High expectations and disappointing outcomes. That is the Czechs’ story since the 1989 Velvet Revolution. That fairytale episode (which I witnessed as a young foreign correspondent) not only put Václav Havel in Prague Castle. It laid the foundation for a vigorous civil society and the country’s reintegration into the European mainstream. But it also presaged three decades of political and economic chicanery, exemplified by the two-term presidency of the erratic, anti-Western Miloš Zeman, and by the seemingly unstoppable career of the oligarch and populist politician, the former prime minister Andrej Babiš.

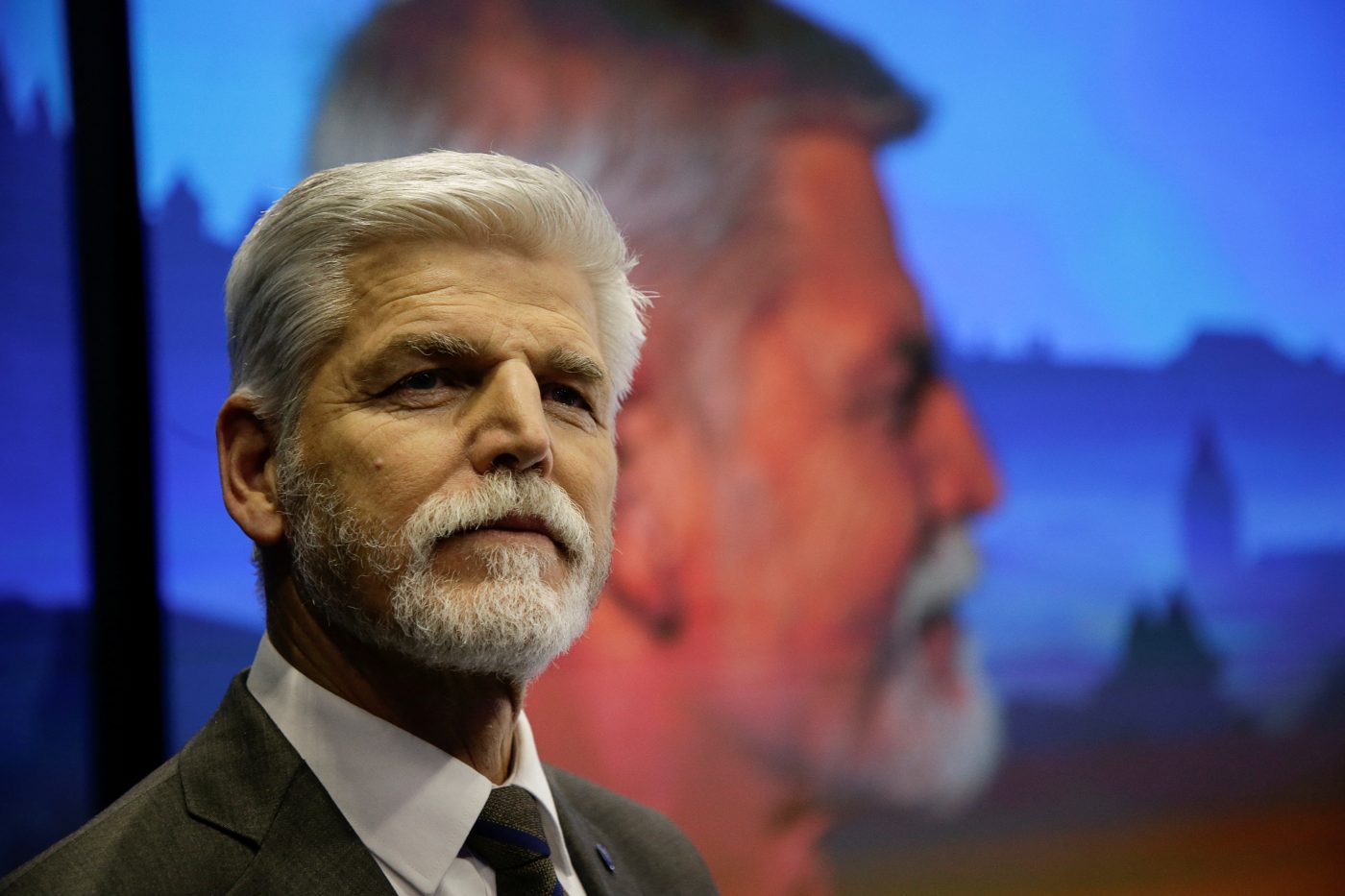

This week marks the end of that era, and the beginning, perhaps, of a more hopeful one. Zeman’s successor as head of state is Petr Pavel, a retired general with a distinguished record of active service in ex-Yugoslavia, and at NATO, where he chaired the alliance’s military committee. Pavel stands firmly in the liberal, internationalist tradition of Havel and (fans venture to hope) Czechoslovakia’s revered pre-war president Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk.

The contrast with Babiš could hardly be sharper. The Slovak-born businessman’s career has been dogged by controversy over his past cooperation with the communist-era secret police, his post-1991 business methods and tactics, his evasion of legal and public scrutiny, and his bullying of critics. His fortunate acquittal on charges of stealing European Union subsidies made him, for a while, the favorite to win the presidential contest. During the campaign, he bluntly rejected his country’s obligations under NATO’s collective-defense clause, saying that as commander-in-chief, he would not send Czech soldiers to defend Poland or the Baltic states if they were attacked. Though he later backtracked on that, his posters, which plastered the country, carried slogans such as “I am not going to drag Czechia into war — I’m a diplomat, not a soldier”, and “Vote Peace, Vote Babiš.”

But neither his fortune ($4 billion by most efforts), nor his political machine, nor his media empire, nor his crowd-pleasing anti-migration messaging, nor even a hurriedly acquired beard, were enough to bring victory. Pavel defeated Babiš by 58% to 42% in a run-off election, a landslide by Czech standards.

The Czech presidency is mainly ceremonial. The head of state nominates senior figures, such as top judges and the central bank chief, and can choose a prime minister after a parliamentary election. The president plays a role in foreign policy, too, chiefly through public speeches and visits. There will be plenty to do there, smoothing feathers ruffled by the chain-smoking, bibulous and hard-talking Zeman. Pavel’s role in saving besieged French soldiers in 1993 will make him a welcome guest in Paris. At home, in contrast with Babiš’s scorched-earth rhetoric, the president-elect has taken an emollient tone, urging Czechs to shun political polarisation and to talk more to each other.

The wider lesson is that given a strong candidate and a strong campaign — something signally absent in previous presidential contests — a mainstream political campaign can beat even an unscrupulous and well-connected populist opponent. That lesson will not be lost in other countries. Next-door Slovakia is mired in a political crisis pending early parliamentary elections. Poland also faces regular elections in which the ruling Law and Justice party, yet again, faces a divided centrist and left-wing opposition. Hungary’s political opposition did unite for elections last year but failed to dislodge Victor Orbán, who, as prime minister, has decried sanctions on Russia, criticized Ukraine, and clashed with the EU. That has gained him a strong international following among some foreign conservatives.

But history shows that the Czechs, too, can play an outsize role in international politics. Under the steely, soft-spoken Pavel, those times may be returning.

Europe’s Edge is CEPA’s online journal covering critical topics on the foreign policy docket across Europe and North America. All opinions are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the position or views of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis.