Executive Summary

Since Russia began its full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, hundreds of thousands of Russians — if not more than a million — have fled the country. Activists, journalists, intellectuals, businesspersons, and software engineers have sought a combination of freedom, safety, and prosperity outside their country’s borders, often at significant material risk to themselves and their families. Many have little hope of ever going back. The war and the exodus of the Russians has deeply affected the existing émigré organizations: anti-Kremlin, launched by previous generations of émigrés, people who had emigrated for political reasons, but also pro-Kremlin, which operate under the Russian government-sponsored Russkiy Mir (Russian World) umbrella. The exodus also led to the emergence of new émigré organizations.

Western governments lack both a thorough understanding of the new Russian diaspora and a coherent policy to engage with it, secure it, and ensure that it helps contribute to a better future for the West, for Ukraine, and for Russia itself. While in exile, many Russian émigrés remain politically active, engaging with social media, assisting Ukrainian refugees, and participating in other social projects. If properly supported, these émigrés could play a crucial role in reaching out to and eventually influencing Russians within Russia. With smart Western policies of visa support, engagement, and investment, these diaspora communities could become a significant asset in the West’s attempt to contain an increasingly autocratic and belligerent Russia. Absent such support, however, these communities risk becoming a source of vulnerability or outright hostility.

To help improve Western understanding of the scale and the nature of the task, CEPA Non-Resident Senior Fellows Andrei Soldatov and Irina Borogan have delved into the landscape of Russia’s new political diaspora, the lessons that can be learned from the history of Cold War emigration, and the policy challenges and opportunities Western capitals are facing now. The resulting paper draws on extensive original field research and documentary evidence, building on and expanding their work in their most recent book, “The Compatriots.”1

Key conclusions and recommendations include:

- The new Russian diaspora is diverse in its reasons for emigration, social makeup, and geographical distribution. Western governments should thus take a bespoke approach to each subgroup.

- Information technology specialists represent the largest group of emigrants but are also the key target of the Kremlin’s efforts to repatriate émigrés. Urgent measures are needed to prevent them from becoming a resource for Russia’s war machine.

- The Russian government is replicating Soviet approaches to suppressing, infiltrating, and coopting Russian émigrés. Those efforts significantly intensified in the second year of the war in Ukraine. Western governments, by contrast, are not replicating their own Cold War practices to help bring these Russians into the fold.

- In addition to repressing émigrés and their families, Russian security services are actively using the diaspora as a tool of industrial espionage and sanctions evasion.

- Throughout the post-Soviet space and beyond, into Serbia and Turkey, governments are increasingly trying to coerce expatriated Russians into leaving and/or preventing them from entering and reentering in the first place.

1) The Landscape

The war in Ukraine has triggered a significant exodus of Russian émigrés, driven by concerns about the political climate in Russia and the impact — globally and personally — of Russia’s aggression. Activists, journalists, and civil society professionals have been driven out by fears for their lives and freedoms, and by the direct suppression of their activities. For liberal intelligentsia, including academics and analysts, the necessity of preserving their personal and professional ties to the West has been another motivating factor. The closing of Russia’s borders and curtailment of Western trade and investment has driven entrepreneurs and managers to leave as well. And IT specialists — perhaps the largest group of émigrés — have left to avoid military service and to continue their careers.

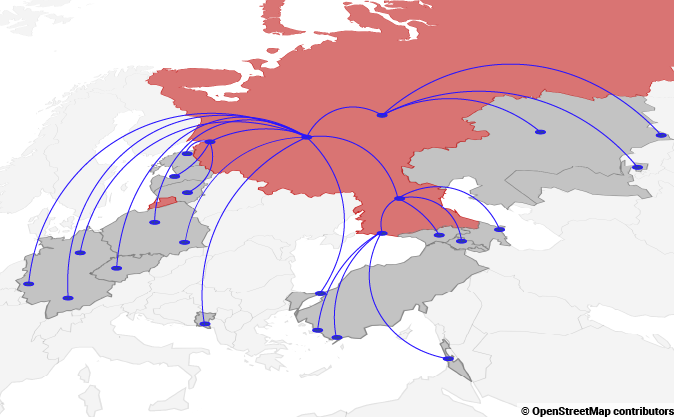

The destinations of these emigrants have varied, with many opting for countries that were formerly part of the Soviet Union, such as Armenia, Georgia, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan, due to visa constraints and financial limitations. Other popular destinations include Serbia, Montenegro, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Germany, Czechia, and Poland. Israel has facilitated the relocation of many emigrants by providing necessary documents. Dubai, in The United Arab Emirates, became another popular destination. Despite the physical distance from Russia, these political émigrés have remained active through Internet technologies, contributing to media in exile, collaborating with Russian diasporas, and engaging in political activities across different countries. The Russian government has made efforts to attract IT specialists back to Russia, offering draft deferment, financial incentives, and job opportunities related to military contracts, highlighting the strategic importance of these professionals in Russia’s defense and import-substitution efforts.

Sociology

Russia’s war in Ukraine has resulted in a huge exodus of emigrants from Russia. Hundreds of thousands of these emigrants left Russia soon after the start of the war on February 24, 2022; the majority left Russia for political reasons. People with a liberal mindset considered staying on in Russia, which started a war against its neighbor, and paying taxes to the Kremlin as immoral and potentially dangerous for them.

Russia saw five big waves of emigration before 2022: the “First Wave” left during and after the Revolution of 1917; the “Second Wave” emigrated after World War II; the “Third Wave”, left during the Cold War, the “Fourth Wave” left following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The new wave of exiles from Vladimir Putin’s Russia, which either already engaged in political activities or may have a political role at some point, can be divided into four groups.

1) Journalists, Activists, and Nongovernmental Organization Employees

This first group probably numbers around a few thousand. This group immediately understood that staying on in Russia presented an enormous risk to their freedom and life. These concerns were proven prescient when Russia’s parliament passed a law in March 2022 imposing prison time for anyone spreading “fake” news about the Russian army. Dozens of independent media organizations were blocked, some were shut down, and many journalists, as well as activists and opposition politicians, were sentenced in absentia to up to eleven years in prison.2

2) Big-City Liberal Intelligentsia

The second group is made up of professors, researchers, and historians. Many of them had ties to Western universities and were involved in projects supported by Western foundations. They could not imagine continuing their work as Russia became increasingly isolated from the West.

When these intellectuals fled Russia, they did not believe that their lives were in immediate danger. Rather, they were worried about their careers and freedom. Many professors with liberal views were fired from their universities.

3) Businesspersons and Managers of Big Corporations

The third group of exiles consists of Western-oriented businesspersons and managers of big corporations, including state-owned companies and banks. These people felt uneasy as Russia closed its borders and isolated itself from the outside world. Many of them worked for Western companies that pulled out of Russia following the start of the war, or for corporations put under Western sanctions. Among them, Dubai became one of the most popular spots.

4) Information Technology Specialists and Engineers

IT specialists and engineers make up the largest group of emigrants. According to Russia’s Ministry of Digital Development, Communications, and Mass Media, at least 100,000 such professionals left Russia in 2022.3 Before the war, many of these engineers and computer scientists were employees of US and other Western companies; others ran their own companies and did work for foreign clients. After February 24, 2022, however, it became clear that this kind of international work would no longer be possible. The sanctions imposed by the West hampered access to Western technologies, and many were unable to be paid by their Western clients or even connect to the servers of their companies.

The second wave of war-time migration of IT specialists was prompted by Putin’s September 2022 announcement of a “partial mobilization” — many of them were men in their 20s, 30s, and 40s, thus fit for the army.

Many experts do not consider this group of people to be political migrants because most IT workers left Russia out of fear of being drafted into the army, and their motives were selfish. This is a strong argument. Indeed, these people are very different from opposition politicians, activists, or independent journalists who spent years in Russia opposing the regime.

Nevertheless, we consider them part of political emigration for several reasons:

- IT specialists play an outsized role in the Russian military effort. The war in Ukraine is fought with technologies that range from drones to missiles to tanks and need IT expertise — for research, development, and production.

- IT specialists play a key role in the Russian import-substitution program. Russian IT specialists have a crucial role in this program, the main objective of which is to help the Russian economy bear the weight of Western economic sanctions.

- Thus, on what side of Russia’s borders Russian IT engineers have found themselves and on what side they are going to stay is a key political question.

- Finally, the Russian government is fully aware of the importance of IT specialists and is trying to lure those who have left the country back to Russia.

Geography

The previous waves of Russian political emigration in the 20th century ended up in Western Europe, the Balkans, Turkey, China, and later in the United States and Israel. Newer Russian emigrants chose other destinations. Most of them left for countries that used to be part of the former Soviet Union.

Armenia, Georgia, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan have taken in the most emigrants. In the first two weeks of the Ukraine war alone, Georgia took in 25,000 Russians, and Armenia was receiving some 6,000 Russians per day. By the end of March 2022, 60,000 Russians had gone to Kazakhstan.4

Their choice was defined not by their desire, but by the fact that many of them did not have visas to live and work in the European Union (EU) or the United States, or enough money to survive in Europe and the United States without work.

Serbia and Montenegro became popular destinations because those countries allow Russians to stay for a long time and get residency. Many anti-Kremlin activists and journalists moved their organizations to Lithuania and Latvia. Some political émigrés have found refuge in Estonia. Germany, Czechia, and Poland also received tens of thousands of exiles. Israel also helped many emigrants to relocate, providing them with documents.

Political émigrés — outspoken intellectuals, journalists, activists, and politicians — can be found in each and every country mentioned. Most of them have stayed active thanks to Internet technologies that, for instance, have allowed journalists resident in Yerevan to contribute to the media in exile based in Vilnius to talk to an audience in Russia and Russian diasporas all over the world.

Institutions

Putin triggered political emigration as early as 2000, forcing his opponents, ranging from oligarchs to activists to journalists, out of Russia. This process has never stopped. In the 2000s and 2010s, the new Russian exiles set up several political organizations in Europe and the United States.

At the same time, the Kremlin has been eager to spread Russian influence by setting up Russian government-sponsored organizations abroad and subordinating the existing émigré organizations.

By February 2022, the politically active Russian community abroad was well represented by all kinds of organizations — political, cultural, media, and the church.

The Church

The Russian Orthodox Church is the most significant Russian institution abroad, present in many countries in Europe and the United States. In May 2007, the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia (ROCOR), which was formed by the anti-communist White Army in exile in the 1920s, was integrated with the Russian Orthodox Church.5 This was a personal project of Putin’s from the early 2000s to subjugate the ROCOR to the Moscow Patriarchate.

Since the war began, Orthodox communities abroad have largely remained loyal to Moscow, apart from a very few priesthoods in the United Kingdom and Germany.5 A notable exception was the position of the Metropolitan Mark (Arndt) of Berlin and Germany, who openly condemned the Russian aggression in Ukraine in an interview with Hannoversche Allgemeine in June 2022.6 But he toned down his criticism of Moscow and in 2023 started echoing the arguments of the Moscow Patriarchate. For instance, in a January interview, Mark claimed that the church in Ukraine is being persecuted by Ukrainian authorities more brutally than in Germany under Adolf Hitler.7

Archbishop Gabriel of Montreal and Canada openly justified Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. “Russia was forced to take steps to protect itself from the neo-Nazis who were shelling civilians in Donbass for eight years, and continue to this day,” he claimed.8

These three prominent Orthodox officials were not born and raised in Russia, they are not commissars sent from Moscow, and their views do not appear to be enforced by Moscow. Rather, they largely reflect the orientation of Russian Orthodox communities overseas: Although many Ukrainians have defected from the Moscow Patriarchate since the invasion, many churches and parishioners in other countries have chosen to stay within the Russian Orthodox Church.

The reasons for the church’s loyalty to Moscow are mostly ideological: Many descendants of the first wave of Russian emigration remained, institutionally and personally, stuck in the memories of the glorious imperial past, which became clear after they enthusiastically supported the annexation of Crimea in 2014.9 They are naturally given to this 19th-century thinking, shared by Putin. Therefore, new, wartime Russian émigrés are largely keeping a distance from the church abroad.

The Russian Orthodox Church’s activities abroad have become a security concern in many Western countries since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. In May 2023, the FBI privately warned members of the Orthodox community in the United States that Russia was likely using the church to help recruit intelligence sources in the West.10 In September 2023, Bulgaria expelled the head of the Russian Orthodox Church in the country, Archimandrite Vassian, and two other Orthodox clerics. Bulgaria’s State Agency for National Security (DANS) said in statement that the three had worked to “purposefully influence the social and political processes in Bulgaria in favor of Russian geopolitical interests.”11

Government-Sponsored Organizations

These organizations are largely presented by entities under Rossotrudnichestvo, an umbrella body for a collection of foundations that support compatriots abroad and provide funding for Russian-language, pro-Kremlin media abroad. Their activities are coordinated with the Russian culture centers — traditionally, a cover for intelligence operations.

Since the start of invasion, many Russian cultural centers have kept a low profile, not engaging in overt pro-war propaganda. For instance, the Russian spiritual and cultural center in Paris limited itself by organizing old Soviet film screenings.12 The Russian cultural center in Belgrade focused on organizing religious festivals and concerts celebrating the Romanovs.13

Political Opposition Organizations

Russian opposition had several organizations in place beyond Russia’s borders by the time of the 2022 invasion — for example, former chess champion and political activist Garry Kasparov’s Free Russia Forum in Vilnius (founded in 2016), the largest platform of Russian opposition, and a constellation of media outlets sponsored by the exiled Kremlin opponent Mikhail Khodorkovsky (his organization has also sponsored many events across Europe). The Free Russia Foundation, launched by Russian emigrants in Washington in 2014, had branches in several countries (Free Russia Houses) active before the invasion. When the war started, most members of jailed Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny’s organization FBK (Anti-Corruption Foundation) were already abroad, fleeing oppression; they set up shop in Vilnius for their media and investigative projects.

After the invasion, a set of new organizations emerged. The Feminist Anti-War Resistance is a horizontal organization with activists abroad and in Russia. The Free Buryatia Foundation is an anti-war and anti-colonial movement that unites Buryats from all over the world. The Free Nations of Post-Russia Forum is a marginal organization that has been mostly busy exploring the idea of splitting Russia into several parts.14 And there is the Russian Democratic Club, a coalition of Russian anti-war democratic forces, launched by opposition politicians Gennady Gudkov and Dmitry Gudkov.

All these organizations increased their activities since the start of the war, focusing their efforts on two major areas:

- Organizing various events to make it possible for Russian exiles to meet up in person and coordinate their efforts,

- Engaging in all kinds of media activities, from conducting investigations into Russian war crimes and corruption to trying to keep open channels of communication with the Russians in Russia, telling them what is really going on in Ukraine and Russia. All opposition politicians came to believe that online journalism was the most important outlet, more important than street action and protests.

Journalists and Media

Meduza, launched by Russian journalists in Riga in 2014, is the most prominent Russian media organization in exile. Meduza has a unique niche — despite being in exile, it remains the most popular independent media in Russia.15

Between 2021 and 2022, more independent journalists fled Russia. They remained active when the war started. They also found a way to keep all their projects alive — from investigative websites to a TV channel, TV Rain (Dozhd, in Russian). Throughout 2022 and 2023, they have been working via online platforms like YouTube, Telegram, Facebook, TikTok, and the websites of their media organizations. Despite the Kremlin’s censorship efforts, Russian journalists in exile retain access to their millions-strong audience in Russia.

Missed Opportunities

The bulk of IT specialists and engineers who fled Russia ended up in Georgia, Armenia, and the Central Asian states. Many of them left big cities like Moscow and St. Petersburg, where they enjoyed relatively high standards of life. They did not get the same standards in the host countries. Many of them tried to relocate to Europe but failed — Western IT companies got cold feet when it came to recruiting Russians due to security and reputational concerns.

The Russian government is now trying to lure IT specialists back. The government’s strategy includes the promise of draft deferment, low mortgages, and free plane tickets to Russia, all funded by taxpayers. What makes it more attractive for the Russians is that many of those who left the country continue to work for Russian companies, albeit remotely, though the big Russian IT corporations are cracking down on remote work.

Russian IT companies launched an effort to recruit Russians in neighboring countries, for instance, in Kyrgyzstan, Serbia, and Armenia, using trade shows like Expo-Russia Kyrgyzstan in June 2022, Expo-Russia Serbia in September 2022, and Expo-Russia Armenia in October 2022, respectively.16

In July 2023, AWG, a Russian IT integrator company, claimed that approximately 85 percent of IT specialists who left Russia in 2022 had returned.17 Many of those who returned realized that the best protection against being sent to the battlefield is to work on military contracts — contributing directly to the Russian war effort.

Evidence 1 – Mikhail, a Muscovite, 32 years old

Mikhail, an IT engineer and graduate of the Moscow Aviation Institute, left Russia for Yerevan in September 2022 fleeing mobilization.

He returned to Moscow in late December because he did not like living in a tiny apartment in Yerevan. In January, he accepted a position at Skolkovo Innovation Center in Moscow as a drone developer. He got draft deferment as part of his deal.

2) The History

During the early years of the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union engaged in a covert struggle, with all-out war a very real possibility. This led to discussions in Washington about who would govern a defeated Soviet Union and how to support émigré organizations in their efforts to return to the country. George Kennan, a prominent figure at the US State Department, proposed the idea of helping émigré groups and setting up “liberation committees” to foment resistance behind the Iron Curtain. Subsequently, organizations like the American Committee for the Liberation of the Peoples of the USSR and the National Committee for a Free Europe were established. Radio stations, such as Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty, were created to target audiences in Eastern Europe and what was then the Soviet Union. Additionally, the US military set up a Russian Institute in Germany, where diplomats, military personnel, and spies were trained by Russian émigrés to gather information from behind the Iron Curtain.

On the other side, the Soviet Union had a significant counter-exile structure in place, involving various KGB directorates and departments. The Fifth Directorate focused on ideological subversion, collecting compromising material on dissidents within the country for potential use if they moved to the West. The KGB’s First Chief Directorate had units that dealt with emigrants, including spreading disinformation abroad, running external counterintelligence to prevent defections and unauthorized contacts, and planting fake news in Western émigré media. KGB stations within Soviet embassies were tasked with monitoring émigré activities in foreign countries. This complex structure coordinated efforts both inside the Soviet Union and abroad to keep tabs on and counter the activities of Soviet émigrés and dissidents — and occasionally to kill them.

Western Approaches to Soviet Émigrés

The massive exodus after the Russian revolution of 1917 took Western countries by surprise. From 1920 to the end of the Second World War, host countries apart from Czechoslovakia had no strategy towards Russian émigré communities. Prague’s strategy was focused on Russian intelligentsia. In the meantime, the Russian émigré community already had organizations like ROVS (Rossiyski Obshevoinsky Soyuz, or the Russian All-Military Union), comprising former members of the defeated White Guard. ROVS conducted operations against Bolshevik officials inside Russia and beyond the Russian borders – which made it a target for the new Bolshevik security services.

Only after the Second World War did the United States start developing a strategy towards Russian émigré groups. When the Soviet Union tested its atom bomb in August 1949, Washington quickened the pace of war preparations, calculating that within a decade the United States would become vulnerable to a Soviet attack.

Very few in the United States thought then it would be a contained regional conflict — Washington planners imagined an all-out war that would inevitably result in the collapse of the Soviet regime.

The question, then, was, who would govern a defeated Soviet Union? Washington initially took the view formulated by Kennan, then chief policy planner at the US State Department, that the US government would help all émigré organizations return to the Soviet Union to try their luck. The US government did not want to take the responsibility of “sponsoring entirely” a specific group.18

Kennan also suggested that while the Americans waited for all-out war to break out, they could concurrently begin using political refugees, organized into “liberation committees,” to foment resistance behind the Iron Curtain.

After a good deal of lobbying from Kennan, the American Committee for the Liberation for the Peoples of the USSR was launched. A second organization, the National Committee for a Free Europe, had the goal of mobilizing political exiles from Eastern Europe.

In the 1950s, Kennan’s “liberation committees” set up a few radio stations: Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty, which came to target audiences in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, respectively. The radio stations were based in the area around Munich because the postwar wave of emigration was centered in this area, a US zone of occupation. This area was also used by the CIA-sponsored operation of the NTS (National Labor Union or Narodny-Trudovoy Soyuz) of launching giant weather balloons — 20 meters in diameter, made of transparent plastic — to carry leaflets over the Iron Curtain.

The US military found a more practical use for Russian émigrés: It set up a Russian Institute in the Bavarian Alps, in the small mountain resort town of Garmisch, Germany. From the 1950s on, US diplomats, military staff, and spies about to be stationed in the Soviet Union were sent to a yearlong military training program there, conducted entirely in Russian and taught by Russian émigrés from both the first and second waves.

The United States was the only nation that had a strategy dealing with Russian émigrés. The British preferred to spend their limited funds on acquiring defectors. West Germany either passively provided its territory for the Americans to run their operations or even tried to stop them: For instance, in September 1955, the CIA ordered a temporary suspension of the propaganda ballooning to the USSR citing a “Bulganin/Adenauer discussion of leaflets allegedly launched from the German Federal Republic into the USSR.” (The Soviet government had raised an issue of balloons with West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer during his trip to Moscow, and not without result).19

Russian Approaches to Soviet Émigrés

The Soviet regime was obsessed with the threat posed by émigrés from day one of its existence: Felix Dzerzhinsky, the chief of the Soviet secret police and a founder of the Cheka, put immense pressure on his operatives to do everything in their power to undermine the exiled White Guard organizations and their allies. In March 1924, he sent his deputy a note regarding “the fight against émigré terrorist organizations.” In it, Dzerzhinsky asked if the secret service was keeping comprehensive blacklists of members of these White Guard organizations, including their relatives, in Russia and abroad.20 Under Dzerzhinsky, the country’s secret police carried out a massive and very successful false-flag operation code-named Trust to lure politically active émigrés back to the Soviet Union to help a fake anti-Bolshevik organization.

The Soviet Union’s enormous counter-exile structure looked like this at the time the KGB was at the height of its power in the 1970s and 1980s:

The KGB’s Fifth Directorate dealt with ideological subversion. It gathered compromising material on dissidents inside the Soviet Union with the goal of using this material if the dissident moved to the West.21 The Fifth Directorate also measured the impact of émigré publications in dissident circles. Its officers were assigned to Soviet artists who were traveled abroad.

Inside the Soviet Union, the KGB’s Soviet Republics departments reported on the activities of émigrés using information obtained from agents in organizations like the Society for the Development of Cultural Ties with Estonians Abroad.22

The First Chief Directorate of the KGB (Foreign Intelligence) also had several units that dealt with emigrants. Service A was in charge of spreading disinformation abroad. Its operations targeted prominent exiles — what it described as “active measures.”23 Department K ran external counterintelligence. It addressed a variety of threats to Soviet intelligence operations abroad, including preventing defections and unauthorized contacts with Russian émigrés. The Fourth Section of Department K ran agents embedded in émigré organizations, including in radio stations like Voice of America, Radio Liberty, and Radio Free Europe. These agents planted fake news in Western émigré magazines and newspapers.

In foreign countries, KGB stations within Soviet embassies — rezidenturas — had several officers who kept an eye on emigrants. These officers were attached to Line EM —“line” meaning area of operations, and “EM” meaning emigration.

Two departments in the central apparatus of the KGB helped coordinate these efforts. Inside the Soviet Union, the KGB’s Tenth Section in the Fifth Directorate (Ideology) was charged with dealing with “the centers of ideological subversion abroad.”23 The Tenth Section’s goal was to act as a contact point between all KGB units in the Soviet Union and all units at the First Chief Directorate (Foreign Intelligence) that were engaged with émigré groups.

The KGB’s Nineteenth Section within the First Chief Directorate coordinated operations outside the country. It had more than 30 intelligence officers on its staff.

These operations worked in the following manner:

In 1966, for example, Yuri Marin (Yuri Pyatakov), a Soviet sailor, jumped off a Soviet reconnaissance warship 12 miles off the coast of California and escaped to freedom.23 The US Army Russian Institute in Garmisch, Germany, which was always on the lookout for recent Soviet refugees who could provide its students (diplomats and spies) with the latest information from behind the Iron Curtain, hired Marin as an instructor. He also worked as a radio host at Radio Liberty in Munich.

It turned out Marin was a KGB agent run by the Fourth Section of Department K.23 His mission was to gather personal details about the US diplomats and spies trained in Garmisch as well as material on Radio Liberty personnel. Among the prominent US diplomats trained by Marin at the Russian Institute was Mark Palmer, later the US ambassador to Hungary, who lived for 11 years in the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia, and Hungary under the communists as a student and diplomat. Palmer was vice chairman of Freedom House and the co-founder of the National Endowment for Democracy. He recalled later that in Garmisch he was given:

“Lectures by people who were all Russians or Ukrainians or whatever. They were émigrés and had come out, many of them, after the Second World War. Some of them were quite recently defectors. And they taught everything. They taught Soviet economics, Soviet politics, Soviet military stuff…. There was one guy, Yuri Marin, who was there who had come out more recently. He’d jumped off a ship off San Francisco and swam over to another ship. He played the role of the Commie in the institute…. I don’t think anyone really knows to this day if he was planted and this whole thing was their penetration of Garmisch. Was this really a very successful KGB operation to spot all of us, to get all of our bios? We spent hours with him alone one on one. A lot of the work in Garmisch was very individual. It was wonderful to be able to do that, to spend hours talking in Russian about different aspects of Russia. So I spent a lot of time with Yuri, as did many others. He must have known everything about us for what it was worth.”24

In 1973, when Marin defected back to the Soviet Union, he publicly denounced his US hosts in Germany.22

A similar story was repeated in the 1980s when Oleg Tumanov, another Russian defector who had jumped off a Soviet ship near Libya, was hired by Radio Liberty in Munich. He fled to the Soviet Union in 1986 where, at a press conference in Moscow, he exposed the CIA’s presence at Radio Liberty.

Active Measures: From Assassinations to Targeting Relatives

The Soviet intelligence agencies responded to Western covert warfare with a string of killings abroad. Germany, and Munich in particular, became a hunting ground for Soviet secret services: In 1957, a KGB agent killed a Ukrainian émigré activist and writer with a poison vapor gun in Munich. A leader of the Ukrainian émigré community was poisoned by cyanide in 1959. An NTS chairman was about to be poisoned in 1954, but his would-be assassin defected to the West. Three years later, the defector himself barely survived a poisoning by thallium. Poison, indeed, never went out of fashion.

The Munich area was also targeted by Russian radio propaganda. One station, run from East Berlin by the Soviet Repatriation Committee, had Soviet citizens call on their husbands, sons, nephews, or old friends to return via personal letters read aloud on air. Even if the radio show did not tempt exiles to go back, it surely made emigrants think twice about taking part in any anti-Kremlin activity, in that it provided evidence that Soviet forces were keeping close watch on their relatives back home.

In the mid-1950s, this sort of blackmail tactic expanded to the United States. Countess Alexandra Tolstoy, Leo Tolstoy’s daughter, fled the Soviet Union in 1929 and in two years had moved to the United States. She lived on a farm in upstate New York and provided help to refugees coming to the United States. The countess testified to the US Senate that, in her experience, many Soviet exiles were targeted by Soviet agents. Exiles received mail “addressed to them under their original Russian names at the addresses in which they are living under false identities,” she said.25 The message was clear: The secret services had traced them in the United States, despite their new names.

3) The Challenges

Russia’s new political diaspora presents a shifting and fraught set of interlocking policy challenges for the West. At the crux of the matter is the intersection of how to harness the energies and interests of liberal-minded and pro-Western Russian émigrés, and how to counteract the strategic maneuvering of Russian intelligence agencies, who seek to harness emigration as a conduit to access the West itself.

Russian emigrants themselves, however, are beset by more than just the aggression of the Russian government and the fecklessness of the West. In many of the countries where they have sought refuge, they face suspicion and outright hostility. Wherever they land, their prospects are circumscribed as well by Ukrainian public opinion, which exercises leverage over how Western governments in particular relate to Russia and Russians. Western strategic thinking on this question is, sadly, absent.

Industrial Espionage and Penetration

Russian intelligence agencies can exploit the massive exodus of Russian IT specialists to get access to Western technologies — this objective is of strategic importance for the Kremlin’s survival under sanctions.

Evidence 1: NTC Vulkan

In March 2023, a consortium of media outlets published an investigation into Russia’s cyber capabilities based on a leak of documents from NTC Vulkan, a cybersecurity firm in Moscow that doubles as a contractor for Russian military and intelligence agencies. The leaks revealed how, for years, a group of top Russian IT engineers had been hired to work with Russian military intelligence and a research facility of the FSB [Russia’s Federal Security Service]. The leak showed that Vulkan’s engineers made a point of frequenting IT conferences around the world. Some of them left Russia and found jobs in international companies, such as Siemens and Amazon. Siemens declined to comment on individual employees but said it took such questions “very seriously.” Amazon said it implemented “strict controls,” adding that protecting customer data was its “top priority.”26

Russian intelligence agencies could use the community of political activists for penetration purposes — to infiltrate the émigré groups, and to get access to policymakers and the expert community.

Russian intelligence agencies suffered badly in 2022 due to massive expulsions from Europe. The exodus of Russians provides an opportunity for Russian spy agencies to make up for the lack of spies under traditional cover. It is a traditional method practiced by the country’s intelligence:

‘The usage of Soviet Germans by the Directorate S in the interests of Soviet intelligence.

The resettlement of citizens of the USSR of German nationality to live in the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) is essentially a stable channel for conducting intelligence work against the FRG from the territory of the USSR. Among the Germans there are many agents who had proven themselves in intelligence work in the Soviet Union were used in the interests of political intelligence. This channel is convenient for acquiring auxiliary agents (agent developers, installers, mailbox keepers) in Bonn, Cologne, Bad Godesberg, Munich, Hamburg, Bremen.

“The exit channel to the FRG is also promising for employment in target facilities. After receiving the documents of the Federal Republic of Germany and settling there, the agent can travel to other countries, where one can also hide one’s past Soviet citizenship.”

KGB defector Vassily Mitrokhin’s file of 1976, p. 79.

Physical Attacks on Émigrés

In January 2023, in an effort aimed at putting pressure on émigrés, the Kremlin started to develop a strategy to deal with the wartime wave of emigration.

Russian parliamentarians proposed measures that included the confiscation of all property in Russia and the cancellation of Russian passports. In July, a group of senators introduced a bill cancelling Russian citizenship for speaking against the war in Ukraine.27 Soviet authorities had used a similar measure against dissidents and writers like Alexander Solzhenitsyn.

Meanwhile, Dmitry Medvedev, deputy head of the Russian Security Council and a former prime minister and president of Russia, described critics of the Kremlin as “traitors who have gone over to the enemy and want their Fatherland to perish” and “scraps of s***, who until recently considered themselves to be among the so-called intellectual elite.”28

In a Telegram post, Medvedev recommended acting “according to the rules of wartime.” He cited the experience of the Great Patriotic War, as World War II is known in Russia. “In time of war there have always been special rules and quiet groups of impeccably inconspicuous people who effectively enforce them,” he wrote.29

From Medvedev’s thinly veiled threat it is clear that he was advocating the use of death squads against Russian émigrés who remain politically active.

Ever since Russia launched a full-scale war against Ukraine in February 2022, Medvedev has posted extreme diatribes on social media attacking the West, but the abovementioned Telegram post was the first time a high-level Russian official had openly called for the use of assassins to deal with critics of the Kremlin.23

There is already plenty of evidence of attacks on prominent Russian émigrés.

Evidence 1: Natalia Arno

In Prague, at the beginning of May 2023, Natalia Arno, the head of the Free Russia Foundation, suffered acute pain in her body followed by numbness.

On a plane back to the United States, her condition deteriorated to the point where she needed to visit a hospital emergency room on her arrival in Washington. The FBI and European security services investigated the case. However, the cause of Arno’s mysterious symptoms was never determined.30

Evidence 2: Dmitry Gudkov

In early July 2023, a Russian opposition politician, Dmitry Gudkov, who lives in exile in one of the EU countries, arrived at a London airport where he was taken aside by the UK police (special branch) even before crossing border control.

The UK law enforcement officers told him that his life was in danger in the UK and they could not guarantee his security. When he asked them if there was any danger to other Russian political exiles like Mikhail Khodorkovsky and Alexei Navalny’s people, they answered: Yes, they all are in danger. Gudkov noted that when he visited London 10 days earlier, everything was fine, and he was not warned about any risk to his life. He added that another activist received a similar warning in Turkey.31

Harassment in a Host Country

Sweden provides the most dramatic example to date where the Russian Anti-War Committee has come under a sophisticated attack. The attack started in December 2022 with the addition of the committee to a list of undesirable organizations by the Russian Prosecutor General’s Office.32 In August 2023, a list of committee members, which included personal data and photographs, was leaked to pro-Kremlin social media accounts.33This campaign of harassment was continued by pro-Kremlin Tsargrad TV, which republished the list of committee members.34 In September 2023, an activist, Marina Bloom, traveled to Russia and on her way back she was detained and interrogated by plainclothes officers in St. Petersburg.35 She was fined for participation in the activities of the committee in Stockholm.36

Georgia is another example. On October 12, 2023, the Russian activist Rafael Shepelev disappeared from Georgia (where he had resided since 2021) and was discovered on November 8 in a detention center in Vladikavkaz, Russia, charged with terrorism. Apparently, he was lured to the area near the border between Georgia and South Ossetia, from where he was taken by Russian operatives.37

Harassment of Relatives in Russia

During the course of the war in Ukraine, Russian security services, just like their Soviet predecessors, have turned to harassing the relatives of prominent emigrants.

Evidence 3: Marfa Smirnova

On July 24, 2023, a Russian journalist in exile, Marfa Smirnova, went public about the threats she had been receiving on social media over the past few months. Among other threats, Smirnova was sent a wiretap of her family’s apartment in Moscow, which included an audio recording of conversations within the apartment. She was also sent a photo of members of her family in a car. Up until March 2022, Smirnova was a host at TV Rain. After the channel was forced to shut down in Russia, she began working for the Insider, a Russian partner of Bellingcat.38

Host-Country Hostility

Many countries that host Russian émigrés have put in place policies that are overtly hostile toward Russians in exile.

The methods those countries’ governments have turned to include detention of émigrés at the border (usually airports); denial of entry and subsequent expulsion; extradition to Russia; harassment of émigré groups to prevent them from conducting anti-war activities, including street protests; and mysterious break-ins at apartments rented by émigrés. (See details in the table at the end of this report.)

Ukrainian Opinion

Throughout the Cold war, the world was divided between two main adversaries — the Soviet Union and the free world led by the United States. Russian political emigration operated largely between them — harassed by the former, supported and exploited by the latter.

Now, apart from the traditional state actors that affect Russian emigration, a new factor has emerged: Ukrainian public opinion in the West. Ukrainians, the primary victims of an unprovoked Russian invasion, have very strong opinions regarding Russian emigration, including its political element. These views are expressed directly and via traditional and social media — a factor unknown in the Cold War. This new factor has significantly affected Russians abroad. For instance, it has led to the cancellation of many public events with Russian participants, regardless of their position on the war.39

Western Fecklessness

The Cold War was won by the West, but not the Western Cold War approach toward Russian exiles. The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 cannot hide the fact that the Western strategy toward Russian political emigration not only failed, but backfired.

The once-legendary organizations from the first generation of Russian political emigration — the NTS, ROVS, etc. — tried to find a foothold in the rapidly changing country.40 They opened offices in post-1991 Russia, but they failed to win popular support. What is worse, under Vladimir Putin, the ROVS directly participated in the war in Eastern Ukraine in 2014 on the Russian side.41 The ROVS also openly supported Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022.42

This failure casts a very long shadow.

As result, some countries (Germany, Czechia, the Baltic states) limited themselves by dealing with a humanitarian aspect of the challenge — namely, visas for refugees.

But, overall, the lack of a coordinated effort on Russian emigrants is palpable. A top US diplomat, when asked why the United States had no such strategy, while in the Cold War there was one, insisted that there is no clash of ideology nowadays, thus no reason to promote the West as the free world, where travel was one of the essential freedoms.43

A British Foreign Office official suggested that the lack of such a strategy in the UK might be explained by the fact there is no political benefit to raising this issue in Parliament.44

At the NATO-EU level, the issue of the Russian emigrants was mentioned only by Moldova and Georgia, with regard to the security side of the problem, given the massive emigration to those countries.45

The European Parliament made an effort to gather Russia’s opposition in Brussels in June 2023. The conference, “The Day After: Brussels Dialogue. Roundtable of EU and Democratic Russia Representative,” was organized by four members of the European Parliament with some senior EU officials in attendance. The general conclusion was that the Russian opposition had failed to unite, while the idea of appointing an “ombudsman for the rights of Russians outside the Russian Federation” failed to gather any support.46

The lack of coordination and a strategy has contributed to the chaos regarding Russian émigrés or those trying to leave Russia. Within the EU, the states are divided about whether to let Russians in: While Eastern Europe has banned Russians with a Type C visa, which allows a short stay in any of the Schengen Area countries, there is no such ban in Western Europe.

Europe is also divided over the issue of Russians fleeing Russia to avoid being drafted into the army. Estonia decided to deny those Russians entry.47 In the meantime, the French National Court of Asylum ruled that Russian nationals who left Russia due to the threat of mobilization and mobilized men who refused to take part in the war with Ukraine and deserted have the right to refugee status in France. The French court referenced EU asylum law in its ruling.48

There is also no coordinated position regarding Russian media in exile. While Latvia revoked a broadcast license for TV Rain, the only independent Russian TV channel in exile, the Netherlands granted a license to the channel.49

Opportunities & Recommendations

Most Russian émigrés have remained politically active while in exile. They engage on social media; provide help to Ukrainian refugees, especially in Germany and Montenegro; and are involved in social projects. In short, they believe they are entitled to play an active role in Russian politics. That provides significant opportunities.

During the War

In Russia

Russian journalists and public intellectuals in exile continue talking to Russians in Russia, and they are listened to. The audience of Russian media in exile on YouTube and Telegram exceeds 20 million people, of whom 65% are in the country.50 This is a significant challenge to the infamous “Putin’s majority” — not all of Russia supports Vladimir Putin’s war in Ukraine. In times of crisis (and the war is the biggest crisis Putin has ever faced), Russian voices in exile, with support from those 20 million in Russia, could play a key role in eroding Putin’s support.

In Europe

Russian emigration is centuries-old, and throughout this long period it has produced large Russian diasporas in some European countries. In Germany, the Russian diaspora (especially those who moved to Germany in the late 1980s and 1990s) is strongly pro-Kremlin due to a variety of reasons, including a conflicting sense of national identity. They trust no one but the Russian voice. For many years, they have been listening to Russian propaganda.

The massive exodus of Russian journalists and media provides an opportunity for them to talk to those Russian diasporas — in Germany, but also in the Baltic states — to give them an alternative to Kremlin propaganda through a voice they could possibly trust.

Russian intellectuals in exile are an indispensable resource on expertise on Russian affairs, and many of them can contribute significantly to Russian studies in academia and the expert community.

After the War

“The reality of the Russian present has become horrible, but the Russian future appears even more bleak. Nor does the Russian past offer much hope anymore. After the Soviet Union collapsed, then president Boris Yeltsin’s narrative was straightforward and appealing: The Soviet period was a terrible deviation from a more glorious past, and Russians simply needed to regain what they had before 1917, the Russia of Leo Tolstoy, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, and Anton Chekhov. But when Putin invaded Ukraine in 2022, Russian history suddenly ceased to look so attractive.”51

It is not entirely clear what role exiles who return could play in a post-Putin Russia. But it is clear that the country will need a new national narrative, and the Russians in exile are in a position to start working on it.

Recommendations

As we describe in our book, “The Compatriots,” throughout the Soviet years, Russian political exiles never stopped trying to change the regime they had left behind. Most of these efforts had little measurable effect. It did not help that Russian émigrés were notoriously bad at building political organizations, mostly because they had conflicting views on Russia’s future once it was liberated from the communists — democrats clashed with imperialists and nationalists.

But there was one area in which Russians scored some spectacular successes: they wrote several important books that, once they were smuggled out of the country, proved instrumental in changing Western opinion about the Soviet Union. (“The Gulag Archipelago” by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, and the memoir of Svetlana Alliluyeva, Josef Stalin’s daughter, are just two examples.) And when those books were read aloud and discussed in Russian on radio stations like Radio Liberty that targeted those behind the Iron Curtain, they helped reshape public opinion within the Soviet Union itself. Other efforts were less efficacious, but these books and broadcasts worked.

These days, thanks to the Internet, Russians in exile play an even more crucial role in reaching out to Russians in Russia.

- A window of opportunity for a second (since the start of the full-scale invasion) massive wave of emigration from Russia has been shut by the Russian authorities who lost no time to tighten the rules for those eligible for military service – the opportunities to avoid being sent to the army were significantly reduced. From now on, the Russian emigration strategy in Western countries should be focused on Russians who have already left Russia.

- This strategy needs to be developed to deal with two regions:

- Countries with no visa regimes for Russians (the countries of Central Asia, Armenia, Georgia, Turkey, Serbia, and Montenegro).

- Western Europe, where recent Russian exiles have either already settled or aspire to move from the countries that do no require a visa for Russians. Unlike the previous waves of emigrants, they prefer a life in Europe to the United States.

- There is a need for the EU program to coordinate and oversee the migration of Russians who traveled to countries with no visa regime.

- A European task force that can deal with security issues created by Russian emigrants should be formed urgently. This task force should facilitate the sharing of intelligence and expertise concerning the Russian exodus.

- Russian political emigrants need to organize a public campaign that addresses Ukrainian public opinion, explaining why Russian exiles are not the enemy, but rather allies in the fight against an aggressive and totalitarian Russian regime.

- Internet connection is crucial in this war. Western democracies should ensure that the Russian media in exile can maintain its access to its audience in Russia via YouTube and social media, despite Russian efforts to censor online content.

- The Russians in exile need a space to gather and work on a new national narrative. In the second year of the war, Berlin has become the city to which more and more Russian public intellectuals, journalists, and experts are moving. Berlin appears to be the ideal location for a university and publishing house that will engage in education programs, providing expertise, and publishing projects.

- The West must admit that there is an ideological struggle underway with Russia, even though the Kremlin lacks a well-defined ideology, unlike the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc during the Cold War. In this new ideological struggle, the West should recognize that the Russians in exile have the right and duty to fight side by side with Western democracies — just like George Orwell’s “Animal Farm” was supplemented by Solzhenitsyn’s “The Gulag Archipelago.”

Many countries that host Russian émigrés have either developed policies that are overtly hostile toward Russians in exile or tolerate Russian security services’ operations targeting emigres on their soil.

Armenia

In July 2023, Irina Belacheva was detained at Zvartnots International Airport, Yerevan. Belacheva was on the Russian wanted list because in 2016 she had taken part in a protest outside the Russian Embassy in Kyiv. Ukraine granted her refugee status. Belacheva was released after a brief detention.52

Belarus

Alexei Moskalyov, whose daughter was temporarily placed in an orphanage for creating an anti-war drawing at school, was himself accused of discrediting the Russian army. He fled to Belarus but was extradited to Russia on April 12, 2023. He was given a two-year prison sentence, and his daughter was sent to an orphanage.53

Georgia

In September 2022, Mitya Aleshkovsky, a Russian journalist and media manager who relocated to Tbilisi after the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine, was denied entry to Georgia and sent to Armenia.54

Photojournalist Vasily Krestyaninov, who moved from Russia to Georgia in 2021, was deported without explanation when he attempted to fly into the country on August 23, 2023.55

On December 10, 2022, Aleksey Ponomarev, the editor of the independent Russian magazine Kholod’s podcasts, was denied entry into Georgia after flying to Tbilisi from Riga, Latvia.56

On February 13, 2023, Anna Rivina was denied entry into Georgia following a work trip to Yerevan. The Russian women’s rights activist, who lives in Georgia, was not allowed to enter the country just days after Russia declared her a “foreign agent.”57

On February 20, 2023, Filipp Dzyadko, a Russian writer and journalist, was denied entry into Georgia after returning from his travels in Europe.58

On March 5, 2023, Mikhail Fishman, a journalist at TV Rain (Dozhd in Russian), was denied entry into Georgia. The Georgian Ministry of Internal Affairs rejected claims that Fishman was barred from entering the country due to his professional background.59

On March 10, 2023, David Frenkel, an independent Russian journalist with the Mediazona website, was refused entry into Georgia.60

Kazakhstan

In December 2022, Kazakhstan deported Mikhail Zhilin, a Russian citizen and an officer with Russia’s Federal Protection Service (FSO), back to Russia. Zhilin had fled Russia’s mobilization after the start of the war in Ukraine. “[Kazakhstan’s] migration police handed [Zhilin] to the border guards and the border guards said they handed him over to Russia,” Zhilin’s wife, Yekaterina Zhilina, told Novaya Gazeta Europe. On September 26, 2023, Zhilin sought political asylum in Kazakhstan after border guards detained him for entering the country illegally.61

Kyrgyzstan

In late May 2023, Kyrgyzstan deported Russian anti-war activist and anarchist Aleksei Rozhkov back to Russia for allegedly setting a military recruitment center in the Russian town of Beryozovsky on fire in March 2022. Rozhkov had fled from Russia to Kyrgyzstan in December 2022 after Russian authorities declared arson attacks targeting military recruitment centers to be acts of terrorism.62

On June 4, 2023, Alena Krylova, a Russian activist, was detained in Kyrgyzstan. She was officially charged with helping establish an organization, whose name translates as Left Resistance, that Russian authorities deem to be extremist. Krylova fled to Kyrgyzstan even before the start of Russia’s full-scale war with Ukraine. Her detention was extended until October, 2023, with no further information about her case.63

Lev Skoryakin, a Russian left-wing activist, was wanted by Russian authorities in connection with a 2021 protest outside a building belonging to Russia’s FSB in Moscow. He settled in Bishkek where he was waiting for a political asylum decision by the German authorities. Skoryakin was detained this summer by Kyrgyz law enforcement.64 In June 2023 he was detained in Bishkek, then released in September. In October he disappeared in Bishkek. On November 3, 2023, Skoryakin was found in a Moscow detention center. In Russia, he is accused of “hooliganism”.65

Serbia

Peter Nikitin, a prominent anti-Kremlin activist, resident in Serbia since 2016, faced entry denial upon his return to Serbia on July 13, 2023. According to his legal representative, the Security Information Agency (BIA) of the country had issued a deportation order. It wasn’t until July 14, after spending more than 24 hours in the transit zone of Belgrade Nikola Tesla Airport, that Nikitin was eventually granted passage through passport control.66

On July 25, local authorities cancelled the residence permit of Vladimir Volokhonsky, one of the founding members of the Russian Democratic Society in Serbia, citing “a threat to national security.”67 Eventually, he moved to Germany.

Hungary

In mid-October 2023, a Russian anti-war activist living in exile in Budapest had her apartment broken into twice. Police claimed the motive was robbery, but nothing was taken. Days before the first incident, the manager of the apartment block had replaced the signs on the doors, adding her name, and in a few days, a black circle appeared next to her name.68

Turkey

An agreement between Russia and Turkey on Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Cases and Extradition was ratified in 2017.69 In November 2022, Russian Prosecutor General Igor Krasnov visited Ankara, where the prosecutor generals of the two countries signed a two-year cooperation program. The text of the document was not made public, but Krasnov pointedly said, “It was Turkey that became the key in Russia’s extradition procedures and transit of criminals extradited to Russia by third countries.”70

This statement worried Russian émigrés in Turkey, and those who use Turkey as a transit hub on their way to and from Europe.71

In March 2023, the Russian General Prosecutor’s Office claimed that Russia and Turkey had worked out a new method of “transporting extradited criminals via third countries.” This new method “involves transferring extradited individual from a third country to Russia via Turkiye.”72 The General Prosecutor’s Office cited a January 2023 example, when a Russian citizen who was “accused of large-scale fraud and later absconded to Romania was arrested there by the Interpol and sent to Moscow through Turkiye after Russian General Prosecutor’s Office sent an extradition request.”

However, as of July 2023, there are no known cases of Russian émigrés or exiles being extradited from Turkey to Russia.

All opinions are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the position or views of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis

- Soldatov, Andrei, and Irina Borogan. The Compatriots

The Brutal and Chaotic History of Russia’s Exiles, Émigrés, and Agents Abroad. New York: Hachette Book Group, 2019. [↩] - BBC News Русская служба. “Майкла Наки и Руслана Левиева заочно приговорили к 11 годам,” August 29, 2023. https://www.bbc.com/russian/articles/c51vgyx3dj3o. Irina Borogan and Andrei Soldatov “Escape From Moscow. The New Russian exiles —And How They Cab Defeat Putin,“ Foreign Affairs, May 13, 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/russian-federation/2022-05-13/escape-moscow. [↩]

- Bobrova, Tanya. 2022. “Head of the Ministry of Digital Development: About 100,000 IT Specialists Have Left Russia – Migration on vc.ru.” (In Russian). vc.ru, December 20. Accessed December 5, 2023 https://vc.ru/migrate/566570-glava-mincifry-iz-rossii-uehali-okolo-100-tysyach-it-specialistov. [↩]

- Irina Borogan and Andrei Soldatov “Escape From Moscow. The New Russian exiles —And How They Cab Defeat Putin,“ Foreign Affairs, May 13, 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/russian-federation/2022-05-13/escape-moscow. [↩]

- Despite the 2007 Act of Canonical Communion, the Russian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) and the ROCOR have retained separate organizations and parishes. [↩] [↩]

- Konstantinova, Elena. 2022. “Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia Published a Statement on the War in Ukraine.” (In Russian). SPZH, July 20. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://spzh.news/ru/news/89830-v-rpcz-opublikovali-zajavlenije-o-vojne-v-ukraine. [↩]

- Thoralf Cleven, “Metropolit Mark zum Krieg in der Ukraine: ,Ich traue den Bildern nicht mehr´,” Hannover Allgemeine, May 29, 2022, https://www.haz.de/politik/russisch-orthodoxe-kirche-warum-sind-gebete-munition-metropolit-mark-WHWA3PWSKBC2ZJE57NARAHHCY4.html?fbclid=IwAR2t_HCY4w8eqoF1ANUCFCNZ6v9VltmWQUss4H2KAsjlzUS8FRs18nLqEUc)

In London in March 2023, Bishop Irenei, the head of the Diocese of Great Britain and Western Europe and one of the most influential officials in the ROCOR, issued an “Open Letter on the Persecution of Christians in Ukraine” in which he cited “the tragedy of the most extraordinary and heartless persecution of Christians taking place in many parts of the country.” The letter put the blame for this persecution on Ukrainian authorities, not the Russian army: Irenei was referring to Ukrainian charges against clerics of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church who have supported the Kremlin. ((“Bishop Irenei of London and Western Europe Issues an Open Letter on the Persecution of Christians in Ukraine, and a Call for Prayer in All Churches,” Communication from the Diocesan Bishop, March 18, 2023. https://orthodox-europe.org/content/open-letter-persecution-in-ukraine/. [↩]

- Tom Blackwell. “Leader of Russian Orthodox Church in Canada Defends War on Ukraine,“ nationalpost, August 24,2022, https://nationalpost.com/news/canadian-church-leader-defends-russias-war-on-ukraine. OrthoChristian.Com. “Archbishop Gabriel (Chemodakov) of Montreal and Canada: `Canada’s decision to impose sanctions against Patriarch Kirill is absurd. The ROCOR continues to commemorate him during the services´,“ August 8, 2022, https://orthochristian.com/147606.html. [↩]

- More details see in our book The Compatriots, Chapters 24 and 35. [↩]

- Foreign Affairs, Andrei Soldatov, Irina Borogan, “Putin’s Useful Priests: The Russian Orthodox Church and the Kremlin’s Hidden Influence Campaign in the West”, September 13, 2023 https://www.foreignaffairs.com/ukraine/putins-useful-priests-russia-church-influence-campaign [↩]

- RFE/Radio Liberty, “Bulgaria expels One Russian, Two Belarusian Clerics Accused of Spying”, September 21, 2023 Foreign Affairs, Andrei Soldatov, Irina Borogan, “Putin’s Useful Priests: The Russian Orthodox Church and the Kremlin’s Hidden Influence Campaign in the West”, September 13, 2023 ((https://www.foreignaffairs.com/ukraine/putins-useful-priests-russia-church-influence-campaign [↩]

- Website of the Centre Spirituel et Culturel Orthodox Russe, Announcement of events, Centre Spirituel et Culturel Orthodox Russe, last access October 06, 2023, https://centrerusbranly.mid.ru/fr_FR/all-events. [↩]

- Russki Dom. 2023. “Concert ‘In Glory of the Tsar’s Family Romanov.’” July 18. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://ruskidom.rs/2023/07/18/31779/ [↩]

- www.freenationsrf.org. “Free Nations of Postrussia Forum.” Accessed December 5, 2023. https://www.freenationsrf.org/. [↩]

- Semrush. “Website Overview for meduza.io.” Accessed August 2023. https://www.semrush.com/website/meduza.io/overview/. [↩]

- Zarubezh-Expo, OJSC. “About.” Accessed December 5, 2023. http://eng.zarubezhexpo.ru/about/ [↩]

- Chimauchem Nwosu. “Russia’s IT Brain Gain: Professionals Return Home, Reversing Long-Time Trend,“ Sputnik International, July 10, 2023, https://sputnikglobe.com/20230710/russias-it-brain-gain-professionals-return-home-reversing-long-time-trend-1111786475.html. [↩]

- US State Department, “NSC 20/1, US Objectives With Respect to Russia,” August 18, 1948, https://archive.org/details/NSC201-USObjectivesWithRespectToRussia/. “We have already seen that among the existing and potential opposition groups there is none which we will wish to sponsor entirely and for whose actions, if it were to obtain power in Russia, we would wish to take responsibility.” [↩]

- Benjamin Tromly, Cold War Expiles and the CIA. Oxford University Press, 2019. p. 282. [↩]

- See more details in our book The Compatriots. [↩]

- Andrei Soldatov and Irina Borogan, “Paranoia and Poison — the Kremlin Panics Over Exiles,” The Center for European Policy Analysis, May 30, 2023, https://cepa.org/article/paranoia-and-poison-the-kremlin-panics-over-exiles/ [↩]

- Soldatov and Borogan, “Paranoia and Poison — the Kremlin Panics Over Exiles” [↩] [↩]

- Ibid [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Interview with Mark Palmer,” Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project, Library of Congress, October 30, 1997, https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/mss/mfdip/2004/2004pal02/2004pal02.pdf. [↩]

- New York Times, “Émigrés’ Fears Cited: Countess Tolstoy Calls Exiles in US Target of Soviets,” May 24, 1956. [↩]

- https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2023/mar/30/cyberwarfare-leaks-show-russian-army-is-adopting-mindset-of-secret-police [↩]

- https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/6121954?utm_campaign=push&utm_source=kommersant [↩]

- Andrei Soldatov and Irina Brogoan, “Kremlin Crosshairs Focus on Exiles,” The Center for European Policy Analysis, January 13, 2023, https://cepa.org/article/kremlin-crosshairs-focus-on-exiles/ [↩]

- Telegram. “Дмитрий Медведев.” Accessed December 5, 2023. https://t.me/medvedev_telegram/245. – Irina Borogan and Andrei Soldatov, “Kremlin Crosshairs Focus on Exiles,“ Center for European Policy Analysis, January 13, 2023. https://cepa.org/article/kremlin-crosshairs-focus-on-exiles/. [↩]

- Authors’ conversation with Arno [↩]

- Authors’ conversation with Gudkov [↩]

- “Русский антивоенный комитет в Швеции” признан нежелательным. Радио Свобода, January 11, 2023, https://www.svoboda.org/a/russkiy-antivoennyy-komitet-v-shvetsii-priznan-nezhelateljnoy-organizatsiey/32219341.html [↩]

- Sentyackov. 2023. “Russian Anti-War Committee in Sweden – Faces and Morals.”(a blog post in Russian). News2.ru, August 12. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://news2.ru/story/667437/. [↩]

- Dvinsky, Konstantin. 2023. “Persecuting the Church and Raising Funds for the Ukrainian Armed Forces: Russian Refugees Create a ‘Police Committee’ in Sweden.” (A blog post in Russian). Tsargrad.tv, August 3. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://tsargrad.tv/news/travjat-cerkov-i-sobirajut-dengi-na-vsu-beglecy-iz-rossii-sozdali-v-shvecii-policajskij-komitet_838863. [↩]

- Authors’ conversation with activists in Stockholm [↩]

- “Kirovsky District Court of Saint Petersburg Fines Russian Citizen Marina Bluma After Participating in Protest Actions in Sweden.” (A blog post in Russian). Ruletka.se, September 28, 2023. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://ruletka.se/2023/09/29/sud-v-peterburge-oshtrafoval-rossiyanku-za-akciyu-u-posolstva-v-stokgolme/. [↩]

- Caucasus, RFE/RL’s Echo of the. “Russian Activist Missing in Georgia May Be in Russian Custody.” RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Accessed December 5, 2023. [↩]

- Authors’ conversation with the Insider’s editor; The Insider. “Журналистка the Insider Марфа Смирнова рассказала об угрозах своей семье. От нее требуют прекратить работу и присылают прослушку близких.” Accessed December 5, 2023. https://theins.ru/news/263681. [↩]

- “The Russian writer was removed from the festival program due to the protest of Ukrainian poets,” Oceania TOPNews.MEDIA, May 9,2023, https://au.topnews.media/2023/05/09/the-russian-writer-was-removed-from-the-festival-program-due-to-the-protest-of-ukrainian-poets/, Jennifer Schuessler, “Journalist Resigns From Board After PEN America Cancels Russian Writers Panel,“ The New York Times, May 16, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/16/arts/16pen-masha-gessen-ukraine.html. [↩]

- Soldatov and Borogan, “The Russians Who Went West: A Lost Generation of Emigres” [↩]

- Smirnov, Leonid. 2019. “Interview with Igor Ivanov, Chairman of the Russian All-Military Union, Former Head of the Political Department of the DPR Army: ‘We Were Volunteers of the Crisis Hour.” (in Russian). Rosbalt, August 17. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://www.rosbalt.ru/world/2019/08/17/1797705.html [↩]

- Ivanov, Igor and Dmitry Sysoev. 2023. “The Trap of Resovietization – The Path to the Country’s Collapse”. (in Russian) February 15. Livejournal of the Russian All-Military Union. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://pereklichka.livejournal.com/2670124.html. [↩]

- Authors’ conversation with US diplomats in London [↩]

- Authors’s conversation at FCDO [↩]

- Authors’s conversation at NATO HQ in Brussels [↩]

- Max Seddon. “Russia’s opposition fails to unite against Putin,“ Financial Times, June 12, 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/17acd2fc-fc81-4238-ac29-ddbf82702c24 [↩]

- “Estonia Will Not Allow Russians Fleeing Mobilization to Cross Border,“ Estonian Public Broadcasting, April 17, 2023, https://news.err.ee/1608950720/estonia-will-not-allow-russians-fleeing-mobilization-to-cross-border. [↩]

- “Estonia Will Not Allow Russians Fleeing Mobilization to Cross Border,“ Estonian Public Broadcasting [↩]

- “Russia’s TV Rain Receives Dutch Licence after Ban in Latvi,” Lithuania National Radio and Television, January 10, 2023. https://www.lrt.lt/en/news-in-english/19/1863101/russia-s-tv-rain-receives-dutch-licence-after-ban-in-latvia. [↩]

- Authors’ conversations with TV Dozhd executive; Видео. “Главред ‘Дождя’: мы остаемся ориентированным на российскую аудиторию телеканалом, несмотря на смену локации,” November 17, 2022. https://rus.postimees.ee/7650840/glavred-dozhdya-my-ostaemsya-orientirovannym-na-rossiyskuyu-auditoriyu-telekanalom-nesmotrya-na-smenu-lokacii [↩]

- Andrei Soldatov and Irina Borogan, “Escape from Moscow,” Foreign Affairs, May 13, 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/russian-federation/2022-05-13/escape-moscow [↩]

- Радио Свобода. “В аэропорту Еревана была задержана, а затем отпущена разыскиваемая Россией россиянка, которой Киев предоставил статус беженца,” July 19, 2023. https://rus.azatutyun.am/a/32510618.html. [↩]

- AP News. “Father of Girl Who Drew Anti-War Art Extradited to Russia,” April 12, 2023. https://apnews.com/article/russia-ukraine-war-art-crackdown-father-462517b250d0ee3268fdd43f424b3a1b.. [↩]

- https://www.svoboda.org/a/mediamenedzhera-mityu-aleshkovskogo-ne-pustili-v-gruziyu/32023113.html [↩]

- Anastasia Tenisheva, “Rising Numbers of Russians Barred From Georgia, Activists Say,“ The Moscow Times, September 8, 2022, https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2022/09/08/rising-numbers-of-russians-barred-from-georgia-activists-say-a78742. [↩]

- “Редактора подкастов ‘Холода’ Алексея Пономарева не пустили в Грузию – SOVA,” December 11, 2022. https://sova.news/2022/12/11/redaktora-podkastov-holoda-alekseya-ponomareva-ne-pustili-v-gruziyu/. [↩]

- Tata Shoshiashvili, “Russian Women’s Rights Activist Barred from Entering Georgia,“ Open Caucasus Media, Feburary 13, 2023, https://oc-media.org/russian-womens-rights-activist-barred-from-entering-georgia/ . [↩]

- Dzyadko, Tikhon. 2023. “Russian Journalist Filipp Dzyadko Denied Entry into Georgia,“ (in Russian) Meduza. Feburary 20. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://meduza.io/en/news/2023/02/20/russian-journalist-filipp-dzyadko-denied-entry-into-georgia. [↩]

- Эхо Кавказа. “Михаил Фишман: Меня не пустили именно потому, что я – известный журналист в России,” March 6, 2022. https://www.ekhokavkaza.com/a/31739068.html. [↩]

- Lana Kokaia and Tony Wesolowsky, “Wanted In Ukraine, Welcomed In Georgia? Pro-Russian Separatist Supporter Trades Crypto In Tbilisi“., Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, September 7, 2022, https://www.rferl.org/a/georgia-deev-ukraine-cryptocurrency-separatists-russia/32021272.html. [↩]

- Times, The Moscow. “Former Presidential Guard Jailed for 6 Years for Deserting Russian Army.” The Moscow Times, March 24, 2023. https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2023/03/24/former-presidential-guard-jailed-for-6-years-for-deserting-russian-army-a80601 [↩]

- Current Time, “Russian Ant-War Activist Deported From Kyrgyzstan Charged With Arson Attack,” RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty, June 06, 2023. https://www.rferl.org/a/russian-activist-rozhkov-deported-kyrgyzstan-arson-charged/32447371.html. [↩]

- Baktygul Osmonalieva, “Term of detention of Russian activist extended in Bishkek” 24.kg news agency, July 06, 2023. https://24.kg/english/269724_Term_of_detention_of_Russian_activist_extended_in_Bishkek/. [↩]

- Chris Rickleton, “Russia’s Net Tightens Around Dissidents Sheltering In Kyrgyzstan“. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, June 17, 2023, https://www.rferl.org/a/kyrgyzstan-russia-ukraine-war-dissidents-targeted/32463479.html. [↩]

- “Russian Activist Found in Moscow Jail After Disappearing in Kyrgyzstan,” The Moscow Times, Nov 3, 2023, https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2023/11/03/russian-activist-found-in-moscow-jail-after-disappearing-in-kyrgyzstan-a82993. [↩]

- Pyotr Kozlov, “Activist’s Ordeal at Belgrade Airport Signals Trouble for Anti-War Russians in Serbia,“ The Moscow Times, July 14, 2023, https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2023/07/14/activists-ordeal-at-belgrade-airport-signals-trouble-for-anti-war-russians-in-serbia-a81845. [↩]

- Authors’ conversation with the activists of the Russian democratic society in Serbia. [↩]

- Authors’ conversation with the activists of the anti-war group in Hungary. [↩]

- President of Russia, “Law Ratifying Agreement Between Russia and Turkey on Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Cases and Extradition,“ March 7, 2017, http://en.kremlin.ru/acts/news/53993. [↩]

- “The Prosecutor General’s Office of Russia and the Ministry of Justice of Turkey Signed a New Two-Year Cooperation Program”. (In Russian). TASS, November 9, 2022. https://tass.ru/politika/16278783. [↩]

- Authors’ conversations with émigrés in Europe. [↩]

- “Moscow, Ankara Find New Ways to Extradite Criminals,“ Sputnik International, April 3, 2023, https://sputnikglobe.com/20230403/moscow-ankara-find-new-ways-to-extradite-criminals-1109076324.html. [↩]