Since Russia began its invasion of Ukraine a month ago, grassroots initiatives across Europe – especially in Lithuania and Norway – have been attempting to reach ordinary Russians by phone or text or other means to communicate about the war, cold-contacting people across the country, one at a time.

Has it had any effect? Some, it seems.

The Vilnius-based Paulius Senuta, is part of an initiative known as “Call Russia”. Recruiting Russian speakers – initially in Lithuania, but now from around the world — it has now made over 100,000 calls to Russia. To begin with, they hit a wall of opposition.

“Initially, the people who we were talking to — if they were not angry and shouting at us — they would basically (when they understood what the call was about) shut up and wouldn’t talk at all,” Senuta told this author. The organization decided to hire a psychologist to help them work out how to better communicate with those holding fundamentally different views.

Now, “we try not to speak ideologically, but to speak in humanitarian terms . . . inform them about the tragedy in Ukraine, which we believe every human being will sympathize with,” Senuta said.

The result, he says, is that people are starting to stay on the calls for longer — perhaps as what they hear in everyday life diverges more dramatically from state propaganda. And perhaps because carefully worded persuasion also has an effect.

“Once you sow that doubt in their head — you must be persuasive obviously to set that doubt — so you have to try hard. But once you set that doubt, the mechanism starts working on someone.” Senuta adds that they see better responses when callers speak Russian without an accent — and some calls run on for as long as an hour. “I think it’s wonderful, because you’re really having a proper conversation,” Senuta said.

Lithuania has something of a history with imaginative citizen-political projects. Following the 2014 Ukraine revolution, Russia’s annexation of Crimea, and its continuing war in the east of the country, a group of Lithuanians took it upon themselves to form the “Elves”, an online resistance movement that has now become a volunteer army of around 4,000. They flock to social media posting memes, countering disinformation, and monitoring “toxic” pages on Facebook, as one member recently told FRANCE 24.

Another Lithuanian influencer has been using Tinder, Bumble, and Badoo to spread the news about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, bypassing borders to reach people in Russia, and spearheading a campaign spurring other Lithuanians to do the same.

Agnė Kulitaitė uses a fake Badoo presence, “Natasha Romanova, 28” after the Marvel comics superhero, and her real name on Tinder, changing her location from Vilnius to Moscow in order to spread information about both the invasion of Ukraine and the whereabouts of Russian protests. The apps help her to communicate with people in an increasingly closed-off country, she says.

“I was inspired by a recent campaign that became popular around the world — encouraging people to go to Google reviews, travel to cafes, bars, restaurants in Russia, and leave feedback about the current situation in Ukraine,” she said.

Her tens of thousands of followers caught on quickly and spread it further, reaching several notable people including this year’s Lithuanian Eurovision representative, Monika Liu.

She advises her 42,000 Facebook followers to buy the Tinder Gold feature, which permits users to change location to anywhere in the world. Users then switch their location from Vilnius to cities in either Russia or Belarus, affix the Ukrainian flag on the profile photo, and explain – preferably in Russian – what is happening in their profile description. The posts are “about how people must open their eyes and see that the war was started by Vladimir Putin, and that he is now destroying innocent civilians in Ukraine, separating families and killing children,” she says. Selecting the widest possible range of people — men and women, from 18 to 100 years old — she reaching the highest possible radius from a set location. “Then swipe like there is no tomorrow.”

Her followers have obliged, creating profile descriptions saying things like: “Do something. Innocent civilians and children are dying. You must resist your despot! Protest! Take to the streets! They can’t jail everyone!”

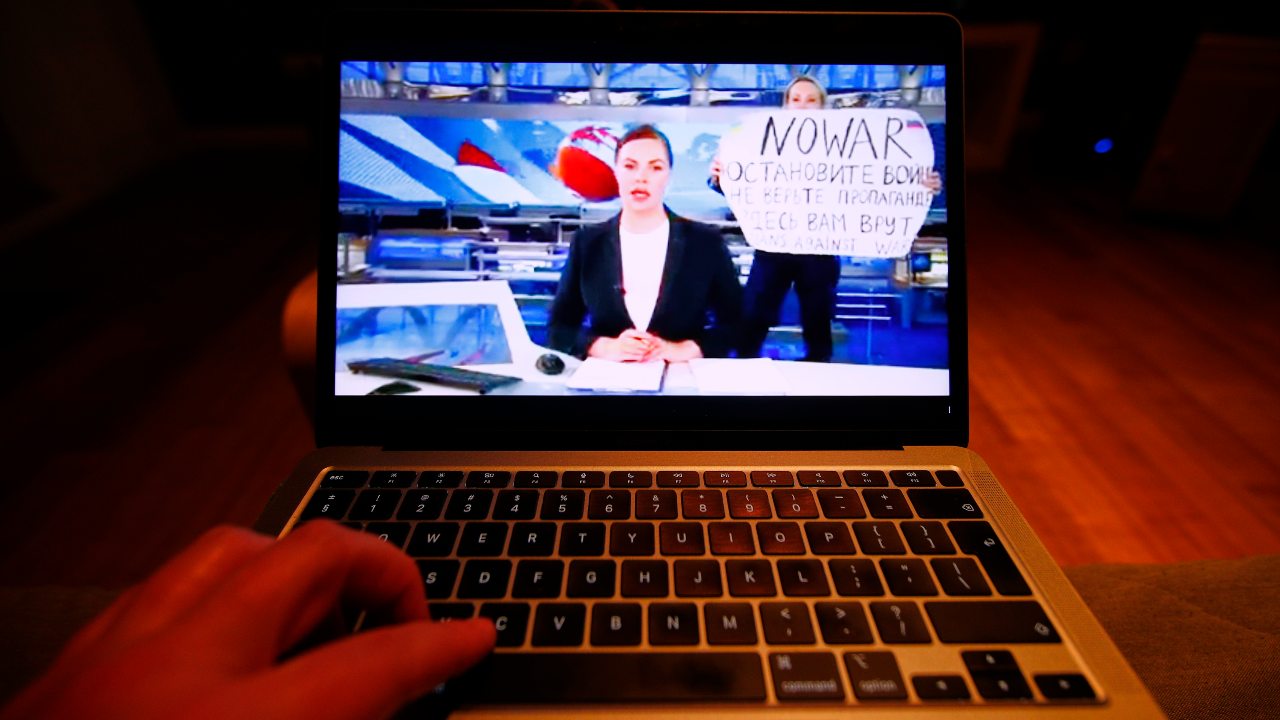

Results have been mixed, Kulitaitė said. Since the invasion began, Russia has imposed unprecedented levels of media censorship, silencing major independent broadcasters and requiring people to refer only to a “special operation” rather than an invasion. “90% of the people I reach in Russia swim in an ocean of lies and propaganda,” she said. “They don’t believe what I’m saying so they often curse me or unmatch me.” She expects to be banned at some point.

“Of course, there were also pleasant surprises when people admitted that they did not want war, but are afraid to do something and quietly support Ukraine.”

In Norway, as the BBC recently reported, one vaguely termed “computer expert” established a website enabling anyone to send emails to some 150 Russian email addresses at a time with the subject heading “I am not your enemy”. More than 22 million emails reached Russian inboxes in the space of only a few days, the outlet reported.

Like Senuta and Kulitaitė they report small-scale success – intrigued individuals wanting to learn more, extended conversations with those who don’t necessarily fully trust the Russian state’s version of events.

“I’ve sent around 500 emails so far and got around 20 replies within a day, so I’m hoping for more,” one volunteer named “Alex” told the BBC. “Most of the replies are people asking me to take them off my mailing list, but I got talking to a 35-year-old woman from St Petersburg. She told me she wasn’t sure what was going on in the conflict and wanted to know more.”

“Alex” subsequently explained how to circumvent the restrictions imposed on internet access. “I think I’ve got a friend in her now!” he said.

Aliide Naylor is the author of ‘The Shadow in the East’ (Bloomsbury, 2020). She lived in Russia for several years and now moves between London and the Baltic states, working as a journalist, editor and translator.