A new Internet Iron Curtain is descending over Russia. The Kremlin has banned Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter as extremist organizations. Other companies such as Netflix and Spotify, faced with demands to host government propaganda, have left of their own volition.

YouTube, used by three quarters of Russian Internet users, is now the last Western platform standing – but probably not for long. Russia’s media regulator, Roskomnadzor, has stepped up threats, while Gazprom media, the state-owned subsidiary of the natural gas monopoly Gazprom, has proposed an alternative – RuTube.

The Kremlin’s assault on Western tech platforms underlines the critical role they play in the global fight for democracy and freedom. While these companies face fierce criticism in Europe and the US over everything from their market power to data privacy, they are often the only outlets for independent journalists, critical views, and human rights activists in repressive regimes. Democratic governments must stand up for freedom of expression, which means standing up for independent tech platforms too.

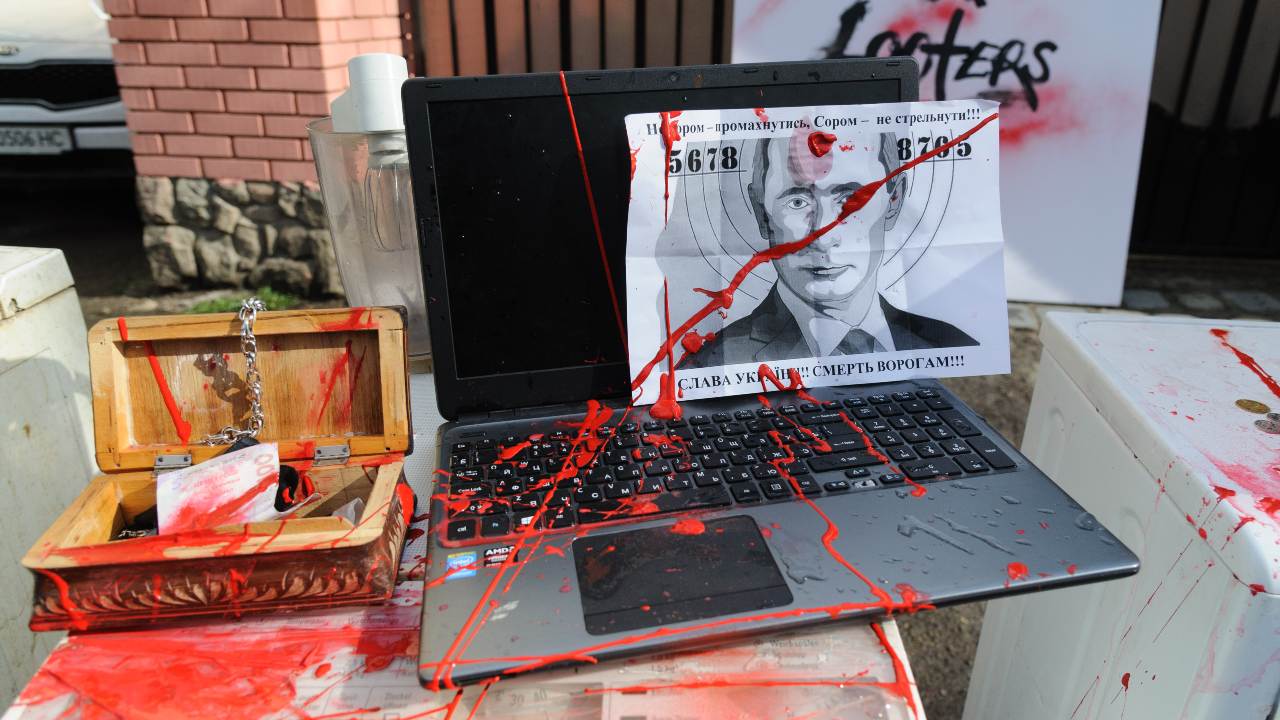

Ukraine’s success in the information war depends on free and open Internet access. At the beginning of the war, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy took out his iPhone to broadcast his courage to the world and to reassure his citizens that he was staying in Kyiv. Ordinary Ukrainians posted on Facebook and TikTok, documenting Russian war crimes. Thanks to tech, Ukraine is winning the global information war. And the Kremlin knows it: the Russian government banned an interview with President Zelenskyy and independent Russian journalists.

Not surprisingly, the free Internet has become a prime target for authoritarian leaders who see it as a threat to their rule. For years, the now-imprisoned Russian opposition leader, Alexei Navalny, savvily used YouTube to reach Russians across the country even as he was banned from mainstream Russian media. His documentary, Putin’s Palace, an exposé of a lavish palace in Crimea, garnered 100 million views in its first week online. Today, if YouTube goes the way of its peers, so will any remaining space in Russia for independent voices.

The Kremlin’s recent crackdown on social media has been long in the making. In 2018, the Russian government instituted a package of restrictive measures, the so-called Yarovaya law, requiring companies to store data on their users and provide access to that data to Russian authorities on-demand or be banned from operating in Russia.

Telegram, a popular Russian messaging app, refused to comply, leading to a digital cat-and-mouse chase between the app and government regulators. Eventually, Telegram regained its ability to operate in Russia, but the incident marked the beginning of a broad government campaign to go after non-state-controlled social media.

The Russian government has continued to build pressure. Western companies cannot reasonably meet difficult legal and technically impossible requirements. A ‘hostage-taking’ law passed in 2021 requires companies to maintain employees in Russia, prompting concerns of jailed employees if companies do not follow the will of the Kremlin.

Last fall, Google and Apple removed a voting tool associated with Navalny from their app stores, later revealing that Russian government agents had visited the homes of their employees. Around the same time, Twitter, after resisting demands to remove content, had its website traffic slowed to the point of non-functionality.

It is easy to understand why Russia views Western platforms as a threat. Without them, truthful information about the atrocities the Russian military is committing in Ukraine is easy to hide from Russian citizens, and opposition voices are silenced.

Unfortunately, Western governments have only tacitly acknowledged the problem. The US State Department made discrete references to Russia’s pressure tactics, while the EU generally condemned Russia’s campaign toward digital authoritarianism.

Instead, governments on both sides of the Atlantic have harangued “Big Tech” for being a threat to their own democracies. In the United States, the Department of Justice has endorsed congressional efforts to break up major technology firms. In the EU, leaders have agreed to major legislation that specifically targets large American technology companies for additional legal burdens. In some cases, this legislation may even aid Russia – for example, Russian social media could absorb information on Europeans through new interoperability requirements.

When Western platforms are expelled from countries where democracy is in decline, others, who have few qualms about complying with repressive laws, step in to fill the void. Russians will turn to domestic platforms like VKontakte and lower quality replacements, like RuTube or a new copycat Russian version of Instagram. Chinese state-sponsored apps, including TikTok, will gain market share.

In the global fight between democracy and authoritarianism, technology companies are caught in the middle. And policymakers may not be able to have it both ways – simultaneously claiming that “Big Tech” is destroying democracy while at the same time demanding that the companies should be beacons of democratic values.

Dr. Alina Polyakova is the President and CEO of the Center for European Policy Analysis.