According to the Lithuanian General Encyclopedia, at least 132,000 people were deported to Siberia. More than 70% were women with children. In 1949 alone, my grandmother and her family were among 32,000 people exiled as part of Operation Priboi, which aimed to remove all potential opponents of the Soviet dictatorship from Lithuania. Only 60,000 returned.

This is a story of generational trauma. It is the story of my grandmother, Martina Martinaitienė, and my family, but it is also the story of my nation. It is not a traditional tale and its defining events are not well-known in the West.

When someone in your family experiences major trauma, you feel guilt for your whole life; guilt and pain, and you cannot explain how that feels to those whose families have never suffered anything similar. You feel pain for reasons you cannot even understand yourself.

I am sorry if I fail to entertain, but I will have achieved something if you shed a tear to join the rivers of tears that my family and my nation have shed as the result of the cruelties inflicted by our Russian neighbors. And you will understand why we now weep for Ukraine.

It was only when she reached her 80s that my grandma began to be more open about her life. She started buying books about the Soviet deportations. “Yes,” she would say with an odd and childish enthusiasm. “This was exactly what happened to us!” I realized that she was trying to grasp what had happened to her some seven decades earlier, when she was just nine and her life had taken a turn that no child should experience. She talked of the dead bodies being taken out of the cattle cars with a face that was absolutely calm.

It is very strange that a nine-year-old should encounter such profound issues. When I was nine, I threw a tantrum over a toy.

It was late March when the Russians came. I have no idea what the weather was like, but I assume, as it usually is in Lithuania — still frosty after the long winter. In a sense, a lucky time because those deported in 1941 left in mid-summer, so it must have been hard to know what clothes would be needed for a Siberian winter (if the officer was nice enough to let you take your clothes with you.)

Apparently, the officers who appeared to execute the deportation operation liked my grandmother, then so tiny that she was often mistaken for a younger child. They told her to run away. “But there were these two neighbors’ girls who were supposed to be deported one year before us and managed to get away,” she told me. “They never had a life. They would go from a village to village, they were even taken to neighboring Latvia (which was just across the forest), and the officers would keep searching for them.” Thus my grandma decided it would be safer to leave with her parents.

At this point, she already had three siblings: a brother who was eight, another brother of one, and a sister who was still a fragile newborn. The one-year-old brother was included on the list of those to be deported. The women of the village began negotiating with the Soviets and a to and fro began, as they bargained for the life of the smallest children. In the end, the two youngest remained behind. The girl, a premature and very weak baby, cried for its mother. Later great-great-grandma would pray she would die, the cursed little soul who had barely seen her mother who was now on her way to Siberia.

And that was it; the moment that a Lithuanian family changed forever.

When grandma was allowed to return from Siberia, she was shamed for losing her Lithuanian. I always thought (because I was told) that she could speak only in Russian and German (which she knew very well thanks to her German teacher, a so-called Volga German who had also been deported and who was her teacher and family friend in Siberia). But no, she spoke fluent Samogitian, one of the Lithuanian dialects. She just didn’t know how to standardize it and her communist teacher chose to shame her for it.

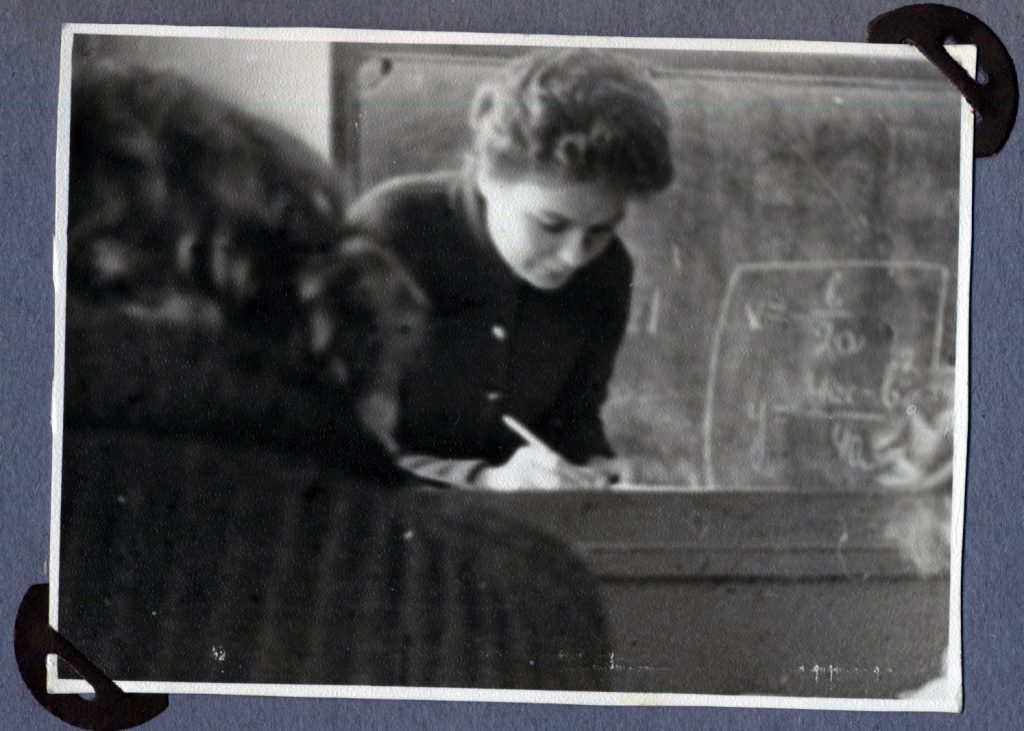

Back home, grandma did not have many options as a deportee, and yet she finally got lucky; she was able to become a schoolteacher and thus fulfill her professional dream. When she started work, she became an inspiration and a protector to all the misunderstood students. My mother, her daughter, always felt safe walking with her at night, because former students who had since grown up to become criminals respected and were grateful for her forbearance and support despite their troubled lives. She improved the grades for students born as deportees, as she knew that the ideologically conformist teachers of subjects like history or the Lithuanian language — which were used as instruments by the Soviet regime — would punish them for their origins. She even fought a school principal who demanded that students be tested for drugs, arguing that it would be a violation of their human rights (the Soviet Union was not renowned for its respect for such concepts. She could easily have been fired.)

Each trauma cascades down the generations, maiming not only those pitchforked into cattle cars, but those who came after them.

My great-grandmother saved everyone in her cattle car; she was a merchant’s daughter and cleverly chose all the right things for the long trip. But she couldn’t save herself from the deep, dark depression that followed. My mother remembered her collecting fairytales. “Only in fairytales does everything end well,” she would explain. Rumor had it that she — a beautiful young woman with big blue eyes — was also a multiple rape victim.

Firstly, her depressive states were extremely disturbing for her kids, whether that be through mood-swings, emotional distance and withdrawal, and entitlement. The children believed they must have done something for their mother not to love them. My grandma, who when small would not let this parent out of her sight, came to believe that great grandma had severed her affection. As the older woman lay dying, mother saw grandma crying next to the death bed and begging the old lady — already very weak and unable to walk, her big wide eyes still a signal of her youthful beauty —for answers.

“Mother, why have you never loved me? Why have you loathed me?” she asked. The desperately ill woman did not respond, she was too weak. But for my grandmother, this was simply confirmation of her unloved state.

My grandma’s sister — who had once covered for her brother and ended up being left with her grandparents in the village — shared this belief.

She died young. I grew up believing that the sister was mysteriously poisoned. But then grandma, already in her later years, explained that her sister had committed suicide. Once again, she blamed her mother. “She asked for money to attend a brother’s wedding. My mother declined. Then my sister threatened that she would show her what a real wedding was like, and she did that to herself. Half of us attended the wedding, the other half went to my sister’s funeral. Was it so much to ask for some pennies for a dress?”

The truth was that these people were so damaged by the course of their lives, that love was crowded out. When I grew up, I too suffered depression as the product of the dysfunctional mess that my family had become. The trigger in the case of my immediate family was my mother’s illnesses, which led to rejection by her family members. She seemed too weak and spoilt for them, leaving me alone to take care of her. This made me unable to build functional relationships, and left me so low that one night I decided to freeze myself to death, until someone talked me out of it.

In my memory, my grandma did not expect excessive respect towards her as a deportee. As a teacher, she did not want her generation’s trauma to fall heavily on the younger generation’s shoulders. And yet, when I would come back tired from a quick back-and-forth trip to Riga (my grandma lived in Šiauliai, 130 km — 81 miles — away), she would tell me she had spent a month in a cattle car on her way to Siberia. Or that my cousin and I did not understand life — we had not been deported and forced to sleep on Siberian moss.

Even though I was born in the 1990s, by which time Lithuania was once again independent, I grew up feeling blessed to meet foreign exchange students from Mexico and to realize we had watched the same cartoons as children. My parents did their best to drive me around Western Europe in the hope “that it will wash off the homo sovieticus mentality.” I felt uncomfortable and slightly embarrassed when someone from Western Europe would tell of how their parents traveled, because my parents couldn’t — firstly because the Soviet Union acted as a jailer to its citizens and later because the resurrected Lithuania had freedom but not money, at least to begin with. The Soviet Union disintegrated, its pieces landing where they fell, and citizens like me were left with the bruises.

I went to a therapist. We talked about my family story: my great-grandma who gave birth to many children, some of them in Siberia; my great-grandpa who was a political prisoner; another great-grandpa who walked all the way back home from Austria-Hungary as a prisoner of war (he managed to escape); my great-grandma who first thought her husband was killed in World War One and then her son in World War Two (both, in fact, had survived); my grandpa who was told not to return home because he was being hunted for deportation at that very moment; and finally, my grandma who was deported as a little girl, her family, the suicides, and broken lives. “Don’t be too harsh on them. They themselves really don’t understand what’s going on inside them,” the therapist told me back then.

I have met two types of Western people. One type believes that the Soviet Union was actually not so bad, and the other that the horrors were confined to well-known Stalinist crimes and not much more. Both are wrong because they fail to understand what it takes to overcome a trauma larger than one’s life; the collective trauma of oppression, experienced as an individual and as a nation.

Taken all in all, grandma lived quite a successful life, in spite of it all. In Siberia, despite everything, she discovered that she enjoyed math and science. Years later, it was grandma who would bring prized oranges, which were difficult to get in the Soviet Union, from our capital Vilnius to her youngest siblings, a new generation born back in Lithuania.

Grandma died of cancer in March at the age of 83, on exactly the day that her husband had passed away six years earlier. It was late in the month, an exhausting month. Our relationship had completely soured due to some family drama and her passivity in that event, and we were not on speaking terms. I was refusing to take her calls, but I knew she was in pain. I am bad with people dying — I was just the same when my father went.

But as I listened to my mother’s short daily reports on her condition, I almost caught myself hoping she would die. I was hoping for this to happen, not because we were on poor terms, not even because I wanted her terrible pain to end. Quite the opposite – despite the anger I felt towards her, I was terrified to think she was seeing what I was seeing.

I didn’t want her to relive what she’d been through. I saw Russian tanks moving across borders, the bombing of Ukrainian hospitals, the ripples of misery moving across another country, and suddenly her trauma felt very real for me, too. I wasn’t scared for myself, I wasn’t terrified of the Russian-inflicted horror returning. This is simply in my blood; it’s a burden carried by every Lithuanian. Even my parents’ generation experienced death by Soviet tanks in 1991.

The last time we spoke, when she was already very sick with cancer, she told me of the guilt she felt for the dysfunction of her family. On February 24, 2022, I knew it was not her fault.

Saulė Kubiliūtė is a Lithuanian writer, interpreter, and translator.