It represents a dramatic shift. Three months after stopping the shipment of cutting-edge AI chips to Beijing, the Trump administration has reversed course. In a blog post, the undisputed AI chip champion, Nvidia, said that the US government had approved the sale of a China-specific AI chip known as the H20.

The turnaround underlines a growing realization that US chip export controls are boomeranging. Far from isolating China, the restrictions hurt US exporters, accelerated Chinese chip innovation, and left the US vulnerable to Chinese retaliation over critical minerals.

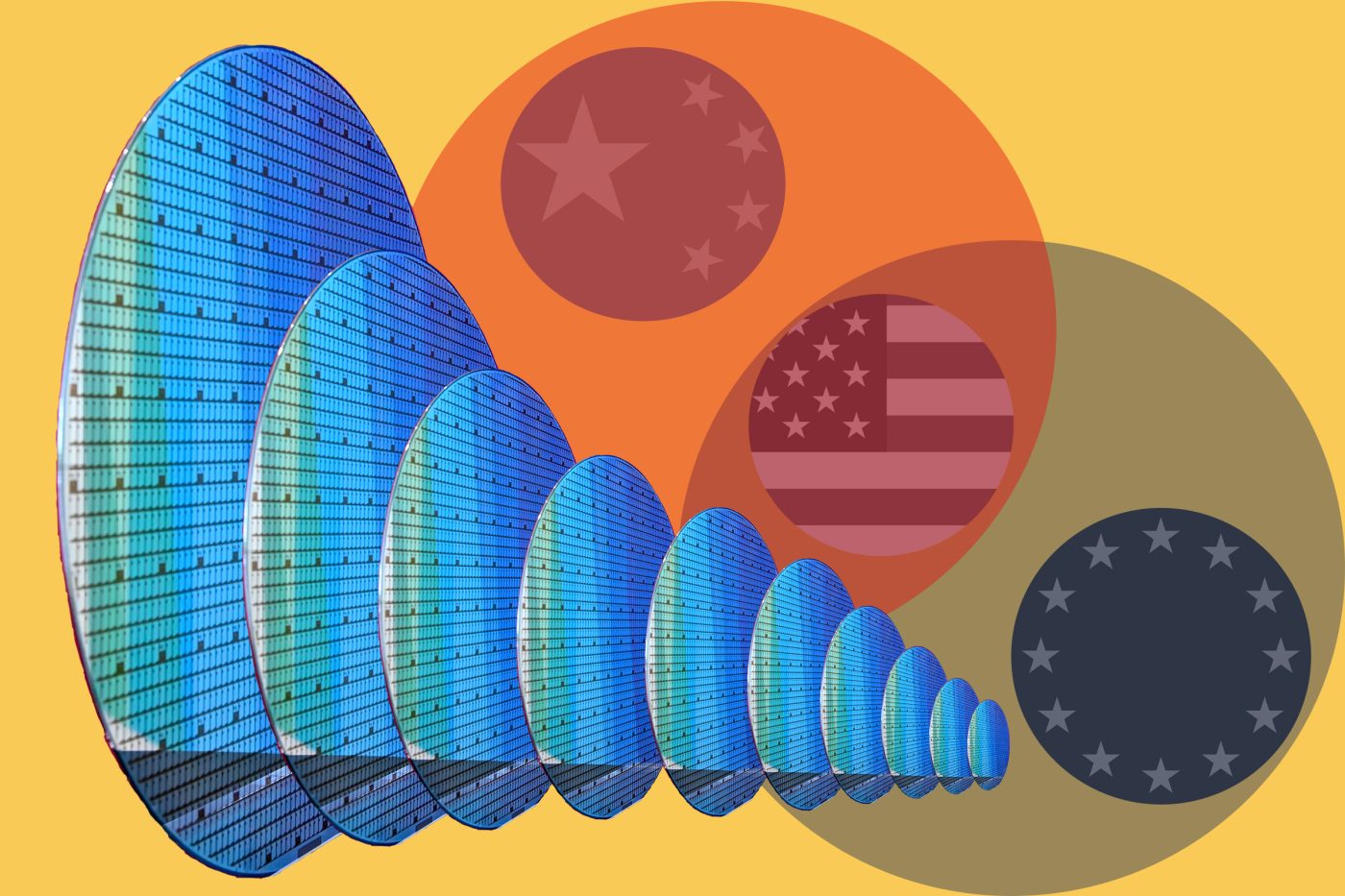

Over the past several years, the US has limited China’s access to advanced semiconductors and the machinery needed for their production. The export controls on US high-performance chips extended to foreign companies, including key allies such as the Netherlands and Japan, which are home to ASML and Tokyo Electron, essential producers of lithography tools.

The rationale was clear: by targeting the “choke points” of the semiconductor ecosystem — those few companies and countries capable of producing advanced chips — the US could delay or even derail China’s AI advancement. But this approach, while well-intentioned, faces serious limitations. It presumes a level of global alignment and enforceability that is proving difficult to sustain.

China is the world’s largest consumer of semiconductors, accounting for over 36% of global demand. In 2023 alone, China imported $349.4 billion worth of chips, making semiconductors its largest import category, surpassing even oil. This motivates Beijing to find ways around export restrictions. And it is succeeding.

One pathway is rerouting semiconductor purchases through third-party countries such as the United Arab Emirates. Persian Gulf-based joint ventures and AI startups, often backed by Chinese capital, are acquiring chips that are later re-exported, sometimes indirectly, to Chinese firms.

Simultaneously, China is accelerating its domestic capabilities. In 2023, Huawei’s surprise release of the Mate 60 Pro featured a 7nm chip designed by its in-house unit HiSilicon and manufactured by the state-supported Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation. Although Huawei used inefficient deep ultraviolet lithography equipment rather than the restricted advanced Western extreme ultraviolet machines, the achievement demonstrated that China can innovate despite sanctions.

These developments highlight a broad reality: export controls are not a long-term solution. At best, they offer a temporary head start – a brief window for the US and its allies to invest in their industrial bases and expand domestic semiconductor capacity. But as China bolsters investment, subsidies, domestic talent, and domestic R&D, the gap is closing.

The longer the controls persist, the higher the geopolitical costs will be. China has retaliated with export controls on heavy rare earth metals; it controls more than 60% of the global supply chain for many rare earth elements and more than 80% of their processing capacity. If technology decoupling deepens, China may choose to expand its restrictions on graphite, lithium, or other materials. The message is clear: chokeholds are not a one-way street.

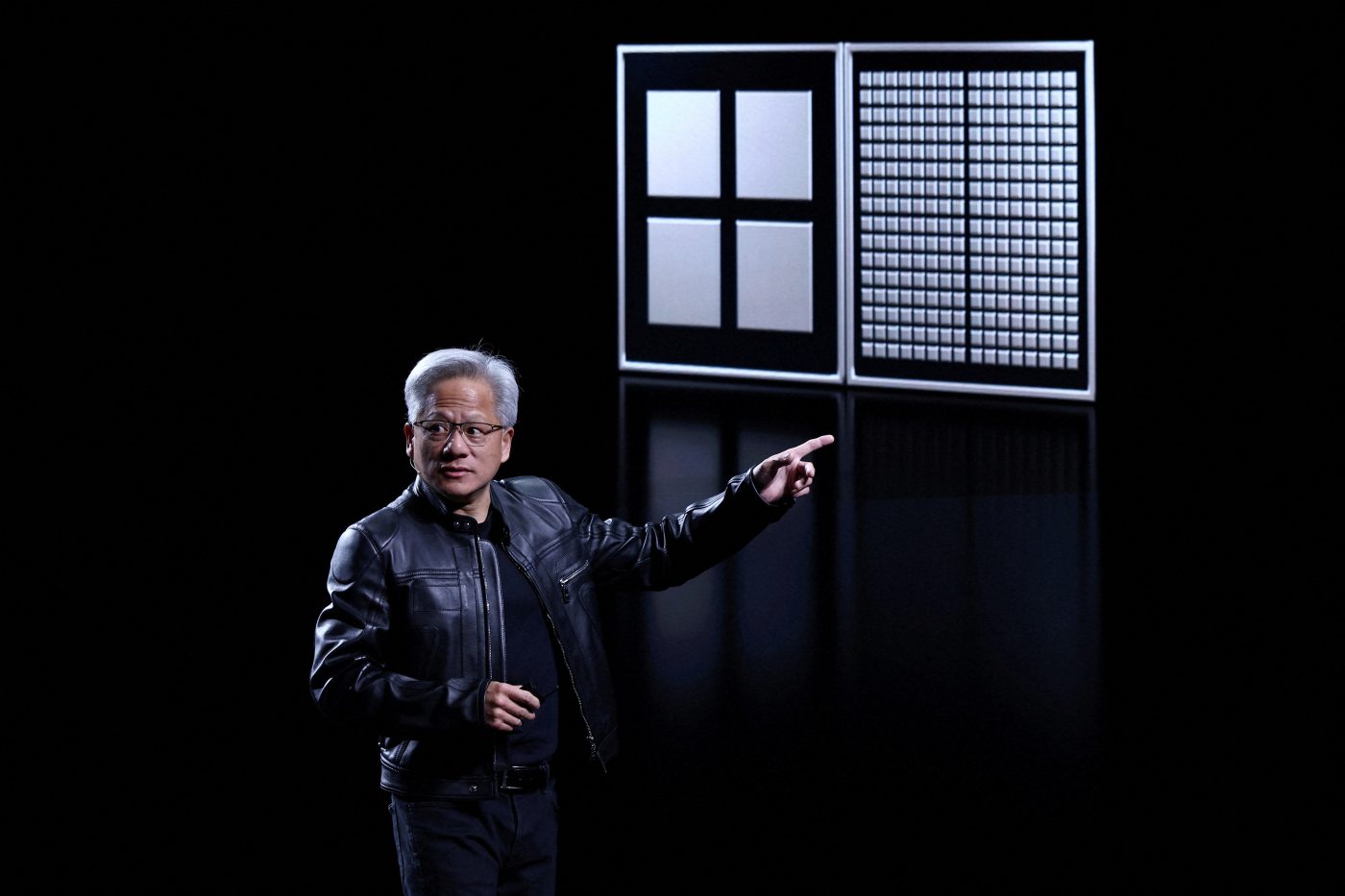

American companies also signaled discomfort with restrictions that cut them off from the lucrative Chinese market. Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang met with President Donald Trump last week and reportedly informed him that China has the potential to deliver billions of dollars in sales.

This reality calls for a reassessment — not of whether the US should remain vigilant about technology transfer, but of how it pursues that goal. Blanket export bans and long-arm jurisdiction can undermine trust, fracture alliances, and push neutral countries toward alternative systems. The US is better served by exploring a more calibrated, cooperative framework.

Instead of broad export controls backfiring, what’s needed are calibrated measures: clear guardrails on military versus civilian uses of AI chips, multilateral export licensing regimes that increase transparency, and investing in technology partnerships with emerging economies.

Just as important is a renewed dialogue with China about managing strategic advantages in a way that avoids escalation and reduces mutual dependency on unilateral actions.

There is precedent for such a strategy. During the Cold War, the US and Soviet Union maintained scientific exchanges and even cooperated on areas of mutual interest such as arms control and space.

In today’s more economically interdependent world, such engagement is not just possible — it is essential. Technological dominance does not need to be a zero-sum game.

Ultimately, export controls may buy time, but they cannot stop the tide. China’s growing technological capabilities, massive domestic market, and position in critical supply chains make it a permanent player in the semiconductor landscape. For the US, the priority must be developing a strategy of resilience, not restriction.

Elly Rostoum is a Google Public Policy Fellow with the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA). She is a Lecturer at Johns Hopkins University. You can find out more about her work here: www.EllyRostoum.com

Bandwidth is CEPA’s online journal dedicated to advancing transatlantic cooperation on tech policy. All opinions expressed on Bandwidth are those of the author alone and may not represent those of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis. CEPA maintains a strict intellectual independence policy across all its projects and publications.

2025 CEPA Forum Tech & Security Conference

Explore the latest from the conference.