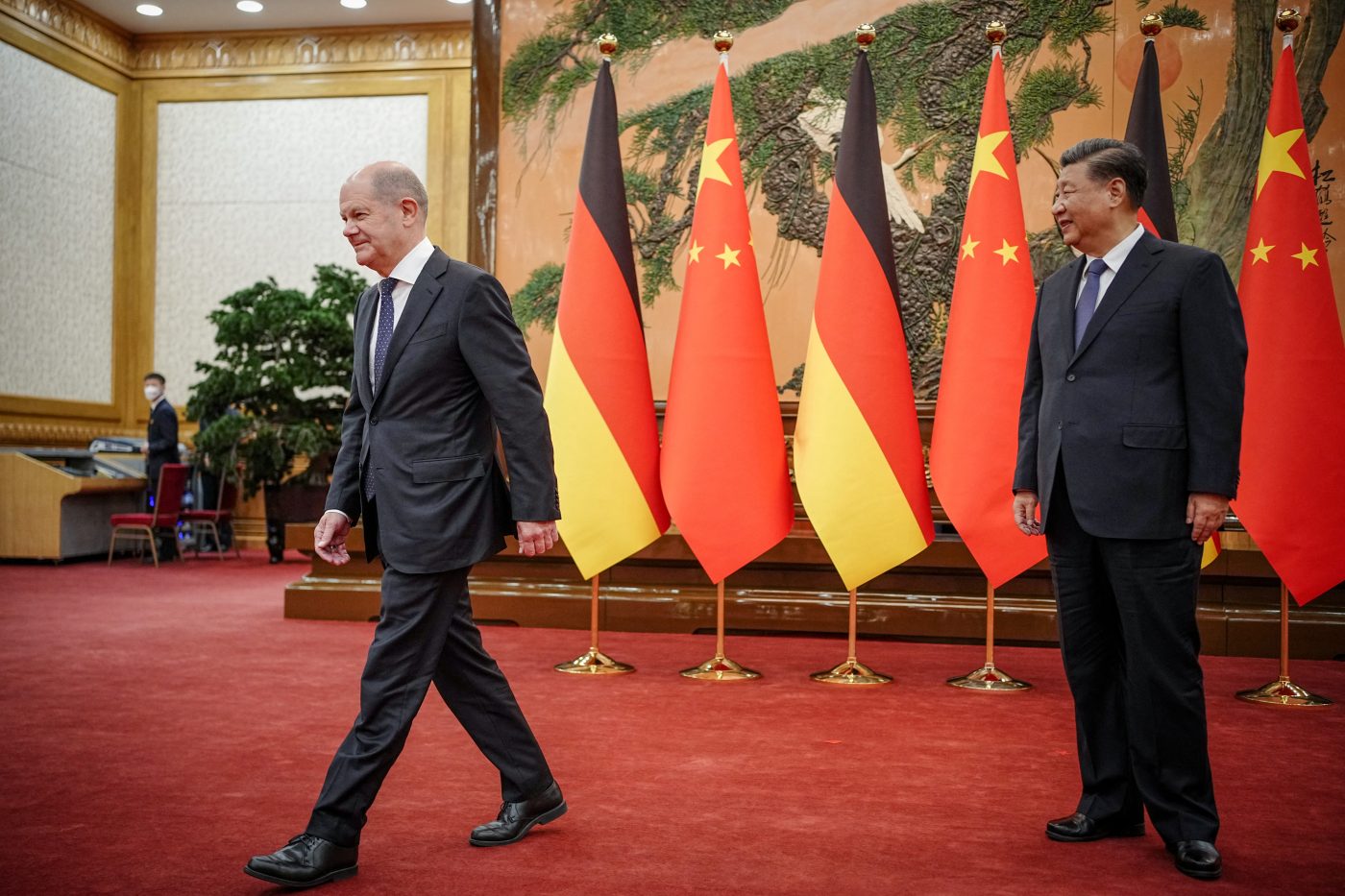

Dependency on China challenges Germany. Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock presented the country’s inaugural China strategy this month, emphasizing the country’s need to reduce dependence on “key technologies such as semiconductors, artificial intelligence, and green technologies.” At the same time, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz tweeted that his government does not want to “disconnect” from China, just “avoid critical dependencies.”

It’s a fine line, aggravated by tensions within Germany’s ruling coalition. Foreign Minister Baerbock comes from the Green party, skeptical of China. Chancellor Scholz is a Social Democrat focused on creating job opportunities. Add to the mix the Free Democrats’ pro-business finance minister, Christian Lindner, and the result is often political confusion.

Among European Union countries, Germany has the strongest economic ties with Beijing. China is its largest trading partner, with €298 billion in goods exchanged in 2022. While Berlin exports more to the US than to China, marquee companies led by Volkswagen, BASF, and Siemens are increasing their investments. Direct German investments in China increased by an estimated 11% in 2002.

Chinese investments inside Germany are just as controversial. In May, the government approved a controversial deal allowing Chinese company COSCO to buy a minority stake in the Hamburg port. The Free Democrats demanded that COSCO’s stake be capped, while Scholz’s Social Democrats were keen on pushing through the deal and won out.

Perhaps the biggest German fear is becoming dependent on China for key raw materials. Germany already relies on China for “various metals and rare earths” crucial to chipmaking, the country’s new German strategy acknowledges. Some 94% of the EU’s rare earths come from China, a dependency reinforced by China’s recent embargo on exports of Gallium and Germanium.

In response, Berlin aims to diversify supplies of raw material imports — and bring back home production of key technologies. Industrial policy is in vogue. The German government plans to invest more in “emerging key technologies” and use “strategic foresight” to identify them. Germany is already at the center of Europe’s effort to boost semiconductors back to the Old Continent, with Intel benefiting from billions of euros of subsidies to build a €17 billion mega fab in Saxony-Anhalt.

Perhaps the biggest challenge centers on telecom infrastructure. In 2022, Chinese vendors supplied 59% of the 5G RAN in Germany. Huawei enjoys a higher market share in Berlin than in Beijing, where it shares the market with ZTE and other vendors. Germany’s largest operator Deutsche Telekom maintains a strategic partnership with Huawei — even though the European Commission banned Huawei and ZTE in mid-June from its internal networks and urged the EU member states to exclude high-risk vendors.

The new China strategy lists telecommunications infrastructure as critical for national security. It orders the Federal Office for Information Security to ensure that telcos disclose “the planned first use of a critical component.” But this transparency does not yet translate into an order to rip and replace Chinese telecom equipment.

Chinese cyber offensives represent another threat. The new security plan warns against “Chinese cyber actors [that] are engaged in economic and academic espionage in an attempt to gain access to German corporations’ trade and research secrets.”

A related, perhaps even more dangerous fear is Chinese disinformation disrupting German democracy. The new strategy calls for German schools, universities, teachers, and researchers to ensure that Chinese government-sponsored Confucius Institutes uphold “the principle of the freedom of science, research, and academic teaching.”

Germany is waking up to the perils of overreliance on China. It is on board with the Western strategy of “de-risking.” The unanswered question is whether is consensus-based coalition government can achieve this goal.

Théophane Hartmann is a tech reporter for EURACTIV France. He previously worked as an IT Strategy consultant.

Alina Clasen, a tech reporter for EURACTIV Germany, contributed research.

Bandwidth is CEPA’s online journal dedicated to advancing transatlantic cooperation on tech policy. All opinions are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the position or views of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis.