The social media channels are alive with grainy footage of tanks and explosions in Southern and Eastern Ukraine. There are statements everywhere that Kyiv’s long-expected counteroffensive is underway, which is causing some excitement and trepidation. The offensive is incredibly important for Ukraine’s future.

But when assessing what’s actually happening, it’s useful to understand some key facts. There is a big difference between starting an offensive, and the main attack or main effort of the operation. The offensive has clearly started, but not I think the main attack.

When we see large, armored formations join the assault, then I think we’ll know the main attack has really begun. To date, I don’t think we’ve witnessed this concentration of several hundred tanks and infantry fighting vehicles (IFVs) in the attack.

A Ukrainian tank battalion normally has 31 tanks. An armored infantry battalion would have about the same number. Add in armored vehicles carrying engineers, air defense, logistics, and so on. An armored brigade would likely have three tank battalions and one or two mechanized infantry battalions. In total, then, an armored brigade is going to have 250-plus armored vehicles of different types.

I estimate that the Ukrainians have put together anywhere from seven to 12 armored brigades. Some may have only Ukrainian or captured Russian equipment, and others will have a mix of Western-provided kit.

When we see two or three of those brigades (around 500-750 armored vehicles) focused on a narrow front, it will then be possible to say that the main attack has probably started and where it’s happening. But even then, be careful. The Ukrainian General Staff will want to keep the Russians guessing about the location of the main attack for as long as possible, and they won’t be too bothered (and will probably welcome) Twitter getting it wrong.

If the West provides everything the Ukrainian Armed Forces (UAF) need, especially long-range precision weapons, then I still anticipate that Ukraine can liberate Crimea, the decisive terrain of this war, by the end of this summer, that is to say, by the end of August. This is one of the aims of the offensive, I believe. At that point, the UAF’s long-range precision weapons could reach Sevastopol, Saky, Dzankoy, and other key Crimean targets, and that would allow them to make the peninsula untenable for Russian forces. That’s why the UK’s delivery of Storm Shadow air-launched cruise missiles with a range of 155-plus miles, was such an important contribution.

I hope the Biden Administration will finally relent and give short-range (up to 300km or 186 miles) ground-to-ground ATACMS ballistic missiles to Ukraine. That would mark a decisive contribution to what Ukrainian forces can achieve on the ground by giving the offensive an enormous boost.

Some have dated the start of this campaign to June 4, two days before Russia’s sabotage of the Kakhovka Dam on the Dnipro River on June 6. That was likely the moment when General Valerii Zaluzhny, the UAF commander-in-chief, decided — in my view — that his three preconditions had been met and that he could therefore give the green light. He would have asked:

- Is there enough combat power (armored brigades with tanks, infantry fighting vehicles, engineers, artillery, air defense and logistics) to be able to penetrate the Russian linear defenses and achieve their assigned tasks, which probably includes cutting the “land bridge” from Russia to Crimea, and also securing the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant?;

- Have Russian defenses and logistics been sufficiently degraded; has the Russian rear area and transportation network been adequately disrupted; and are the Russian leadership confused enough as to the aim and timings of the UAF offensive?; and

- Is the ground dry enough to support the movement of hundreds of heavy, tracked, armored vehicles?

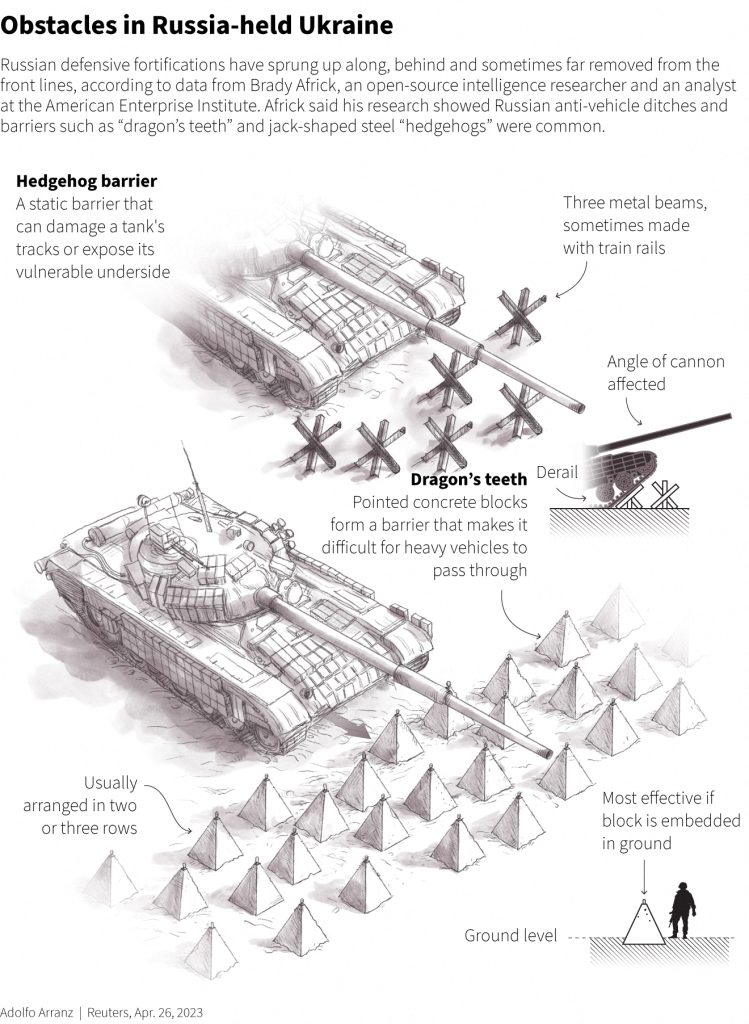

Lined up in defensive positions before the UAF assault units are the Russians, sitting behind hundreds of miles of trenches with bunkers, minefields, anti-tank ditches, and “Dragons Teeth” obstacle belts. But these defenses are only as good as the soldiers occupying them and covering those obstacles. I’m not impressed with the fighting capabilities of the Russians in most places, and the vicious in-fighting we see between the various Russian leaders, (e.g., warlords like Prigozhin and Kadyrov) highlights the lack of cohesion on the Russian side. I imagine the UAF will exploit this.

So far, it seems that the Ukrainians are still probing, pressing, looking for vulnerabilities to exploit, reinforcing local tactical success where they find or create it. That's one of the benefits of their adoption of Western-style tactical command and control where lower-level leaders can make decisions on their own. And some of what we are seeing is intended, perhaps, to confuse the Russians as to where the main attack will eventually be delivered. To show a Leopard on the battlefield at such an early stage was probably, in my view, intended to draw a lot of attention to that area, perhaps as a decoy. I cannot know that, but it's something I would have done, given all the attention in the media about these excellent tanks.

As always, those taking part in the fighting face not only enemy deception but also the sheer confusion of combat. The fog of war really does affect commanders in the field. I always had great difficulty visualizing and understanding what was going on during a fight — as a brigade commander and corps chief of operations in Iraq, and later as Director of Operations in Kandahar, Afghanistan — even though we had the latest command and control systems. A commander is still dependent on the reports from forward commanders actually engaged at the battle area’s forward edge. Drones help give some overview, but it's still a challenge. That's why it is essential to trust subordinate commanders to understand the overall plan and continue making good decisions in the heat of battle.

Even so, there are going to be losses. The destruction of a single Leopard caused a lot of excitement on Twitter, but it was actually recovered from the battlefield so that it could be repaired and put back in the fight. That's impressive. It's what we practice in the US Army, and it’s worth noting the UAF’s achievement in doing the same.

There is much uncertainty, but of one thing we can be sure — the Ukrainian General Staff has done a superb job protecting information in order to prevent the Russians from knowing what's happening and enabling them to prepare for the attack.

The uncertainty in Russian minds may have been one reason for their sabotage of the Kakhovka Dam. Quite apart from its horrific humanitarian and ecological consequences, the flooding of low ground and widening of the Dnipro may have delayed UAF offensive operations in that area for a time. But there are expert voices saying the floodwaters will subside within the next five to seven days, and the ground will rapidly begin to dry in the summer heat. So the likely intended effect hoped for by the Russian side — of making crossings of the Dnipro harder — is probably going to be relatively short-lived.

Meanwhile, I have no trust whatsoever about any report from the Russian side on the dam’s demolition or about anything happening on the line of contact. The Ukrainians, of course, are very disciplined in protecting information and are also very good at controlling the narrative. We’ll know more soon.

So what does Ukraine need as it engages in this great national effort? It needs advocates, and it badly needs ATACMS.

Ben Hodges is Senior Advisor to Human Rights First, a non-profit, nonpartisan international human rights organization based in New York, Washington DC, and Los Angeles. Prior to joining Human Rights First, he held the Pershing Chair in Strategic Studies at the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA).

Europe’s Edge is CEPA’s online journal covering critical topics on the foreign policy docket across Europe and North America. All opinions are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the position or views of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis.