During the last 70 years, democracies have tried to co-exist with tyranny, and yet this cynical, unrealistic wish will never be reciprocated. The Communist Party of China’s (CCP) culture of power is captured succinctly in its own words, “You die, I live,” (你死我活.) There is no such thing as “healthy competition” with opponents who are plotting our demise, and Biden administration officials who think otherwise are in for a rude awakening.

The West’s attempts to live in peace with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) have continued even as it has shifted from a closed tyranny under Mao Zedong to an open tyranny under Deng Xiaoping, who ruled from 1979-1997.

As a closed tyranny, Mao could hurt only his own people, but he did so on a historic and unprecedented scale in his years of power from 1949-1976. Estimates of the dead under Mao range wildly — between 60 million to 140 million (The Black Book of Communism, published by Harvard University Press in 1999, offers a conservative estimate). Even at the low end, Mao killed more Chinese people than all of China’s previous invaders combined; and that includes the Mongols, the Manchus, and the Japanese with their modern weapons of mass destruction. Simply put, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) regime has been a colossal and unmitigated calamity for the Chinese people.

The world chose not to notice.

Instead, President Charles de Gaulle of France established diplomatic relations with China in January 1964, while China was experiencing the greatest man-made famine in history; President Richard Nixon conferred legitimacy on Mao with his February 1972 visit to China, in the midst of the Cultural Revolution, at a time when Mao had little legitimacy left with the Chinese people; and President Jimmy Carter “normalized” relations with the PRC in 1980.

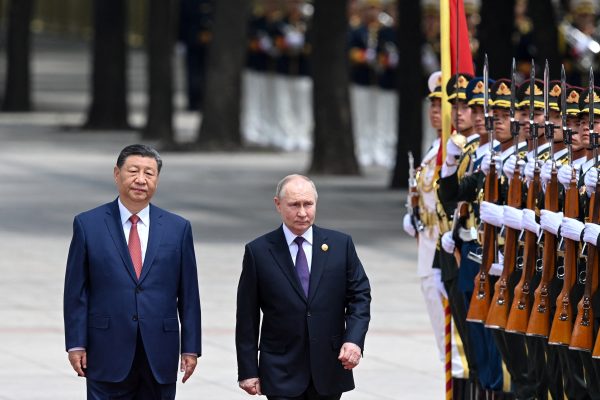

Overlooking the calamity of the Chinese people has led the world’s democracies to their most egregious strategic error. By granting Permanent Normal Trade Relations (PNTR) in 1999, and admission into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, free societies opened their markets and rescued the CCP from its disastrous economic policies. The size of the Chinese market, the coerced low labor costs, and the lure of profits have enabled Deng and his successors Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao, and now Xi Jinping, to expand the CCP’s open tyranny and develop enormous economic and military strength. The democracies “fed the crocodile,” to paraphrase Winston Churchill, and now it is big, strong, and very hungry.

The CCP tyranny is a grave danger; it is unlikely that if it were to gain power over the world’s democracies, it would treat the world better than its own people. A casual observation of the CCP’s activities around the globe would expose the lie to the often-invoked assertion that the ambition of the CCP party state will be satisfied with Asia as its own backyard.

In the contest of values, one would think democracy should win hands down. Yet this is not happening. Why?

There have been three stages to the United States’ human rights approach toward China, none effective:

- Denial of human rights, up to 1989: “the Realist school,” which has dominated many universities and governments, emphasizes interests and has argued that the “Chinese don’t care about human rights.” It is undeniably true that the CCP elite don’t care about the human rights of their people, but demonstrably untrue of the CCP’s legions of victims. This is not complicated — just ask any victim if they would like their abuse to stop.

- Severing the link between human rights and trade, from 1993 onward; this marked a resort to compartmentalization, a strategic sleight of hand that works only if opponents follow the same rules, which the CCP regime does not. Compartmentalizing values from trade has subverted both those values and free trade. America’s manufacturing sectors have been devastated, along with many small towns that were once the bulwark of American democracy. Most of America’s small- and medium-size companies are shut out of the China market. Only select corporations, which must demonstrate repeatedly their eagerness to do the CCP’s bidding (and to have their proprietary secrets looted,) have been allowed to make money through trade. Qin Hui, the renowned Chinese essayist, wrote that what the PRC offers is not just lower labor costs, but human rights abuses designed to depress workers’ incomes. The uncovering of huge concentration camps in Xinjiang is currently exhibit number one. Paying lip service to human rights while enabling the abusers is not only hypocritical, it is self-defeating; because this will lead to democracy’s decline, and if not corrected in time, to its demise.

- Minor sanctions (the current phase) is a much-needed improvement; but the CCP party state can swat away small-scale measures. It is worth noting that the hubris of CCP elite is such that they often overreact; thus making minor sanctions work better than they have any reason to.

To be effective, democracies’ human rights sanctions need to aim at the jugular, and they need to be coordinated. Moreover, if the West and its allies aim to win without a hot war, we need the Chinese people — only they have the numbers to overwhelm the guns. The current focus on China’s peripheral areas defeats this aim. There simply aren’t sufficient numbers in the peripheral areas to threaten the monolithic state — from a population of 1.47bn, there are only some 6m Tibetans, 11m Uyghurs, 7m Hong Kongers and (beyond its current borders) 24m Taiwanese. Even adding the Inner Mongolians at 5m, the total is still less than 5% of China’s total population. China is demographically very different to the Soviet Union, where ethnicities from captive nations comprised more than half the population, enabling ethnicities to become an effective splintering force.

The West may have lost confidence in the idea, but universal human rights represent a continuing allure for many of the world’s oppressed peoples, and this is therefore where democracies can win the argument. The promise of a better future, where individuals are respected and valued, appeals to the Chinese people the same way it appeals to Americans. Victims are desperate for protection. Yet democracies have seldom been there for them. Democracy is simply not worth its salt if it is not effective in protecting human rights.

The contest of values is not only strategic, it is an area where democracy can and should win overwhelmingly.

Dimon Liu was born in China and fled at the outset of the Cultural Revolution. An independent commentator, she has written for the Asian Wall Street Journal and numerous other publications.