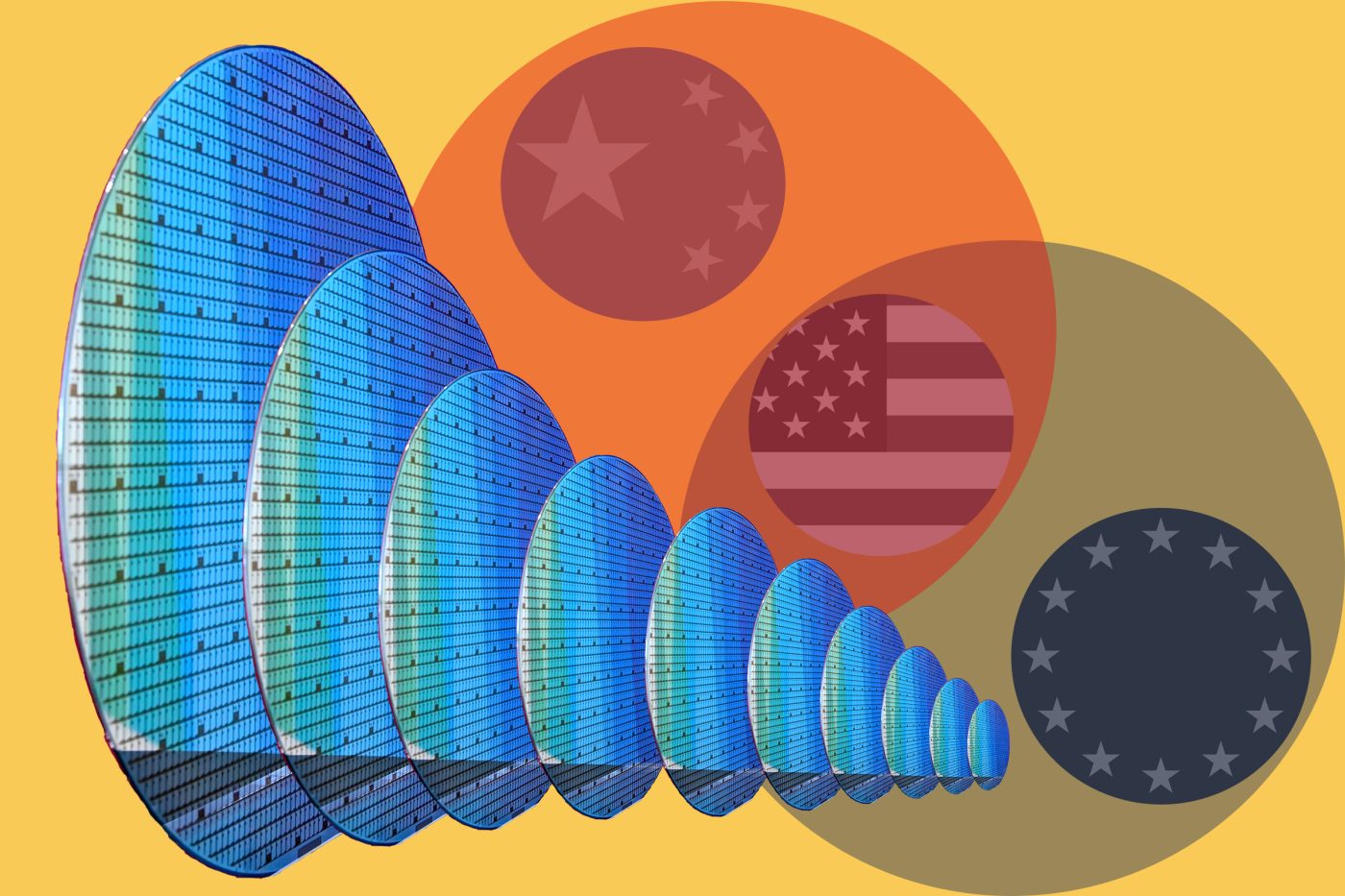

In the Framework on an Agreement on Reciprocal, Fair, and Balanced Trade, a section centers on two key issues: a European pledge to buy US AI chips and a commitment to align on security safeguards.

At first glance, this looks like a breakthrough: a transatlantic alignment on AI chips, the foundational technology for models, systems, and agents. It projects the image of cooperation in a landscape otherwise marked by friction. But a closer look reveals that both the purchase numbers and the security commitments are provisional, leaving open key questions about scale, timing, and certainty.

Viewed this way, the framework reflects a broad pattern in US trade and technology diplomacy: headline figures first, implementation later.

For Europe, it falls short in two ways: it fails to establish a binding mechanism to fund or allocate $40 billion in chip purchases, and it fails to guarantee supply. For the US, it offers the optics of a significant commitment with limited substance. A final agreement is intended and may settle some of these issues (though the timing and substance of a final deal may be complicated by President Donald Trump’s threat of export restrictions on US AI chips to Europe).

Until then, the practical effect is best described as net neutral, with a real risk of turning negative if new conditions slow European chip purchases.

The AI Chips Purchase

The EU’s pledge to purchase $40 billion of US AI chips is a classic memorandum of understanding language. It’s aspirational, rather than binding, and doesn’t specify who will buy, how many chips, or when.

Two potential EU purchase streams exist.

First, there are AI Factories. The factories aim to pool AI-optimized supercomputers, data, and expertise so that European startups, researchers, and public bodies can build AI models and systems. The existing EuroHPC Joint Undertaking for supercomputer procurement contains an envelope of $464 million in 2024 and up to $929 million through 2027. In addition, the European Commission has stated that the EU plus its member states are “mobilizing” (that is, aiming to pool together) north of $2 billion for the new AI Factories.

Second, there are AI Gigafactories, which are massive (100,000 AI chips each) compute facilities designed to handle the development and operation of extensive AI systems. Separate from the AI Factories, the European Commission targets an investment of more than $23 billion to deploy up to five sites, but no awards have been made to date.

Taken together, these lines total about $26 billion — and much of that is for facilities and operations rather than chips — so the framework’s “at least $40 billion” chip pledge is not financed.

In contrast to the framework’s energy provision, which runs through 2028, the chip language sets no purchase timeline. Absent clarification, it reads as a multi-year, staged commitment that could extend well past 2028.

To reach $40 billion on a 2028 horizon, the EU would have to do one of three things: (1) extend the purchase window well beyond 2028 (deferring outlays and diluting the near-term commitment); (2) materially expand EU-level budgets for US AI chips (politically and fiscally difficult); or (3) count member-state purchases outside EuroHPC toward the total. Extending the timeline would be the easiest path, though it would dilute the near-term impact of the pledge. The other two steps are politically and fiscally difficult.

Security Commitments

Beyond the headline numbers is the framework’s two-part security clause. The EU promises to align its safeguards with US requirements, while Washington promises only to “endeavor to facilitate” exports once those safeguards are in place.

These commitments are not automatic and do not ensure uniform access across 27 member states. Even after the EU adopts safeguards, the United States commits only to trying to facilitate exports. Washington is not guaranteeing supply (that depends on NVIDIA and others) and may not guarantee approval.

If the current language is retained, the US would preserve discretion, implying operator- and site-specific security approvals, perhaps coupled with periodic inspections, reporting obligations, and requirements to keep AI chips at authorized facilities. In effect, this would mirror the logic of the Data Center Validated End-User program, which ties export approvals to designated facilities and requires ongoing compliance monitoring.

Seen this way, the security provisions suggest that the Trump administration is reviving the tiering logic of the Biden administration’s rescinded AI Diffusion Rule. While the Rule explicitly placed EU countries in Tier 2, restricting their access to leading chips, the new deal’s security rules could reintroduce a de facto tiering system under another name, with chip export access conditional on site-specific trust designations and data center VEU-style oversight. What looks like Tier 1 unity in headlines may still function like Tier 2 treatment in practice.

Conclusion

The US-EU framework exemplifies a recurring challenge in modern trade diplomacy: the tension between political symbolism and operational substance. While the $40 billion commitment generates positive headlines about US-EU cooperation, the underlying financial and regulatory architecture suggests a constrained reality.

As implementation details emerge, the test will be whether both sides can translate the US-EU framework into binding commitments. If not, the framework will join a long list of initial deals that fall short of fiscal and operational reality.

Pablo Chavez is an Adjunct Senior Fellow with the Center for a New American Security’s Technology and National Security Program and a technology policy expert. He has held public policy leadership positions at Google, LinkedIn, and Microsoft and has served as a senior staffer in the US Senate.

Bandwidth is CEPA’s online journal dedicated to advancing transatlantic cooperation on tech policy. All opinions expressed on Bandwidth are those of the author alone and may not represent those of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis. CEPA maintains a strict intellectual independence policy across all its projects and publications.

2025 CEPA Forum Tech & Security Conference

Explore the latest from the conference.