Throughout Asia, cloud computing – distributed, off-site computing infrastructure in place of dedicated on-site “metal” – powers economic growth. Yet fears about the cloud’s impact on privacy, economic development, and national security are leading to policies such as data localization and other restrictions that hinder adoption. And the specter of a China-US trade war brings further uncertainty.

For every 1% of cloud adoption, the Asian Development Bank estimates a 0.07% increase in GDP among 11 high and middle-income countries in the Asia-Pacific region, ranging from Australia to Vietnam, and not including China. For Asian high adopters such as Singapore and New Zealand, the economic boost is estimated at more than 2% of GDP as digital trade booms, and cross-border cloud computing is set to boom.

Despite this potential bonanza, cloud policies in Asia must overcome complex regulatory hurdles that present major obstacles to adoption.

Start with privacy. While countries like Australia, Singapore, and Japan passed laws long ago and built well-seasoned enforcement agencies, other major countries such as Indonesia, Vietnam, India, and Thailand are only now implementing privacy rules.

The new laws are often problematic and create a patchwork of rules that are costly and difficult for firms to implement. These rules can include extraterritorial provisions, onerous breach notifications, and the requirement to appoint local registered agents or data privacy officers. They may have murky enforcement provisions that must be baked into cloud service offerings, increasing the cost of doing business in the cloud.

Countries with newly adopted privacy rules may have an opportunity to leapfrog regulations and adopt regulations to facilitate the adoption of cloud computing by increasing the interoperability of privacy rules with other jurisdictions. Take Indonesia’s 2022 Personal Data Protection Act, for example. Observers have noted that low public awareness and a lack of a dedicated, independent data protection authority will hamper rights protection and economic activity, as 21% of respondents to a government survey said they would not utilize digital platforms due to data privacy concerns. Looking to the EU’s experience, Japan, South Korea, or Singapore can smooth out these growing pains.

Another stumbling block is data sovereignty. While multilateral agreements seek to prohibit data localization, such as the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement between Singapore, New Zealand, Chile, and South Korea, some countries double down – seeing localization as a national security issue, and, more importantly, an opportunity for economic development.

For example, the 2019 Indonesian government’s Law No. 71 of 2019 requires data to be kept inside the country. The reasoning is clear: Indonesia’s Minister for Communication and Informatics says the localization requirements will strengthen the country’s technological and economic independence.

Under Vietnam’s 2022 Decree No. 53/2022/ND-CP, international companies having business activity in the country must store certain data locally and establish a branch or representative office in the country. Vietnam’s motivation is different than Indonesia’s; Vietnam seeks to reinforce government control and national security, and according to numerous analysts, this decree clarifies the 2018 National Cybersecurity Law.

Although the privacy, cybersecurity, and data localization rules stymie cross-border cloud adoption, a growing number of digital economy agreements are laying the groundwork for tech-enabled trade, including cloud services. Japan introduced a Data Free Flow with Trust initiative at the Osaka G20 in 2019. It has become a key pillar of the region’s approach to cross-border data governance, emphasizing interoperable privacy rules and standardized practices for the transfer, storage, and processing of data among private enterprises.

As discussed above, the DEPA trade deal includes provisions against data localization, with only a few exceptions. Similar provisions can also be found in agreements such as the CPTPP. The other leading regional trade deal, RCEP, also bans data localization, but has broader exceptions, and is more lenient to developing countries in adopting these more liberal cross-border obligations.

Another noteworthy development is ASEAN’s Digital Economy Framework Agreement, which contains data transfer, privacy, cybersecurity, and competition provisions. Currently under negotiation, the agreement may provide a valuable means for greater harmonization and interoperability of rules and greater cooperation between enforcement agencies regulating digital trade.

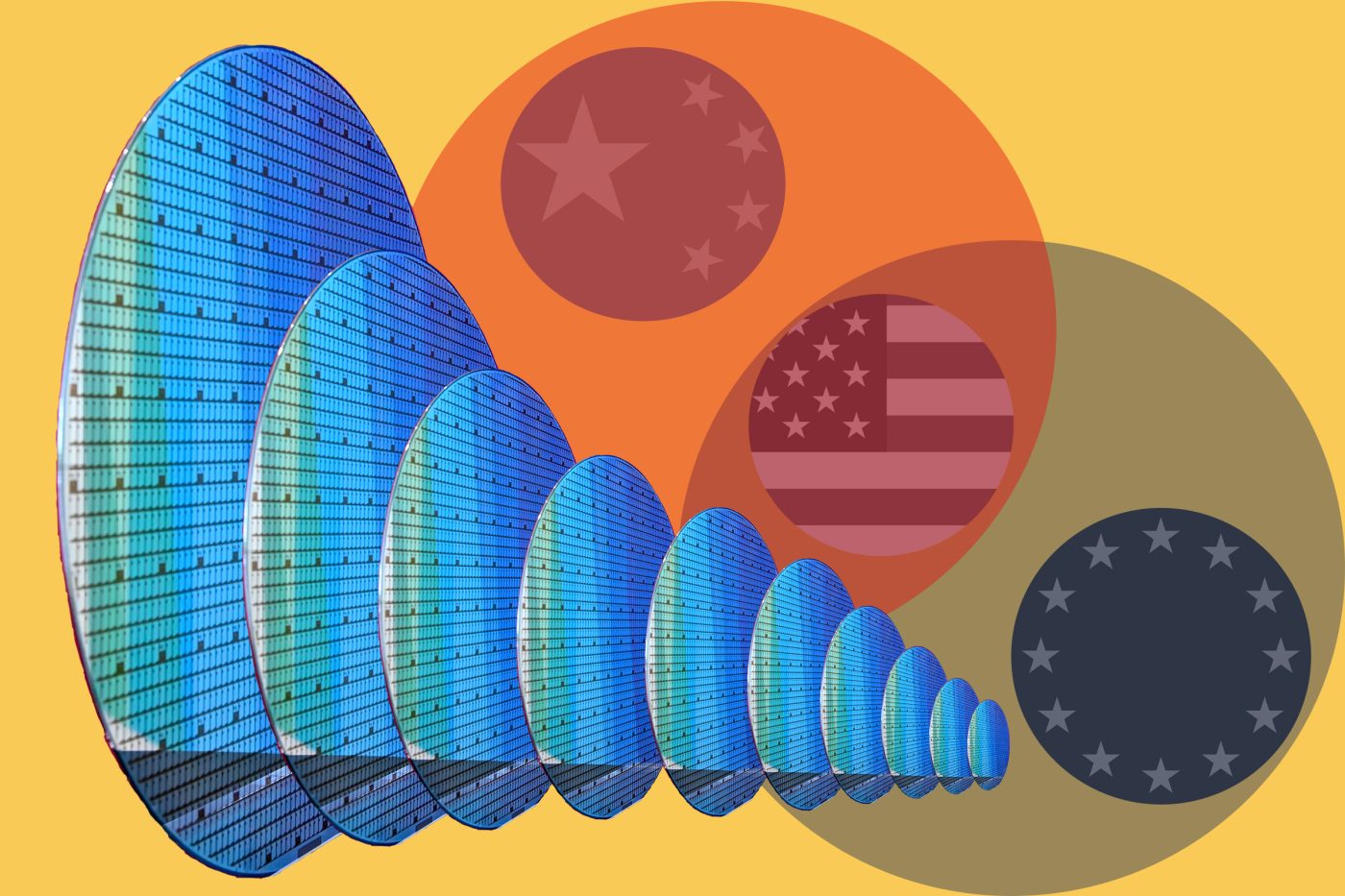

The sharpening competition between the US and China overshadows all these initiatives. Tensions over cloud computing echo previous debates about 5G telecommunications technology. The US and its allies, such as Japan, championed keeping out Chinese tech in favor of Western suppliers – often European firms such as Ericsson and Nokia – on the basis of national security grounds. Similar arguments are now used to support American cloud firms led by Google, Microsoft, and Amazon over China’s Alibaba.

In the case of 5G, the US and Japan expelled China-based market players from the field and leveraged export promotion and financing in third countries. Japan pledged support for the Philippines to build 5G network infrastructure without using Chinese brands Huawei or ZTE, although the country ultimately used Huawei technology despite these incentives. Vietnam avoided Chinese technology by rolling out its 5G network using European and domestic technology.

But China tech represents a fierce, low-cost competitor, and some key Southeast Asia countries look set to find a different balance between the superpowers. “It is quite unrealistic to expect 100% security from any telecoms system you buy,” former Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong of Singapore said about 5G. This sentiment among leaders in the region is likely to persist regarding any cybersecurity issues in cloud computing or emerging technology.

When geopolitical tensions between U.S. and Chinese cloud providers enter the equation, national security will remain a strategic backstop. Some countries, such as Vietnam, will adopt restrictive anti-Chinese measures. For the vast majority of countries in the region, though, economic development and business opportunity will continue to keep the door open.

As AI-enabled technologies drive the importance of cloud computing further in Asia, countries will assess their current economic needs and trade relationships against forecasts for a future where the US and China tech competition may drive digital ecosystems further apart. Governments in Asia will need to find a balance between sovereignty and security to release the benefits of cloud-generated economic growth.

Seth Hays is Managing Director at APAC GATES, a Taiwan-based management and digital rights consultancy. He also serves on the NGO Digital Governance Asia board and edits the Asia AI Policy Monitor newsletter.

Bandwidth is CEPA’s online journal dedicated to advancing transatlantic cooperation on tech policy. All opinions expressed on Bandwidth are those of the author alone and may not represent those of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis. CEPA maintains a strict intellectual independence policy across all its projects and publications.

2025 CEPA Forum Tech & Security Conference

Explore the latest from the conference.