The novel Doctor Zhivago opens with a funeral and a question from passers-by about who is being buried. “The answer came, ‘Zhivago.’” Close to zhivogo, Russian for “the living one,” the author is unlikely to have chosen his hero’s name by accident.

When Boris Pasternak handed over the manuscript for Doctor Zhivago for publication abroad, he feared that he might soon be buried for flouting the Soviet system that had nearly buried alive Yuri Zhivago, his central character.

Unable to be published in Russian, the book was first printed in Italian in 1957, with an English translation following in 1958, a momentous year for cultural relations.

In that year, the US and the USSR agreed to a multifaceted exchange, and in early summer a group of US student editors toured the Soviet Union. After their return, six editors of Soviet magazines toured the United States, with me, a Russian speaker, as their guide and interpreter.

We met with Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., Adlai Stevenson, Eleanor Roosevelt, William O. Douglas, and — very briefly — Richard Nixon, then the vice president. Standing in front of the US Supreme Court, where he had sworn in an official, Nixon said to the editors, “We’re all in politics. So let’s smile for the camera.” For once I did not faithfully translate what was said.

When the editors’ interview with Eleanor Roosevelt was televised in the USSR, the Soviet producers edited and distorted her words. When I protested to the American network that set up her interview, they told me: “Sonny, don’t rock the boat. We have business to do over there too.”

I should have taken my complaint to the CIA, because — unknown to me at the time — the American part of the editors’ exchange was bankrolled by the CIA through the Foundation for Youth and Student Affairs. It would have liked Roosevelt’s liberal views to get through to Soviet viewers.

In September 1958 I arrived at Moscow State University with 16 other US graduate students for a year of research, while three other Americans went to Leningrad. Our Soviet counterparts went to Columbia or Harvard.

Unpacking my bags in a room on the fourth floor of the Moscow State University skyscraper, I found my English-language edition of Doctor Zhivago. (Another suitcase contained costumes for native American dances, which I performed around Moscow, including at an orphanage and an army camp, where many recruits, straight from a kolkhoz, showed a cosmopolitan tolerance for strange customs.)

The Khrushchev regime had been promoting “peace and friendship,” so Soviet students flocked to me and other American newcomers like bees to honey. Within a week or two, nine or 10 of them sat in my room to sample my strange concoctions (instant cocoa and smooth Tang) and stare at this book. They had heard about Doctor Zhivago but had never seen a copy.

Unlike today, few of the Russian students then knew good English, but those that did read and passed on month-old copies of American newspapers sent to me by sea. Many also enjoyed my music lending library, with recordings by Stan Kenton and Ella Fitzgerald.

Their interest was not without risk. Having trusted excessively in the Kremlin’s words about “peace and friendship,” three of my Soviet friends were later expelled from the university for associating with me.

Deciding it was better done poorly than not at all, I did my best to render passages of Zhivago back into Russian. For example, the relationship between Yuri and Lara, the frozen beauty of their Siberian homestead, and Pasternak’s depictions of the Bolshevik regime’s inhumanity.

We sat together for an hour or so on eight or nine occasions, with some students trading places with others. I could not capture the author’s style or the evolution of his story across 600 pages, but I gave them a taste.

The book was a sensation outside the USSR but it could not be considered for the Nobel Prize for Literature unless published in its original language. Days before the committee had to decide on the prize, it received a copy of Doktor Zhivago in Russian — printed by the CIA.

In October, two days after hearing he had won, Pasternak sent a telegram to the Swedish Academy: “Immensely thankful, touched, proud, astonished, abashed.” Four days later he followed it with another: “Considering the meaning this award has been given in the society to which I belong, I must refuse it.”

Few of Pasternak’s critics had read the proscribed novel, but officials in the Writers’ Union demanded his expulsion from the USSR: “Kick the pig out of our kitchen garden,” they said. Some Russians bragged, or perhaps joked: “I did not read Pasternak but I condemn him.”

Once my listeners had been exposed to Pasternak’s feelings about the Soviet system, I asked several of them privately if the Soviet authorities were right to force him to reject the prize. Most said yes.

These Moscow University students, la crème of Soviet youth, were curious about Pasternak but agreed he should be repressed. Their affinity for Louis Armstrong and John Steinbeck did not guarantee support for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

I also learned that few Russians seemed to root for an underdog.

A decade later, I got a similar shock when I found that some of my long-time Moscow friends backed the Soviet repression of Alexander Dubcek and the Prague Spring.

I was also shocked to find that most Russian intellectuals I met in Boston years afterward backed Vladimir Putin’s brutal use of military force to crush the Chechen rebels. “Why do the Chechens kill our young men?” asked one professor visiting Boston from Siberia.

Taking the opposite view, I wrote in 2002 that Putin should be brought before the International Criminal Court for genocide.

Pasternak died in 1960 and it was not until 1989 that his son Yevgeny picked up his Nobel medal in Stockholm. At the ceremony, acclaimed cellist Mstislav Rostropovich performed in honor of his deceased countryman.

Despite or because of its ugly ways, the Soviet system brought forth giants; Putin’s adaptation of the system produced mainly pygmies.

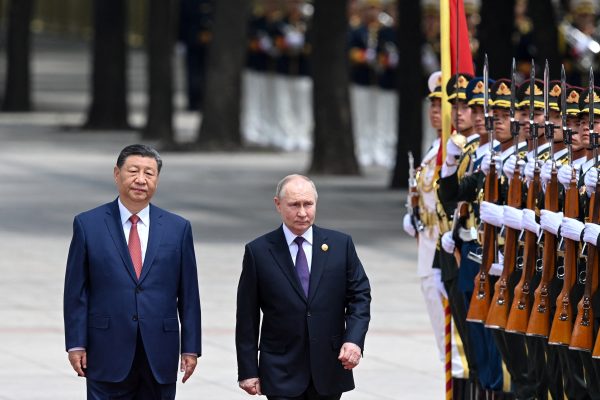

Walter Clemens is an Associate at Harvard University Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies and Professor Emeritus of Political Science at Boston University. His latest book is ‘Blood Debts: What Putin and Xi Owe Their Victims’ (Westphalia, July 2023).

Europe’s Edge is CEPA’s online journal covering critical topics on the foreign policy docket across Europe and North America. All opinions are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the position or views of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis.