Sailing close to the wind is a test of a seafarer’s skill. Sailing too close means that a ship’s sails are misaligned with the wind and course. Used metaphorically, it suggests risky choices.

Introduction

The Baltic Sea region1 is part of a wider landscape, ranging from the Arctic to the Black Sea, in which the United States and its allies are in an existential struggle against determined adversaries — a destructive Russian Federation and a rising China. Although it is hard to identify a period in recent history when national efforts and security ties were stronger in the Baltic Sea region, the West’s response to this reality has been fragmented and incomplete and remains inadequate given Russia’s military advantage in the region. At stake is not only the security of the countries concerned but also Europe’s peace and stability, and NATO’s credibility.

Even as the Biden administration seeks to reinvigorate U.S. engagement with Europe and NATO, challenges in the Indo-Pacific, economic issues, the fallout from the coronavirus pandemic, and nontraditional threats like climate change could take priority at the expense of progress on regional security. That would be a strategic mistake. As strategic competition between the transatlantic alliance and Russia and China intensifies, stronger regional and transatlantic efforts are needed to enhance defense and deterrence in this crucial region.

This study aims to forge a focused, forward-looking transatlantic security agenda for the Baltic Sea region. Part 1, which follows, offers an audit and assessment of security challenges, highlighting gaps in the alliance’s defense and deterrence in the Baltic Sea region. The research draws on dozens of interviews with current and former political and military decision-makers and experts, as well as policy workshops, existing literature, and original survey data. Part 2, to be published in the fall of 2021, will explore how to address these shortcomings, offer suggestions to maximize regional and collective defense efforts, and outline specific recommendations for the United States, NATO, and regional players.

Photo: Romanian Marines storm a beach on Saaremaa Island in Estonia during BALTOPS 2019. An annual US-led exercise involving 16 NATO Allies and two partner nations, BALTOPS focuses on improving maritime interoperability through multinational amphibious operations in the Baltic Sea region. Credit: NATO

The Strategic Context

The road to defeat is short for the Baltic Sea region and all the countries of the Euro-Atlantic community. If by military bluff, intimidation, or actual attack Russia can challenge NATO and U.S. regional security guarantees, it can upend the post-1991 security order in Europe in a matter of hours. Nothing else in Russia’s military toolbox offers such a prospect of speedy and decisive geopolitical victory.

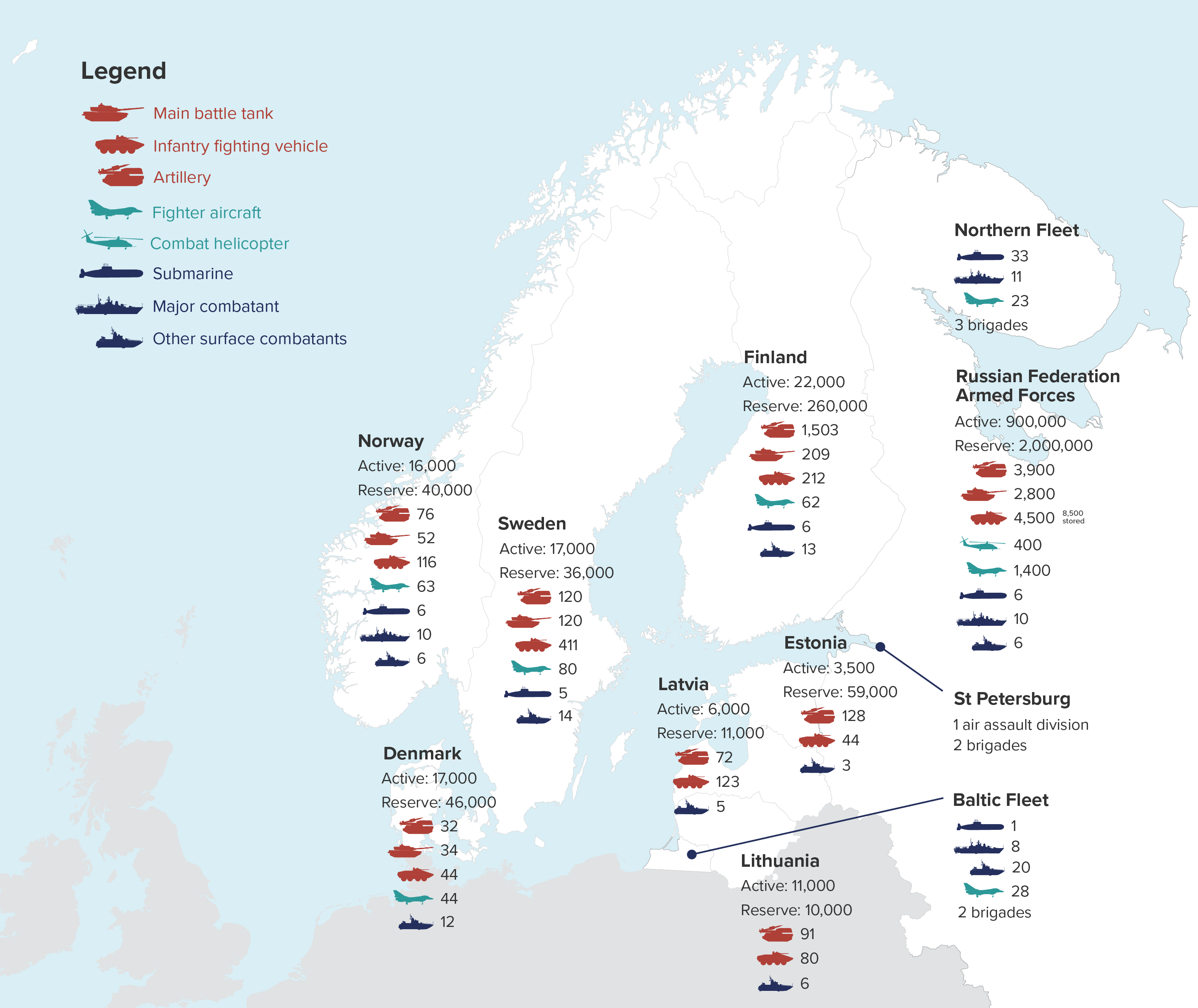

Still, many are complacent about the military danger from Russia. Since 2008, Russia has strengthened its quantitative and qualitative advantage in the Baltic Sea region and could potentially muster around 125,000 high-readiness ground forces in the region in 14 days. About one-third of the Russian armed forces are ready to operate within 24 hours to 72 hours, and the Kremlin has a proclivity for operating unexpectedly. Locally, Russia has “absolute supremacy” in terms of offensive equipment: tanks, fighter aircraft, and rocket artillery. In the past decade, it has also set up three army commands, five new division headquarters, and 15 new mechanized regiments in the Western Military District (MD). Zapad exercises exemplify Russia’s ability to rehearse large, combined operations, including live-fire and realistic, unscripted scenarios, and Russia’s dominance of the escalation ladder.

Source: “Finnish Military Intelligence Review 2021,” Finnish Defense Forces, 2021.

In the air, Russia has a local advantage as well, reinforced by extensive and advanced air-defense and electronic warfare (EW) capabilities. Russia has deployed new ground-based, intermediate-range nuclear-capable missiles in breach of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty and continues to conduct other activities that threaten Baltic Sea regional security, such as last year’s High Altitude Low Opening (HALO) commando parachute jumps in the Arctic. Russian planes and ships also conduct unsafe maneuvers and intrusions in the region, failing to indicate their position and altitude, file a flight plan, or communicate with controllers. There are unconfirmed reports of EW against U.S. Navy vessels in the Baltic Sea and the use of unmanned surveillance equipment launched from fishing vessels. From the Kremlin’s point of view, these activities are low-risk and effective, but they also significantly raise the possibility of accidents and dangerous miscalculations between Russia and NATO. These realities highlight Russia’s continued and growing readiness to win short wars and break Western political will.

The Kaliningrad exclave, which Russia strategically maintains in the region, presents challenges as well as opportunities. Countering Russia’s capabilities there would be a formidable challenge, not least because of the risk of escalation. Russia upgraded a nuclear weapons storage site in 2018, and the Iskander missiles deployed are nuclear-capable. Russia is also thought to have tactical (battlefield) nuclear weapons capabilities and 19 missile-armed corvettes that have since 2016 been fitted with eight vertically launched Kalibr cruise missiles. Kaliningrad is well-defended from any attempt to neutralize military assets with eight battalions of long-range S-300 and S-400 surface-to-air missile batteries as well as shorter-range systems. Still, Kaliningrad is surrounded by Polish and Lithuanian territory. While Russia’s anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) capabilities would have an impact on NATO’s mobility, these systems are not impregnable. Russia’s strategic nuclear installations on the Kola Peninsula also risk being targeted in the event of a conflict in the Baltic Sea region.

The central feature of Russia’s approach to the region is ambiguity. The Kremlin does not articulate a clear strategy or approach the region as a whole but targets individual countries through subthreshold or “hybrid” capabilities. These include the threatened or actual use of nuclear weapons at one extreme, and beneficial energy, trade, transit, and investment relationships to favored countries at the other. Russia dislikes the presence of outside NATO forces in the Baltic states and uses sophisticated and varied means, overt and covert, to hamper the Baltic states’ decision-making, corrode internal cohesion, alienate Western allies and partners, and increase anti-Western sentiment. It aims to prevent an increased NATO presence (infrastructure and deployment) and NATO membership or closer ties for Finland and Sweden, maintains and develops control and ownership of critical infrastructure, and counters the local historical narrative that depicts the Soviet and Nazi occupiers as equally reprehensible.

Map of Key Regional Alliances and Partnerships

Any Russian military or subthreshold action against the Baltic states or Poland would involve Belarus, which is the Kremlin’s closest ally and linked to Russia in a “Union State” (also known as the Russian-Belarusian Union). In March 2021, the two countries signed a five-year strategic partnership agreement on cooperation in air, airborne, air-defense, land, and special operations forces. Belarusian President Alyaksandr Lukashenka backed the stationing of Russian aircraft in Belarus, while the two countries’ defense ministers announced plans for three joint training centers. Air and missile systems are already highly integrated and under Russian control, and Russia could leave S-400 air-defense systems in place in Belarus after this year’s Zapad exercises. Belarusian intelligence operations are active and hostile in Lithuania, Latvia, and Poland. The Astravets nuclear power plant, on the border with Lithuania, risks distorting the region’s electricity market and has been plagued by safety, management, transparency, and regulatory failings.

China adds an extra dimension to the international security picture for the countries of the Baltic Sea region. China’s presence in the Baltic Sea region itself is limited, with several countries playing notable roles in resisting Chinese influence operations. China’s strongest ties in the region are with Belarus, where it has high-profile investments and supplies surveillance technology, although this relationship lacks depth. The Chinese navy conducted a high-profile visit to the Baltic Sea in 2017 for joint exercises with the Russian Baltic Fleet and is expected to take part in the Russian-led Zapad exercise this year, underlining the Sino-Russian security relationship. The most important influence of China in the Baltic Sea region, however, is the potential effect of a crisis in the Indo-Pacific region on U.S. resources and attention. A serious conflict over Taiwan, for example, could create a window of opportunity for the Kremlin to test NATO’s resolve in defending the Baltic states.

Photo: British soldier waits in the snow during cold weather training exercise in Estonia. Credit: NATO

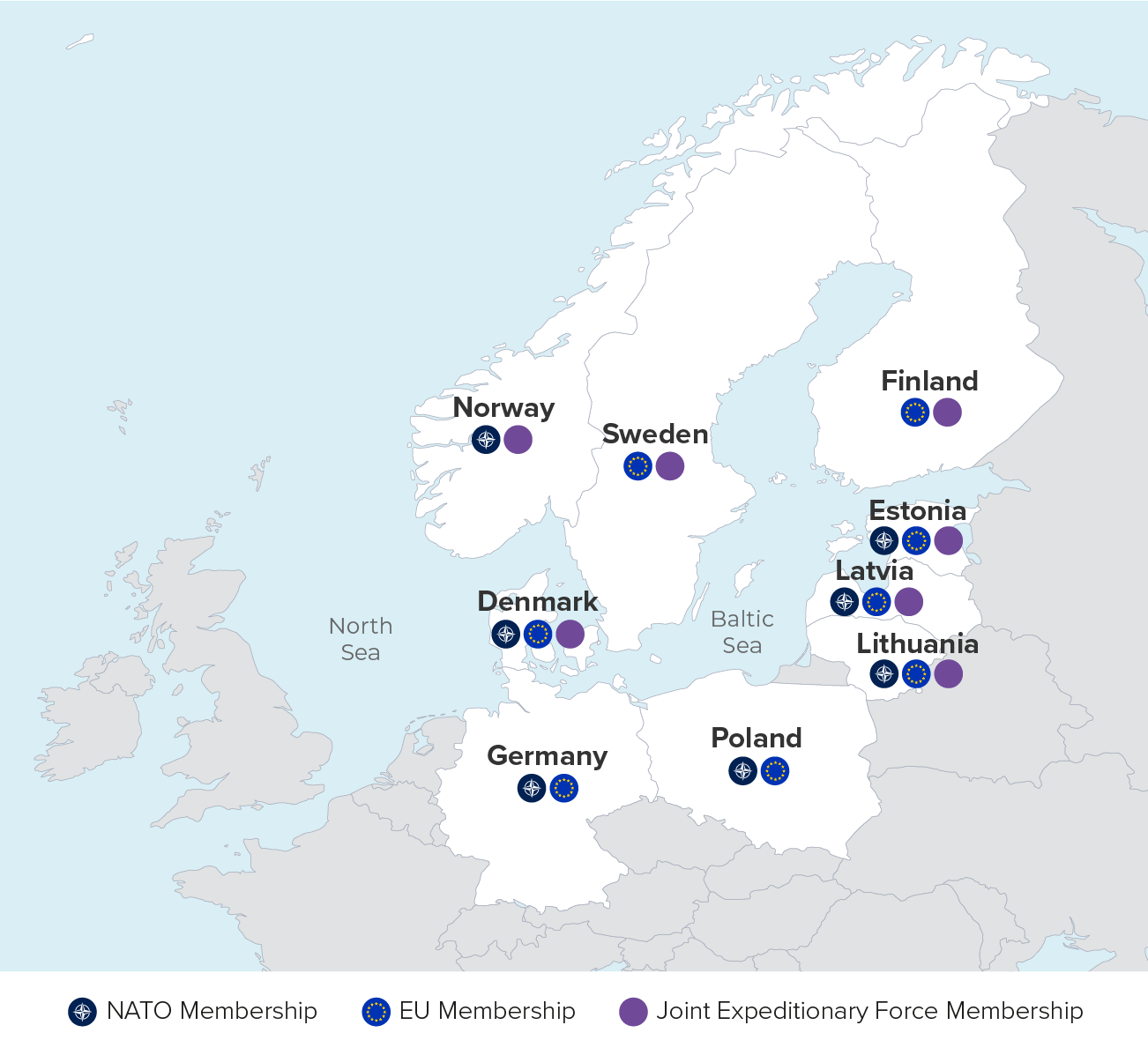

NATO has responded swiftly to these challenges in many ways. Its role in the region has transformed since 2014 with enhanced Forward Presence (eFP) in the Baltic states, Baltic Air Policing, two divisional and one corps headquarters in the region, and NATO Force Integration Units (NFIUs). Intelligence sharing, particularly of open-source material, has improved. The European Union’s (EU’s) defense cooperation with NATO has improved with the establishment of the Joint Support and Enabling Command (JSEC) headquarters in Ulm, Germany, to improve logistics and mobility, although most EU defense efforts have yet to be realized.

The scale and tempo of allied exercises has transformed in recent years, particularly involving Sweden and Finland. Cold Response 2022, involving 40,000 NATO troops from 10 countries, will be the largest military exercise inside Norway’s Arctic Circle since the 1980s. Exercises have yet to reach the level required — but combined with the increased national capabilities of countries in the region and the resources available from outside allies and partners, Russia can no longer disregard the risks to its own territory of any military adventures in the region.

The countries of the region have also reacted. In 2015, Poland and Estonia were the only two countries to meet NATO’s 2% of GDP defense-spending target. Now, Latvia and Lithuania do too, and so will Finland in 2021. Sweden will raise spending by 40% between 2021 and 2025 to around 1.5%, the biggest increase in 70 years. Denmark is raising spending to 1.5% by 2023. Poland plans to reach 2.5% by 2030. The biggest improvement in capabilities in the region has been the acquisition by Denmark, Norway, and Poland (as well as the Netherlands and the United Kingdom) of the F-35 Lightning II fighter, the only allied aircraft with the capability of penetrating Russia’s S-400 air defenses. Finland and Sweden have sharply strengthened their security cooperation, and their bilateral and trilateral ties with the United States.

The security balance in the region is inherently unstable: either NATO and its allies are secure and Russia is vulnerable, or vice versa. While the Baltic Sea region’s security faces a number of challenges and critical gaps, this does not mean that a Russian military attack is likely or imminent given the combination of national defenses, allied eFP forces, NATO’s credibility, and the vulnerability of Kaliningrad. But circumstances can change.

Photo: U.S. Special Forces fast-rope from Ospreys in Latvia. Credit: NATO

Key Findings

The security of the Baltic Sea region will continue to be determined by the climate of east-west relations and EU-NATO cohesion. Stronger regional cooperation would enable the countries of the Baltic Sea region to take greater responsibility for their own defense and deterrence. In the interim, there are still challenges to the Baltic Sea region’s defense and deterrence resulting from:

- Differing threat assessments, chiefly at a political level. Strategic thinking about the region is piecemeal: few have articulated a clear picture of a desired end state for regional security, and a common threat assessment is lacking. The approach in many countries is backward-looking: getting ready to fight the last war, not the next one. Many European NATO members, in particular, remain in a bubble of self-delusion regarding the nature of the threat faced by the alliance. None of the countries in the Baltic Sea region can, on their own, defend themselves nor are they capable of defending each other. The most vital factor in alliance credibility still is, therefore, the permanent or persistent presence of outside forces, coupled with continued focus by U.S. decision-makers on the region’s security. Russia realizes this and, therefore, seeks to distract and weaken Western alliances.

- Gaps in intelligence collection, sharing, and fusion. NATO has the intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities to gain a fuller military picture of the air, surface, and sub-surface domains. But these capabilities are fragile, fragmented, and spasmodic in all domains. The countries of the region need an “unblinking eye” that encompasses air, sea, land, and cyber domains, and that analyzes and acts on what it sees. But the Baltic states which most need ISR capabilities are the least able to afford them. The credibility of eFP battle groups suffers from the lack of combat service support units including ISR capabilities, artillery, engineers, logistics, and ground-based air defense.

- Lack of trust among some regional countries. A CEPA survey of regional security experts shows the greatest level of perceived trust between Finland and Sweden and the lowest between Poland and Sweden, with significant variation among other regional players. The trust deficit between the countries of the region is of strategic importance, as it currently inhibits deeper cooperation.

- Divergent economic interests. Within the region, national defense spending is rising. But fragmented acquisition programs, domestic political considerations, and bureaucratic friction mean that the region’s huge collective defense budget often fails to deliver the results it could and should. Simultaneously, the Kremlin uses economic sanctions, such as import curbs and restrictions on exports and transit, to manipulate and divide regional allies and partners on economic grounds, often balancing aggressive behavior with charm offensives elsewhere. It seeks to secure a strong economic relationship with Germany, exemplified by the Nord Stream natural gas pipelines, which exacerbates disagreements among regional allies on how to approach Russia and undermines allied cohesion.

- Differences and shortcomings in air and maritime strategies. Since the end of the Cold War, military emphasis has been on land-based defense and deterrence. The main aviation element is the Baltic Air Policing mission, although the visiting aircraft are essentially a symbolic presence. Any effort in the air would involve Swedish and Finnish cooperation, heavy U.S. involvement, and countering Russia’s formidable air-defense capabilities. The maritime picture is no better and the status quo favors Russia. Absent substantial outside involvement, Russia’s Baltic Fleet could harass sea traffic and mount surprise attacks or support subthreshold operations. With the exception of Poland’s coastal batteries, the Baltic states and Poland’s naval efforts are largely limited to mine-hunting. Exercises are also insufficient. The main regional effort since 2009 has been the Sea Surveillance Cooperation Baltic Sea (SUCBAS) to maintain a Common Operational Picture (COP). The three Baltic states also exchange real-time unclassified Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA) information and are developing their Naval Vision 2030+ strategy.

Map of regional Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities

- Limitations on military mobility. NATO’s chief concern and greatest weakness has been and continues to be the availability of capable land forces on the European continent that can rapidly support and reinforce allies in the east in a crisis. The aspirations of the Readiness Action Plan (RAP) launched in 2014, the 2016 Warsaw Summit, and 2018 Readiness Initiative have not been fully implemented. Credible, well-rehearsed reinforcement plans are vital but lacking. The “Notice to Move” and “Notice to Effect” times of NATO’s higher readiness forces need reexamination.

- Inadequate Air and Missile Defense (AMD). The most important weapons systems — such as Air and Missile Defense (AMD) — are unaffordable for the countries that most need them, although Lithuania has purchased a mid-range AMD system and Norway is upgrading its own. Poland is the first U.S. ally to acquire the most modern Patriot (AMD) system, but only one Patriot system is deployed to protect U.S. forces in Europe.

- Multiple non-synchronized command structures. NATO’s command and force structures reflect historical and political priorities. The operational and strategic roles of the different headquarters involved in the Baltic Sea region are unclear. Generally, command and control systems in the region are untested. The chain of command between these headquarters and who would command joint operations in the Baltic Sea region, if needed, is unclear.

- Lack of realistic “hard” exercises. The lack of realistic exercises is a serious shortcoming for the security of Baltic Sea region. Large NATO exercises are carefully scripted, with orders, terrain, and participants worked out months, even years, in advance. This is a formula for defeat. Real war involves elements such as surprise and getting to grips with unfamiliar terrain and unforeseen obstacles. These need to be exercised too. To change this culture, political leaders need to protect their military commanders when things go wrong due to “friction” or “enemy action.”

- Fragmented security cooperation. There are limitations to regional security formats, such as the Nordic Defense Cooperation (NORDEFCO) and the Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF), so the Baltic countries remain dependent on outside help to defend and deter. But there are also limitations to what can be expected from the U.K., France, and Germany. Germany has neither the intention nor the ability to be the main security guarantor for the Baltic Sea region, France is a major European military power but stretched by commitments elsewhere and political uncertainties, and the U.K.’s ambitious defense aspirations are not matched by resources. Poland, the region’s military heavyweight, could probably muster two divisions in 10 days — a potent counterweight to Russian aggression — and is contributing heavily to military mobility. The planned Solidarity Transport Hub (STH) international airport, centrally located between ?ód? and Warsaw, will be capable of receiving heavy-lift aircraft and linked to rail and road upgrades.

- Overreliance on the United States as the linchpin of regional security. In many cases, the answer to the hardest questions is an assumption, stated or unstated, that the United States will fill the gap with the nuclear guarantee and multinational land-based, “tripwire” eFP forces. S.-led efforts have improved munitions and other stockpiles in Poland and the Baltic states, contribute bilaterally and multilaterally, and continuously deploy between 4,500 and 6,000 rotational troops in Poland. U.S. Special Forces can deploy quickly and unilaterally to the region, but most other elements require multilateral decision-making. The biggest gap in the U.S. presence is AMD with just one Patriot battalion deployed in Europe. Expecting the United States to carry too much of the burden for too long risks exhausting U.S. patience and tempting adversaries to test the U.S. commitment to defend the Baltic Sea region. As strategic attention in Washington shifts to the Indo-Pacific region, it would be rash for European allies to expect that under future administrations business will necessarily continue as usual.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge debts of gratitude to our CEPA colleagues, retired Col. Ray Wojcik, Dalia Bankauskait?, and retired Adm. Jamie Foggo, and to the International Institute for Strategic Studies for providing us with data from the 2021 edition of the invaluable compendium “The Military Balance.” This report also benefitted from exceptional research from FOI (the Swedish Defence Research Agency), the Center for Naval Analyses, and RAND Corporation.2

Our research draws on dozens of interviews, mostly conducted in the first quarter of 2021, with government officials, politicians, serving military officers, retired decision-makers, analysts, and other interested parties. To encourage frankness, we made it clear that their identities will not be disclosed and their contributions to our thinking are unattributable. We are grateful to the dozens of outside reviewers who have contributed thoughts on a draft version of this report.

Our work also benefits from other work by CEPA. This report’s predecessor, “The Coming Storm” (2015), noted the Russian threat and the strategic incoherence of the Baltic Sea region.3 It argued for postponing the question of Swedish and Finnish NATO membership and concentrating on building national capabilities and regional defense cooperation.

The 2018 report “Securing the Suwa?ki Corridor” highlighted the vulnerability of the land link between Poland and Lithuania.4 It analyzed Russia’s potential strategies and capabilities, the corridor’s history and terrain, NATO’s force posture, and the political and military environment surrounding the region. It recommended that NATO improve its defense and deterrence by ensuring its ability to quickly recognize threats, to increase its speed of decision-making, and to accelerate the movement of reinforcements across operational lines and national borders.

“One Flank, One Threat, One Presence” (2020) outlined NATO’s strategic incoherence on its eastern borders.5 It recommended that NATO enhance its role in the wider Black Sea region in all domains — strengthening deterrence and defense capabilities, improving ISR (see box on “ISR: Lessons from the Black Sea”), and adopting a common threat assessment to enable the rapid political and military reactions necessary to deter Russian probing and aggression.

The Military Mobility Project reports (2021) focused on five different political-military scenarios, including reinforcing Estonia from Norway, and the Baltic states through the Suwa?ki corridor.6 This project highlighted necessary changes to legal and regulatory standards, infrastructure, military requirements, and risk management needed to improve military mobility across Europe.

This project was conducted with the generous support of General Atomics Aeronautical Systems and the Ministry of Defense of Estonia. CEPA thanks both of these partners for their continued support of this critical research.

- This interim report deals chiefly with the defense and security problems of Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway, Poland, and Sweden, which we describe for convenience as the “Baltic Sea region.” These are the countries at most direct risk of attack from Russia. Germany, though a littoral Baltic Sea country, by virtue of its size and history plays a different role. Though these eight countries are all independent nation-states, they are — from a military point of view — a single operational environment. Iceland, though part of Nordic Defense Cooperation (NORDEFCO), plays little direct role in Baltic Sea regional security. The Nordic region comprises Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden. The “Baltics” or “Baltic states” or “Baltic region” comprises Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. The Nordic-Baltic region comprises the five Nordic and three Baltic countries. [↩]

- See: “Defence efforts in Northern Europe should focus on the near term,” Swedish Defense Research Agency, March 11, 2021, https://www.foi.se/en/foi/news-and-pressroom/news/2021-03-11-defence-efforts-in-northern-europe-should-focus-on-the-near-term.html. The most recent and definitive study of national capabilities in the region is by Sweden’s FOI. The authors note that individual countries have begun (but not completed) a political and military transformation that reflects the new security situation. Though the quality of forces, logistics, and Host Nation Support (HNS) have improved, FOI notes no significant improvement in the availability of forces since its previous report in 2017. See: Eva Hagström Frisell, Krister Pallin, Johan Engvall, Robert Dalsjö, Jakob Gustafsson, Albin Aronsson, Michael Jonsson, Björn Ottosson, Viktor Lundquist, Diana Lepp, Anna Sundberg, and Bengt-Göran Bergstrand, “Western Military Capability in Northern Europe 2020: Part II: National Capabilities,” Swedish Defence Research Agency, March 10, 2021, https://www.foi.se/report-summary?reportNo=FOI-R–5013–SE. A report by CNA notes that the highest density of Russia’s most capable ground and air forces is in its Western Military District (MD). Between 2013 and 2019 these forces underwent deep structural and organizational reforms and are now Russia’s most robust, most numerous, and most capable fighting forces. The report continues: “though the defense of the homeland seems to be the primary mission, forces in the Western MD have a plethora of capabilities to engage in offensive operations in Russia’s neighborhood and quickly deliver a preponderance of power to deliver a swift victory.” See: Konrad Muzyka, “Russian Forces in the Western Military District,” Center for Naval Analysis, 2020, https://www.cna.org/CNA_files/PDF/IOP-2020-U-028759-Final.pdf. A RAND Corporation report in 2018 noted the quality of Russian forces over the last decade has improved, with growing numbers of volunteer soldiers and modernized weapons, improvements to readiness, and experience gained from large-scale exercises and combat operations in Ukraine and Syria. It concludes that Russia’s demonstrated ability to mass ready forces from elsewhere within its borders, leveraging its internal rail and road networks, “gives Russian forces an important advantage in conflicts between mechanized forces close to their border.” See: Scott Boston, Michael Johnson, Nathan Beauchamp-Mustafaga, and Yvonne K. Crane, “Assessing the Conventional Force Imbalance in Europe: Implications for Countering Russian Local Superiority,” RAND Corporation, 2018, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2402.html. [↩]

- Edward Lucas, “The Coming Storm: Baltic Sea Security Report,” CEPA, June 2015, https://cepa.org/cepa_files/2015-CEPA-report-The_Coming_Storm.pdf. [↩]

- LTG (Ret.) Ben Hodges, Janusz Bugajski, and Peter B. Doran, “Securing the Suwa?ki Corridor: Strategy, Statecraft, Deterrence, and Defense,” CEPA, July 9, 2018, https://cepa.org/securing-the-suwalki-corridor/. [↩]

- LTG (Ret.) Ben Hodges, Janusz Bugajski, COL (Ret.) Ray Wojcik, and Carsten Schmiedl, “One Flank, One Threat, One Presence: A Strategy for NATO’s Eastern Flank,” CEPA, May 26, 2020, https://cepa.org/one-flank-one-threat-one-presence/. [↩]

- LTG (Ret.) Heinrich Brauss, LTG (Ret.) Ben Hodges, and Prof. Dr. Julian Lindley-French, “The CEPA Military Mobility Project: Moving Mountains for Europe’s Defense,” CEPA, March 3, 2021, https://cepa.org/the-cepa-military-mobility-project-moving-mountains-for-europes-defense/. [↩]