The beginning of Hungary’s policy of greater openness towards China dates back to 2002-2003. Yet it was not until the global financial crisis in 2007 that the process gained significant momentum. The global economic crisis highlighted Hungary’s dependence on Western markets and capital, which contributed to five years of economic stagnation between 2007 and 2012, including a 2009 recession which saw a 6.7% fall in gross domestic product (GDP). The economic problems were compounded by political tensions between Hungary and the European Union (EU), which were mounting as a consequence of the efforts to create an “illiberal democracy.” Moreover, the Hungarians saw a chance in the rising power of the Chinese economy and institutions.

The policy of “opening to the East” (Keleti Nyitás), introduced at the beginning of 2010, was supposed to attract capital from China to counterbalance that from the EU. The first big greenfield investment in Hungary – Huawei’s logistics center for Europe and North Africa — was opened in 2009 as the first step in the diversification of Hungarian economy. However, despite a positive political climate, the policy of “opening” has brought only limited results.

Apart from the acquisition of the Wanhua-Borsod Chem chemical raw material manufacturing company in 2013 for €1.3 bn ($1.6 bn), there have been no similar, spectacular investments. Even so, according to the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS), the total value amounted to €2.4 billion ($2.9 bn) between 2010 and 2019, which is the highest among Central and East European (CEE) countries. Hungarian and Chinese authorities indicate an even higher value of around €4.1 bn ($5 bn).

The most recent flagship Chinese-Hungarian policy has been the deal to finance improvements in the railway from Budapest–Belgrade, a journey that currently takes more than eight hours and which could be cut by more than half. On 24 April 2020, a 20-year €1.5 bn ($1.8 bn) loan agreement was signed, approving finance for construction. The Chinese loan covers 85% of the project’s cost, while the remaining 15% is covered by Hungary. The railroad is planned to be 350 km (217 miles) long – 166 km (103 miles) of the tracks in Hungary and 184 km (114 miles) in Serbia. It is no coincidence that these two countries are involved – they are among China’s closest partners in China’s ambitious 17+1 format, and both have worked hard to strengthen economic cooperation with China. The venture has been heavily criticized by economists for its economic irrelevance, and the project’s details will be classified for 10 years, reinforcing the concerns about its political nature.

Hungary has also actively supported China’s so-called mask diplomacy. At the end of March 2020, Hungarian officials formally questioned the capability of the EU and the West to provide adequate aid, stating that China would be a better partner, Hungary being the only EU country to approve Chinese vaccines. Moreover, Orbán’s statement of support is a clear gesture of political friendship given the questionable efficacy of Chinese vaccines. Additionally, the government’s cooperative approach assists China’s to position itself as a major force in global health governance. Vaccine diplomacy, while endeavoring to improve the image of China worldwide, also reinforces domestic propaganda. Its primary goal is to strengthen the Communist Party’s authority by portraying China a global “helping hand”.

Cooperation in the field of education is also intense. On 16 December 2019, Hungarian Minister for Innovation and Technology, László Palkovics, and the President of Fudan University, Xu Ningsheng, signed an agreement in Shanghai to establish Fudan University’s first foreign campus, in Budapest. It is expected to be completed by 2024 and educate about 5,000-6,000 students, mainly in economics and management. The project is seen not only as an opportunity to raise the attractiveness of Hungarian higher education, but also as a way to build a network of contacts that will facilitate business cooperation.

Contrary to Hungary’s initial hopes, the partnership with China has not become a viable alternative to the West. The role of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in investment and trade remains limited – and a sudden change in this state of affairs is unlikely. In 2019 China accounted only for 1,48% of Hungary’s exports ($1,79 bn) and 6,15% of its imports ($7,06 bn), according to Observatory of Economic Complexity. Good political relations between Beijing and Budapest were not enough to attract massive inflows of Chinese capital which primarily concentrated in Western and Northern Europe.

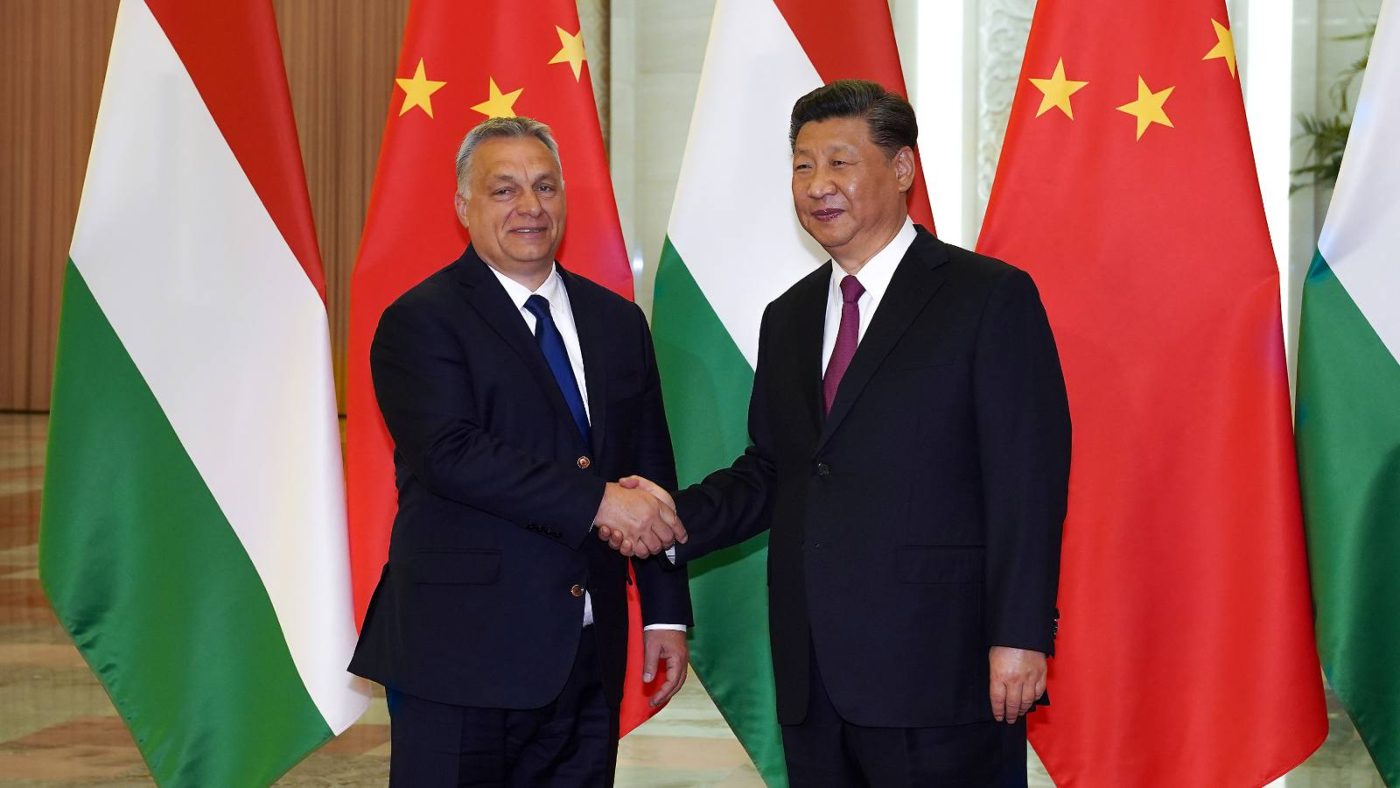

For Viktor Orbán’s government, China serves as an additional foreign policy pillar which helps to balance strained relations with the EU. Thanks to close ties with China and Russia, the Hungarian government can counter the narrative of diplomatic isolation among Western countries. And yet the Hungarian example provides a valuable lesson for other CEE countries, because it proves that even far-reaching political and moral compromises do not translate into real economic benefits, and that China is not currently a viable alternative to the European-American partnership.