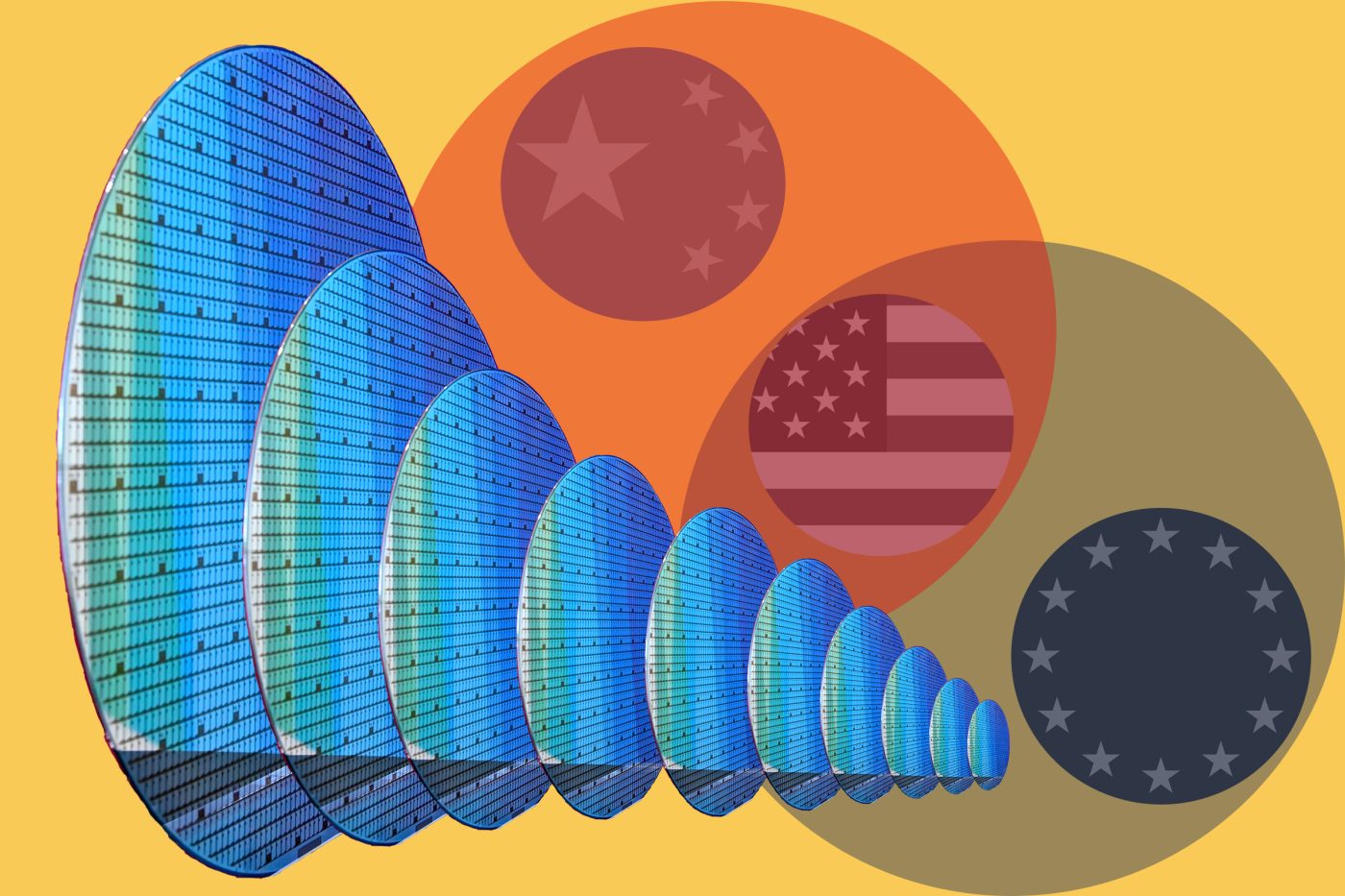

Pax Silica aims to secure a silicon supply chain, from critical minerals and energy to high-end manufacturing and software. It is framed as a response to “countries of concern,” implicitly, but not naming the target as China.

Although the idea of coordinating allied AI efforts looks solid, the Pax Silica architecture looks shaky. The criteria for participants remain unclear. Commitments to action remain vague. And America First ideology provides little reassurance for building a strong, win-win alliance.

Start with the choice of signatories. Founding signatories include Japan, the Republic of Korea, Singapore, the Netherlands, Israel, the UAE, the UK, and Australia. It’s impressive. Most qualify because they host major AI chokepoints, Japan in chemicals and optics, and Australia because of critical minerals.

But two key core manufacturing powers are absent: Taiwan and Germany. Taiwan controls advanced semiconductor manufacturing. Germany is becoming a major AI‑relevant chip hub, with Taiwan’s TSMC building a Dresden fab backed by around €5 billion in state aid. German firms such as Infineon are active in domestic expansion and have significant investments in the US market.

France and Italy also do not have seats, even though the Franco-Italian STMicroelectronics remains a major global player in power, automotive, and industrial chips, has a long record of investment in US facilities, and possesses strong design capabilities relevant to AI‑adjacent sectors such as electric vehicles and edge computing.

As with Germany, their apparent relegation to the EU “guest” category suggests that the alliance is not about rewarding existing industrial contributions, but about whose foreign and security policy aligns with Washington. Political trust and perceived strategic alignment are preferred over pure technological heft.

Although other participants, such as Singapore and Israel, are AI leaders, neither holds a significant chokepoint in the AI stack. Other key allies are also missing, including Canada and the European Union itself — both targets of Washington’s ire.

There are contradictions in US policy. The US decision to allow NVIDIA’s sale of H200 chips to China for a 25% fee on those exports, while demanding that partners coordinate export controls and investment screening, “reads as selective accommodation,” argues Pablo Chavez, an Adjunct Senior Fellow with the Center for a New American Security’s Technology and National Security Program. “Discipline for the coalition, carve-outs for Washington.”

For Pax Silica to transform from a nice idea into impactful policy, it needs a clear definition of who qualifies and would be welcome as partners, and why. It needs clear responsibilities for partners. It needs to detail specific, coordinated projects.

A strong allied response is required to meet the challenge of China’s state-driven export tech juggernaut. Hopefully, Pax Silica can become that vehicle.

Christopher Cytera CEng MIET is a Non-Resident Senior Fellow with the Digital Innovation Initiative at the Center for European Policy Analysis. He is a technology business executive with over 30 years of experience in semiconductors, electronics, communications, video, and imaging.

Bandwidth is CEPA’s online journal dedicated to advancing transatlantic cooperation on tech policy. All opinions expressed on Bandwidth are those of the author alone and may not represent those of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis. CEPA maintains a strict intellectual independence policy across all its projects and publications.

2025 CEPA Forum Tech & Security Conference

Explore the latest from the conference.