Great power competition is accelerating in the High North (the Arctic), and critical and emerging technologies will decide whether authoritarian or democratic powers dominate the emerging domain.

Last year, Russia and China agreed to jointly develop the region economically and militarily, effectively ending the era when cooperative initiatives like the Arctic Council attempted to chart a path forward. The two countries also agreed to joint coast guard exercises, and increasingly, Russia is shipping oil to China via the Arctic Ocean. Russia holds the largest Arctic landmass and continues to heavily invest in Arctic defense infrastructure.

Seven of the eight Arctic Council states are NATO members and given the rising challenge, diligent and long-term security planning is critical. The Pentagon is responding with a forthcoming updated Arctic Strategy and has organized multiple Arctic military exercises in the last year.

But NATO cannot rely on yesterday’s approaches to technology and must evolve them for today’s High North, which presents national security challenges spanning geopolitics, economics, and the environment.

Yet, despite the scale of the challenge, the alliance can create asymmetric military advantages through effectively and deliberately developing new technology across several major issues in the High North..

First, approximately 25% of the Northern Hemisphere contains deep permafrost (perpetually frozen ground) which supports Arctic infrastructure. However, an estimated 30-85% of current subsurface permafrost will melt this century if global warming remains unchecked. This could wreak havoc on physical infrastructure in the Arctic, hindering military activity. Many Alaskan bridges are structurally deficient, while roads are reportedly sagging into the thawing ground already.

Rapidly deployable infrastructure can ensure mobility in the face of such decay. These structures must be durable, mobile, and modular to function in austere environments. Systems such as the M60 Armored Vehicle Launch Bridge (AVLB) are currently used for rugged terrain, which folds out a 60-foot bridge to cover large gaps.

Marshall Land Systems develops deployable infrastructure units, which serve as modular containers for a variety of functions, from medical treatment centers to machining workshops. HyWatts provides uninterrupted renewable power for these systems from a modular container in any environment using hydrogen as an energy storage medium. NATO’s High North countries will need to invest more in new deployable solutions to enable operability across Arctic missions, particularly during outright conflict.

They have little choice. Economic activity is accelerating in the High North, with the US NOAA Arctic Report Card noting satellite records showing shipping activity has significantly increased since 2009 as Arctic sea ice declines.

More activity means greater geopolitical risk and the need for greater preparation. Though contentious due to their contested connection with sea ice melt, icebreaking vessels are essential to maintaining year-round presence and transport in the Arctic. The US only possesses two such ships, both of which are at the end of their life cycles. China has four, and Russia has 40.

The US Coast Guard’s Polar Security Cutter program aims to build three heavy icebreakers this decade, but production is reportedly years behind schedule and, in either case, fails to meet the national need. Currently, the US lacks sufficient skilled labor to make enough of these technically complex ships. This needs to change, and joint NATO efforts could help ensure consistent regional access.

Second, with greater traffic across the region, NATO countries must have a greater ability to survey, document, monitor, and so detect foreign encroachment, understand the movement of goods and people, and track changes in topography caused by factors such as global warming.

Domain awareness is an ongoing challenge in countries with large Arctic land masses such as Alaska, where strained connectivity, power access, and extreme weather all hinder unmanned systems. NASA’s drone, Vanilla, flew for six hours in the Arctic totaling over 130 miles. Unique technology such as its internal heating system and anti-icing coating, if adapted to other robotic systems, could help make them more resilient, durable, and interoperable within the Arctic.

Additionally, space-based intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (SB-ISR) sensors are critical. However, satellites historically struggle with connectivity, signal fidelity, and resolution quality due to snowfall, cloud coverage, wind, and precipitation. To tackle these, Canada funded the Enhanced Satellite Communication Project – Polar (ESCP-P), which will enable narrowband and wideband satellite communications including beyond line of sight.

Polar-orbiting satellites, and the infrastructure to launch them, are also increasingly vital. Russia launched its Arktika-M satellite in December, the second of nine it plans to send into orbit by 2026. The seven NATO countries in the High North will need to expand their own space-based and ground-based communications, such as durable and portable 5G systems and polar-orbit satellites, to provide ubiquitous, rapid data transmission for NATO activity in the High North.

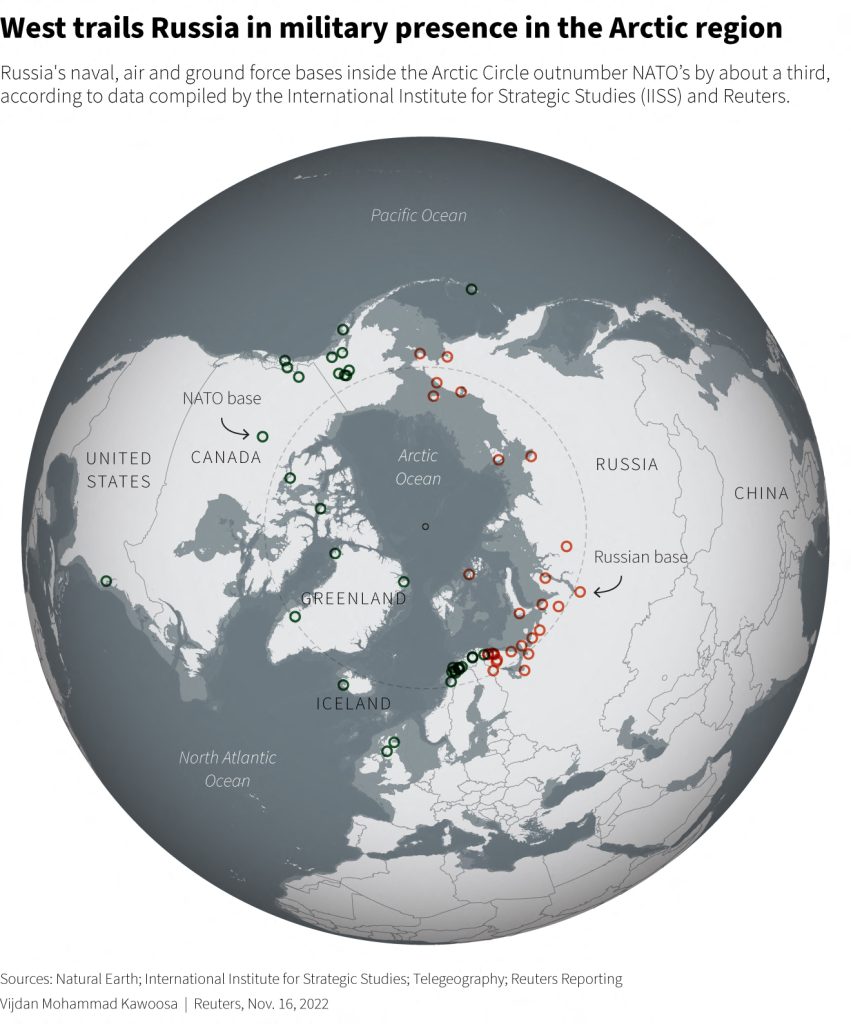

Third, for the alliance to have a consistent and comprehensive presence in the Arctic, it must winterize much of its current hardware and infrastructure. This “winterization” of legacy technology applies to ports, airfields, bases, and military equipment so they are survivable in the harsh Arctic climate. The Russians are “refurbishing airfields and renewing much of their defense architecture across the Arctic region,” according to Iris A. Ferguson, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Arctic and Global Resilience

Underwater and above-water capability should be a priority, and the US Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) has invested in multiple technologies to meet this need, including Saildrone’s uncrewed surface vehicles, and Strategic Robotic Systems’ underwater Fusion drone.

NATO as a whole must focus on these issues. Ongoing efforts in the broader defense community to bolster the West’s defense industrial base by investing in new technologies will be critical in the Arctic, but this will not be an easy process given that much of what’s needed is highly specialized and likely to result in relatively small-scale production.

Private sector funding will be harder to find, making government involvement a requirement. As a result, startups and mature companies alike face a constrained market opportunity, and constrained private investment, for developing defense and dual-use technologies suited for the High North. Addressing these challenges will require NATO nations, particularly the seven Arctic members, including the US, to seed demand through conception and funding to production.

Nicholas Nelson is the Senior Fellow for Emerging Tech & Policy at CEPA and is a Partner at MD One Ventures, Europe’s first defense and dual-use technology focused venture capital fund. In addition to this, Mr. Nelson’s research and analysis is focused on emerging defense and dual-use technologies. He also advises a range of deep tech venture-backed startups.

Andrew Stiles has advised executives on emerging technologies as a management consultant for nearly a decade. In this role, he has helped grow business groups focused on aerospace & defense markets from the first few employees to over 100. He also supports institutional venture funds in the US and UK, and is a Wharton MBA.

Kyra Terenzio is a management consultant specializing in emerging technology at a leading professional services firm, and has a B.S. in business administration from University of California, Berkeley’s Haas School of Business.

Europe’s Edge is CEPA’s online journal covering critical topics on the foreign policy docket across Europe and North America. All opinions are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the position or views of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis.