Hungary blocked a European Union (EU) statement criticizing China for its repressive new Hong Kong security law on April 16, marking its latest effort to shield China from condemnation. Hungary’s justification, according to one senior EU diplomat, was simply that “the EU already has too many issues with China.”

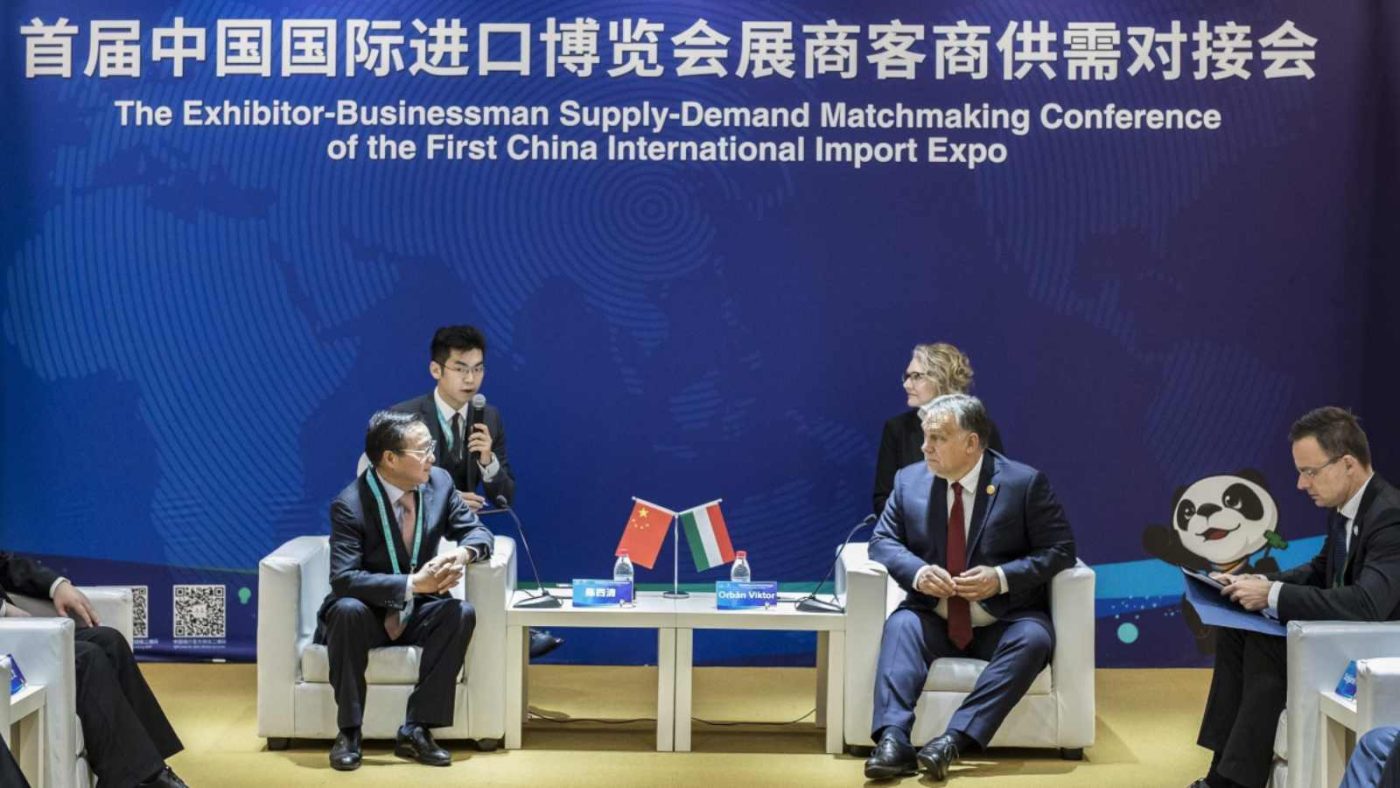

Hungary has embraced Chinese investment, part of a largely positive relationship with the country. Since 2013, China has invested (or promised) billions of dollars in infrastructure projects in central and eastern Europe, with Hungary becoming one of its biggest clients in the region. With an annual turnover of bilateral trade approaching $9bn, China is now Hungary’s largest foreign trade partner beyond Europe’s borders. The Chinese and Hungarian governments have also frequently engaged in bilateral talks and established a “comprehensive strategic partnership,” opening the door to deeper economic ties in the future. The relationship is built on mutual respect, says Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán.

Although Hungary sees its ties with Beijing to be beneficial, it has strained the relationship with the U.S. and the EU.

As a self-touted “illiberal democracy,” Orbán’s Hungary distances itself from its “traditional [European] democratic allies,” while drawing closer to countries such as Russia, Turkey, and China. As its political, economic, and technological ties with China grow stronger, so too does its threat to pursue a very different European model.

The U.S. is also concerned about China’s role in dividing the West, something spelled out by the-then U.S. Ambassador to Romania, who Adrian Zuckerman warned that: “The Chinese presence in the EU is a tremendous danger … Chinese businesses … are corrupt … underestimating that danger will bring no good to anybody in a free democracy.”

Specifically, the U.S. is concerned by the inroads made by the Chinese technology company, Huawei and its role in the development of Europe’s new 5G networks. In U.S. eyes, Huawei is an “an arm of the Chinese Communist Party…[that] could enable spying.” Despite this warning, Hungary continues to use the technology, part of a close relationship with the company which includes the siting of a large supply center in Hungary and the planned opening of a large Huawei research facility in Budapest. The company says it has invested $1.5bn in the country since 2005.

Hungary’s continued dismissal of U.S. advice is a source of tension between the governments; it also renders it more difficult for the U.S. to develop a unified Western policy to counter Chinese influence.

For now, the Hungarian government views its partnership with China as a net positive. Péter Szijjártó, Hungary’s Minister of Foreign Affairs and Trade, said: “Huawei has been one of Hungary’s strategic partners since 2013, and the company has been intensively working to develop Hungary’s economy and the country’s ICT [information and communication technologies] ever since.”

It may be that a consistently divided European community and tense relationship with the U.S. will ultimately lead the government to rethink its policy choices. This shift, however, appears unlikely in the short-term.

Hungary is far from alone in resisting U.S. pressure regarding Huawei. Diverging policies highlight these divisions. Many states, such as Latvia, Estonia, Denmark, the United Kingdom, the Czech Republic, Romania, and Poland have followed U.S. policy and instituted a ban on the technology. Others, however, such as France, Germany, Belgium, Serbia, and Hungary, either currently use Huawei or have declared they are unlikely to ban it.

There are ways the U.S. can respond, and hopefully the EU too. Before night falls and the full effects of China’s economic Trojan Horse are felt, the West must:

- evaluate and quantify the threat China-Hungary ties may pose to the European continent, and

- develop short and long-term avenues for coordination and integration to challenge China’s growing dominance in technology.

President Joe Biden’s plan to “unite the economic might of democracies around the world” and proposals such as the “Transatlantic Trade and Technology Council” for coordinating joint U.S.-EU strategies to counter China are showing promise.

However, as long as major EU member states remain sympathetic to China, a truly unified strategy to reduce or remove China’s presence in Hungary – let alone the whole continent – will likely remain elusive.