Slovakia marked 20 years of full membership in NATO in March. It was not much of a party.

Instead, the anniversary saw the country’s allies starting to treat their notional partner much as they do its neighbor, Hungary — as a potential weak spot in the alliance.

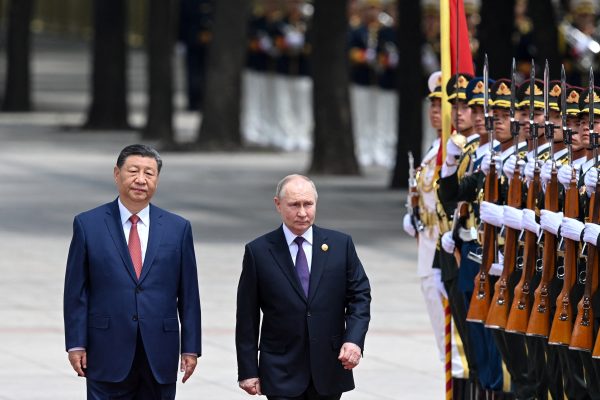

Following an election in autumn last year, narrowly won by a populist-nationalist coalition, the new Slovak government has veered in a markedly Russia-friendly direction.

A series of moves, most notably a cordial meeting between the Russian and Slovak foreign ministers in March, prompted the Czech Republic, traditionally Slovakia’s closest ally, to downgrade relations.

More recently, the local media, citing unnamed Czech and NATO officials, have reported that Slovakia’s Western partners are no longer sharing sensitive documents and intelligence with Slovak counterparts.

It doesn’t help that Slovakia’s various intelligence agencies have long struggled to generate much confidence among their Western partners. In part, this stems from an unfortunate reputation they have acquired for prioritizing the acquisition of political kompromat over the protection of national or alliance interests.

The main intelligence agency, the Slovak Information Service (SIS), which handles domestic and foreign espionage, became politicized almost from the moment of its creation, soon after independence in 1993. Its reputation is still scarred by scandals in the 1990s when it acted under the Kremlin-friendly prime minister Vladimír Mečiar and was widely believed to have been behind the kidnapping of the then-president’s son. Mečiar denies any involvement.

The subsequent cover-up involved the murder of a police go-between; the SIS’s then-chief, Ivan Lexa, fled to South Africa and was later extradited. Subsequent criminal cases against him were stymied by amnesties issued by Mečiar.

Later SIS leaders have enjoyed considerably higher public profiles than one might expect for people in their line of work.

Take the current de facto chief of the SIS, Pavol Gašpar. He was installed via a legal workaround after President Zuzana Čaputová, who should technically appoint the agency’s director, expressed doubts about his thin resumé. Reports about his unexplained wealth and previous threats to kill a prosecutor did not help.

In Slovakia, Gašpar is known mainly for an elaborate tattoo on his forearm depicting his father, Tibor, a controversial former police chief who, since being elected as an MP for the governing Smer party in September, steered through parliament a law change that will drastically reduce statutes of limitations and sentences in public-sector corruption cases. Coincidentally, Gašpar Sr is himself currently facing serious criminal charges.

He also sits on the parliamentary committee seeking to hold the intelligence services — most notably the one now being run by his son — to account. Father and son declare that their relationship will not affect their duties.

Two previous leaders of the SIS also currently stand accused of corruption and alleged attempts to interfere in high-profile police investigations.

One, released from detention in 2021 after the country’s chief prosecutor canceled the charges against him for still-unclarified reasons (he has since been charged again), was memorably driven away from the prison gates in an ultra-expensive, bright orange sports car.

Meanwhile, the current head of the National Security Office (NBÚ), which deals with securing classified information, is facing charges of abuse of office. He, along with both the accused former SIS chiefs, is known to be a close associate of Peter Košč, a businessman and former head of counterintelligence at SIS, who has long been credited with influence on Slovak intelligence operations and appointments. Košč is currently the subject of an international arrest warrant and is reported to be in Africa or, more recently, Canada.

Slovakia’s military intelligence arm is not in a much happier place. Two of its former chiefs were charged in the fall with malfeasance related to procurement. They deny the charges – as do all those named in this story. (Most of the cases detailed here have become bogged down in legal-political maneuvers on their way through Slovakia’s sluggish justice system.)

The military intelligence agency has enjoyed some notable recent successes, surveilling a Russian embassy official recruiting a Slovak writer with contacts in the military. He was eventually given a suspended sentence. More seriously, investigators charged Pavel Bučka, the former vice-rector of Slovakia’s national military academy, with having been a long-term spy for Russia’s GRU military intelligence agency.

At a ministerial level, it emerged at the time of his appointment last year that the current defense minister, Robert Kaliňák, a key ally of Prime Minister Robert Fico, does not have high-level NATO security clearance. He was arrested in 2022 and charged with serious criminal offenses — since dropped on the chief prosecutor’s instructions — that may complicate any effort to rectify this. However, so leaky are Slovakia’s internal controls – Fico routinely discloses information from supposedly confidential police and intelligence files for political purposes – that it’s questionable anyway how much sensitive material allies would be willing to share with Slovak officials.

Another Smer MP, who is the prime minister’s chief adviser — and the defense minister’s nephew — recently raised eyebrows after announcing he would instruct the country’s new spy chief — he referred to Pavol Gašpar using a familiar form of his name, implying they are close — to examine the bank accounts of journalists.

Erik Kaliňák later walked back the comments, which came after suspicions arose, based on a report by the Czech BIS secret service, that he had been paid for appearing on the pro-Russian Voice of Europe website. The Prague-based portal was shut down in early April by the Czech authorities amid allegations that it was operating as a Russian government front operation. Kaliňák denies receiving any money from the website.

If one thing has spared Slovakia’s reputation over recent years, it has been its neighbors’ even more lurid transgressions. Poland, until recently, was regularly fighting with Brussels, and Hungary has, under Viktor Orbán, built its entire brand on antagonizing its notional allies. By contrast, Slovakia tended to appear relatively dependable.

But since the Ukraine war started, and especially following PiS’s election defeat last year, Poland has drawn much closer to its Western allies. Hungary’s antics continue unabated, but its lack of reliability and obvious proximity to Russia have now mostly been priced in by European decision-makers.

Somewhat improbably, Slovakia’s other neighbor, Austria, has lately provided additional diversions. The Alpine country’s normally prim image has been tainted by a series of increasingly baroque intelligence scandals attesting to widespread Russian influence there.

Although not a NATO member, a highly secret signals intelligence encryption device used by the alliance was reportedly passed to Russian intelligence from Austria, along with secure phones belonging to top government officials. A former intelligence and police official, allegedly commissioned by Wirecard fugitive and Russian asset Jan Marsalek, was arrested in early April.

As for Slovakia, recent events have marked something of a return to the past. The reason why Slovakia marked 20 years of NATO membership this year and not 25 years, like its Central European neighbors, was that Mečiar and his allies were so distrusted by the West — US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright memorably described Slovakia under Mečiar as “a black hole in the heart of Europe.”

The country has since entered all the major European clubs, like the EU and the eurozone, but is now gambling much of the hard-won trust that got it there. At the risk of self-inflicted political irrelevance and growing distance from the European mainstream, Slovakia seems to be achieving very little in terms of national political gain.

James Thomson is a columnist for The Slovak Spectator, the Bratislava-based English-language newspaper and website.

Europe’s Edge is CEPA’s online journal covering critical topics on the foreign policy docket across Europe and North America. All opinions are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the position or views of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis.