Russia’s government has introduced a program to lure back Russians living abroad. According to a document issued in September, the authorities plan to return to the homeland a minimum of 500,000 fellow countrymen by 2030, promising to pay their travel expenses from the federal budget.

While a similar program has existed for 15 years, officials began to acknowledge in 2017 that the system was over-complicated. More recently, similar declarations have been heard from the general editor of RT, Margarita Simonyan, making it clear that the primary “virtue” of those wishing to return to Russia is their loyalty to the Russian authorities and their willingness to actively “work for the Russian world.” And in case there was any doubt about the Kremlin’s interest, on October 21 President Vladimir Putin confirmed that legislation granting citizenship to compatriots “must be more liberal.” It seems that this was not only a policy statement. During the past week, a number of Russian regions from Omsk to Dagestan have begun to post news on the implementation of the resettlement program.

Meanwhile, rising numbers of Russian citizens are leaving the country. An Atlantic Council report termed this phenomenon the “Putin exodus.” According to 2017 data, researchers found that nearly two million Russians moved to Western countries during Putin’s period in office. And many more would like to leave — according to opinion polls conducted by the Levada Center this summer, every fifth resident of Russia (22%) would like to move abroad, a 7% increase from 2017. At the same time, almost half of young people under 24 (48%) expressed a desire to emigrate.

Yet the Kremlin is not concerned; indeed, this is its policy goal. A new wave of repression against the supporters of Alexei Navalny, the opposition media, and human rights groups is, in fact, forcing the most politically engaged (and often most highly educated) into emigration. The choice — as with Navalny — is to depart or face criminal prosecution or even murder by the state. For Kremlin officials and propagandists, the aim is to replace disloyal Russians with pro-regime returnees.

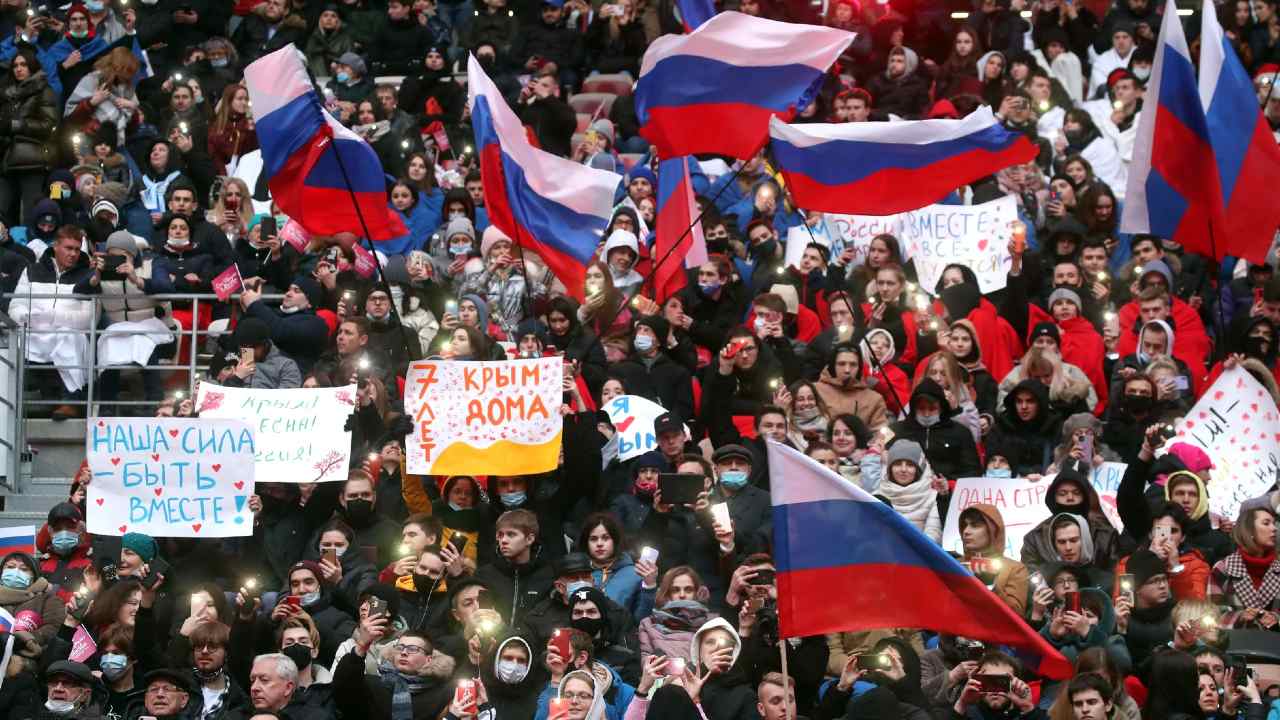

The authorities devote significant administrative energy to such projects. These extend to more widespread campaigns of both ethnic and political cleansing. It is worth noting that a similar practice has been used by the Russian authorities in occupied Crimea and Donbas. In 2017, Crimean Tatar activist Zair Smedlyaev noted that the population of the Crimean Peninsula was deliberately being displaced by newcomers. He suggested this extended beyond military and intelligence officers, to judges, farmers, officials, doctors, and educational staff. According to the leader of the Crimean Tatars, Mustafa Dzhemilev, in the three and a half years after the 2014 annexation, some 550,000 Russians and refugees from the Donbas moved to the peninsula. The problem of the displaced population of Crimea has often been raised in Geneva in various UN committees.

The policy of settling loyal Russians in occupied territory is also employed in the Donbas. According to residents, people have experienced widespread dismissals, forcing them to seek work in Russia. While some make it to Ukraine, the Russians try to prevent them from heading westwards. In their place are newcomers from distant Siberian villages who dreamed of moving to a big city (and whose unfamiliarity with the urban environment is so great that their children are fascinated by paving slabs and store signs).

This approach serves a double purpose; Russia can control the occupied territories and also select those Ukrainians loyal to the Kremlin. This was one of the goals of the spring 2019 decree simplifying the procedure for Donbas residents to acquire Russian passports. Now the Russian authorities seem to have decided to apply this technique throughout the country.

It won’t work, however. Attempts to replace the opposition with bussed-in patriots are doomed to fail for several reasons. First, popular dissatisfaction in Russia is growing, and opposition sentiment is increasingly taking on a pro-Soviet, communist tint. Such people have no favorable opinion of the West and are not inclined to leave the country, yet still are becoming less loyal to the Russian authorities.

Secondly, those returning to the “Russian world” require significant financial support. At the same time, the Minister of Economic Development, Maxim Reshetnikov, stated that the economic recovery had petered out and that growth next year will fall. Russia will gain from a higher oil price, but funds are clearly limited. Third, even the most avidly pro-Russian people currently living in the West have become accustomed to a high standard of living and the benefits of government constrained by the rule of law. They may quickly become disillusioned with the “Russian world” once they are reminded of its realities.

And things are not going well in occupied Ukraine. The indigenous population can be removed but experts note that even residents of Crimea, who were previously loyal to the Russian president, are starting to become disillusioned — last winter, the authorities had to ration fresh water, while local people have sourly noted that luxury sanitoriums in large and pleasantly wooded grounds have been handed over to Russian prosecutors, the FSB secret police and Putin’s presidential office, for notional sums. This may help to explain why supposedly loyalist Crimea saw an unexpectedly strong turnout to support Navalny in January.

Also, the repression of the indigenous population of Crimea and Donbas entails painful legal consequences for Russia. As noted by the former Vice President of the Parliamentary Assembly of the European Council, Georgiy Logvinskiy, the Crimean Platform summit held in August returned the issue of the occupation to the international agenda, which opens up the possibility of developing new ways to influence the aggressor country, including the creation of international tribunals, the freezing of foreign assets of Russian officials, and so on. All this makes the policy of squeezing out the indigenous population much more costly.

Kseniya Kirillova is an analyst focused on Russian society, mentality, propaganda, and foreign policy. Author of numerous articles for the Jamestown Foundation, Kirillova also wrote for the Atlantic Council, Stratfor, and others.

Europe’s Edge is an online journal covering crucial topics in the transatlantic policy debate. All opinions are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the position or views of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis.