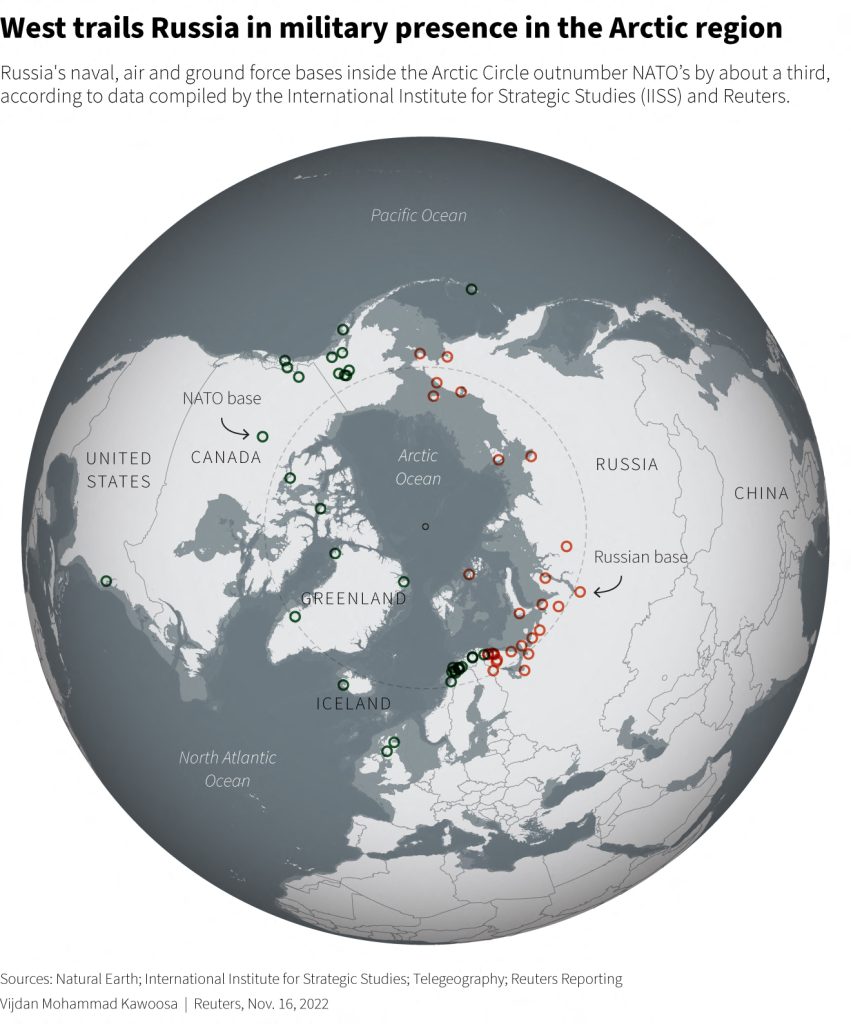

NATO’s 2011 Alliance Maritime Strategy has become obsolete. The alliance needs a fresh approach to its northern flank as Russia continues its heavy investment in military facilities in the Arctic and increasingly works with China to exploit resources and open trade routes.

A Standing Arctic Maritime group would strengthen the alliance’s naval posture in the waters around Norway and in the Greenland–Iceland–UK (GIUK) Gap, deterring Russian cruise missile submarines from attacking NATO’s economic infrastructure.

Maritime strategy during the late Cold War offers lessons for today’s landscape, foremost among them the need to enhance its naval presence and maritime surveillance while holding larger naval exercises on the alliance’s northern flank.

The US Maritime Strategy of the 1980s saw control of the waters around Norway as pivotal for a possible Third Battle of the Atlantic.

Vice Admiral Hank Mustin, who was involved in the planning, said NATO strategists realized their forces would have to “go up into the fjords in Norway, and from the shelter of the fjords we [could] attack, not only the Soviet fleet and keep it penned up in its bastions, but the Soviet facilities in Kola.”

Based on those assumptions and the associated need to deploy two or three Carrier Strike Groups to the region around Norway, the US organized a number of exercises with NATO navies, such as Ocean Safari and Northern Wedding 1986. These were much larger scale than those held today.

The accession of Sweden and Finland adds important naval assets to NATO’s main naval exercises and its Standing Maritime Groups. Sweden’s Visby-class corvettes and Blekinge-class diesel-electric submarines, along with Finland’s Pohjanmaa-class corvettes, currently under construction, will boost its naval posture in the Baltic.

Beyond the individual capabilities of the Nordic nations and the various exercises currently held throughout the year, NATO needs a stronger collective approach based on increased naval presence. A stronger posture would enable its navies to obtain local sea control and exercise it when needed.

To do so, allies should explore the option of establishing an Arctic Standing Maritime Group, assigned to the waters around the GIUK Gap, the Norwegian Sea, and the Barents Sea, to strengthen their posture in relation to Russia’s Northern Fleet.

It could be integrated into current exercises, such as Dynamic Mongoose or Nordic Response, to bolster naval capabilities and interoperability in the High North. The group should be resourced with a balanced combination of larger surface combatants, such as destroyers and frigates, and smaller patrol vessels, fast attack craft, and icebreakers to escort them.

While necessary, the increased naval presence would also create operational challenges. Arctic environmental conditions, such as low temperatures, snow, sleet and freezing rain, fog, and abnormal magnetic conditions, would all affect the performance of warships and their crews.

Communications in high latitudes are also degraded by electric storms and ionospheric disturbances, and special procedures are needed to ensure the operation of electronic equipment at temperatures lower than -2ºC, according to the NATO Naval Arctic Manual. These and other aspects would need careful consideration.

With the resurgence of the submarine threat in the Norwegian and Barents seas, and the prospect for a navigable Arctic in the future, NATO’s northern flank will become an increasingly important area for maritime operations.

In light of this, placing all the Nordic countries under the same Joint Force Command, rather than having them divided between Norfolk, Virginia, and Brunssum in the Netherlands, should also be considered.

“Norfolk should cover the entire Cap of the North. It makes sense,” Karsten Friis, a defense analyst at the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs, said in August. “It is unthinkable to cover Finnmark without the entire Cap of the North militarily.”

NATO navies must deter Russian submarines from venturing into the Atlantic, from where they would be able to attack strategic land targets in the European and the American continents, including reinforcement convoys in times of crisis and war. Doing so will require a new and refreshed strategic approach.

An increased naval presence, with an Arctic Standing Maritime Group and larger naval exercises at its core, as well as an updated Alliance Maritime Strategy to guide their larger maritime efforts, will be fundamental to modernizing NATO’s naval deterrent.

Gonzalo Vázquez is a graduate student in War Studies at King’s College London, and a junior analyst with the Center for Naval Thought at the Spanish Naval War College. He previously worked as an Intern at the NATO Crisis Management & Disaster Response Center of Excellence in Bulgaria.

The views expressed are his own.

Europe’s Edge is CEPA’s online journal covering critical topics on the foreign policy docket across Europe and North America. All opinions expressed on Europe’s Edge are those of the author alone and may not represent those of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis. CEPA maintains a strict intellectual independence policy across all its projects and publications.

War Without End

Russia’s Shadow Warfare

CEPA Forum 2025

Explore CEPA’s flagship event.