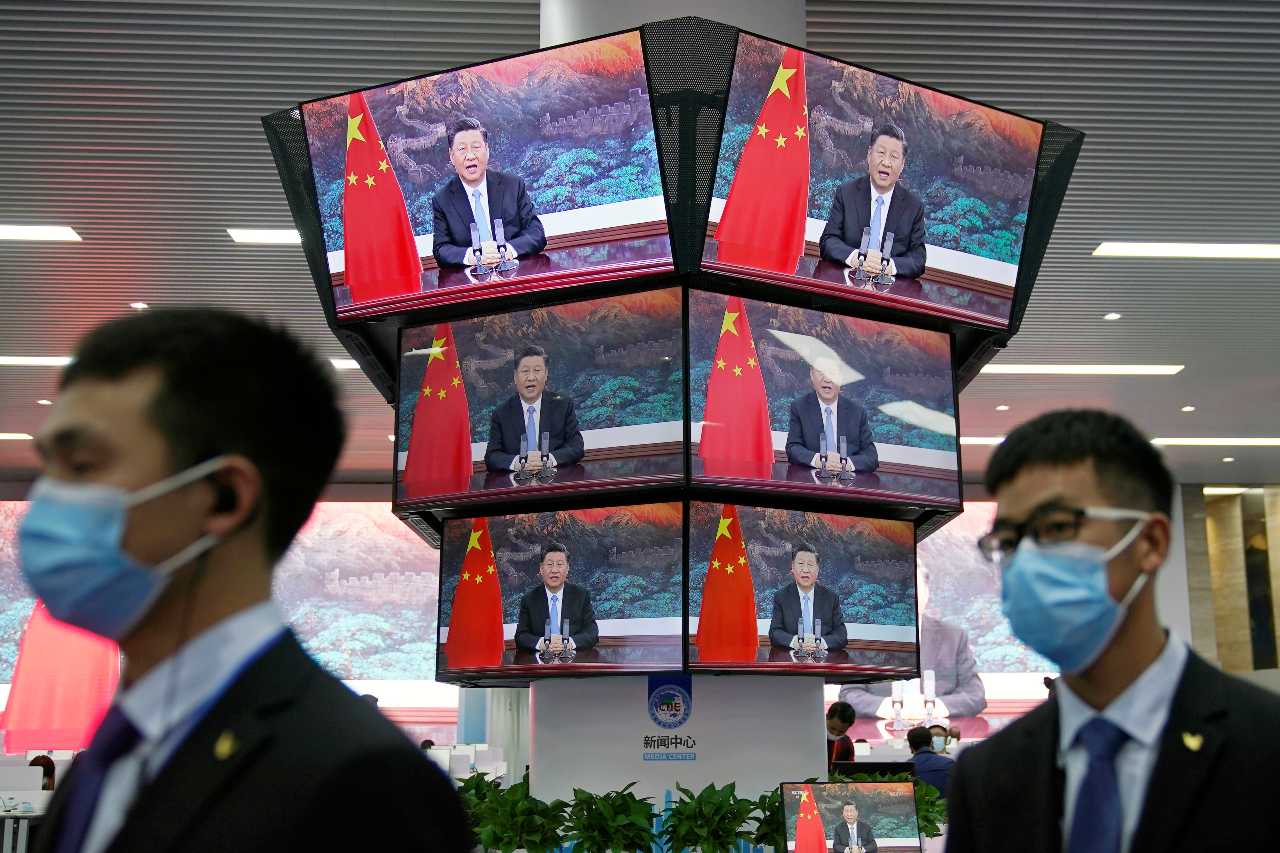

2022 is heavy with significance for Xi Jinping. Every five years, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) meets to ratify major personnel and policy decisions. The 20th Party Congress, which gathers in the fall, will rubber stamp Xi’s fate, whatever that may be.

For many months, Wei Jingsheng, China’s most famous dissident and a discerning analyst of CCP politics, was the only one who saw troubles ahead for Xi, while just about all other commentators predicted a certain third term.

His lone voice is now being joined by others. Wang Dan, who topped China’s “21 most wanted” list of student leaders and dissidents after the 1989 Tiananmen massacre, has noticed that the May 27 meeting of the Standing Committee of the Politburo was “strange”, and indicated dissent at the highest levels about Covid policy; while Wu Guoguang, a former People’s Republic of China (PRC) government official now in exile, has cautiously but extensively detailed Xi’s travails.

Yan Jiaqi, the former PRC government advisor who created the policy of “no lifetime tenure” for top leaders, which was enshrined in the 1982 PRC constitution, long ago issued warnings about the crisis to come in 2022, which Su Xiaokang, the author of “River Elegy” had recorded in November 2017, and recently reposted.

Prominent Westerners have also joined in. George Soros, the billionaire financier whose engagement with the PRC dates back to 1979, has said that Xi may not get a third term. Kevin Rudd, the former prime minister of Australia, long associated with the pro-engagement democrats, has meanwhile written op-eds in mainstream Western media and given speeches in elite forums pointedly critical of Xi Even Jacinda Ardern, the Prime Minister of New Zealand, which has long been dependent on China for its exports and had previously fought shy of expanded Western action against the Communist regime, joined the US President Joe Biden in a statement criticizing Xi’s policies on Xinjiang, Hong Kong, and Taiwan on June 1. (China responded with its standard rage rhetoric.)

Open opposition to Xi Jinping within China is rare, perhaps even astounding, but it has been underway for some time now. Fang Zhou, likely a pseudonym for an anti-Xi faction, offered blistering criticism of Xi at the start of the year. Hu Wei, a PRC government policy analyst whose article on the Russo-Ukrainian War and China’s Choice was widely circulated for its uninhibited attack on China’s Ukraine policy. Wang Xiangwei, a columnist for the South China Morning Post in Hong Kong, offers regular criticisms of Xi. All these men are writing within China and it is notable that they have not yet been arrested, which points to protection from behind the scenes.

Wang Jisi, the PRC’s foremost handler of Americans, on a mission to Washington in March to meet high-level Biden administration officials, offered non-public criticisms of Xi. Liu He, the party princeling seen following behind Xi with a pained look on his face, has opposed some of Xi’s economic policies amidst a sharp economic downturn. Li Keqiang, the Premier, has emerged as a strong critic of the Zero Covid policy’s impact on the economy.

Meanwhile, videos of harsh measures to enforce the Zero Covid policy and vehement complaints about the price paid by ordinary citizens are daily occurrences on Chinese social media in Shanghai. That lockdown was finally lifted on May 31.

So what’s going on?

While most outsiders will focus on the Party Congress in the fall, the real decision-making conclave is the annual August get-together of the CCP elders and high-level party officials at the beautiful beachside resort of Beidaihe. Although the CCP elders, who wield enormous power over appointments, are kept far from the masses they are purported to represent, they are not immune to public opinion. Hence the intense debate and criticisms leading up to this late-summer retreat.

It also has something to do with the norms of political succession (which the veteran China analyst Alice Miller famously called “institutionalization,”) whereby power resides with the CCP elders, the so called Eight Immortals, something foisted on Deng Xiaoping after the June 4, 1989, Tiananmen Massacre. It is a very Chinese communist setup — the country’s hereditary party elite is composed of 100 sons nominated for a political career; the General Secretary gets two five-year terms (a limit imposed on the unwilling Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao;) retirement at the appropriate age, (68) and a conclave of chosen elders who pick the next man for the top job.

Yan Jiaqi said on May 20 that three elders — Zhu Rongji, Zeng Qinghong, and Hu Jintao, have the authority (權威) to decide Xi’s fate. Wei Jingsheng added that the elders would weigh the decision based on a single factor — Xi’s ability to lengthen or shorten the CCP’s reign. If they decided on the latter, Xi is done.

If the norm holds (though bear in mind that Xi has already succeeded in altering the 1982 constitution forbidding life terms,) then former President Hu Jintao would make the decision on who replaces Xi. Hu Jintao is no pussycat — his removal of Politburo member, minister, and communist princeling, Bo Xilai, in 2013 was deft and efficient.

This system of personnel placement has nothing to do with government institutions, but it is part of the premodern (Leninist) arrangement of power among the CCP elite, most of whom hold no government position. One may disagree with Roger Garside’s China Coup in predictive details of the future overthrow of the regime, but it is no fantasy; it displays a keen understanding of the premodern organization of power among the CCP elite.

In short, this is a time of flux. It may not appear so on the surface, but there is a great deal happening behind the scenes. What happens after the 20th Party Congress of course depends on who emerges victorious.

The open question is: Will Xi be “normed” out by the elders in Beidaihe this August? We simply don’t know enough to tell, but Xi’s ability to break the norm isn’t a foregone conclusion. His smug story that China dealt with Covid better than its Western counterparts has been humiliatingly revealed as a lie, as a rolling series of outbreaks of the virus has spread across the country. China’s much-touted science sector meanwhile failed to produce a vaccine anything as effective as those in the West. Not every senior communist will be amused by this.

The salient question is: What will Xi do in the next few months to ensure that he succeeds in holding onto power?

The two major moves that Xi has made this year — supporting Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in a joint effort to challenge the West, and Zero Covid to control the troublesome cities — have not gone well. Since Xi must appear infallible, he has dug in his heels in support of Putin, but his Zero Covid policy, already expanded to 45 cities, has gotten a strong pushback, especially in Shanghai.

What else might he do?

Since he controls both the security and propaganda apparatuses, he could try to prevent the elders from meeting each other at Beidaihe, which is what he apparently did last August. This year, however, the stakes are much higher. The elders have more incentives to evade Xi’s security details, communicating through their children, private secretaries, and their own ever-present security guards. Short of overpowering the elders with force, there isn’t much Xi could do. To do so would risk a far bigger crisis.

More likely, China’s leader will try to impress the elders with some foreign policy successes.

That may mean more summits, especially with the Europeans, better to convince the elders that he is skilled at handling foreigners, a prerequisite for the top job. (The last one, in April, went very badly indeed; Europeans were unimpressed by China’s support for Russia’s war of aggression on Ukraine.)

The rapid seizure of one or more of Taiwan’s outlying islands, while the world has its focus on Ukraine, is more likely. This would mark a statement of future intent for a full-scale invasion when Xi gets his third term.

So what can the democracies do?

- Continue to douse Xi and his brutal, expansionist regime in criticism

- Offer larger media platforms to Xi’s critics

- Ensure he is denied high-profile summit meetings before August

- Help Taiwan to build formidable defenses on its outlying islands so that rapid conquest is impossible, and

- Prepare a new package of sanctions with real teeth and rapidly arm Taiwan with additional modern weaponry.

Dimon Liu was born in China and fled at the outset of the Cultural Revolution. An independent commentator, she has written for the Asian Wall Street Journal and numerous other publications.