EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- Since the start of Hungary’s Eastern Opening policy under Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, and China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and 16+1 Initiative under President Xi Jinping, Hungary-China economic and political ties have grown increasingly strong.

- China’s relationship with Hungary and presence in the central and eastern European (CEE) region (e.g., Huawei tech, the Belgrade-to-Budapest railway, etc.) has raised unity and security concerns for the transatlantic alliance as it seeks to counter China.

- Despite suggestions by some journalists and academic experts that Hungary serves as China’s “Trojan horse,” the threat of direct Chinese influence on Hungarian or EU foreign policy is minimal. Nevertheless, the Sino-Hungarian relationship poses several challenges for the transatlantic alliance:

- First, it emboldens Orbán and sows greater ideological and policy division within the EU, making a united Western response to China more difficult.

- Second, BRI and the relationship exposes the US’s inability to establish a strong economic presence in the CEE region to compete with China. The relationship also puts into relief the US’s lack of technology leadership in developing infrastructure and telecommunications networks in the region.

- Addressing the first challenge requires that the transatlantic alliance:

- (1) Reduce Hungary-transatlantic alliance policy division vis-à-vis China. This involves pressuring Orbán at the highest levels of the US and German governments using economic and diplomatic leverage to align Hungary with Western foreign policy toward China — beginning with the issues of Huawei and the Belgrade-to-Budapest railway. Leverage may include making trade, debt relief, and active diplomatic ties conditional upon a change in Hungary’s policy.

- (2) Develop joint EU-US strategies to counter China whether or not Hungary aligns itself with the transatlantic alliance. This involves diplomatically and financially supporting the Three Seas Initiative (3SI), and further discussing and developing major trade entities such as the Trade and Technology Council (TTC) and a “TTIP 2.0.”

- Addressing the second challenge requires that the US:

- (3) Cultivate stronger business ties with CEE countries and private Hungarian businesses to establish a stronger technology presence in the region. This involves investing in and leveraging financial tools and programs such as the US Export-Import Bank, the Blue Dot Network, and the Build Back Better World (B3W).

INTRODUCTION

In April 2021, Hungary blocked an EU (European Union) statement condemning China for its authoritarian Hong Kong security law, its latest in a series of efforts shielding the Chinese regime from criticism.1 The backlash from the EU and its largest member, Germany, was fierce. German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas called Hungary’s move an “absolutely incomprehensible” action that prevented the EU from speaking with “one voice” over China.2 “This is not the first time that Hungary has broken away from [the EU’s] unity when it comes to the issue of China,” Maas said.2 Nor will it likely be the last.

Since Prime Minister Viktor Orbán came to power in 2010 and Hungary joined the 16+1 Initiative in 2012 and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013, China has become an important factor in Hungary-EU relations. Western claims that Hungary was or is becoming a Chinese “puppet”3 or “Trojan horse”4 that could damage the EU’s unity from within have become commonplace; they are often fueled by incidents such as the blocked EU statement and Orbán’s insistence on treating China as a partner and ally rather than as a competitor and rival. Hungary’s technological dealings with China also actively concern the US; Hungary’s use of China’s Huawei tech despite US pressure has especially been a source of tension between the two governments.5

In short, Budapest’s relations with Beijing, especially with regard to the BRI, have heightened tensions with the US, the EU, and within Hungary itself. Ultimately, how the transatlantic alliance finds itself challenged by the Sino-Hungarian relationship informs how the US and EU choose to respond. This report therefore seeks to answer the following questions:

In what ways does Hungary’s political-economic relationship with China impact the transatlantic alliance as it seeks to counter China? How can and should the US respond to these concerns, if at all?

To address these questions, the remainder of this report proceeds as follows. Section 2 describes Hungary’s relationship with the EU and the US. Section 3 explains how the Hungary-China relationship concerns the transatlantic alliance. Section 4 explains the nature of and dispels myths about Hungary’s relationship with China and describes the driving force behind the relationship. Section 5 discusses policy options and proposes a set of policy solutions. Section 5 concludes.

HUNGARY AND THE TRANSATLANTIC ALLIANCE

With the end of the Cold War and Hungary’s acceptance into NATO and the EU in 1999 and 2004 respectively, Hungary became a welcomed and involved member of the transatlantic community. Since Orbán came to power in 2010, however, Hungary’s relationships with the EU and the US have been tense, with China becoming a particular irritant in recent years.

HUNGARY-EU

The Hungary-EU relationship has proved politically tense but economically strong over the past decade, with both Hungarian domestic politics and foreign policy toward undemocratic states such as China playing an important role.

Since 2010, EU member Hungary has touted itself domestically as an “illiberal democracy”6 and a one-party state at the heart of Europe, distancing itself from its “traditional [European] democratic allies,”7 and drawing closer to other, non-European regimes such as China, Russia, and Turkey.8 Claiming it has systematically failed to comply with EU norms, policies, and expectations such as protecting the rule of law and standing for democracy,9 the EU has criticized Hungary for behaving like a “rogue state”7 within Europe. Hungary has flatly denied all accusations of wrongdoing, calling the EU a “liberal empire”7 and claiming it abuses its power, targets the state, and unjustly meddles in its domestic affairs.10

Driven by Orbán, Hungary’s conflict with the EU has become especially acute. Elected in 2010, Orbán has gradually “align[ed] the judicial, executive and legislative branches”11 in favor of his national-conservative, right-wing Fidesz party, effectively turning Hungary into a one-party state.7

In September 2018, the tension between Hungary and the EU worsened when the European Parliament voted to trigger Article 7 of the Treaty on the European Union, an action that could ultimately threaten Hungary’s EU funding and voting rights.6

This past year, they have further clashed or diverged on several foreign policy issues, with China most recently taking center stage. For instance, as internal strife began in Belarus following the (still) disputed results of the August 2021 presidential election, Orbán’s Hungary, which shares Aliaksandr Lukashenka’s authoritarian tendencies,12 called simply for dialogue with Belarus as the rest of the EU called for diplomatic or economic coercion.13 Later, in November 2020, Hungary blocked the EU budget including a COVID-19 relief package, objecting to a provision that would make funds contingent upon a country’s respect for democratic norms.14 Most recently, Hungary blocked or refused to sign several EU statements criticizing China for its actions related to Hong Kong and the South China Sea, and atrocities against the Uyghurs.15

This political tension has not led to economic friction, let alone a decoupling of their economies. Indeed, despite Hungary’s Opening to the East Strategy of cultivating economic links with China through 16+1 and BRI, Hungary-EU economic ties remain significant. For instance, Hungary continues to receive over €4bn ($4.6bn) from the EU per year, while contributing less than €1bn ($1.16bn) to the EU budget,16 making it the fourth-largest net recipient of EU funding.17

The EU also is Hungary’s largest economic partner, with 82% of its exports going to EU member states and 75% of its imports coming from within the EU.16 Eight of its 10 top importers and nine of its 10 top exporters are EU members (the UK is its tenth importer, Russia is its ninth exporter, and China is its third exporter).18 Germany, its top trading partner both for imports (25.3%) and exports (27.7%),18 is particularly important to Hungary, leading to a largely positive relationship that Hungary has come to depend on.19 Berlin therefore holds a level of economic and political leverage over Budapest that few, if any, other countries share.20

HUNGARY-US

The US-Hungary relationship has also weathered some tension over the past decade, some related to domestic Hungarian affairs and others to China (see Figure 2).

As Hungary trended toward authoritarianism, the US, led by President Barack Obama — a self-described champion of democracy, liberalism, and the rule of law — gave Orbán the cold shoulder, effectively cutting off high-level contacts.21 With Hungary’s interest in political recognition secondary to its desire for national security that the US — and not the EU — could offer through NATO, such lack of American appreciation, though problematic, would not generate outright anti-Americanism. Additionally, Orbán said in 2016 that “economic relations… [remained] good” during this period.22 This tame response reflects Hungary’s inherent dependence on the US and a respect for its power.

Under President Donald Trump, relations saw an immediate reset. Orbán “welcomed” Trump’s 2016 presidential victory8 and Trump equally welcomed Orbán, inviting him to the White House in May 2019 to “lavish praise” on the prime minister.23 Orbán’s Hungary and Trump’s America shared an embrace of nationalism, “authoritarian populist"24 governance, and skepticism of Western alliances, but they did have tense moments. For instance, the US considered Hungary a “growing liability” for the transatlantic alliance and reportedly considered sanctioning Orbán’s close associates in 2019.25

One significant “liability” is Hungary’s continued use of China’s Huawei 5G technology,26 despite US warnings that Huawei is a national security risk and should be shunned.5 Orbán’s government even allowed Huawei to establish an R&D center in Budapest in 2020.27

This tech-driven tension that originated during the Trump era remains a growing issue and one of the Biden administration’s primary challenges as it seeks to strengthen its leadership and improve its competitiveness in the CEE region.

CHALLENGES POSED TO THE TRANSATLANTIC ALLIANCE BY HUNGARY-CHINA RELATIONS

The Sino-Hungarian relationship has raised the transatlantic alarm and ultimately creates the following primary challenges:

- First, it emboldens Orbán and exacerbates ideological and policy divisions within the EU, making a united EU and joint US-EU response to China more difficult.

- Second, BRI and the relationship lays bare the US’s inability to establish a strong economic presence in the CEE region to compete with China. Additionally, the relationship, especially Hungary’s use of Huawei, puts into relief the US’s lack of technology leadership on infrastructure and telecommunications networks development in Europe.

Responding to these challenges requires strategies at the US and transatlantic levels. The West must be careful not to misjudge the nature and degree of the threat the Sino-Hungarian relationship poses or misunderstand what drives the relationship, lest it overreact politically and worsen the situation.

UNDERSTANDING HUNGARY-CHINA RELATIONS

To properly address the challenges posed by Hungary-China relations, the transatlantic alliance must understand several points. First, contrary to the perception created by the Hungarian and Chinese governments, the relationship offers limited economic benefits for Hungary, which therefore remains largely dependent upon the EU and the US. Second, Orbán himself is the main driving force behind Hungary’s pro-China policy; his personal cost-benefit analysis of working with China comes before Hungary’s more generally. Third and last, there is a minimal threat to the transatlantic alliance of a Chinese “Trojan horse” in Hungary controlling foreign policy.

THE PERCEPTION VERSUS REALITY OF HUNGARY'S GAINS

Seeking to ease its economic dependence on the West following the 2008 financial crisis, Hungary adopted an “Opening to the East Strategy” to cultivate ties with China; the 16+1 initiative and BRI were therefore welcome opportunities.

From the start of 16+1 and BRI, the Hungarian and Chinese governments have pointed to developments that suggest Hungary gains substantially from the relationship and that their ties are “prosperous,” in the words of Xinhua, a Chinese state-run news agency.28 For instance, the governments note that China is now Hungary’s greatest trade partner outside of the EU, with annual trade worth approximately $9 bn.29

Since 2013, Hungary has been one the largest recipients of the billions of dollars China has poured into infrastructure projects in CEE.30 It boasts the highest level of cumulative Chinese FDI from 2000 to 2020 of all the EU’s CEE countries, ($3.1 bn), 23% more than second-place Poland (see Figure 3).31 Hungary also reports that last year China invested almost $6 bn in the country (see Figure 4), more than most other CEE members.32

Hungary and China have also signed a deal to build the Belgrade-to-Budapest railway.33 Furthermore, the Chinese and Hungarian governments have frequently held talks at 16+1 summits and BRI forums, and established a “comprehensive strategic partnership,”34 setting the stage for further cooperation.

At first glance, these developments give the impression that Hungary has seen large gains and has strengthened its ties with China — and thereby has also decreased its dependence on the EU. The reality, however, is a different story.

Few, if any, experts find that Hungary has gained economically from its relations with China in a way that substantially threatens the EU. Most, in fact, find the opposite.35 Hungary’s post-2010 gains have been modest, exaggerated, or underwhelming at best, and completely lacking at worst.

First, the Opening to the East policy has failed to deliver, with Hungary increasing its trade dependence on China from 2009 to 2014 by less than 0.5%36 and keeping its trade dependence on the EU at over 75%. Second, Hungary’s $3.2 bn cumulative completed Chinese FDI is minimal compared with the rest of Europe; Germany and the UK have received more than 9 times that amount (see Figure 3), reflecting China’s priorities and preference for ties with Western Europe over Hungary.

Third, Hungary received only $4.07 bn in Chinese investment last year — not $5.95 bn or $5.36 bn, as the Hungarian and Chinese governments respectively claimed. Indeed, both governments inflated their figures to create the illusion that China was more invested and involved in Hungary than it actually was (see Figure 4).36 Fourth, the Belgrade-to-Budapest railway offers little, if any, economic benefit to Hungary; some estimates suggest it could take between 130 and 2,400 years (!) before Hungary makes a profit from it.37 Fifth, from 2010 to 2019, Hungary-China export and import levels decreased — not increased — by 16% and 14% respectively.38 The reality is clear: The cost-benefit analysis shows that Hungary, as opposed to Orbán himself, gains little from its relationship with China. Rationally speaking, abandoning the EU and the US in favor of China is not in Hungary’s economic or political interests.

ORBAN's 'ONE MAN SHOW'

If Hungary does not economically profit from its relationship with China, what drives the relationship and why does Hungary push to work with China? The answer: Orbán. As an authoritarian leader, one of Orbán’s main goals, especially approaching this year’s elections, is to maintain his support and legitimize his illiberal regime, sometimes even at a cost to his country. Following this logic, the prime minister cultivates a relationship with China for several key reasons:

- Orbán seeks to maintain a set of strong illiberal “friends,” such as Russia, Turkey, Brazil, and China, that legitimize his regime. In other words, in cultivating economic partnerships with countries like China, Orbán seeks to ensure that he has economic and political alternatives if he should sever Hungary’s relationship with the EU and the US.

- Once Orbán realized the Chinese government would ultimately not be Hungary’s economic savior, he began to leverage Beijing for political gain in his battles with Brussels. By threatening to turn toward China, Orbán seeks to create the impression that he has a strong hand. In politics, perception often trumps reality.

- Orbán’s inner circle directly gains from his relationship with China. For example, Opus Global, a company controlled by Orbán’s oligarch friend Lőrinc Mészáros, “won” the contract to build Hungary’s section of the Budapest-to-Belgrade railway. The $2.1 bn deal could earn Mészáros a princely sum.39

Ultimately, Hungary’s China policy is “not a national strategy, but a one-man show,” says Tamás Matura, an expert on central and eastern Europe’s relations with China.40 The relationship is a function of Orbán himself. The opposition parties and candidates do not share the prime minister’s regard for China, especially since the controversy around the creation of China’s Fudan University campus in Budapest showed that being anti-China can poll well. If Orbán were to lose to the United Opposition in Hungary’s 2022 parliamentary elections, the country would likely do an about-face on its China policy.40

THE TROJAN HORSE FALSE ALARM

Ever since Hungary-China relations intensified in the early 2010s, journalists and news organizations have peddled the idea that Hungary is China’s “Trojan horse” in Europe,41 implying that China has influence in and control over Hungary and thereby poses a threat to the EU. Some scholars argue that China invests in CEE countries such as Hungary to achieve political objectives such as a pro-China EU policy42 and that China strategically invests in countries that offer a potentially high political reward.43 If indeed true, Hungary would therefore become a threat to be addressed aggressively and rapidly by the West.

Admittedly, China possesses indirect influence over Hungarian foreign policy through the prime minister: The more Chinese investment benefits Orbán personally, more he will encourage the government to adopt pro-China stances and partnerships such as the Belgrade-to-Budapest railway. Indeed, even without Chinese pressure to engage, Orbán seeks to cultivate ties and reap his own benefits from Chinese investments in Hungary, whether or not his country does.

Ultimately, however, despite past claims and current impressions, Sino-Hungarian economic ties do not grant China any direct, measurable political influence in Hungary or over EU foreign policy decisions vis-à-vis China. In other words, there is little evidence that the Chinese government invests in Hungary with a view to gain political favors such as pro-China EU-level policy. One study, for instance, found no change in Hungary’s votes within the EU on imposing anti-dumping measures (ADMs) on Chinese goods before and after the 16+1 Cooperation began (in fact, it has supported more ADMs against China since 2011).44

There is also no evidence that China is directly influencing Hungary to block EU statements against it. Indeed, Hungary, or Orbán specifically, is very pro-China already and therefore China has no need to pressure Hungary directly.44 Interestingly, though China appreciates the pro-China gestures, Matura said his Chinese counterparts have told him that sometimes China would rather Hungary not block the statements, lest it appear that the Chinese government has more (malign) influence in the CEE region than it actually does.40 In short, China is less of a string-puller in Hungary than is sometimes portrayed.

POLICY OPTIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

EXISTING TOOLS AND PROPOSED SOLUTIONS

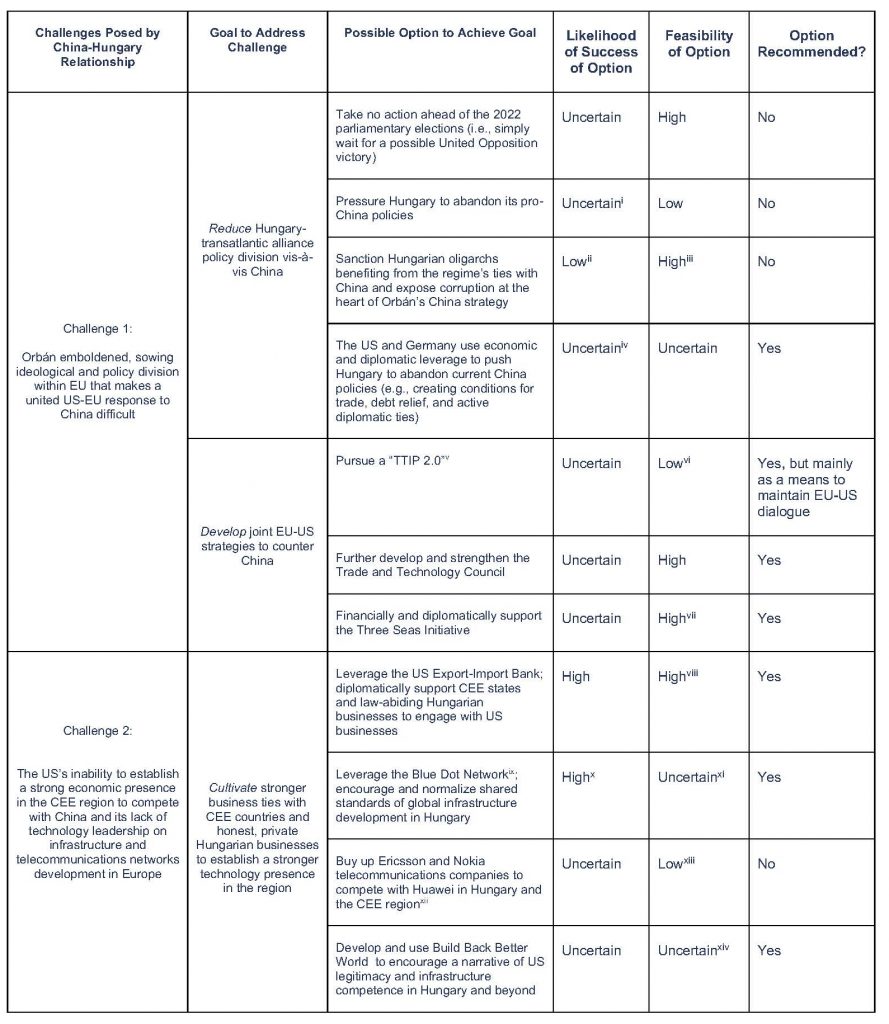

Faced with two major challenges and given the nature of the relationship, the transatlantic alliance has several options (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Responding to the China-Hungary Relationship: Challenges, Goals, and Options

[i] Tamás Matura (assistant professor, Corvinus University of Budapest), interview with Grzegorz Stec of EU-China Hub, June 2020, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5e374540bf646e003f3e4e4d/t/5ef7391efe8b687d4e50e293/1593260373849/EU_China_Hub_Interview_Tamas_Matura.pdf.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Both Matura (in interview with author) and Bermingham in “Germany ‘has all the tools’” suggest that German leverage can be effective. The potential success of US diplomatic leverage is uncertain.

[iv] François Venne, “Trading Places: Putting China in the Hot Seat,” Europe’s Edge for Center for European Policy Analysis, 3 August 2021, https://cepa.org/trading-places-putting-china-in-the-hot-seat/.

[v] Kimberly Amadeo, “Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP),” The Balance, 29 April 2021, https://www.thebalance.com/transatlantic-trade-and-investment-partnership-ttip-3305582, accessed October 21, 2021.

[vi] “Completing Europe: The Three Seas Initiative, featuring Congresswoman Marcy Kaptur,” Atlantic Council, 1 April 2021, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/commentary/event-recap/completing-europe-the-three-seas-initiative-featuring-congresswoman-marcy-kaptur/, accessed October 21, 2021.

[vii] Stephen Renna (former Chief Banking Officer, Export-Import Bank of the United States), interview with the author, 15 July 2021.

[viii] Mercy A. Kuo, “Blue Dot Network: The Belt and Road Alternative,” The Diplomat, 7 April 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2020/04/blue-dot-network-the-belt-and-road-alternative/, accessed October 21, 2021.

[ix] Kaush Arha, “Blue Dot Network: The Belt and Road Alternative,” Atlantic Council, 12 June 2021, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/a-hidden-key-to-the-g7s-infrastructure-ambitions-blue-dot-network/, accessed October 21, 2021.

[x] The Blue Dot Network is currently in discussion with the European Union according to https://thediplomat.com/2020/04/blue-dot-network-the-belt-and-road-alternative/. The projected outcome of these talks is still unclear.

[xi] Gordan Chang, The Great US-China Tech War (New York: Encounter Books, 2020).

[xii] David Shepardson, “White House dismisses idea of U.S. buying Nokia, Ericsson to challenge Huawei,” Reuters, 7 February 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-china-spying-huawei-tech-idUSKBN2012A5, accessed October 21, 2021.

[xiii] Mordechai Chaziza, “The “Build Back Better World”: An Alternative to China’s BRI for the Middle East?” MEI@75, 20 July 2021, https://www.mei.edu/publications/build-back-better-world-alternative-chinas-bri-middle-east, accessed October 21, 2021.

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

To address the first challenge, the transatlantic alliance should seek to reduce divisions between the West and Hungary on China policy. In considering ways to do this, it is important to weigh each option’s feasibility and the likelihood of success.

Given that Orbán’s political opponents would likely lead Hungary away from its pro-China policies, one option could be to take no action ahead of the 2022 parliamentary elections, avoid confrontation with Orbán, and hope for a United Opposition victory. As of December 15, Orbán's Fidesz and the United Opposition are polling at 48% and 46%, respectively.45 With victory far from certain, it would be imprudent to take no action and leave Orbán’s pro-China and resulting anti-West policies unaddressed, lest it legitimize Orbán’s regime and normalize EU disunity.

Another option would be for the EU to threaten to cut its funding to Hungary unless the country severs its ties with China. The EU has made that threat before but has not followed through, and unless it finds some new resolve, it is not likely to do so this time, even as some experts predict the gambit would work.46 Other scholars warn it could backfire: Orbán thrives on conflict with the EU47 and such a threat could help him shore up support and mobilize his base against the so-called “Brussels elites.”48 This option is neither feasible nor certain to succeed, and it is therefore not recommended.

Pushing Orbán to abandon corruption-ridden deals with China such as the Belgrade-to-Budapest railway would be difficult, but it would be feasible to sanction Orbán’s oligarch friends, such as Mészáros, who have a piece of the project. Not only is there a precedent for US sanctions against those involved in corruption (such as the sanctions against former Slovak general prosecutor Dobroslav Trnka),49 in 2019 the Trump administration allegedly made plans to sanction Mészáros.50 But given the pervasiveness of corruption in Hungary, highlighting graft by punishing Orbán’s inner circle is unlikely to shift public opinion, let alone push the prime minister to abandon the deal and his pro-China stance.47

Ultimately, the best way to bridge the gap between Hungary and the transatlantic alliance on China policy is to:

- Pressure Orbán at the highest levels of the US and German governments to align Hungary with Western foreign policy on China. Given that Hungary values US recognition and diplomatic contact and depends heavily upon German trade, the US and Germany hold great leverage over Hungary. They could make trade, debt relief, or active diplomatic ties conditional upon a change in Hungary’s policy, starting with a focus on Huawei tech and the Belgrade-to-Budapest railway. It’s uncertain, though, if there’s the political will to apply such pressure. For instance, Germany’s willingness to adopt such a policy will depend on the politics of the new coalition and the newly selected German prime minister, Olaf Scholz.51

Even if Orbán’s Hungary does not change policies, the transatlantic alliance should continue to develop joint US-EU policies to counter China. As an EU member, Hungary will by default be involved and pushed to engage in transatlantic strategies for competing — not partnering — with China. These strategies involve:

- Engaging in continuous dialogue on a potential TTIP 2.0 plan and further discussing the Trade and Technology Council (TTC) to encourage a united Western strategy to face China. Though TTIP failed before launch in 2017, international trade is currently not popular in the US, and the TTC is still in its early stages, both could make an impact. The implementation of TTIP 2.0 in particular would be difficult. But even if TTIP negotiations ultimately fail, a new discussion on expanding free trade and how it can help to counter China and benefit the West would be opened.52

- The US supporting the Three Seas Initiative (3SI) by passing the Transatlantic Telecommunications Security Act and fulfilling its pledge of $1 bn for the Three Seas Initiative Investment Fund. Continued public, diplomatic support for the 3SI would also help the US Development Finance Corp. to better compete with Huawei 5G. Enjoying bipartisan support in the US, the 3SI is a feasible option,53 and with Hungary itself a member of the 3SI, its potential impact on Hungary and for competition with China is great.

To address the second challenge, the US should cultivate stronger business ties with law-abiding private businesses in Hungary (and in CEE countries more generally) to establish a stronger technology presence and challenge Huawei and Chinese infrastructure projects in Hungary.

Some experts54 and now former Attorney General William Barr have suggested buying up or investing in Ericsson and Nokia telecommunications networks to compete with Huawei.55 This ambitious idea, however, was quickly shot down56 by the White House, and future administrations are unlikely to pursue it.

Fortunately, the transatlantic alliance has several promising strategies:

- Use some of the $27 bn earmarked for the US Export-Import Bank’s Program on China and Transformational Exports57 to focus on telecommunications and infrastructure in Hungary. The US government should also diplomatically support law-abiding private Hungarian businesses seeking to engage with US businesses.57 Doing so will increase US competitiveness while not legitimizing the Orbán regime’s actions.

- Push the EU to join the Blue Dot Network to expand its reach into the CEE region and Hungary. Through this network, the EU can normalize and push for higher standards of global infrastructure development in Hungary and the region to increase the US presence and challenge Chinese practices.58 Though the US is unlikely to offer infrastructure prices lower than China to Hungary and is therefore unlikely to change Orbán’s mind, it can compete on standards and quality, possibly helping to expand US business in other CEE countries and the private sector in Hungary.57

Pursue the Biden administration’s Build Back Better World initiative to encourage a narrative of US legitimacy and infrastructure competence in Hungary and beyond. This strategy is feasible and promising, for it can be easily kick-started by passing the widely supported Strategic Competition Act of 2021, which recognizes the importance of US leadership and the need to invest in its ability to outcompete China.59 This policy may take time to have an effect but will ensure continued transatlantic dialogue and US involvement in the region.

CONCLUSION

As the transatlantic alliance seeks to respond effectively to the growing threat from China, the Sino-Hungarian relationship has become a thorn in its side. Fortunately for the West, the notion that China controls Hungary or has created a Hungarian “Trojan horse” through economic ties is unfounded and exaggerated. With Orbán — not China — in control of Hungary’s China policy and the cause of its ideological and policy divergence with the West, the US is left with several options as it seeks to unite the transatlantic alliance and confront China. From seeking to pressure Orbán to align with the West, to moving forward with joint EU-US China policies and adopting strategies to increase US ties with the CEE region, China will not have the last word in Europe.

- John Chalmers and Robin Emmott, “Hungary blocks EU statement criticizing China over Hong Kong, diplomats say,” Reuters, April 16, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/hungary-blocks-eu-statement-criticising-china-over-hong-kong-diplomats-say-2021-04-16/, accessed 30 July 2021. [↩]

- Hans von der Burchard and Jacopo Barigazzi, “Germany slams Hungary for blocking EU criticism of China on Hong Kong,” Politico, March 10, 2021, https://www.politico.eu/article/german-foreign-minister-slams-hungary-for-blocking-hong-kong-conclusions/, accessed 30 July 2021. [↩] [↩]

- Dr. Matura Interview Tamás Matura (assistant professor, Corvinus University of Budapest), interview with the author, 14 July 2021. [↩]

- Szabolcs Panyi, “Hungary Could Turn Into China’s Trojan Horse in Europe,” Balkan Insight, April 9, 2021, https://balkaninsight.com/2021/04/09/hungary-could-turn-into-chinas-trojan-horse-in-europe//, accessed 30 July 2021. [↩]

- Susan Decker, “Huawei Bets Bigs on European 5G Patents Despite Trump’s Pressure,” Politico, March 12, 2021, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-12/huawei-bets-big-on-european-5g-patents-despite-trump-s-pressure, accessed 30 July 2021. [↩] [↩]

- Daniel McLaughlin, “Hungary’s Leader Urges Europe to Reject Liberal Values and Immigration,” Irish Times, March 15, 2019, https://www.irishtimes.com/news/world/europe/hungary-s-leader-urges-europe-to-reject-liberal-values-and-immigration-1.3827401, accessed 30 July 2021. [↩] [↩]

- James Kirchick, “Is Hungary Becoming a Rogue State in the Center of Europe?,” Brookings, January 7, 2019, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2019/01/07/is-hungary-becoming-a-rogue-state-in-the-center-of-europe/, accessed 18 October 2021. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Martin Fletcher, “Is Hungary the EU’s First Rogue State? Viktor Orban and the Long March from Freedom,” NewStatesman, April 1, 2017, https://www.newstatesman.com/world/europe/2017/08/hungary-eus-first-rogue-state-viktor-orban-and-long-march-freedom, accessed 18 October 2021. [↩] [↩]

- Gabriella Gricius, “Hungary’s Relationship with Russia Poses a Risk for Europe.” Global Security Review. June 10, 2019. https://globalsecurityreview.com/hungarys-growing-relationship-russia/, accessed 30 July 2021. [↩]

- “Hungary’s Viktor Orban Accuses EU of ‘Abuse of Power.’ ” DW/Deutsche Welle. September 11, 2018. https://www.dw.com/en/hungarys-viktor-orban-accuses-eu-of-abuse-of-power/a-45442385, accessed 30 July 2021. [↩]

- “How Viktor Orban Hollowed out Hungary’s Democracy,” The Economist, August 29, 2019, https://www.economist.com/briefing/2019/08/29/how-viktor-orban-hollowed-out-hungarys-democracy, accessed 30 July 2021. [↩]

- Daniel McLaughlin, “Hungary’s Leader Urges Europe to Reject Liberal Values and Immigration,” Irish Times March 15, 2019, https://www.irishtimes.com/news/world/europe/hungary-s-leader-urges-europe-to-reject-liberal-values-and-immigration-1.3827401, accessed 18 October 2021. [↩]

- Andrew Roth, “Belarus protests: Who are the Key Players and What Do They Want?” The Guardian, August 18, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/aug/18/belarus-protests-who-are-the-key-players-and-what-do-they-want, accessed 30 July 2021. [↩]

- Sandor Zsiros and Joanna Gill, “Hungary and Poland block EU's COVID-19 recovery package over new rule of law drive.” Euronews, November 18, 2020, https://www.euronews.com/2020/11/16/hungary-and-poland-threaten-coronavirus-recovery-package, accessed 18 October 2021. [↩]

- Chalmers Emmott, “Hungary blocks EU statement.” [↩]

- “Hungary,” European Union, September 13, 2019, https://europa.eu/european-union/about-eu/countries/member-countries/hungary_en, accessed 30 July 2021. [↩] [↩]

- Leonid Bershidsky, “How the EU Plans to Punish Hungary and Poland,” Bloomberg, January 18, 2019, https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2019-01-18/how-the-eu-plans-to-punish-hungary-and-poland, accessed 30 July 2021. [↩]

- “Hungarian Foreign Trade in Figures,” Santander Trade Markets, July 2021, https://santandertrade.com/en/portal/analyse-markets/hungary/foreign-trade-in-figures, accessed 30 July 2021. [↩] [↩]

- Edit Inotai and Claudia Ciobanu, “Can Hungary and Germany Kiss and Make Up,” Balkan Insight, December 9, 2020, https://balkaninsight.com/2020/12/09/can-hungary-and-germany-kiss-and-make-up/, accessed 30 July 2021. [↩]

- Finbarr Bermingham, “Germany ‘has all the tools’ to whip Hungary into line on Hong Kong, but does it really want to?,” South China Morning Post, 12 May 2021, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3133097/germany-has-all-tools-whip-hungary-line-hong-kong-does-it, accessed 30 July 2021. [↩]

- Patrick Kingsley, “Hungary’s Leader Was Shunned by Obama, but Has a Friend in Trump,” New York Times, 15 August, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/15/world/europe/hungary-us-orban-trump.html, accessed 30 July 2021. [↩]

- “Orbán blames poor relations with Obama administration on ideological differences.” Budapest Beacon, 25 November 2016, https://budapestbeacon.com/orban-blames-poor-relations-with-obama-administration-on-ideological-differences/, accessed 30 July, 2021. [↩]

- Peter Baker, “Viktor Orban, Hungary’s Far-Right Leader, Gets Warm Welcome From Trump,” New York Times, 13 May, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/13/us/politics/trump-viktor-orban-oval-office.html, accessed 30 July 2021. [↩]

- Ronald Inglehart and Pippa Norris, Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit and the Rise of Authoritarian Populism (New York, NY USA: Cambridge University Press, 2019). [↩]

- Ian Talley, “US Keeps Sanctions at the Ready Even as Trump Courts Hungarian Leader,” Wall Street Journal, 14 May 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-keeps-sanctions-at-the-ready-even-as-trump-courts-hungarian-leader-11557867566, accessed 30 July 2021. [↩]

- Pablo Gorondi, “Hungary says Huawei to help build its 5G wireless network,” ABC News, 19 November 2020, https://abcnews.go.com/Business/wireStory/hungary-huawei-build-5g-wireless-network-66758617, accessed 30 July 2021. [↩]

- “Huawei establishes a new R&D center in Budapest,” Hungarian Insider, 22 October 2020, https://hungarianinsider.com/huawei-establishes-a-new-rd-center-in-budapest-5618/, accessed 30 July 2021. [↩]

- “Backgrounder: Economic ties between China and Hungary prosperous,” Xinhua, 22 May 2019, accessed 8 September 2021. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2019-05/22/c_138078049.htm. [↩]

- “Orbán Praises Chinese Companies in Hungary, China’s Silk Road Plan,” Hungary Today, 24 May 2019, https://hungarytoday.hu/orban-chinese-companies-hungary-china-silk-road/, accessed 30 July 2021. [↩]

- Dusan Stojanovic,“Orbán Praises Chinese Companies in Hungary, China’s Silk Road Plan,” AP News, 10 April 2019, https://apnews.com/article/eastern-europe-ap-top-news-international-news-croatia-china-d121bfc580f04e73b886cc8c5a155f7e/, accessed 30 July 2021. [↩]

- Agatha Kratz et al., Chinese FDI in Europe 2020 Update, Central and Eastern European Center for Asian Studies, June 2021, available at: https://rhg.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/MERICSRhodium-GroupCOFDIUpdate2021.pdf. [↩]

- Tamas Matura and CEECAS Team, Chinese Investment in Central and Eastern Europe – A reality check, Central and Eastern European Center for Asian Studies, April 2021, available at: https://www.china-cee-investment.org/. [↩]

- Krisztina Than and Anita Komuves, “Hungary, China sign loan deal for Budapest-Belgrade Chinese rail project,” Reuters, April 24, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-hungary-china-railway-loan-idUSKCN226123/, accessed 30 July 2021. [↩]

- Tamas Matura, “ Absent political values in a pragmatic Hungarian China policy,” in Political values inEurope-China relations, European Think-tank Network onChina (ETNC), December 2018, available at: https://www.academia.edu/38210801/Absent_political_values_in_a_pragmatic_Hungarian_China_policy [↩]

- Pawel Paszak of the Instytut Nowej Europy, for instance, claims that the ‘Opening to the East’ policy “hasn’t delivered” for Hungary. [↩]

- Tamas Matura, “Hungary and China Relations” in China’s Relations with Central and Eastern Europe, ed. Weiqing Song, 1st ed., (New York: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group, 2018), 147. [↩] [↩]

- Zoltán Vörös, “Who Benefits From the Chinese-Built Hungary-Serbia Railway?” The Diplomat, January 4, 2018, https://thediplomat.com/2018/01/who-benefits-from-the-chinese-built-hungary-serbia-railway/, accessed 30 July 2021. [↩]

- “Hungary trade balance, exports and imports by country and region 2010,” World Integrated Trade Solution, 2021, https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/HUN/Year/2010/TradeFlow/EXPIMP, accessed 30 July 2021. [↩]

- “Chinese money flows to friend of Hungarian PM Orban in contract for Budapest-Belgrade railway,” Alliance for Securing Democracy, 2021, https://securingdemocracy.gmfus.org/incident/chinese-money-flows-to-friend-of-hungarian-pm-orban-in-contract-for-budapest-belgrade-railway/, accessed 30 July 2021. [↩]

- Matura, interview with the author, 14 July 2021. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Examples range from more reputable and known sources such as the Balkan Insight and France24, to more obscure news agencies such as India.com and News Beezer. Even this brief’s own author once used the Trojan Horse terminology to describe China in Hungary. [↩]

- Liu, Z. (2014) “The Analysis of China’s Investment in V4”, in Current Trends and Perspective on Development of China-V4 Trade and Investment, Bratislava, March 12-14, 2014 (Bratislava, University of Economics in Bratislava, Faculty of International Relations). As cited in Matura, “Hungary and China Relations,” 150. [↩]

- Brown, K. and Wood, P. (2009) “China ODI: Buying into the Global Economy”, XRG C-ODI Report, October 2009. As cited in Matura, “Hungary and China Relations,” 150. [↩]

- Matura, “Hungary and China Relations,” 150. [↩] [↩]

- “Hungary — National parliament voting intention,” Politico, 6 October 2021, https://www.politico.eu/europe-poll-of-polls/hungary/, accessed October 21, 2021. [↩]

- Zoltán Ádám (assistant professor, Corvinus University of Budapest), interview with the author, 26 July 2021. [↩]

- Matura, interview with Grzegorz Stec of EU-China Hub. [↩] [↩]

- Cordelia Buchanan Ponczek, “What Can We do About Hungary and China,” Center for European Policy Analysis, 4 February 2021, https://cepa.org/what-can-we-do-about-poland-and-hungary/. [↩]

- Daniel Hegedus, “Why the US should meddle in Europe to stop autocratizing NATO allies,” The Hill, 21 May 2021, https://thehill.com/opinion/national-security/552402-why-the-us-should-meddle-in-europe-to-stop-autocratizing-nato, accessed October 21, 2021. [↩]

- Ian Talley, Drew Hinshaw and Anita Komuves, “U.S. Keeps Sanctions at the Ready Even as Trump Courts Hungarian Leader,” The Wall Street Journal, 14 May 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-keeps-sanctions-at-the-ready-even-as-trump-courts-hungarian-leader-11557867566, accessed October 21, 2021. [↩]

- Inotai and Ciobanu, “Can Hungary and Germany Kiss and Make Up.” ; Edit Inotai and Claudia Ciobanu, “Can Hungary and Germany Kiss and Make Up,” Balkan Insight, December 9, 2020, https://balkaninsight.com/2020/12/09/can-hungary-and-germany-kiss-and-make-up/, accessed 30 July 2021. [↩]

- François Venne, “Trading Places: Putting China in the Hot Seat,” Europe’s Edge for Center for European Policy Analysis, 3 August 2021. https://cepa.org/trading-places-putting-china-in-the-hot-seat/. [↩]

- Anthony B. Kim, “U.S. Support for 3 Seas Initiative Is Smart, Strategic,” The Heritage Foundation, 8 July 2021, https://www.heritage.org/global-politics/commentary/us-support-3-seas-initiative-smart-strategic, accessed October 21, 2021. [↩]

- Gordon Chang, The Great US-China Tech War (New York: Encounter Books, 2020). [↩]

- Oliver O’Connell, “5G: Trump administration suggests US and allies invest in Nokia and Ericsson, despite UK opening door to Huawei,” Independent, 6 February 2020, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/us-politics/5g-trump-william-barr-nokia-ericsson-huawei-uk-china-a9322686.html, accessed October 21, 2021. [↩]

- Shepardson, “U.S. buying Nokia.” [↩]

- Stephen Renna (former chief banking officer, Export-Import Bank of the United States), interview with the author, 15 July 2021. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- “Blue Dot Network,” US Department of State, 2021, https://www.state.gov/blue-dot-network/, accessed 8 September 2021. [↩]

- “Chairman Menendez Announces Bipartisan Comprehensive China Legislation,” United States Committee on Foreign Relations, 8 April 2021, https://www.foreign.senate.gov/press/chair/release/chairman-menendez-announces-bipartisan-comprehensive-china-legislation#:~:text=The%20Strategic%20Competition%20Act%20of%202021%20is%20a%20recognition%20that,diplomacy%20in%20our%20core%20values.&text=The%20scope%2C%20scale%20and%20urgency,China%20challenge%20demands%20nothing%20less.%E2%80%9D, accessed 30 July 2021. [↩]