We live in the age of counter-Enlightenment. What seemed like a collection of dispersed autocratic and simply illiberal states, has now coalesced into a fully blown ideological movement premised on not only resisting liberal internationalism on an ad hoc basis but exporting authoritarian models of governance.

Illiberalism’s flag-bearers in China and Russia have also shown they can harness modernity. What was deemed an asset peculiar to the West — because progress was considered a direct result of liberal norms and vice versa — is now being fitfully mastered by its enemies.

Yet the bad news comes with a good news rider. If the United States wants to maintain global influence, it cannot simply seek to maintain the old world order. The appearance of serious rivals with a hostile ideology will stiffen America’s resolve, as happened in the Second World War and in the Cold War. For the past decade or more, this ideological motivation has been lacking because China’s competition was mostly still viewed as fitting within the framework of the liberal world order. China, the West wrongly believed, could be lured into better behavior by the self-evident benefits of cooperation.

Westerners expected poor economic conditions to liberalize or even bring down the Chinese and Russian regimes, but the reality is quite different. China gathered strength after the 2008 financial crisis and raised its profile through vaccine diplomacy during the covid-19 pandemic. Russia, despite suffering extensive sanctions, is growing more assertive in the South Caucasus, Black Sea, and parts of the Middle East. Even in the case of Iran, its most active foreign involvement coincided with Western sanctions.

Illiberalism has been wrongly described as unstable and as a transitory stage in the evolution towards the liberal-democratic model. But armed with modern technology, it is resilient and resourceful, and is a much longer-term challenge than the crude communism of the past. Failure to deliver on its promises ultimately killed the communist dream, but failure to deliver in quasi-capitalist illiberal states will not bring down the order as quickly as some would think.

China and Russia’s example makes illiberalism fashionable among the struggling states of Europe and Asia. In Georgia, yet another far-right movement — Unity, Essence, Hope — was just created which repudiates the tenets of liberalism and advocates the reversal of the entire political system and what is more important, seeks closer ties with Russia. Their arguments are more nuanced though. Fearing a backlash, they explain the need to work with Russia from geopolitical necessity.

In Armenia, upcoming parliamentary elections will usher in closer ties with Moscow, regardless of which side wins. This will mean greater dependence on illiberal Russia which will likely include considerable backsliding in democratic reforms. After all, Russia has been uncomfortable with Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan’s overtly pro-democracy government since 2018.

In Ukraine, internal reforms have stalled, and corruption is still a country-wide challenge, while neighboring Moldova is notoriously divided.

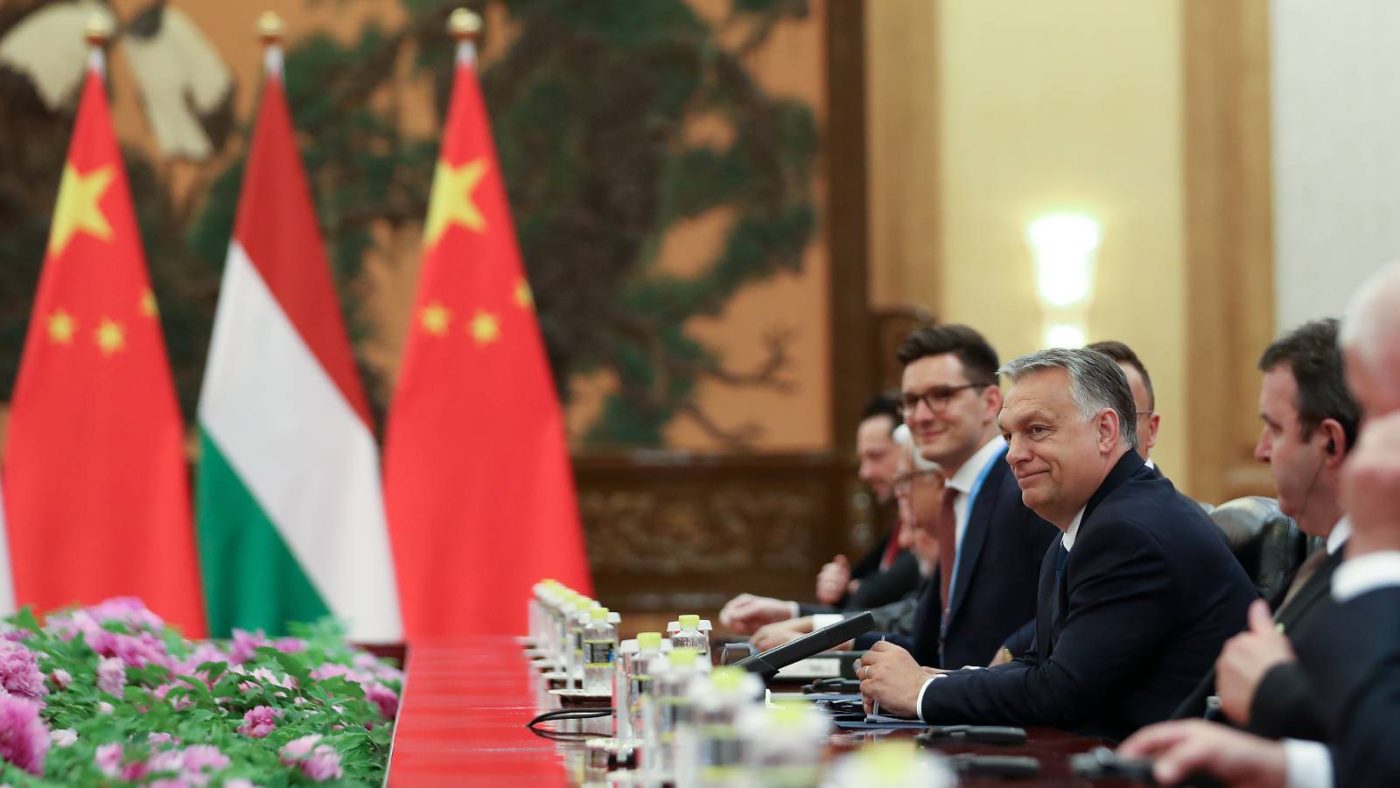

All these problems are abetted by Russia’s military presence on their sovereign territory and by troubled economies which create space for China’s strings-attached cash infusions. The governments in these post-Soviet states are manifesting the ability to appropriate the liberal concepts on state and economy to advance their illiberal agenda. Take Georgia or Armenia. Both hold elections, and are democracies to varying extents. But instead of ushering in political plurality and peaceful changes of government, these provide fertile ground for ruling governments to employ state power to entrench their positions. Both see accusations of alleged vote-rigging or the use of state finances to intimidate the opposition, a classic case of creeping illiberal practices under the guise of democracy. Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán boasted as early as 2014 that, “the new state that we are building is an illiberal state, a non-liberal state.”

The West has to look at this challenge from a wider historical perspective. Hopes for the eventual abandonment of the illiberal governing model are not self-fulfilling. Bolstering the liberal order by strengthening rules-based policies is one approach. Another is to show that liberalism is more attuned to economic and governance progress. The means to shore up state institutions in those fragile countries should be sought.

The West should support fragile the fragile states of Georgia, Ukraine, Moldova, and Armenia because there is still some hope they can take a better path. Recently Georgia’s politicians resolved a major political crisis by re-entering the legislature after months of boycotts. In Armenia, the decision to call snap parliamentary elections lowered political tensions. Illiberalism in the region — all Armenia’s and Georgia’s neighbors are less-than-liberal states — could easily engulf these tiny islands of liberal democracy.

Illiberalism is essentially a counter-Enlightenment and is seen by autocrats as a return to normalcy in human and state relations. They hail the primacy of state and strongman rule, or clique rule, and create something eerily reminiscent of illiberal governments between the two world wars, when smaller and newer European democratic systems were unable to survive pressures from within and without.

President Joe Biden’s insistence on upholding democratic and liberal ideals suggests the U.S. is willing to battle illiberalism. Whichever model prevails will ultimately define our world and will be decisive for smaller states bordering illiberal powers. Military power matters, but the battle for hearts and minds is just as important.

Emil Avdaliani is professor at European University and the director of Middle East Studies at Georgian think tank, Geocase.