda, February 9, 2021, https://ekonomika.pravda.sk/krajina/clanok/577445-cina-konecne-povoli-dovoz-ovcieho-a-kozieho-masa-zo-slovenska// [↩]

- Sylvie Kauffmann, “After the interview, Bratislava came under intense pressure from Beijing to rescind its decision,“ Twitter, February 10, 2021, https://twitter.com/SylvieKauffmann/status/1359593305265299461 [↩]

- Karásková et al, “Central Europe for sale: The politics of China’s influence” , MapInfluence, 2018, https://mapinfluence.eu/en/central-europe-for-sale-the-politics-of-chinas-influence-2/, https://mapinfluence.eu/en/paper-careful-or-careless/ [↩]

- Vladimír Šnídl, “Fakty vs. dojmy: Ako Slovensku reálne pomáhajú Rusko, Čína a Európska únia,” Denník N, April 4, 2021, https://dennikn.sk/1830536/fakty-vs-dojmy-ako-slovensku-realne-pomahaju-rusko-cina-a-europska-unia/ [↩]

- Matej Šimalčík et al., “Slovak public opinion on China in the age of COVID-19,” Central European Institute of Asian Studies, 2020, https://ceias.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/SK-poll-report_FINAL.pdf [↩]

- Hajdu et al., “Central and Eastern Europe one year into the pandemic,” GLOBSEC, 2021, https://www.globsec.org/publications/globsec-trends-2021/ [↩]

- Richard Q. Turcsányi, “Fico pre rozvoj vzťahov s Čínou neurobil prakticky nič,“ Denník N, November 7, 2016, https://dennikn.sk/602336/fico-pre-rozvoj-vztahov-s-cinou-neurobil-prakticky-nic/ [↩]

- “Správa o činnosti SIS za rok 2019,“ Slovak Intelligence Service, September 2020, https://www.sis.gov.sk/pre-vas/sprava-o-cinnosti.html; Tomáš Kyseľ, “Číňania mali našim poslancom platiť prostitútky. Mohlo sa to stať, pripúšťajú niektorí,” Aktuality.sk, December 2, 2020, https://www.aktuality.sk/clanok/844582/cinania-mali-nasim-poslancom-platit-prostitutky-mohlo-sa-to-stat-pripustaju-niektori/ [↩]