EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

During the last year of the Trump administration, the U.S. broke too many eggs in the Serbia-Kosovo dialogue without making an omelet. Following the landmark transition from President Donald Trump to President Joe Biden, and in the context of the September 4, 2020, agreement between Serbia and Kosovo brokered by the Trump administration in Washington, D.C., it is important to reassess U.S. mediation efforts in the Serbia-Kosovo dispute. This policy paper will ask how “ripe for resolution” the dispute is and whether U.S. and other diplomatic efforts are pushing it toward resolution.

Normalization of relations between Serbia and Kosovo should ideally include:

- Serbia’s recognition of Kosovo’s independence.

- A solution to issues of insecurity between the two entities.

- Guarantees and promotion of minority rights.

- Some form of transitional justice.

This paper examines the following factors and their role in promoting and preventing normalization of relations between Serbia and Kosovo.

- The key issues underpinning the dispute.

- The main players (adversaries, influencers, and mediators).

- Contextual factors.

- Strategies available to the adversaries in pursuit of their goals.

The main finding of this research paper is that the Serbia-Kosovo dispute is not ripe for resolution:

- The two top issues, sovereignty and security, are notoriously difficult to resolve. The adversaries are not ready to end the dispute, at least not under current conditions and in a manner that will produce a prompt and comprehensive agreement.

- The main influencers, Russia and China, are undermining the normalization process. Russia is set on protecting its energy interests in Serbia and keeping the Western Balkan countries out of the EU and NATO. China’s goal is not necessarily to undermine the normalization process, but its developing relationship with Serbia may compromise Serbia’s ability to integrate into the EU, which in turn makes it more difficult for the EU to use prospective membership as a carrot for normalization.

- Divisions within the EU mean that the dialogue lacks a clear, explicit goal — sovereignty for Kosovo — which weakens the process.

- Trump’s special envoy for the Serbia-Kosovo dialogue, Ambassador Richard Grenell, undermined the chances for a comprehensive agreement by splitting the dialogues into one led by the U.S. on economic matters and another led by the EU on political issues. A package deal jointly coordinated with the EU stands a much greater chance of succeeding than Grenell’s fractionating approach.

Given that a comprehensive agreement between Serbia and Kosovo is not in sight, this paper recommends that the U.S. return to the long game in Serbia and Kosovo by:

- Maintaining the position of U.S. special envoy for the Western Balkans.

- Protecting Kosovo’s independence and territorial integrity.

- Supporting liberal democracy in the Balkans.

- Acting in tandem with the EU and U.K.

1. INTRODUCTION

The dispute between Serbia and Kosovo is often referred to as a “frozen conflict,” but that term encourages a false sense of security.1 As the fighting over Nagorno-Karabakh in 2020 showed, frozen conflicts can heat back up. On May 12, 2020, long before the White House talks in September and the more recent European Union-led initiatives that brought Serbs and Kosovars to the table, Balkans expert Janusz Bugajski noted that although the Serbia-Kosovo dialogue “hasn’t died, it smells.”2 Bugajski’s words still ring true.

In the mid-1990s, the U.S. built credibility in the Balkans by playing a central role in ending some of the main conflicts and halting genocide. Its success was so great that some experts talk about U.S. “path dependency” in the Balkans, especially in peacemaking.3 During the last year of the Trump administration, however, some inside the U.S. State Department and among close European allies increasingly criticized the U.S. approach to the Serbia-Kosovo dialogue.4 The Biden administration has an opportunity to resituate U.S. foreign policy in the Balkans in a manner that is bipartisan and geared toward serving long-term U.S. interests.

The primary question guiding this research is whether the Serbia-Kosovo conflict is “ripe for resolution.”5 Peace studies scholar William Zartman coined the term “ripeness” to describe the timing of peacemaking.6 It is based on the assumption that parties to a conflict will make peace only when a range of conditions favor such an outcome. In the absence thereof, mediators will struggle to bring a dispute to a halt, even when the mediator is seemingly powerful. The final section explores policy recommendations relevant to U.S. policymakers.

2. BACKGROUND

The crumbling of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY), which existed from 1963 to 1992, began in Kosovo. SFRY consisted of six republics — Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia — and two autonomous entities inside Serbia, Vojvodina, and Kosovo. In 1987, the then-president of the League of Communists of Serbia, Slobodan Milošević, made a landmark speech to a crowd of angry Serbs in Pristina declaring, “No one should dare to beat you.”7 His speech was misleading as Kosovo Albanians in the 1980s were the prime victims of systematic discrimination.8 Nonetheless, Milošević actively promoted the dangerous process of “othering,” and henceforth, ditched Yugoslavism for Serbian nationalism, sparking a series of violent conflicts.9

By 1992, Milošević was at the helm of rump Yugoslavia, which consisted only of Serbia and Montenegro. His promotion of Serbian nationalism and “Greater Serbia” — that is, uniting all Serbs in one territory, including those outside Serbia — led to increased discrimination against non-Serbs, some of whom suffered mass atrocities, including genocide. Consequently, Kosovo Albanians began to push for the independence of Kosovo.

Key events in the run-up to Kosovo’s declaration of independence

1987 (April 24): Slobodan Milošević delivers a speech in Kosovo that further incites ethnic tensions between Serbs and Kosovar Albanians.

1989 (May 8): Milošević becomes president of Serbia.

1990 (January 20-22): Slovenian, Croatian and Macedonian delegates abandon the last Congress of the Communist League of Yugoslavia and the party is dissolved.

1991 (June 26): Slovenia and Croatia declare independence.

1991 (June 27): Start of Ten-Day War in Slovenia, which lasts until July 7, 1991.

1991 (September 25): Macedonia declares independence.

1991 (October 8): Croatia declares independence from Yugoslavia.

1991-1995: Croatia enters a four-year war with the Yugoslav army.

1992 (March 3): Bosnia declares independence.

1992-1995: The Bosnian war begins April 6, 1992, and ends on December 14, 1995. Bosnian Serbs with the support of Milošević’s rump Yugoslavia commit mass atrocities against non-Serbs.

1994 (April): NATO carries out the first airstrikes in its history against Bosnian Serbs targets.

1995 (December 14): The Dayton Accords are signed by the leaders of Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Croatia, putting an end to the Bosnian war. The issue of discrimination against Kosovo Albanians does not feature in Dayton’s agenda.

1996: The Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) launches sporadic attacks against Serbian authorities in Kosovo in response to Serbia’s suppression of student and ethnic movements in Kosovo.

1998 (March 31): UN Security Council Resolution 1160 condemns Yugoslavia’s excessive use of force, imposes economic sanctions and bans arm sales to Serbia.

1998 (June 23-24, 1998): Richard Holbrooke meets with Milošević and travels to Kosovo to talk directly with KLA commanders.

1998 (August): Serbian forces step up their offensive, attack KLA and Kosovar villages.

1999 (January 15): Serbian security forces kill 45 Kosovo Albanians in the Račak massacre.

1999 (March 24): NATO begins bombing Serbian targets in response to ethnic cleansing of Kosovo Albanians.

1999 (June 10): NATO bombing ends. The UN Security Council adopts Resolution 1244, which authorizes an international civilian and military presence in rump Yugoslavia and establishes the UN Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK).

1999 (June 20): Serbs complete withdrawal from Kosovo and NATO Secretary General Javier Solana formally ends the alliance’s bombing campaign.

2008 (February 17): Kosovo declares independence from Serbia.

At first, Kosovo Albanians largely followed Ibrahim Rugova, the pacifist leader of Democratic League of Kosovo (LDK). But in the face of increasing oppression, many Kosovo Albanians turned to the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) to wage an armed struggle against Serbia in their quest for independence. War with Serbia escalated in February 1998 and lasted until June 11, 1999.10 In Kosovo, as in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbian forces committed ethnic cleansing and mass atrocities. In 1998 and 1999, the Kosovo conflict claimed the lives of about 10,000 Kosovo Albanians and displaced 900,000 people, nearly half of the population. Milošević’s atrocities were halted by the KLA with significant air support from NATO.11

Kosovo declared independence on February 17, 2008. While the U.S. and most European states recognize Kosovo’s sovereignty, the most important actors opposing Kosovo’s independence include Serbia, Russia, China, and five EU member states.

There are two main tracks of Western diplomacy. The first is the “Belgrade-Pristina dialogue,” the EU process that kicked off in March 2011 with the ultimate goal of normalizing relations between the two states.12 The mediation process started off as a dialogue about technical measures to facilitate the exchange of goods and people, but it rapidly evolved into a political dialogue, which led to, among others, the 2013 Brussels Agreement. From late 2018 until fairly recently, the EU dialogue was largely at an impasse. Miroslav Lajčák, the EU special representative for the Belgrade-Pristina dialogue since April 2020, has breathed some life into it by facilitating more contact sessions between the adversaries. At the same time, high-level meetings have not yet produced a major breakthrough in the normalization process.

The second track is the U.S.-led “Serbia-Kosovo dialogue.” In August 2019, some Balkans watchers were excited by the appointment of Matthew Palmer as U.S. special envoy to the Western Balkans.13 Palmer is an old hand in the Balkans and the first U.S. special envoy to the region since the 1990s. Then in September 2019, the White House named Richard Grenell, who was then the U.S. ambassador to Germany, as special presidential envoy for the Serbia-Kosovo talks. Along the way, Grenell began his own diplomatic initiative, and instead of supporting the EU’s Belgrade-Pristina dialogue, the U.S. opened up the Serbia-Kosovo dialogue. According to a high-level EU official, the U.S. initiative was “not coordinated” with the EU.14

The initial hype about U.S. re-engagement in the Balkans faded during the last few months of the Trump administration. Gorana Grgić, a Balkans expert, criticized the U.S. for squandering “long-term investments” in the region in exchange for short-term foreign policy victories for Trump.3 The U.S. stood accused of supporting controversial “land swap” deals between Serbia and Kosovo; of bullying Kosovo’s then-prime minister, Albin Kurti, into dropping tariffs against Serbia, leading to a vote of no confidence in him; and of sidelining the EU.15

In the context of increasing diplomatic efforts to normalize relations between Serbia and Kosovo, and given the Trump-Biden transition, how likely is it that the dispute will be resolved under current conditions?

3. KEY FACTORS DETERMINING RIPENESS

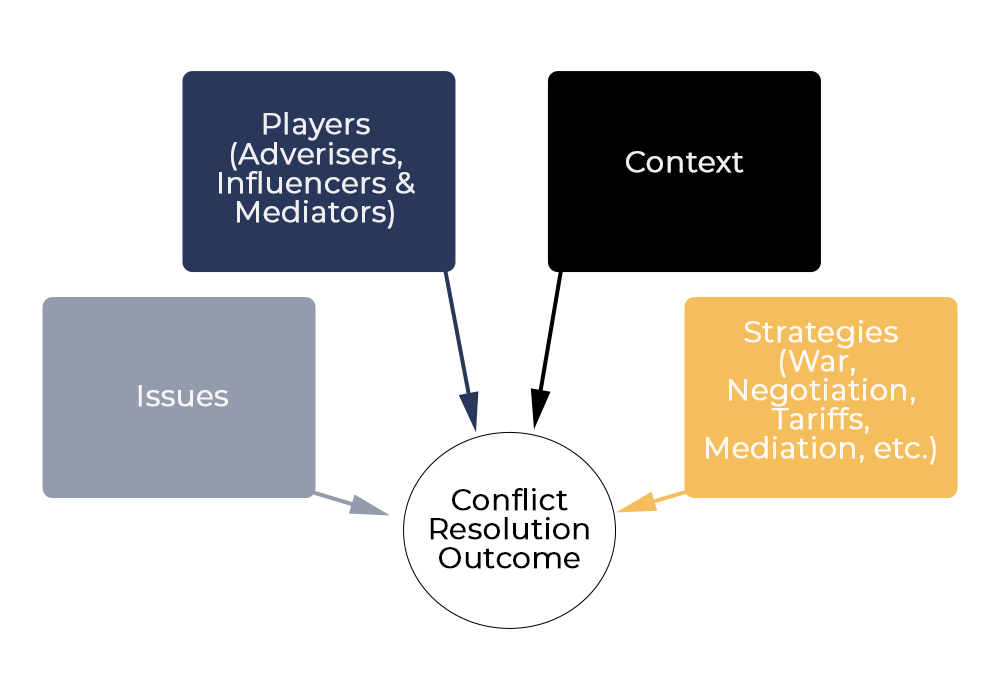

The outcome of the Serbia-Kosovo dialogue depends chiefly on the issues, the players (adversaries, influencers, and mediators), the context, and the strategies of the adversaries.16

Figure 1: Determining Conflict Resolution Outcomes

3.1 Issues

At the heart of the dispute are five fundamental issues: sovereignty, security, minority rights, transitional justice, and economic issues. A comprehensive agreement should ideally address all of them.

First, on the issue of sovereignty, the Serbian government maintains that Kosovo is part of Serbia, while Kosovo’s government asserts that it is independent. Second, and flowing from the issue of sovereignty, the Serbia-Kosovo dispute is connected to security. In the 1980s and 1990s, Kosovo Albanians increasingly faced an existential threat following systemic discrimination and ethnic cleansing, which eventually led to the Kosovo War in 1998 and 1999.17 While guns are no longer blazing between Serbs and Kosovars, a sense of insecurity will remain until Serbia relinquishes its claim to Kosovo’s territory. As Kosovo’s former foreign minister, Glauk Konjufca, has said, Serbia will fight for Kosovo for as long as its constitution defines it as part of its territory.18

Third, and closely linked to security and sovereignty, are issues about ethnicity and minority rights. Serbs claim that Kosovo Serbs are discriminated against, which is partly why they are pushing for an Association of Serb Municipalities (ASM),19 while non-Serbs complain about discrimination in Serbia.20 For example, Mayor Shqiprim Arifi of the Albanian-dominated Preševo municipality in Serbia blames systematic discrimination for the roughly 50 percent unemployment rate among his constituents, compared with the national average of about 13 to 15 percent.21

Fourth, many Kosovars, convinced that Serbia has not faced up to serious crimes it committed during the Kosovo war, are demanding some form of transitional justice.22 That could range from cooperation on missing persons to reparations, as part of a normalization package with Serbia.23

Finally, although economic issues — such as disputes over ownership of natural resources or territorial delineation impacting on transportation routes — have not been central to the onset of the dispute, they could grow in importance, especially given the impact of covid-19 on the Western Balkans. Economic matters are also closely linked to prospective regional cooperation, which will remain constrained in the absence of agreement on political normalization.

If normalization between Serbia and Kosovo requires that all the issues are included in a comprehensive agreement — sovereignty, security, ethnicity, minority rights, transitional justice, and economic issues — and then implemented, then U.S. and EU mediators are in for a rough ride. As one Western diplomat noted prior to the Washington agreement in 2020, the U.S. can “strongarm” Kosovo and Serbia into a limited deal, but that will not resolve the underlying dispute.24 However, if the U.S. seeks to eventually integrate Serbia into the EU and Kosovo into the EU and NATO, it will “need to take collective action” with the Europeans.25

In fact, Jacob Bercovitch and Allison Houston’s empirical study of 137 mediated disputes determined that conflicts about sovereignty and security, the two top issues defining the Serbia-Kosovo dispute, are notoriously hard to resolve with a success rate of only 44.7 and 40.7 percent respectively.6 And that’s even with the bar set low: Bercovitch and Houston’s study defines a successful outcome merely as reduced violence or securing an agreement.26 For civil wars between 1940 and 1990, only one out of three ended in a peace agreement that was implemented successfully.27 In short, brokering a comprehensive agreement will be hard, and implementing it will be even harder. Of the 33 agreements the EU has brokered between Serbia and Kosovo, implementation has been slow or spotty.28

3.2 Players

The Serbia-Kosovo dispute brings together three sets of players: adversaries, influencers, and mediators. Adversaries are the direct parties to the dispute, influencers have some form of influence over the adversaries and mediators are actively seeking a resolution to the dispute.

3.2.1 Adversaries

The primary factor determining the outcome of any conflict is the willingness of the adversaries to resolve it.29 To gauge how willing Serbia and Kosovo are, it helps to consider their political situations, stated positions, and actual goals for an agreement.

The following two subsections will focus on Serbia’s and Kosovo’s public positions — which may differ from their intentions — and explore what their leaders require from “normalization.” The section on strategies will identify how the two adversaries intend to pursue their goals.30

3.2.1.1 Serbia

Darko Brkan, president of the Zašto Ne (Why not?) nongovernmental organization in Sarajevo, said the success of the Serbia-Kosovo dialogue will hinge on “how far Serbia is willing to compromise” on recognizing Kosovo’s sovereignty.31 More specifically, given his dominant role in Serbian politics, President Aleksandar Vučić holds the key to the outcome. Will he be willing to take the leap toward full normalization?

Vučić is a “hardcore traditional realist” who “understands power,” according to Marko Savković, executive director of the Belgrade Fund for Political Excellence.32 On June 21, 2020, Vučić’s Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) won the election by a landslide, or some 190 of the Serbian parliament’s 250 seats. Igor Novaković, research director of the Belgrade-based International and Security Affairs Center, notes that Vučić depends on a “clientelist network” to maintain his power.33

It is thus noteworthy that SNS, which was only established in 2012, has a membership base of 750,000 — nearly 10 percent of the entire population — making it the largest political party in Europe (if one excludes Russia and Turkey).34 By comparison, if 10 percent of Russians signed up to President Vladimir Putin’s United Russia, it would have a membership of 14.5 million (instead of 2.1 million).

Several people interviewed for this paper likened Vučić to Hungary’s controversial prime minister, Viktor Orbán.35 Serbia under Vučić is experiencing “the rise of centralization of power and a backsliding of democracy.”36 Over the last few years, he has led Serbia closer to a semi-authoritarian state.19 In the most recent edition of its flagship Nations in Transit report, Freedom House concluded that for the first time since 2003, Serbia can no longer be considered a democracy.37

Serbian analyst Stefan Vladisavljev said Vucic’s advantage is that his “radical” leaning in the past gives him “legitimacy among the right wing.”36 Unlike previous Serbian leaders, he thus has more leeway to make some form of a deal with Kosovo without giving Serbian radicals and other spoilers an opening to say he sold out. Still, it is hard to pinpoint what Vučić means by “normalization” of relations with Kosovo. A large part of it has to do with the fact that he himself may be “torn” about this issue.38

Vučić’s public position, at least to the international community, is that he wants to participate in the dialogue to normalize relations with Kosovo and to bring Serbia into the EU. His EU aspirations seem key, given that they depend on normalizing relations with Kosovo. In fact, EU membership is often posited as an essential carrot to get Serbia to recognize Kosovo’s sovereignty.39

Some Serbian analysts argue that Vučić accepts that Serbia cannot “reimpose” itself over Kosovo.32 The president understands that the Serbia-Kosovo dispute creates obstacles to regional cooperation and presents impediments to Kosovo Serbs. Others say Vučić has even started to prepare the Serbian public to accept that some hard choices will have to be made about Kosovo.33 Even one high-level Kosovo official said, “Serbia is serious about normalization, as Vučić wants Serbia to be part of the EU.”40

Savković, of the Belgrade Fund for Political Excellence, said that although the state-controlled Serbian media less frequently portray Kosovo Albanians as “the enemy,” they still freely use the term “Šiptar,” an epithet equivalent to the n-word in English.32 The message is that Serbs “can’t live with these people” so there becomes a “need to demarcate” the border between Serbia and Kosovo along the lines of “Trump’s wall.”6 Vučić and Kosovo’s former president, Hashim Thaçi, once saw the so-called “land swap” between Serbia and Kosovo as the key to normalizing relations. Kosovo would have ceded areas north of the Ibar river in Mitrovica with majority-Serb populations to Serbia, in return for areas in the southern Preševo Valley (Serbia) with majority-Albanian populations.40

Additionally, some observers argue that despite his considerable power, Vučić still has to color within the lines. International negotiation is often described as a “two-level game” in the sense that parties have to negotiate with the other side as well as with their own constituencies.41 In May 2019, during a tête-à-tête with the former U.S. Army commander in Europe, retired Lieutenant General Ben Hodges, Vučić said he would be considered a “traitor” if he recognized Kosovo.38 He faces a lot of pressure from a variety of groups, including the Orthodox Church, war veterans, and the Kremlin. The Serbian public at large views Kosovo as “the Serbian Jerusalem,” sacrosanct.42 This strong emotional attachment to the territory means that the matter is not a rational, transactional issue.

As mentioned earlier, Vučić says he wants to launch Serbia into the EU.43 It is a popular idea that resonates with the Serbian public, as long as EU membership is not tied to Kosovo’s recognition. Serbian analysts describe the recognition of Kosovo as political suicide.36 A 2019 poll by the Center for Social Dialogue and Regional Initiatives found that although 55 percent of respondents supported the Serbia-Kosovo dialogue, only “14.1% of [Serbs] would agree to support recognition of Kosovo’s independence if it were a precondition for Serbia’s EU membership, while 71.7% opposed it.”44 Vučić is known for paying close attention to public opinion. In a June 2020 interview, he told Reuters: “In reply to a possible offer [to Serbia] to recognize Kosovo and that Kosovo enters the UN, and we receive nothing in return, except EU membership, our answer would be ‘no.’ ”45

Still, analyst Bodo Weber of the Democratization Policy Council said that given his influence over Serbian society, “Vučić can change public opinion in six months if he wants to.”46 Accordingly, Vučić is not merely a thermometer reflecting the public’s mood, but rather he is a thermostat leader with the ability to adjust their attitudes to accept Kosovo’s recognition. Preparing the Serbian public for a comprehensive deal is important, given that the Serbian constitution stipulates that recognition of Kosovo would require a referendum.47

Žarko Trebješanin, a prominent Serbian psychologist, describes Vučić as “narcissistic,”48 which could complicate deal-making as Vučić seeks a face-saving settlement that the Serbian public would accept and that would make him look like the winner. Although the land swap idea was once seen as a silver bullet, Kosovo will not accept it, especially now with Thaçi out of the picture. More recently, Vučić started hinting that the formation of the ASM — a self-governing association of Serb-majority municipalities in Kosovo — as per the Brussels Agreement may suffice to facilitate further dialogue. However, the establishing of the ASM was declared partly unconstitutional by Kosovo’s Constitution Court in December 2015, leading to a deadlock in the negotiations.49

Konjufca, the former foreign minister for Kosovo, said he believed Vučić was open to the idea of “two Germanies,” in which Serbia would not recognize Kosovo but they would merely coexist.18 That arrangement, though, would not necessarily encourage the kind of recognition that Kosovo needs from other governmental organizations, including the UN, EU, and NATO, and therefore would not resolve territorial and security issues between the two entities.

To summarize this section, a comprehensive agreement between Serbia and Kosovo is going to be hard to achieve, especially if it hinges on Vučić’s willingness to compromise.

3.2.1.2 Kosovo

Kosovo has recently experienced two fundamental changes that will affect the negotiations: Thaçi’s resignation as president and the shift of political power following the February 2021 parliamentary election.

Thaçi’s resignation on November 5, 2020, as president following his indictment by the Balkan war crimes tribunal in The Hague was an earthquake in Kosovo’s political landscape. The undisputed dominant political figure in Kosovo, Thaçi was intimately involved with the dialogue from 2011 until his indictment in June 2020. Researcher Teuta Kukleci with the Peace Research Institute Oslo said many Kosovars thought of Thaçi as someone with “war credentials,” and it was akin to “treason to go against him.”50

Consider the fate of Thaçi’s former prime minister, Albin Kurti, who defied his wishes. Konjufca said Thaçi summoned Kurti to his office after the prime minister assumed power in 2020 and tried to convince him that “border corrections,” a euphemism for land swaps, would help normalize relations between Serbia and Kosovo “within a week.”51 Given that Kurti’s party, the Self-determination Movement (LVV), campaigned against land swaps during the 2019 election, Kurti objected to the idea. Thaçi then mobilized against the prime minister, who was removed after serving for a mere 51 days. Thaçi (temporarily) maintained his primacy in the negotiations. Following Kurti’s ousting, Balkan watchers also blamed the U.S. for the collapse of his government on June 3, 2020, shortly after covid-19 escalated.52

Kurti’s successor as prime minister, Avdullah Hoti, came not from LVV, but from its erstwhile coalition partner, the Democratic League of Kosovo (LDK), which before the February 2021 parliamentary election was the second-most popular party in Kosovo’s Assembly. LVV’s leaders felt a deep sense of betrayal by the LDK, which they felt had “sabotaged the government of Albin Kurti,” according to Kreshnik Ahmeti, LVV’s secretary of external and international relations.53 Consequently, LVV refused to take part in the Serbia-Kosovo dialogue with Hoti, whom it deemed “illegitimate.”6

LVV’s absence in the dialogue following Kurti’s removal mattered: With 29 seats in Kosovo’s 120 member parliament before the February 2021 election, it had only to team up with a handful of other lawmakers to block the two-thirds majority that international agreements need for ratification in Kosovo.54

Kurti’s short stint in office was somewhat extraordinary but nonetheless an accurate reflection of the instability of Kosovo politics. Aside from the incoming prime minister, the country has had four prime ministers since 2014, from three different political parties: Isa Mustafa from the LDK (2014 to 2017); Ramush Haradinaj from the Alliance for the Future of Kosovo (AAK) (2017 to 2019); Kurti from LVV (February 3, 2020, until June 3, 2020); and, most recently, Avdullah Hoti, also from the LDK (June 3 to present), who will most likely hand back the torch to Kurti. Each brought different interests to the negotiation table, which made Kosovo an unstable party.6

To add to the complexity, Kosovo’s Constitutional Court ruled that Hoti’s government was “illegal,” which meant Kosovo had to hold early elections on February 14, 2021.55 In mid-January 2021, Kurti and Vjosa Osmani announced they would join forces to compete in the election. Shortly afterward, Kurti was barred from running in the parliamentary election because he had been convicted of a crime — using teargas in the Assembly — within the last three years.56

Osmani, the chairwoman of the Assembly and, since Thaçi’s resignation, the acting president, is a popular figure. She was removed from the LDK’s leadership in June 2020 for opposing a motion of no confidence against the Kurti-led government. Upon becoming acting president, Osmani asked for the dialogue to be postponed to provide space to Kosovo’s parties to forge a unified front.57

At the time of writing, votes are still being counted, but LVV is on track to secure approximately 48 percent of the vote. While those results may fall short of the 50.83 percent needed to form an exclusively LVV cabinet, they will put Kurti and Osmani in strong positions.58 The duo’s pre-February election pact was that Kurti will become prime minister once again while Osmani will be the country’s next president. Kosovo’s Assembly elects the president, who has the prerogative to appoint the candidate for prime minister following consultation with the majority party or coalition in the Assembly.59 Despite being barred from running for parliament during the February 2021 election, Kurti will most likely reclaim the position of prime minister. His exclusion from government could cause political instability.

LVV’s February 2021 electoral victory represents a major shift in the political landscape in Kosovo. PDK and LDK’s poor performance demonstrates that the country is ready for change. As researcher Visar Xhambazi of Kosovo’s Democracy for Development Institute notes, unlike some of the old establishment parties, LVV’s reputation is not tarnished by corruption and criminal scandals.60

Kurti has said his domestic agenda — “jobs and justice” — will take priority over dialogue with Serbia.61 But as Xhambazi notes, given the significance of the dialogue, Kurti cannot put the talks on the back burner.60 It is thus not a question of whether, but how, LVV will engage in the dialogue.

“The overwhelming victory of [LVV] marks the beginning of a more assertive Kosovo in negotiations with Serbia,” according to Sidita Kushi, an assistant professor of political science at Bridgewater State University in Massachusetts. “Unlike previous old-guard politicians who were more malleable to Western demands, Kurti has made it clear that he will continue talks under conditions of reciprocity and the goal of mutual recognition — meaning that greater concessions and an ultimate path to recognition will be expected from Serbia.”62 Kukleci broadly agrees, and says Osmani and Kurti have both hinted that “Pristina made too many concessions and Belgrade too few.”23

Despite differences among Kosovo’s political parties, most Kosovars want a comprehensive agreement with Serbia, with recognition of Kosovo’s sovereignty the ultimate goal.22 Where Kosovars sometimes differ is the issue of territorial integrity. Some Kosovars, especially LVV’s leaders, are determined that the territorial integrity of Kosovo should be upheld,18 while others are open to some form of “border correction” that would help Kosovo attain its main goal.40 Given the outcome of the 2021 parliamentary election, the camp opposing land swaps and an ASM with strong executive powers will have the upper hand.

Kosovo’s minister of justice, Selim Selimi, says many Kosovars also want to see some form of transitional justice for heinous crimes committed during the Kosovo war.22 Some stakeholders have even proposed amnesty for war crimes and crimes against humanity in order to smooth relations between Serbia and Kosovo.63 However, it is unlikely that LVV will support an agreement if it provides blanket amnesty to Serbia.64

In sum, the fractured nature of Kosovo’s political landscape has made reaching a comprehensive deal hard to achieve. Following the 2021 parliamentary election, LVV will dominate Kosovo politics, which could bring greater stability to the negotiations. Still, given LVV’s view that Kosovo’s past negotiators already conceded too much, it is unlikely that a deal acceptable to Vučić — involving land swaps, an ASM with formidable executive powers, or blanket amnesty — will be reached.

3.2.2 Influencers

The Serbia-Kosovo dynamics are strongly shaped by Russia and, more recently, China. The U.S. and EU are also important influencers, but they have different goals for the region from Russia and China and are better understood as mediators. The key question is, what are Russia and China’s goals and how will their pursuit of those goals affect the Serbia-Kosovo normalization process?

3.2.2.1 Russia

Ben Hodges, the former U.S. Army commander in Europe, called the Kremlin “the number one obstacle to ever getting any resolution” to the Serbia-Kosovo dispute.38 According to a Western diplomat, Russia is “vehemently opposed to Kosovo’s independence” and continues to threaten to use its veto power in the UN Security Council to block recognition.24 Russia’s traditional relationship with Serbia runs “deep” and it is “unmatched” compared with any other state.36

A primary objective for Russia is to keep the region divided to prevent the Balkans from integrating into the EU and NATO, and from adopting Western-style democracy.65 At the same time, Russia has strategic economic interests in the Western Balkans, especially in Serbia. Naftna Industrija Srbije, Serbia’s oil and gas monopoly, is majority-owned by Gazprom — the world’s largest publicly listed natural gas company, and Russia’s largest company in terms of revenue. Recently, Russia also made significant progress in the construction of Gazprom’s TurkStream II pipeline, which will branch off of the newly opened TurkStream gas line between Turkey and Russia to bring gas to Bulgaria, Serbia, and eventually Hungary, solidifying Russia’s energy hegemony in the CEE region.66 For Russia, “energy is everything,” said Ivana Stradner of the American Enterprise Institute.67 Full integration of Serbia into the EU would strike a huge blow to Russia’s oil and gas monopolies in the region.

Bugajski said President Vladimir “Putin is not a chess player … his sport is judo. He throws his larger opponent to the ground” by using “pressure points” such as kompromat, energy dependency, funding strategic political parties, cyberattacks, and propaganda.68 In the Western Balkans, propaganda is particularly important. According to Balkans expert Dimitar Bechev, the Kremlin is less willing to interfere militarily in the Western Balkans than in states that were part of the Soviet Union.69

It is often said that “the Balkans produce more history than they can consume.”70 Russia knows how to manipulate history to maintain divisions among Balkan identity groups. Sputnik Srbija and other propaganda outlets in Serbia tend to promote a wide assortment of narratives, ranging from “the EU is hegemonic” to “NATO is not beneficial.”71

Common Sputnik Srbija Narratives72

Importantly, Russia’s presence in the Balkans is a two-way street: The Kremlin wants to play a disruptive role, but there are also actors in the Balkans demanding an active Russian presence. In 2019, the culture ministries of Russia and Serbia released an action-packed, Hollywood-style film called Balkanska međa (Balkan Line).24 The film fictionalizes events at the close of the Kosovar war. Serbs are portrayed as the victims, Kosovars as savage perpetrators supported by NATO aggressors, while the Russians come in on the side of Serbs as their saviors. Although Balkanska međa presents the events as true, the film is packed with colorful disinformation.73

These narratives help to keep alive and forge anti-Western animosities in the region and undermine the EU and U.S.’s image as credible mediators. Even when Russia’s propaganda does not attack the dialogue, it makes it hard to find a solution to the Serbia-Kosovo dispute, especially one where the U.S. or EU are expected to play the role of honest brokers.

Russia is married to the UN Security Council’s Resolution 1244, which authorizes the UN to facilitate a political process to determine Kosovo’s future. Sergei Lavrov, Russia’s foreign minister, recently said Russia would accept only a deal that has been approved by Serbia and the Security Council.74 As for the EU, even if Russia allows Serbia to enter the supranational structure, some observers are concerned that it may become the Kremlin’s “Trojan horse.”40

3.2.2.2 China

Like Russia, China continues to side with Serbia, and it has the power to block Kosovo’s recognition by the UN Security Council. Furthermore, Serbia is one of the only countries in central and eastern Europe (CEE) that defends China on highly controversial political matters, especially human rights.75 Support for each other is a case of mutual back-scratching. China’s refusal to recognize Kosovo’s independence is not merely in solidarity with its Serbian ally, but also because it does not want to open up discussion about secession of Taiwan and Hong Kong.76

China is rapidly becoming a prominent player in the Balkans. The growing Chinese economy is roughly six times larger than the stagnating Russian one.77 Serbia is probably the most pro-China country in the Western Balkans, and from 2017 to 2019, it was the largest beneficiary of loans under the Belt and Road Initiative, with borrowing amounting to €5.5 billion.78 Those loans come with conditionalities and provide the creditor great leverage over the debtor.79

Serbia is among China’s top four trade partners in CEE. Chinese imports into Serbia have increased by 94 percent since 2012 and the country’s trade deficit with China tops $2 billion.80 At the same time, Serbia has gone from being a small recipient of Chinese foreign direct investment to the second largest in the Balkans.81 Chinese FDI could soon surpass that of Russia.36

The Serbian government is by far the biggest promoter of China in the Balkans. In the midst of the covid-19 crisis, China actively engaged in “mask diplomacy,” sending medical supplies to some European countries, including Serbia.82 In March 2020, Vučić stood in front of the world’s cameras and claimed that China is “the only one who can help Serbia” and that “European solidarity” is “just a fairy tale.”83 Chinese flags and symbols were rolled out all over Belgrade and other cities, even on government buildings, and a video of Vučić kissing the Chinese flag was reportedly viewed by more than 1.1 billion people.6 It reinforced the perception that the Chinese government is a much stronger and a more responsible partner than the EU, even though the EU provides significantly more aid to Serbia than any other partner (see figure below). Similarly, in January 2021, Vučić extolled China’s role in “saving” Serbia by providing covid-19 vaccinations to his nation while blaming the EU for the slow rollout of the COVAX program. That is a misrepresentation of the reality, as COVAX is managed by Gavi, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, and the World Health Organization.84

Part of the Chinese attraction can be explained by the fact that China plays by different rules than the U.S. and EU. While the EU, for example, has certain environmental standards when investing in some high-carbon industries, China has no qualms with it. More importantly, China will not call out Vučić’s increasingly autocratic regime. In turn, Serbia supports the One China Principle, which goes further than the One China Policy as it considers Taiwan an inalienable part of China.85 Serbia is also willing to defend the Chinese regime’s genocide against Uighurs.86 China’s relationship with Serbia is bound to have serious political consequences, especially for democracy, media freedom and other liberties.87 In Serbia, China helped to institute Huawei’s surveillance system of facial and license plate recognition and has held joint counterterrorism exercises with Serbian police.88

Some observers express concern that deeper cooperation of a dubious nature with China could, in the medium to long term, threaten Serbia’s prospects for EU integration.89 Serbia’s increasing economic cooperation with China may also eventually make EU membership less important. While China’s economic relationship with Serbia is less significant dollar-for-dollar than the Serbia-EU relationship, Vučić is also expanding the country’s relationship with Russia, the United Arab Emirates, and others, and he is pushing for greater integration of the Western Balkans and the Eurasian Economic Union. The overall effect is that actual EU membership becomes less important to Serbia and therefore less of an incentive for progress in the dialogue with Kosovo.90

3.2.3 Mediators

To a degree, the outcome of the conflict resolution process can be determined by the mediators, who can facilitate agreement by providing “ripening agents,” such as development aid, political support, security assurances, military assistance, instituting or lifting sanctions, and trade incentives.91 The two top mediators in the Serbia-Kosovo dispute are the EU and U.S.

3.2.3.1 EU: the Belgrade-Pristina Dialogue

Henry Kissinger is frequently but wrongly credited for asking, “Who do I call if I want to speak to Europe?”92 It is nonetheless an appropriate question, highlighting cleavages among EU countries that are particularly pronounced in the Serbia-Kosovo dialogue. While most EU members recognize Kosovo’s independence, there are five non-recognizing states that fall into two categories: “hard” non-recognition states — Spain and Cyprus — and “soft” non-recognition states — Greece, Romania, and Slovakia.32 Consequently, the EU talks about the “Belgrade-Pristina” rather than the “Serbia-Kosovo” dialogue, and it cannot fully leverage its economic power to facilitate the process.

The EU high representative for foreign affairs and security policy, Josep Borrell, and the EU special representative for the Belgrade-Pristina dialogue, Miroslav Lajčák, are from non-recognizing states, Spain, and Slovakia, respectively. As a result, some Kosovars doubt that the EU can mediate an end to the dispute.93

The Brussels dialogue initially kicked off in 2011 by focusing on technical issues, such as telecommunications, regional cooperation, and freedom of movement, before the EU escalated the talks to a political level.94 The hope was that agreement and implementation on technical issues would have a positive spillover effect into more political matters. Although the EU had initial success in producing 33 agreements between Serbia and Kosovo, many agreements were never implemented.

From November 2018 until recently, the EU dialogue was particularly deadlocked. Lajčák has injected new energy into the effort since his appointment in April 2020. In the midst of the covid-19 crisis, France and Germany hosted a virtual summit on July 10 between Vučić and Hoti, while the EU facilitated face-to-face discussions on July 16 between the two leaders. Those meetings marked the first EU-led dialogues in 18 months. Since then, Lajčák has conducted regular engagements between the Serbian and Kosovar leaders. He is pursuing a “comprehensive agreement” and “expects the sides to implement all agreements reached in the past.”95 As for unresolved issues, those are expected to be “resolved in parallel in the negotiations for a comprehensive agreement.”6

Some Balkan observers argue that one of the greatest carrots in the mediation process is eventual EU membership,31 which the bloc has conditioned upon normalization of relations between Serbia and Kosovo.96 Normalization, however, does not explicitly entail “recognition” of Kosovo by Serbia.97 Furthermore, although some member states, notably Germany, have spoken out against land swaps, Borrell said in May 2020, “I see no need for us to be more Catholic than the Pope.”98 In other words, it is not up to the EU to tell Serbs and Kosovars what they should agree on or not. Lajčák has nonetheless called a territorial exchange “extremely dangerous.”99

The importance of the EU in the Serbia-Kosovo dialogue lies in geography and potential economic leverage. That is, “Serbia [and Kosovo are] in Europe,” not in the U.S., as Stefan Vladisavljev has pointed out.36 In fact, the EU remains Serbia’s largest investor and trading partner.100 Nearly 70 percent of Serbia’s exports head to the EU market. Between 2009 and 2018, the value of Serbia’s exports to the EU more than tripled, from €3.2 billion to €10.9 billion. Furthermore, FDI from the EU amounted to €13 billion from 2010 to 2018, or 70 percent of Serbia’s total FDI.101 Overall, the economic relationship between Serbia and the EU is much more significant than Serbia’s relationship with China.90

Serbia further benefits from the EU’s Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance (IPA), which includes aid for transition and institution building, cross-border cooperation, regional development, human resources, and rural development.102 IPA II assistance from 2014 to 2020 amounted to €1.54 billion for programs for competitiveness and growth; environment, climate change and energy; transport; and agriculture and rural development.103

EU membership is also a high priority for Kosovo, according to Ambassador Mimoza Ahmetaj, head of the Kosovo mission to the Council of Europe and a former minister of EU integration. However, Kosovo is behind Serbia in the line for accession, given that the Serbian government initiated the Stabilization and Association Agreement with the EU around the same time Pristina declared independence.104 The EU and the U.K. are Kosovo’s largest export markets, absorbing 49.4 percent of its exports, and the largest import markets, sending 53.4 percent of imports.105 The EU’s IPA II assistance to Kosovo from 2014 to 2020 was €602.1 million.106 Still, Kosovo remains the only state in the Western Balkans that does not have an agreement on visa liberalization with the EU, even though it has met all the requirements since mid-2018.

In theory at least, the EU also gains in importance considering that the path toward EU membership should help to facilitate Serbia and Kosovo’s move toward democracy.36 The closer Serbia moves toward EU integration, the more political the requirements become, dealing with issues such as the rule of law, media freedom, and freedom of expression.33

In October 2019, France vetoed opening EU membership accession negotiations with Albania and North Macedonia. Since then, the EU has shied away from words such as “enlargement” and “accession.”100 As a result, Western Balkan officials and others worry that the prospect of EU membership is no longer realistic enough to get Serbia to commit to a comprehensive agreement.107108

3.2.3.2 U.S.: the Serbia-Kosovo Dialogue

Serbia is often called the most anti-American state in the Balkans, while Kosovo is called the most pro-American state, not only in the Balkans, but perhaps in the world.3 That changed a bit under Trump. While the U.S. was still popular in Kosovo, it would probably be more accurate to say that the U.S. briefly become less hated in Serbia. Vučić in particular was a fan of Trump’s and his special presidential envoy for the Serbia-Kosovo talks, Richard Grenell.109

On the Serbia-Kosovo dispute, Grenell’s appointment signaled a shift from the U.S. State Department toward the White House, and observers questioned whether Grenell aligned his efforts with Matthew Palmer, a career diplomat and the special envoy for the Western Balkans. The shift may have been precipitated by Trump’s general distrust of the State Department, but it probably also occurred because Grenell brought his own agenda to the table. The Serbia-Kosovo dialogue was allegedly a way for Trump to get a quick and easy foreign-policy win in advance of the 2020 U.S. presidential election.110 According to former senior State Department official Nicholas Burns, this was a departure from past U.S. administrations’ bipartisan approach to foreign policy, especially on Balkan issues.111

Since the turn of the century, U.S. foreign policy goals for the Balkans have been fairly consistent: EU and NATO accession and regional integration. Burns said those goals were largely derived from George H. W. Bush’s formulation in 1989 of “Europe whole and free.”6 Interlinked to Bush’s idea, Daniel Serwer argues that U.S. foreign policy goals for Serbia and Kosovo rested on three pillars:112

- Protection of Kosovo’s population and sympathy for Kosovo’s independence aspirations as well as a commitment to Bosnian sovereignty.

- Support for liberal democracy throughout the Balkans.

- A commitment to act in tandem with the Europeans, especially with Germany and the U.K.

During the last year of his presidency, Trump ventured away from the three foreign policy pillars.

First, although Trump initially highlighted the need for “mutual recognition,”113 his administration went weak-kneed on the goal of promoting Kosovo’s independence, undermining Kosovo’s sovereignty and aspirations by entertaining the idea of “land swaps.”114

Second, the Trump administration undercut stability and liberal democracy in the Balkans by freezing $50 million in economic aid for Kosovo and threatening to withdraw U.S. troops from Kosovo if Kurti’s government did not lift tariffs against Serbia, which had been levied following the Serbian government’s escalation of its de-recognition campaign.115 The Trump administration’s threats caused great concern in Kosovo and ultimately led to Kurti’s ouster. Kosovars depend heavily on the U.S. and the NATO-led peacekeeping force, Kosovo Force (KFOR), for security. As Ben Hodges notes, both Serbs and Kosovars will tell you in private, “Please don’t pull KFOR because it is the only anchor of stability in the region.”38

The Trump administration’s approach of putting pressure on Kosovo did not fit the reality of the situation. Serbia and Kosovo are “not at war” with each other, so there was “no need to rush” the process at that particular moment, said Kreshnik Ahmeti, the LVV official.53

Third, Grenell’s approach assumed a division of labor between the U.S. and EU, with the U.S. responsible for solving economic issues and the EU in charge of political normalization.

Burns said Grenell’s approach to separate U.S. and EU efforts was deeply flawed. “Most Americans of both parties who have been involved with the Balkans in the past 20 to 30 years understand that diplomacy works best when the U.S. and EU member states work together, when we are integrating our policies,” he said.111

The irony of Grenell’s economic normalization approach is that U.S. strength in the Balkans lies not so much in economic weight. For example, the U.S. is not among Serbia’s top five import or export partners.116 Not to mention that political issues and economic issues are intertwined in the Serbia-Kosovo context. “The issue of trade normalization is not solely about whether Kosovo can export its goods to Serbia without barriers to trade, but also about if labels reading ‘made in Republic of Kosovo’ will be on the packages,” said Austin Doehler, a visiting scholar at the Penn Biden Center.117 Besides, Grenell made no effort to coordinate the U.S. and EU dialogues.118

The Washington agreement brokered in September 2020 by the White House seemed aimed at scoring points ahead of the U.S. election rather than fulfilling long-standing U.S. foreign policy goals.119 It was also the epitome of Grenell’s flawed approach. In Kosovo, some referred to the agreement as “çorbë,” which translates to “mishmash.”120 A list of commitments rather than an international agreement, it did not deal with many economic issues, as Grenell had promised, and because of lack of coordination, the EU expressed concern that certain aspects of it could undermine Serbia and Kosovo’s future EU membership.121

Relations among the U.S., Serbia, and Kosovo may change in the coming months. Before the U.S. election, Vučić explicitly stated that Trump’s re-election would be better for U.S.-Serbia relations.122 Trump was perceived as an outsider, given that he was not in government when Biden advocated for NATO bombing of Serb targets in the 1990s in order to stop Milošević’s atrocities and genocide. At the time, Vučić supported the idea of Greater Serbia, and in 1999 as minister of information, he dubbed NATO’s actions “criminal” and characterized the military alliance as a “Neo-Nazi” organization.123

Nor was Trump in government, unlike Biden, when the U.S. recognized Kosovo’s independence. As vice president, Biden visited Serbia and encouraged Vučić to normalize relations with Kosovo. Biden’s long-term engagement with the Balkans explains why Vučić was unenthusiastic about the prospect of a Biden administration prior to the election, stating that Biden’s actions “did not bring much luck to Serbia in the past.”124 Vučić nonetheless congratulated Biden following his win and expressed a wish for greater cooperation with the U.S., leaving some room for strengthening U.S.-Serbia relations.125

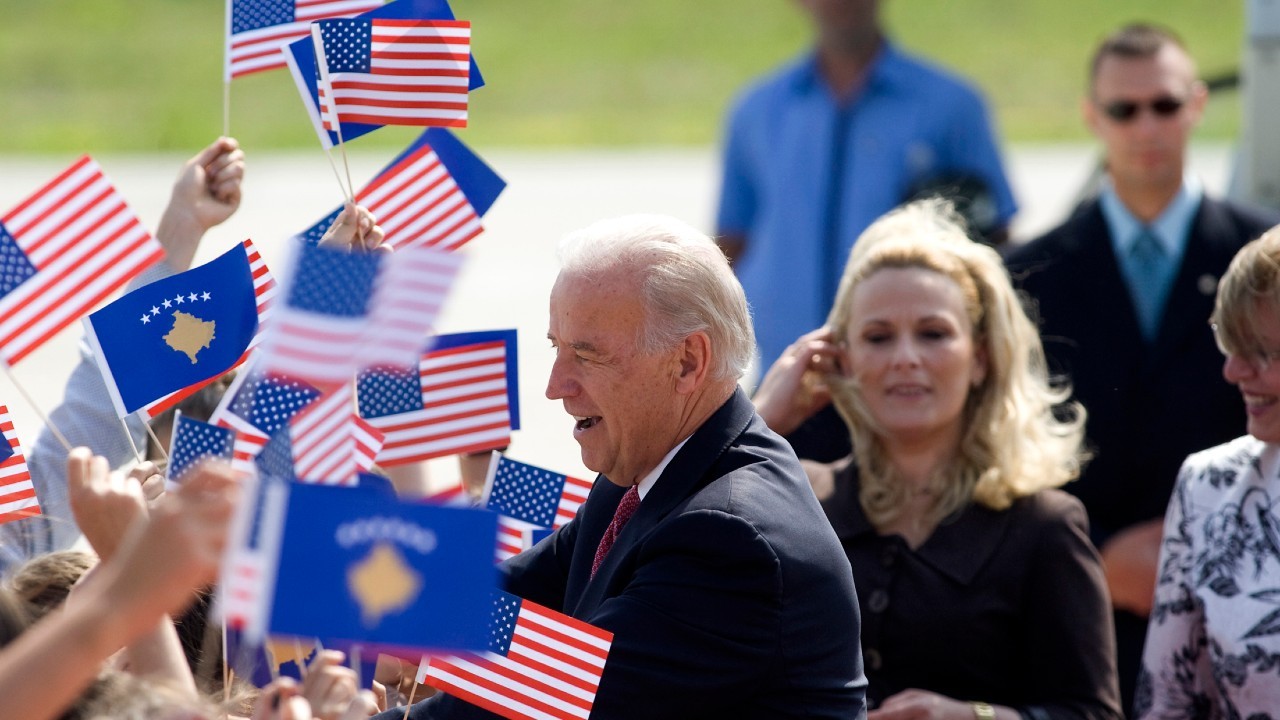

In Kosovo, Biden enjoys liberation credentials and he is deeply popular. His relationship with the region is also personal. Biden’s late son, Beau, even served the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) in Kosovo to develop the country’s judicial system. After Beau passed away, Kosovo named a 21-mile stretch of highway after him. Expectations will be high that Biden will continue to help Kosovo’s struggle to attain security and to gain international recognition.

Prior to the election, Kurti urged Albanians in the U.S. (from both Kosovo and Albania) to vote for Biden.126 Following the U.S. election, Osmani and several other Kosovo politicians also expressed optimism about the Biden administration, which will have a lot of clout in bringing Kosovars, including Kurti, back to the negotiation table.127

3.3 Context

It is difficult to identify contextual issues and to see, in the moment, if they will help or hinder resolution of the conflict.128 Yet two issues will be explored in relation to the Serbia-Kosovo dialogue: the lack of a “hurting stalemate” and the covid-19 crisis.

The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute uses the term “dispute” rather than “conflict” for situations, like Kosovo’s and Serbia’s, that claim fewer than 1,000 casualties per year.129 This is an important point. While it does not follow that the Serbia-Kosovo dispute should remain unresolved — disputes can escalate into conflicts, and Balkan conflict situations tend to spill over — there is no “hurting stalemate,” in which the costs of continuing the dispute exceed the benefits of ending it.130 The absence of a costly, violent conflict means that neither Serbia nor Kosovo has a sense of urgency to immediately end the dispute.

Given the mammoth global consequences of covid-19, this research paper also considered the possible effects of the pandemic on the negotiations. As the pandemic is fluid, a lot can still happen in the coming months, but we can make some initial observations.

In Serbia, the covid-19 crisis largely strengthened Vučić’s hand. In the first few months, he exploited it to monopolize the media and then eased covid-19 restrictions briefly to facilitate elections while the iron was hot. Then Serbia experienced mass protests, some of which were related to Vučić’s covid-19 measures.131 In a dramatic turn of events, by the beginning of February 2021, Serbia, with strong support from China, boasted that it had the second-fasted vaccine rollout in Europe.132

Given LVV’s strong support during the February 2021 election, expectations are high that Kurti should effectively deal with the pandemic and accompanying challenges. Over the past few months, covid-19 cases have started to surge in Kosovo, which could have major implications for health care, the economy, and political stability.133 Although covid-19 did not directly lead to the collapse of Kurti’s 2020 government, it was used as an excuse to unseat him in Kosovo.134

Some observers noted that the covid-19 crisis forced Western Balkan countries, including Serbia and Kosovo, to cooperate with one another. The two countries were even praised for sending medical aid and health workers back and forth and for coordinating border inspections.135 But a closer look shows that cooperation was largely along ethnic lines. Serbia sent aid to northern Kosovo to areas inhabited by Kosovo Serbs, while Kosovo sent aid to non-Serb areas in Serbia. There was no reciprocity across ethnic lines, which hindered the trust-building needed to facilitate an agreement. In a provocative move, Vučić even sent vaccines to Serb-majority municipalities in Kosovo.136

Overall, covid-19 stings, but so far it has not hit hard enough to force the adversaries to negotiate a comprehensive agreement that would lead to full normalization of relations. Serbia’s economy shrunk by approximately 3 percent in 2020, and by mid-February 2021, the country had had nearly 4,500 covid-19 deaths.137 By comparison, Kosovo’s economy declined by 8.8 percent in 2020 and, with a population about one-quarter that of Serbia’s, it experienced about 1,500 deaths by mid-February 2021.138 Kosovo’s economic hardships may be offset by remittances from the diaspora.

3.4 Serbia and Kosovo’s Strategies to Achieve Their Goals

The two adversaries can choose from a variety of strategies, from war to bilateral negotiations, to achieve their goals. At this point, neither is likely to revert to war, but it is not impossible for a frozen conflict to reignite at some point.139 That said, what would be Serbia’s and Kosovo’s “best alternative to a negotiated agreement” (or BATNA)?140 Put differently, what alternatives do the adversaries have to achieve their goals should they reject a comprehensive agreement?

For Serbia, Vučić’s public positions are that he wants to normalize relations with Kosovo and to get Serbia into the EU. However sincere he is or is not about ending the dispute, just by engaging in the dialogues Vučić has softened his image among international players while extracting major benefits from the EU and, to a smaller extent, from the U.S.

Goals are even more important than public positions. When asked what Vučić essentially wants to achieve, many interviewees answered that he sees himself as a historic figure. He wants to deliver economic prosperity for Serbia and to stay in power. To do that, Vučić does not need a comprehensive agreement that would lead to recognition of Kosovo, even if it means his country will not be joining the EU. Rather, the EU is merely a means to an end.

Visar Xhambazi counts Serbia among the Balkans’ “stabilitocracies,”141 defined as “governments that claim to secure stability, pretend to espouse EU integration and rely on informal, clientelist structures, control of the media, and the regular production of crises to undermine democracy and the rule of law.”142 Politically, it does not make sense for Serbia to become a full-fledged EU member, because the closer the country comes to entering the supranational structure, the harder some member states will push Belgrade to get serious about accountability, democracy, and the rule of law. And the EU’s bad experience with Hungary and Poland has taught it a lesson. “The EU won’t let Serbia join the body without solving those political issues,” one European ambassador said.143

In this context, Vladisavljev said, “Serbia is satisfied with the current status.”36 One Western diplomat similarly said it is questionable whether Vučić truly wants Serbia to become an EU member.24 Serbia has already reaped a range of pre-accession benefits, from greater investment confidence to better access to EU markets. What would be rational for Serbia as a whole (that is, EU integration), may not be rational for Serbian elites, who would like to remain free of strict EU regulations on environmental issues, transparency, and tendering. Being associated with the EU without actual membership allows Serbian elites to continue to benefit from Chinese, Russian and other investment with little or no regard to those concerns.25 To be clear, EU membership and economic cooperation with Russia and China are not mutually exclusive (except where sanctions against Russia come into play), but joining the EU will make it harder for Vučić and his cronies to engage in dubious business practices.

Vučić would suffer politically if he did not say the EU is still a priority for Serbia, even as he starts to publicly question the merits and credibility of the EU while exaggerating the benefits that Serbia accrues from China and Russia.144 Vučić is also promoting a common market in the Western Balkans, which could increase the region’s GDP by 6.7 percent.145 The combined effect is a stronger BATNA for Serbia as full EU membership comes to seem less necessary. Once EU integration is no longer the main carrot that drives the normalization process, recognition of Kosovo also becomes less important.

As mentioned earlier, Kosovo’s position is that it wants a comprehensive agreement with Serbia only if it entails recognition. Unlike Serbia, its public position is indistinguishable from its real goal: It wants sovereignty — in a manner that it is recognized by the UN and EU — and security. For most parties, transitional justice also remains a key goal, not merely a position.

In stark contrast to Serbia, Kosovo has a weak BATNA. In the absence of a comprehensive agreement, there are only a few options available to Kosovo’s government to partially satisfy its goals.

Kosovo will continue to bank largely on the mediation processes to promote international recognition of its sovereignty. “There is no alternative to the EU dialogue,” said Selim Selimi, Kosovo’s minister of justice.146 He also expressed a strong desire to have the U.S. at the negotiation table. Although LVV’s leaders had misgivings about the role of the Trump administration in the mediation process between Serbia and Kosovo, their tone following Biden’s win suggests that they would also like the U.S. to play a more constructive and active role in the dialogue.

If a deal cannot be reached through mediation, Kosovo could again revert to imposing tariffs on Serbia, especially if Serbia restarts its de-recognition campaign. Kosovo will also again seek recognition from individual states, as it has been doing since 2008 until the Washington agreement put a temporary stop to it.

Furthermore, Kosovo will continue to beef up its security sector, building a military that can make it less vulnerable to a Serbian takeover. In December 2018, Kosovo started the transformation of the Kosovo Security Force (KSF) from a lightly armed security and civil defense force into a professional army. Serbia strongly opposes the KSF’s transformation. The KSF expects to build a standing army of 5,000 troops and 3,000 reserves over the next decade. Still, Serbia’s military budget (€590 million) is more than 10 times that of Kosovo’s (€53 million).147

As for transitional justice, under current conditions, it will remain limited. Kosovo will merely be able to continue its own work on the issue.148 A transitional justice approach without Serbia’s participation is unlikely to facilitate normalization of the two entities.

4. KEY FINDINGS

After assessing issues, players, the context of the Serbia-Kosovo dispute, and the strategies of the adversaries, the main finding of this research paper is that the dispute is not ripe for resolution for the following reasons:

- The two most fundamental issues in dispute — sovereignty and security — are hard to resolve. More importantly, the adversaries are not ready to end the dispute, at least not under current conditions and in a manner that will soon produce a comprehensive agreement.

- Even though Vučić has the political power to make a deal with Kosovo, he and the Serbian public are dead set against recognition of Kosovo. He is also not preparing his public to make major concessions as part of the negotiation process.

- Kosovars agree that the basis of normalization should be recognition, but it is unlikely that an LVV-led government will agree to territorial exchanges, blanket amnesty, or an Association of Serb Municipalities with strong executive powers.

- EU integration, long an important incentive for normalization, is starting to lose its luster for Serbian elites. Vučić wants to have a courtship with the EU and all of the benefits that come with it, but he is unwilling to put a ring on her finger. Given the outcome of the 2020 parliamentary election in Serbia, Vučić’s true goals will increasingly crystalize. “Vučić cannot hide behind the parliament anymore — the next few months will show who he is” as he now has the power to do almost whatever he wants, one European ambassador said.143

- The main influencers, Russia and China, are both undermining the normalization process. Russia is set on protecting its energy interests in Serbia and on keeping the Western Balkans out of the EU and NATO. It therefore actively promotes anti-EU, anti-US, and anti-Kosovo propaganda that undermines a possible deal.

- China is not necessarily intentionally undermining the normalization process, but the relationship that it is developing with the Serbian government could compromise Serbia’s ability to integrate into the EU, which in turn makes EU integration a less powerful incentive for normalizing relations with Kosovo.

- Divisions within the EU mean that the dialogue lacks a clear, explicit goal — sovereignty for Kosovo — which weakens the process.

- Grenell’s insistence on splitting the dialogues into one led by the U.S. on economic matters and another led by the EU on political issues undermined the chances of reaching a comprehensive agreement. A package deal jointly coordinated with the EU stands a much greater chance of succeeding than Grenell’s fractionating approach.149

- In terms of contextual factors, there is currently no “hurting stalemate.” Although covid-19 could worsen the economies in Serbia and Kosovo, it has not yet produced enough pain to prod the parties to negotiate a comprehensive agreement.

- As for strategy, Serbia has a strong BATNA while Kosovo has a weak one, which means Kosovo needs the dialogue more than Serbia. Further EU integration (without actual membership) for Serbia, together with the strengthening of relations with China, Russia, and the benefits that will come with a common market in the Western Balkans, all bolsters Vučić’s hand even further.

5. POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

During the last year of the Trump administration, the U.S. did more harm than good in the Serbia-Kosovo dispute. The Trump administration disproportionately focused on securing a short-term political victory at the expense of finding a comprehensive solution to the Serbia-Kosovo dialogue. It risked not only undoing U.S. leadership and success in the Balkans, but also stifling the relationship between the U.S. and the EU. The Biden administration has an opportunity to do things right from the start.

There is no need to rush the Serbia-Kosovo dialogue, as the situation is not at a critical point. Rather, the mediation process should first be decelerated to allow for mainstreaming U.S.-EU coordination as well as to help prepare the parties, especially Kosovo, for upcoming negotiations.

For negotiation purposes, Serbia is stable and “monolithic” while Kosovo, because of major political changes, has been unstable and “heterogeneous.”150 The February 2021 election results may bring more stability to Kosovo, but LVV may still need support from other parties to forge consensus on an agreement. And the LVV-led government will be preoccupied with its domestic agenda before it can give any energy to the dialogue. The U.S. should advocate for slowing down the current pace of the mediation process so that the incoming Kosovo government can get its house in order and form a one-team approach — an internal agreement on a basic framework among Kosovo’s leading parties before they go back to the negotiation table.

The U.S. and EU should invest more in fighting disinformation in the Balkans and should call out Vučić for allowing narratives against Kosovo, the U.S., EU, and NATO to fester. Demonization makes agreement and implementation exceptionally difficult, and it should be replaced by positive, trust-building messaging.

Finally, the mediators need to recognize that a comprehensive agreement between Serbia and Kosovo may not be forthcoming in the short to medium term, which means the U.S. should return to playing the long game in the Balkans. That would require maintaining the special envoy for the Western Balkans position created during the Trump administration and, more importantly, once again taking a bipartisan approach that would mark a return to the three main pillars of U.S. foreign policy on the Serbia-Kosovo dispute: protecting Kosovo’s independence, supporting liberal democracy in the Balkans and acting in tandem with the EU and U.K.

Photo: Ethnic Albanian children wave U.S. and Kosovo flags as they welcome U.S. Vice President Joe Biden in Pristina Airport May 21, 2009. Biden received a tumultuous welcome upon his arrival to Kosovo on Thursday just hours after leaving Serbia where thousands of police kept streets empty to avoid protests. Credit: REUTERS/Hazir Reka

5. 1 Protecting Kosovo’s independence

The U.S. must make preservation of Kosovo’s sovereignty the top goal. The Trump administration’s threats to pull troops from Kosovo unless it dropped tariffs, rather than punishing Serbia for its de-recognition campaign, was misplaced. It appeased the perpetrator rather than helping the victim, even though preservation of Kosovo’s territorial integrity has been a bipartisan issue for successive U.S. administrations. The problem with appeasement is, to paraphrase negotiations expert William Ury, if you keep on throwing steaks to a tiger, the tiger will not become a vegetarian.”151

The protection of Kosovo’s independence also entails preservation of the country’s existing territorial integrity. The U.S. needs not only to continue to disavow the idea of a land swap, but also to clarify that the idea is, as Balkans expert Gorana Grgić put it, “dangerous” and “disconnected from the historical and regional contexts.”3 Territorial exchanges along ethnic lines will have regional implications and “Bosnia is put second in line on the chopping block … it is a recipe for another war,” said Muhamed Sacirbey, Bosnia and Herzegovina’s foreign minister during the Bosnian war and a chief negotiator during the Dayton peace process.152

The idea of territorial exchanges breathes life into Milošević’s idea of a Greater Serbia, and an ethnically homogenous state is anathema to the EU’s and even NATO’s diversity. EU integration comes as a package — member states sign up to a set of economic and political practices.3 If integration — into the EU, NATO, or both — is a strategic goal for Serbia and Kosovo, they should not be discussing land swaps. Rather, they should focus on promoting and protecting minority rights.

Support for minorities will involve more than developing and protecting political rights. It may also involve a large economic commitment, at least initially, from the U.S. and EU. According to a Kosovo Serb activist, Serbia provides over €300 million in salaries, pensions, and a wide range of social programs for Kosovo Serbs each year — money that Kosovo does not have.19 Another study puts that figure at closer to half a billion euros annually.153 Kosovo’s government budget in 2019 was €2.37 billion.154 Removing the €300 million to €500 million burden from Serbia’s budget may be the “win” that Vučić is looking for.

5.2 Supporting liberal democracy in the Balkans

Vučić’s move toward authoritarianism is concerning, and he should not be rewarded by the U.S. and EU for bad behavior. In warning Serbian officials against trying to align their country with often-conflicting Western and Russian interests, a top U.S. diplomat quoted an old Serbian proverb back to them during a 2017 visit: “You cannot sit on two chairs at the same time.”155

With China’s fast-growing influence, Serbia is starting to sit on three chairs rather than two. The Biden administration should call it out. This year marks 140 years since the establishment of diplomatic relations between Serbia and the U.S. There is room to grow those relations, but those discussions should coincide with greater support for programs promoting liberal democracy, media freedom, human rights, and good governance.

The new U.S. administration should also back liberal democracy in Kosovo rather than undermining it, as its predecessor did. Like Serbia, Kosovo still needs serious support with its democratization project.156

5.3 Acting in tandem with the EU and the U.K.

Another lesson from ending the Yugoslav wars in the 1990s is that the U.S. needs allies in order to end the Serbia-Kosovo dispute, especially as the U.S. does not have nearly as much economic clout as the EU in the Balkan region.3

Given the historic baggage with Kosovo, Vučić will only accept an agreement that can be presented to Serbia as a “win.”36 The U.S. alone, especially the way Grenell operated, cannot offer an acceptable package deal that would lend itself to “logrolling,” whereby losses in one area can be offset by gains in others.157 U.S. and EU ripening agents will work only if they are collectively employed and geared toward the same goal.

The prospect of stronger EU economic cooperation remains attractive to both Kosovo and Serbia (even though Vučić may be ambivalent about actual EU membership). At the same time, the EU is less able to dangle membership as a carrot due to a perception that it is not serious about further enlargement.158 But even if EU membership is not a reality, the road toward EU integration is still valuable and the benefits of it should not be underestimated. The key would be to channel the EU’s leverage into transformative power to facilitate liberal democracy in the Western Balkans.

The U.S., U.K., and EU member states that recognize Kosovo’s sovereignty should encourage non-recognizing EU countries, starting with “soft” ones (Greece, Slovakia, and Romania), to follow suit. Recognition of Kosovo by more, or even better, all EU member states, could help to add pressure on Serbia to move the process forward.159 One role of a mediator should be to provide political cover to the parties, which is what a transatlantic alliance can do. More importantly, recognition of Kosovo by all EU countries would help to facilitate the greater cohesion needed to support a transatlantic dialogue. Mediation with clear goals stands a much greater chance of succeeding in the long run. “There is need for clearer goals about the dialogue,” said David L. Phillips, director of the program on peace-building and human rights at Columbia University. “We haven’t defined what normalization means,” he said. “Normalization should mean sovereignty for Kosovo and recognition of its independence by Serbia within Kosovo’s current borders.”28

Mediators should consider the current inequities in their dealings with Kosovo and Serbia. Kosovo needs much greater support to be prepared for EU and NATO integration, which would more adequately guarantee Kosovo’s sovereignty and security, the two fundamental issues of the Serbia-Kosovo dispute. As mentioned earlier, Kosovo still reaps fewer benefits from the EU than Serbia does. Furthermore, Serbia joined NATO’s Partnership for Peace (PfP) in 2006 and has developed a growing relationship with the alliance, even though it is closely allied to Russia and does not aspire to become a NATO member.160 Importantly, Kosovo’s participation in NATO’s PfP should be a priority.161 The December 31, 2020, invitation by the Iowa National Guard to the Kosovo Security Force to partner on international peacekeeping missions is a good start to fostering stronger U.S.-Kosovo cooperation.

- Amy MacKinnon and Robbie Gramer, “Vucic: Most Serbs Prefer a ‘Frozen Conflict’ with Kosovo.” Foreign Policy Magazine. 4 March 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/03/04/serbian-president-aleksandar-vucic-interview-frozen-conflict-kosovo/ [↩]

- Janusz Bugajski, CEPA lecture on Challenges to Security, Democracy, and Development, 12 May 2020. [↩]

- Gorana Grgić, Interview with author, 14 May 2020. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Various interviews with U.S. diplomats and European officials. [↩]

- Zartman, “‘Ripeness’: the importance of timing in negotiation and conflict resolution”, 20 December 2008, https://www.e-ir.info/2008/12/20/ripeness-the-importance-of-timing-in-negotiation-and-conflict-resolution/ [↩]

- Ibid. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Laura Silber and Allan Little, Yugoslavia: Death of a Nation (London: Penguin Books, 1997), p.37. [↩]

- David, L. Phillips, Liberating Kosovo: Coercive Diplomacy and U.S. Intervention (Cambridge: Center for Science and International Affairs, 2012), p. 10. [↩]

- John A Powell, the director of the Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society at the University of California, Berkeley, says “Othering … is based on the conscious or unconscious assumption that a certain identified group poses a threat to the favored group.” John A. Powell, Us vs them: the sinister techniques of ‘Othering’ – and how to avoid them, The Guardian, 8 November 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/inequality/2017/nov/08/us-vs-them-the-sinister-techniques-of-othering-and-how-to-avoid-them [↩]

- Ambassador Hajdin Abazi, Interview with author, 20 August 2020. [↩]

- David, L. Phillips, Liberating Kosovo: Coercive Diplomacy and U.S. Intervention (Cambridge: Center for Science and International Affairs, 2012), p. xv. [↩]

- Mose Apelblat, “Belgrade-Pristina dialogue resumed but normalization still far away,” The Brussels Times, 9 September 2020, https://www.brusselstimes.com/news/eu-affairs/130507/belgrade-pristina-dialogue-resumed-but-normalisation-still-far-away/ [↩]

- Robbie Gramer, “U.S. Plans to Jump Back Into the Balkans With New Envoy,” Foreign Policy Magazine, 30 August, https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/08/30/us-plans-to-jump-back-into-balkans-with-new-envoy-serbia-kosovo-dialogue-dispute-state-department-diplomacy-europe/ [↩]

- On background discussion with high-level EU official. 28 October 2020. [↩]

- David L. Phillips, “Trump Betrays Kosova,” Illyria, 4 May 2020, http://illyriapress.com/trump-betrays-kosova/ [↩]

- Leon Hartwell, The Mediation Dilemma and the Utility of Mediation in Conflict Resolution: A Case Study Approach, (University of Leipzig: Leipzig, 2019), pp 46-86. [↩]

- David, L. Phillips, Liberating Kosovo: Coercive Diplomacy and U.S. Intervention (Cambridge: Center for Science and International Affairs, 2012). [↩]

- Glauk Konjufca, Interview with author, 19 June 2020. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Kosovo Serb activist, Interview with author, 13 July 2020. [↩] [↩] [↩]