The large-scale Russian attack aimed at the complete capture of Avdiivka has failed. The Kremlin has thereby flunked one of its self-imposed military objectives. Again.

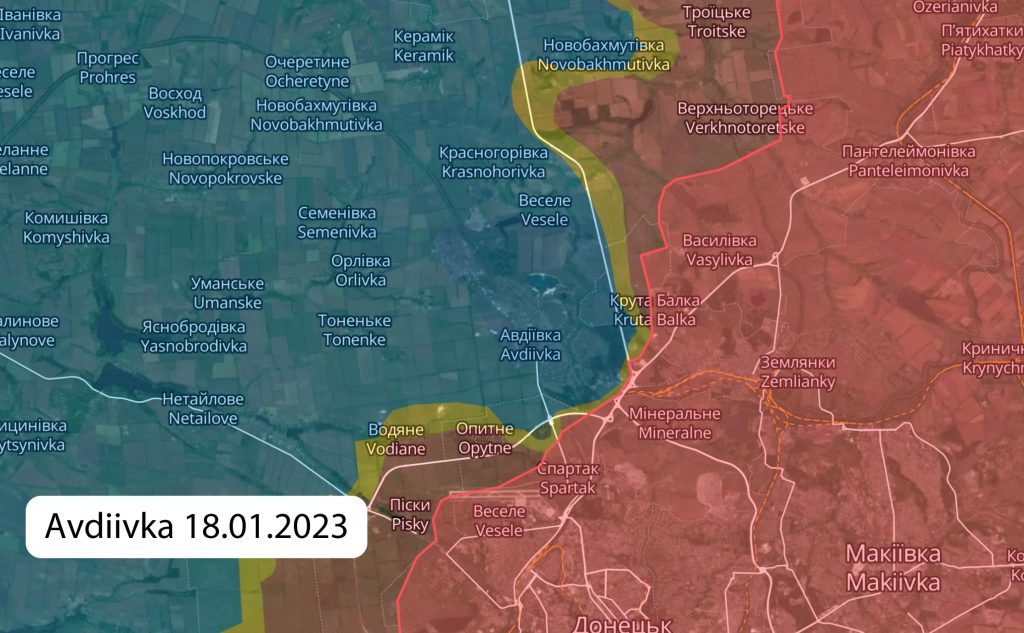

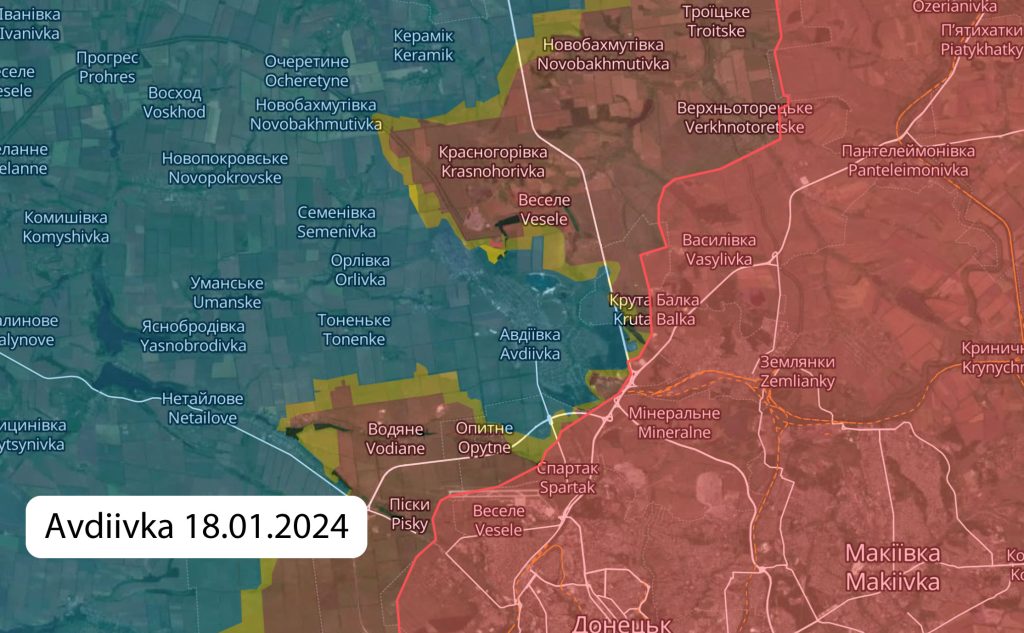

Russia has so far lost around 20,000 soldiers killed and wounded at Avdiivka, with drones capturing images of corpses strewn across the battlefield. Around 500 main battle tanks, infantry fighting vehicles, self-propelled howitzers, and other vehicles were destroyed. With this effort, Russia has so far gained around 12-15km (7.5-9 miles) of land north of Avdiivka without being able to take the city.

Since Russia regained the initiative along the entire front line at the end of last year, its forces have nevertheless been advancing along several sections of the front.

In the northeast, it continues to direct heavy fire on Ukrainian territory to the north and south of Kupyansk. The course of the front remains unchanged so far, although Ukraine has evacuated some villages there.

Following the failure to take Avdiivka, the next major Russian offensive effort is expected to take aim at Kupyansk. Ahead of Russia’s presidential elections in March, there is political pressure to show some kind of presentable success. This is similar to last year’s battle to take the town of Bakhmut, where political considerations seemed as important, or even subordinate, to the military goal. As many as 30,000 men died or were wounded in that campaign.

Russia continues to attack west of Bakhmut and west of Mariinka, gaining a few hundred meters of terrain in both directions.

Between Verbove and Robotyne, where Ukraine’s main summer and autumn offensive took place, Russia has retaken some positions that Ukraine had recaptured at great cost during the earlier fighting.

The losses of individual positions are psychologically bitter for Ukraine. However, the new defensive strategy of not holding every meter, but seeking to delay while concentrating on forcing Russia to pay a high human and material price, makes military sense.

In addition, Russia is intensifying combined air strikes using cruise missiles, ballistic missiles, drones, and converted S-300 missiles.

These target infrastructure and are designed to cause terror to the civilian population on the one hand, while hitting Ukrainian arms industry production on the other. They are also used for propaganda on Russian television.

So what about the rest of 2024? The Russian aim appears to be a continuation of the war at least until the US presidential elections, gaining as much territory as possible regardless of losses and defending the conquests made so far.

Credit: @War_Mapper @AndrewPerpetua

Russia is currently recruiting around 1,000 new soldiers per day. This is below the threshold of a publicly visible large-scale mobilization but means that even extreme losses of men, such as at Avdiivka, can be sustained.

Russia has ramped up its arms production, is successfully circumventing sanctions, and currently feels encouraged by the domestic political blockade of military aid for Ukraine in the US, and stumbling efforts to agree European Union (EU) assistance.

After Ukraine, the US, and other partners have been talking publicly for months about increasing domestic arms production and joint production in Ukraine, Russia is now targeting its arms factories with missiles.

Meanwhile, its army still needs much more artillery ammunition and there is an urgent need for higher production in Europe (though Sweden, Finland, Norway, Germany, the UK, and others are making significant investments in extra capacity.)

The first attempts to defend against Russian missiles with electronic warfare and FrankenSAM (post-Soviet systems retrofitted with modern technology) were successful, so this should be multiplied and expanded very quickly.

Ukraine’s partners should once again try to bring even more modern air defense systems to Ukraine. In the future, the possibility of intercepting Russian missiles at range from outside Ukraine must also be considered.

Ukraine also needs supplies of precision weapons. France recently led the way here with 40 additional SCALP-EG cruise missiles and a promise of 50 precision-guided A2SM missiles a month. ATACMS with monobloc warheads, 100-mile range GLSDB precision bombs, and Germany’s Taurus should quickly follow.

Repair workshops and maintenance facilities for main battle tanks and infantry fighting vehicles must be brought closer to the front, also through cooperation between Western companies and Ukraine. The industry’s air defense must also be considered.

F-16s, Gripen, and Mirage aircraft should be delivered and deployed to enable action near the front against Russian aircraft with upgraded glide bombs, against which Ukraine has so far been almost defenseless.

It would be of immense help to Ukraine if Western countries were to better prevent the use of modern computer numerical control (CNC) machinery, components, and technologies for the Russian arms industry. Shrugging this off is a mistake.

Ukraine needs more drone defense and components for its successful drone programs, which can currently at least partially compensate for the lack of ammunition and resources.

And lastly, the country needs a change of political strategy from key supporters.

Once aid expands to allow greater Ukrainian military assertiveness, instead of pure survival, and simultaneous long-term security commitments, including the prospect of NATO membership at the alliance summit in July, a path to peace and stability would be possible by this year’s end.

Nico Lange is a Non-resident Senior Fellow with the Transatlantic Defense and Security Program at the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA). He is also a Senior Fellow at the Munich Security Conference in Berlin and Munich and teaches military history at the University of Potsdam. Lange served as Chief of Staff at the German Ministry of Defense from 2019-2022.

Europe’s Edge is CEPA’s online journal covering critical topics on the foreign policy docket across Europe and North America. All opinions are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the position or views of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis.