The announcement of a new defense-related policy tends to moisten the palms of British military personnel. Too often, they say, it means cutting everything by 15% and irreversibly disbanding an entire capability while claiming the country is better defended.

Refreshingly, the Defence Industrial Strategy (DIS) published on September 8, makes some welcome noises. That said, rather like the UK’s government’s pledges to increase defense spending to realistic levels but only by 2035, the DIS exhibits a marked refusal to deal with some fundamental problems.

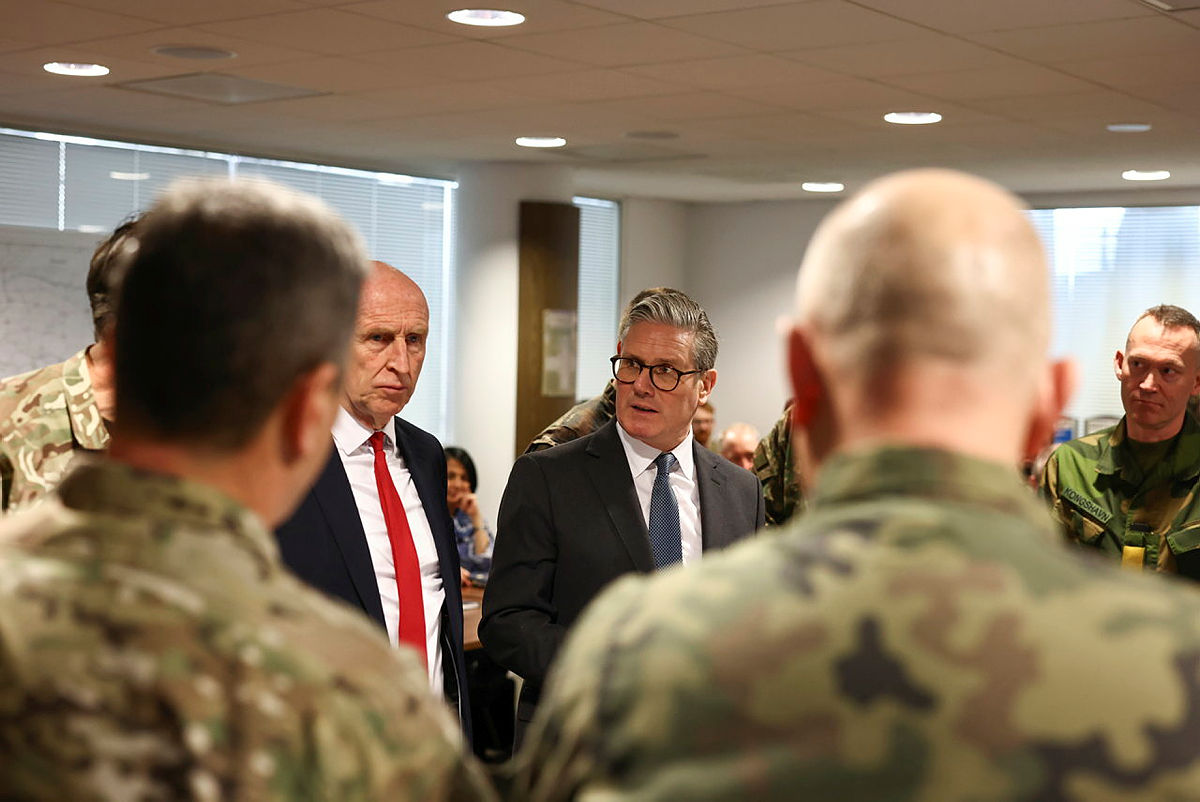

Announcing the DIS in December, Britain’s thoughtful and energetic Defence Secretary John Healey made some incisive remarks, particularly on the upside-down nature of procurement and access for genuine innovators, the scarcity of investment in defense industries, and the need to reform (particularly the pace of) procurement. As so often in the UK, it’s likely the Treasury has intervened, because it’s disappointing how little of Healey’s tone filtered down into the policy itself.

The strategy focuses on six areas of development:

- Making defense an engine for growth

- Backing UK-based businesses

- Positioning the UK at the leading edge of defense innovation

- Developing a resilient UK industrial base

- Transforming procurement and acquisition systems, and

- Forging new and enduring partnerships.

To fuel growth, the DIS identifies two key deficiencies in the workforce and investment. The establishment of dedicated Defence Technical Excellence Colleges and a Defence Universities Alliance is welcome, but there’s a lack of recognition that the skills necessary for this sector to grow and thrive are often downstream of industries the UK no longer hosts (for example, some types of steelmaking and mercantile shipbuilding), and so a skills shortage cannot be considered in isolation. Solving the shortage requires a more holistic industrial policy.

A key barrier to defense growth and innovation is the inability of small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to access Ministry of Defence contracts due to size and capability constraints. This is often solved with “thin priming,” in which a large contractor subcontracts a smaller company to do the actual work.

But this approach leaves SMEs at the mercy of the large defense companies and often creates conflicts of interest (the larger company may have a competing in-house product, for example). The DIS promises a new commercial pathway for SMEs to access MoD contracts and gives a new SME procurement annual target of £2.5bn ($3.4bn) from the MoD. Sorting this out is commendable and long overdue.

As for investment, the DIS correctly states that a key barrier are so-called Socially Responsible Investment (SRI) policies, which put defense industries off-limits for nearly all mainstream investment institutions (and internalize the Kremlin line that it’s morally disgraceful for Western countries to have arms industries at all).

This could be regulated out of existence, at least for British funds, but the DIS kicks it down the road to yet another policy paper, the Defence Finance and Investment Strategy, due next year.

Some relief comes in the form of Defence Growth Deals, which will see the government build on existing defense and related groups of firms in various regions of the country, with the participation of local and devolved authorities, and actual money.

Here, we see some joined-up thinking, linking with the government’s wider regional investment and political goals, particularly warding off separatist tendencies and the accompanying disinformation (the DIS refers to the 2024 command paper Safeguarding the Union, and talks a lot about the many defense things that happen in Scotland; it’s home to most of the UK’s surface shipbuilding capacity, for example).

However, the investment sums involved are trivial compared to the SRI logjam. Another encouraging initiative is to add defense investment to the mandate of the National Wealth Fund, the British sovereign wealth fund.

One of the lessons from Ukraine is the need to have an industrial base whose capacity can be significantly increased at short notice, particularly for expendables like ammunition. Work on this is already well underway, delays in decision-making notwithstanding, but it’s good to see the DIS taking things further with strategic investment in the nuclear deterrent, the creation of stockpiles of critical components and materials, and a renewed emphasis on flexible, scalable munition production lines across six new factories costing £1.5bn.

The government will explore new statutory powers to enable expanded production in times of need, modeled on US and French legislation, and will introduce production scalability as a key metric for assessing new procurement.

In his December press conference, Healey identified the Ajax armored fighting vehicle (AFV) as a textbook procurement disaster, in which manufacturers were given a set of over 1,000 requirements (essentially impossible for any existing platform).

No doubt Ajax will mature into a world-beating capability, but that’s rather the problem — a cheaper armored recce platform would have been fine and would already have been in full service.

Procurement is the wrong way up, as Healey noted. Instead of giving the armed forces what the market has to offer, the services are permitted to write their own menu, leading to unrealistic wish lists, lengthy procurement, wheel reinventions, vast cost overruns, and a risk of total failure.

The government’s solution is to segment procurements threefold, with separate processes and targets depending on the sophistication of the system. While this can be expected to hasten simpler requirements, it’s difficult to see how it solves the problems with higher-end acquisitions beyond arguably unrealistic target-setting.

Finally, on forging new partnerships, the DIS reads like business as usual — close cooperation with both the European Union and the United States. The sad truth is that neither looks like a particularly good cooperation partner for important defense industrial projects in terms of political risk, from German obstructionism on arming Ukraine with certain systems, as well as on Britain’s prized exports of Eurofighter Typhoon to Saudi Arabia, to the unpredictability of the Trump administration and the earlier caution of the Biden administration on Ukraine.

Outside the EU’s political structures, Britain’s ability to horse-trade this risk away is diminished. It’s difficult not to conclude that on many important systems, Britain must bite the bullet, spend the money, and simply do them alone.

Tim Sennett is a writer and podcaster based in Tallinn, Estonia. Formerly Content Manager for Mriya Report, a Ukraine-focused online radio show, he has also worked in banking, and served in the British Army as an ISTAR/surveillance operator.

Europe’s Edge is CEPA’s online journal covering critical topics on the foreign policy docket across Europe and North America. All opinions expressed on Europe’s Edge are those of the author alone and may not represent those of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis. CEPA maintains a strict intellectual independence policy across all its projects and publications.

War Without End

Russia’s Shadow Warfare

CEPA Forum 2025

Explore CEPA’s flagship event.