Executive Summary

- Fifth-generation networks (5G) need to be secured because they are going to be the backbone of the future digital economy.

- Security concerns over Chinese telecommunication companies have been raised because they are legally required to provide information to Chinese intelligence services.

- Future military solutions will potentially be based on commercial 5G solutions and proactive cooperation among NATO allies to protect essential networks from the influence of undemocratic countries is essential.

- Legal frameworks for the elimination of untrustworthy suppliers are currently being introduced in the Baltics, leaving no room for doubt that any Chinese technologies will be tolerated in their 5G networks.

- The Baltic states could be valuable partners in the development of secure 5G technology and networks.

- The U.S. Transatlantic Telecommunications Security Act should be approved to fund 5G infrastructure deployment in Central and Eastern Europe and to support the Three Seas Initiative as a potential alternative for the 17+1 (now 16+1) format.

Introduction

In the transition from 4G to 5G mobile networks, the West has a limited window of opportunity to lay sound foundations for the security of its data transfer infrastructure and the future it will underpin. The U.S.-led Clean Network initiative to secure 5G networks, the latest generation of data transfer technology, has encouraged like-minded countries to take the vulnerabilities of this technology seriously, with most even moving to eliminate untrustworthy suppliers from the process of building 5G infrastructure. Even though most of these countries have identified 5G rollout as a matter of national security, cybersecurity solutions are still only in their infancy. There is little time for their incubation before 5G infrastructure is fully established or malignant actors take advantage of its vulnerabilities. Greater cooperation among NATO members can potentially buy the West some time and speed up development in the area of policy and technology, spread the use of best practices, increase cohesion between the disparate efforts of allies, and create competitive alternatives to the products and services offered by Chinese suppliers. With this long list of tasks and the West’s economy, civil services, and military proficiency at stake, it is critical that we investigate what each ally has to offer.

This paper focuses on a particular set of allies, the Baltic states, and what can be gained from their experience as well as their resources. In the United States, lawmakers on May 19 reintroduced the Transatlantic Telecommunications Security Act, a legislation that provides essential financial support to Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries for the development of 5G infrastructure, that is economically viable, socially sustainable, and compliant with international law. The utility of this decision has been called into question — why pour financial aid into developed countries such as Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia? While it may seem that such support would generate value only for the beneficiaries, there is much to be gained in return, as the Baltic countries could be valuable partners in the development of secure 5G technology and networks in cooperation with democratic countries and institutions.

5G and Security

The global lockdown caused by covid-19 pandemic forced most individuals to adapt quickly to a new way of living: working from home, using remote meeting platforms, and shopping online. Businesses that had already invested in digital solutions flourished because they were prepared to adjust to the “new normal.” However, fourth-generation networks (4G) had already reached capacity with regard to their data transfer speeds, and this problem was being addressed with the introduction of a new fifth-generation (5G) mobile network and broader spectrums targeted at satisfying market needs. A full-capacity 5G network should produce the following advantages:

- A tenfold decrease in transfer delays, expected not to exceed 1 millisecond.

- One hundred times faster download speeds, at a data rate of up to 10 Gbps.

- One hundred times greater network capacity, allowing more connected devices.1

These developments would allow us to use better autonomous vehicles, conduct remote surgery, create smart factories, and enable IoT (Internet of Things) capabilities. 5G is going to serve as the backbone for the future digital economy and empower technology such as artificial intelligence, machine learning, and extended reality. According to a PricewaterhouseCoopers report on the global economic impact of 5G, by the year 2030, the total impact of 5G on the world economy is expected to amount to more than $1.3 trillion, increasing the U.S. GDP by $484 billion and creating up to 4.8 million jobs in the United States alone.2

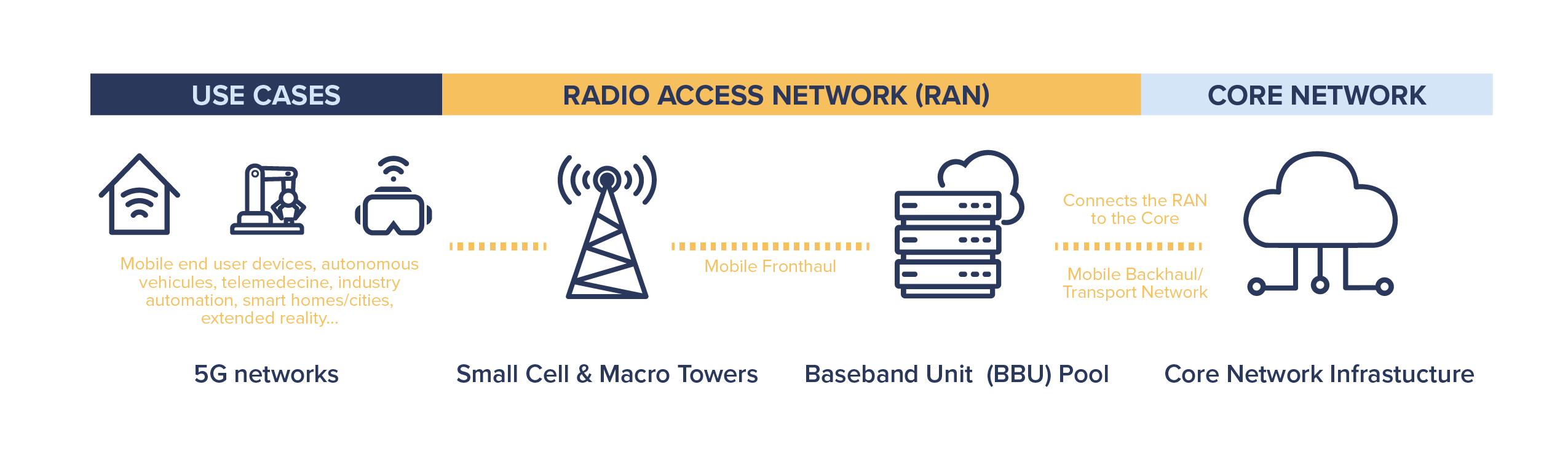

Figure 1. Example of 5G network architecture

Source: CISA (Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency), U.S. Department of Homeland Security. 2020. CISA 5G Strategy: Ensuring the Security and Resilience of 5G Infrastructure In Our Nation. Washington, DC: CISA, U.S. Department of Homeland Security. https://www.cisa.gov/sites/default/files/publications/cisa_5g_strategy_508.pdf.

5G brings with it a new technological landscape which entails a move toward more decentralized and software-defined networks as well as new capabilities such as virtualization. This inevitably leads to new security challenges. Numerous technical risks are addressed in the new security mechanics of 5G networks (new authentication procedures, privacy, and service-based architecture security, etc.).3

However, 5G security risks should not be addressed simply as a technical issue. The Prague Proposals, presented by government officials and security experts from the European Union (EU), NATO, and other countries in May of 2019, address the issues involved in ensuring a secure 5G rollout and identify that 5G security threats might also be caused by specific “political, economic or other behavior of malicious actors which seek to exploit our dependency on communication technologies.”4 In this context, privacy issues, such as location tracking, collecting user information and personal data, are not the biggest concern — rather it is the possibility of services and networks being disrupted or taken over that stands as the greatest threat with 5G networks. It is not difficult to imagine the damage that could be done to a smart city by disrupting its, say, autonomous transportation services or heating and water supply systems.

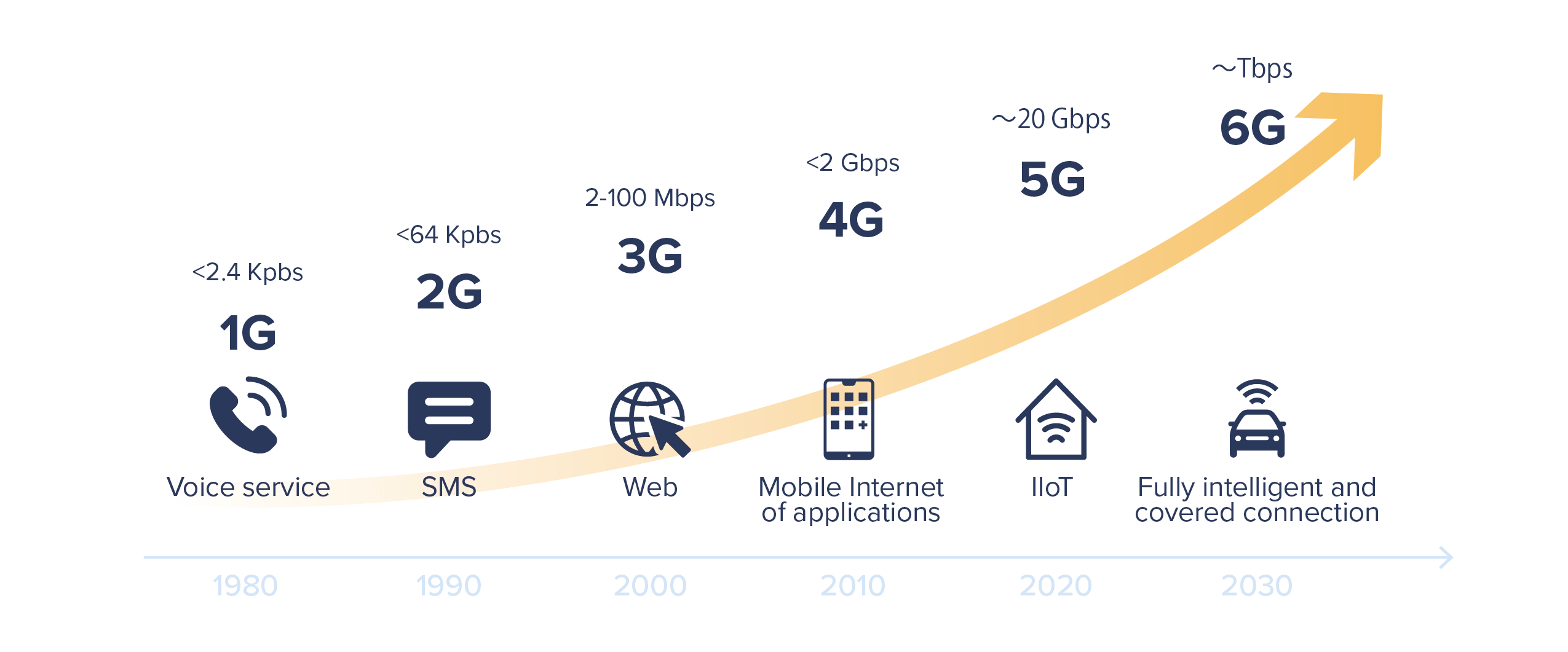

It is important to note that 5G must be viewed not as an endpoint in itself but as an important milestone in the further development of communications technology, with dependency on 5G-specific infrastructure set to last for at least a 10-year period and the rollout of new generation networks (6G) expected by 2030 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. The Evolution of Wireless Communication

With the abovementioned security issues in mind, in April of 2020, the U.S. Department of State introduced the Clean Path requirement for all 5G networks. The point of the Clean Path, as one of the expansion of Clean Network Initiative, was to eliminate all untrusted software and hardware suppliers. This led to the subsequent decision (made on June 30, 2020) of the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to formally identify two companies, Huawei Technologies Company (Huawei) and ZTE Corporation (ZTE), “as national security risks to America’s communications networks — and to our 5G future.”5 Both companies are obliged to cooperate with Chinese intelligence services as stipulated by China’s National Intelligence Law, which came into force in 2017, consolidating the legal power of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The law obliges all Chinese citizens and organizations to support the national intelligence services as requested without allowing for any possibility to refuse handing over data.6 Even though Huawei has on many occasions provided public reassurance that it does not install “back doors” into its systems and that it will never give up the data it has collected to the intelligence services, the greater concern is that there is no legal way for Huawei or any other Chinese company to refuse such a request from the Chinese intelligence services.7

By late 2020, at least 53 countries had joined the U.S.-led Clean Network initiative, which also was highlighted by the EU as having synergies with its own 5G cybersecurity toolbox, a set of measures adopted to guarantee the security of 5G within EU member states.8 Even though the 5G toolbox addresses the same security issues and specifies strategic tools to mitigate principal cybersecurity risks, it does not set out full unified and detailed regulation for countries within the EU. It simply suggests a general framework and points out where member states could take specific individual measures to protect their 5G networks.

Cooperation between EU member states in the field of security is still insignificant and so national security issues such as 5G security measures have to be resolved at the national level. Countries are under considerable pressure both from internal demand for services and the suppliers themselves to make commitments to specific suppliers and decide who they will be technologically dependent on for the foreseeable future. Because these decisions have to be made at the national level, this has turned individual member states into battlefields for technological influence.

Germany’s hesitation and continued discussions with Huawei about the company’s participation in its 5G rollout raised a lot of concerns, but eventually Germany issued legislation in May allowing the government to block “untrustworthy” suppliers.9 That same month, Italy approved Vodaphone’s decision to continue its cooperation with Huawei and its participation in the development of its 5G network.10

These events demonstrate that even though most EU countries have taken specific action to secure their 5G networks, we cannot expect to see a unified EU approach to Chinese telecommunication companies anytime soon and this may cause disunity within the EU. However, 5G should not only be considered a national security matter, it must be seen as a grave security issue for NATO. Future military solutions will potentially rely on commercial 5G solutions. The protection of essential networks from the influence of potential adversaries should be a critical strategic goal for NATO.

Lessons From the Baltics

Given the risks and opportunities associated with 5G, proactive cooperation among NATO allies is essential. Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, collectively known as the Baltic states, should be a good example to turn to because they have demonstrated a strong commitment to NATO defense, reacted with firm responses to risks identified as national threats, and have already taken specific steps with regard to 5G security.

As responsible NATO member states, all three countries are on a list of 11 (out of 29) countries that meet the commitment requirements of the North Atlantic Alliance to allocate at least 2% of national GDP to their defense budgets. In 2020, Estonia allocated 2.33% of its GDP, Latvia 2.27%, and Lithuania 2.13%. The Baltic states intend to either maintain this percentage or increase it. For example, Lithuania has included the strategic goal into its government program to reach 2.5% by 2030.11

Frequently, the most vocal critics of Russia within the EU and NATO, the Baltic states have considered Russia the main threat to their national security ever since they gained their independence in 1991. By 2019, all three countries came to recognize China as such a threat as well, approaching it with equally serious rhetoric and preventive measures.

In a 2019 report, International Security and Estonia 2019, the Estonian Foreign Intelligence Service identified China for the first time as a threat to national security, emphasizing China’s increasing investment in the technology sector as a means to reach its strategic goals. The report also confirms the existence of “back doors” on Chinese IT devices and the occurrence of cyber operations in the interest of the CCP and military, including instances of industrial espionage intended to give Chinese technology companies an advantage.12 Likewise, Latvia’s security service report of 2020 stated in no uncertain terms that China was involved in cyber espionage and that private and public entities with collaborative ties to China were the targets of Chinese cyber operations.13

In Lithuania, China was identified for the first time as a possible threat to national security in a 2019 report issued by the State Security Department. The report also highlighted that Chinese intelligence services had been expanding their operations in Lithuania.14 What is more, Lithuania was the first country to declare that it would not be participating in the 17+1 platform. The China-led initiative was formed in 2012 with the aim of promoting cooperation through investment in CEE infrastructure development. According to Lithuanian Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs Mantas Adomėnas, the format did not require official withdrawal and Lithuania has decided not to attend any future 16+1 events.15 The decision to decline participation was only made easier by the fact that the initiative failed to produce the investment hoped for. Lithuania has continued in its leadership role by encouraging other countries to leave the 16+1 format. Participation in the 16+1 initiative has divided EU members and currently presents difficulties for the EU as it formulates a unified approach to relations with China. According to Gabrielius Landsbergis, the Lithuanian minister of foreign affairs, “the EU is strongest when all 27 member states act together along with the EU institutions.”16

Security Through Policy

Growing concerns about the West’s increasing dependency on Chinese technology encouraged the Baltic states to take specific actions that would allow them to eliminate unreliable suppliers in order to protect national security interests. All three countries joined the U.S.-led Clean Network initiative by signing a joint declaration on 5G security (Estonia in October of 2019, Latvia in February of 2020, and Lithuania in September of 2020), highlighting 5G security issues and committing to start a “rigorous evaluation of providers and supply chains.”17 As was identified in the Prague Proposals, the first and most important pillar of guaranteeing the secure rollout of 5G networks is the establishment of a national policy for managing the influence of third-country suppliers.4 Legal frameworks for such policies are currently being introduced in the Baltics, leaving no room for doubt that any Chinese technologies will be tolerated in their 5G networks.

On May 12, 2020, the Estonian government approved the so-called Huawei Law which obliges organizations to apply for authorization when they wish to use communications network hardware and software in cases that affect national security.18 Specific criteria were introduced in a proposal for regulatory documents that led Huawei to declare that it would claim discrimination on the basis of origin.19 The government is introducing further amendments to the law in order to avoid such claims and create a complete legal framework for the elimination of untrustworthy suppliers.

Latvian regulation for the planning and implementation of security measures for critical IT infrastructure came into force in January of 2021. It stipulates that critical infrastructure demands the highest level of security and lays out requirements for hardware and software suppliers as well as beneficiaries to be registered in a NATO, EU, or European Economic Area (EEA) member state. Latvia has also acknowledged that ongoing 5G rollout processes may require additional measures and, therefore, does not rule out the possibility of making 5G security regulation even more stringent in the future.

In Lithuania, the commitment to eliminate untrusted software and hardware providers from 5G networks was included as one of the strategic aims of the new government program, approved in March of 2021.20 On May 25, 2021, the Lithuanian parliament clearly declared that Lithuania does not want to belong to the Chinese-controlled technosphere and introduced amendments to the existing legal framework that allow the government to prevent unreliable suppliers from participating in the electronic communications market. One of the main criteria in defining a trusted manufacturer is if it (or its beneficiary) is registered to a NATO country, the European Union, or the EEA and/or the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). This criterion is applied to the telecommunications company, equipment provider, and the equipment maintenance provider, which means that no so-called third-country companies can participate in the electronic communications market.

The Baltic states declare that 5G is just one aspect of the critical infrastructure that requires protection from unreliable equipment and third-country suppliers — the same legislation for assessing trustworthiness from the standpoint of national security should be applied to all critical and government infrastructure. The pressures of 5G rollout have forced immediate action with regard to 5G networks, but there is a strong consensus that tougher security measures and uniform security requirements are necessary for all critical infrastructure. This is especially important as public services undergo greater digitization and become increasingly dependent on information and communications technology.

Security Through Technology Development

While policy is the first and most important pillar of a secure rollout and the further evolution of 5G, it is also important to get back to the development and availability of 5G as a technology. From the very beginnings of 5G, security concerns were focused not only on core infrastructure (or “brains”) as with 4G, but also on its radio access network (RAN; see Figure 1) because 5G RAN is becoming increasingly dependent on software that is enabled through certain cloud-based solutions.21 RAN is responsible for connecting individual wireless devices through radio connectivity and it is solely vendor proprietary equipment.

The lack of global competitiveness in the RAN market and the subsequent dependency on suppliers explains China’s hold on the 5G market. There are only five companies that offer complete RAN solutions — the two Chinese companies ZTE and Huawei, the Scandinavian companies Nokia and Ericsson and, finally, South Korea’s Samsung, a less significant market player.22 The elimination of both Chinese vendors from 5G supply chains leaves only three suppliers to satisfy market demand in the United States, most of Europe, and other countries following a similar agenda.

This limited array of options shifts the focus onto technological development and other possible alternatives to replace single-vendor RAN solutions. One of them, Open Radio Access Network (O-RAN) is making its way into the market. The idea behind this innovation is to create a multi-vendor solution by disaggregating software and hardware and basing it on open interfaces and protocols.23 This solution should create supply chain diversity by attracting smaller players to the market and reducing the cost of building and maintaining networks.

Even though O-RAN was labeled crucial “in addressing the China challenge” by former U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, it should only be seen as one of many possible directions for 5G technology development.24 More importantly, like-minded NATO countries should be coordinating their efforts in the area of 5G innovation in order to avoid duplicating research and development (R&D) results and drawing up overlapping “safe” equipment lists for critical infrastructure supply chains. After all, the technological rivalry with China will only intensify in the future.

Photo: Locked Shields 2021. Credit: NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence

Ongoing Projects and the Potential of the Baltic States

There are already a few 5G security and technology development projects being implemented in the Baltic states that may be valuable to NATO partners as they navigate their own paths toward 5G security.

Estonia is host to the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence (CCDCOE), which is leading at least two key research projects on 5G security, including the security of 5G networks for military mobility funded by the U.S. Department of Defense and the Estonian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.25 Another important project is focused on identifying secure methods for the use of private and commercial 5G networks by NATO forces.26

Latvia set a great example as one the first European countries to launch 5G for commercial use back in July of 2019.27 It also opened the first military 5G test site in Europe at the Ādaži military base in November of 2020.28 The project is led by the mobile operator Latvian Mobile Telephone (LMT) in cooperation with the National Armed Forces with the aim of creating a viable environment for developing and testing new 5G defense technologies. The environment was created to make use of the combined capabilities of Latvian businesses, research centers, and defense experts to develop new sensors, defense systems, and other 5G-based technologies for national and allied armed forces.29

Meanwhile, Lithuania, with its upcoming 5G rollout, has much to offer in the way of cybersecurity capabilities that could serve transatlantic cooperation needs. The Lithuanian National Cyber Security Center (NCSC) is going to play a major role in the equipment trust verification process, where one of the NCSC’s functions is to provide cybersecurity assessments on specific devices and applications based on the needs of the private and public sector. Having already gained some experience in the assessment of specific Chinese equipment, the NCSC could focus more on studying 5G equipment by conducting detailed technical analyses. Transatlantic information sharing is important for a more comprehensive understanding of possible supply chain vulnerabilities. It may also serve as the basis for the inevitable list of trusted equipment NATO will have to create for its 5G supply chains.

What is more, the new Regional Cyber Defense Center (RCDC) launched pilot activities this May in Lithuania. The aim of this bilateral U.S.-Lithuanian initiative is to create a platform for sharing best practices in the field of cybersecurity, creating a permanent cyber training facility, and conducting R&D across the region by working together with Ukraine and Georgia in countering cyber threats. The RCDC, which will be targeting operational and tactical activities, could potentially focus on 5G security and other critical infrastructure within the region, including infrastructure in vulnerable countries such as Ukraine and Georgia. This could be achieved by analyzing potential vulnerabilities and proposing recommendations for targeted security measures.

In the area of R&D, the RCDC could draw on the capabilities of local companies and research institutes. The resources the Baltic states have to offer include the Ericsson Estonia and its development center in Estonia; LMT and partners, who are already creating an environment for testing 5G military applications at the Ādaži military base; the Lithuanian electronics company group Teltonika IoT Group, which recently announced plans to invest €2.5 billion ($2.97 billion) and build a Lithuanian semiconductor factory by 2030; and the Lithuanian-based Baltic Institute of Advanced Technologies, which is developing wideband RF and mm-wave hardware components for 5G applications and is about to launch a project together with European partners to develop an artificial intelligence-enhanced 6G transmitter prototype.30

Policy Recommendations

There will never be a better time to take preventive action than during this transition from one technological generation to the next if we wish to avoid becoming dependent on objectionable technology. Strengthening the Baltic states’ technological independence should not only serve to secure NATO’s critical infrastructure, which is vital for military interoperability as the Alliance attempts to reduce China’s influence, but it should also accelerate the development of new technologies and global competitiveness in technological solutions. The following are a set of recommendations for transatlantic cooperation that could potentially bolster and catalyze efforts to build a more secure 5G future.

- Initiate bilateral agreements between the U.S. Department of Defense and the Lithuanian and Latvian defense ministries on R&D, testing, and the evaluation of 5G projects, modeling the successful case of the Estonian and U.S. R&D collaboration agreement in the field of cybersecurity.31 On the basis of such agreements, it would be possible to implement the following initiatives and projects:

- Set up a transatlantic information exchange and use 5G supply chain equipment analysis conducted by the NCSC.

- Expand the future activities field of the RCDC, focusing on 5G security projects, including information exchange on cyberattacks, training, and cooperation implementing R&D projects. This would allow the RCDC to draw on the capabilities of local research institutes, private and public companies, and scientists. The RCDC could also open up opportunities for Ukraine and/or the South Caucasus region, as potential NATO members, by facilitating their preparation for future 5G security standards.

- Encourage combined testing at 5G testing sites in the Baltic environment, which would involve inviting the Baltic states’ armies to visit one of five U.S. 5G testing sites and allowing them to conduct feasibility studies, and hosting the United States and other NATO allies at the Ādaži military base in Latvia.

- Encourage the United States to lend its support to the CEE countries as they secure their telecommunication networks by approving the bipartisan TTSA, which was reintroduced in Congress on May 19.32 The TTSA enables the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) to fund 5G infrastructure development and the replacement of “covered” infrastructure in CEE countries to ensure transatlantic security and resilience against malign actors. The TTSA includes highly important support to the Three Seas Initiative (3SI) and prioritizes the countries within 3SI and the projects available for 3SI Investment Fund (3SIIF) financing. 3SI brings together 12 EU member states, located between the Baltic, Adriatic and Black seas, in order to strengthen economic growth and interconnectivity within the region focusing on development of energy, transportation and digital infrastructure. 3SI cooperation is vital in countering the region’s dependency on Russian energy as well as China’s influence in the transport and digital sectors.33

3SI has great potential alternative to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and its component “Digital Silk Road” for digital connectivity led by China’s technologies, as well as reduce the importance of 16+1 considering the BRI platform for CEE countries is being used as China’s back door to Europe. The 3SIIF, launched in 2019 for the realization of these objectives, already has a value of about €1.2 billion (around $1.43 billion), including investments from nine member countries and private investors. Furthermore, it is expected to raise funds eventually up to €5 billion ($5.97 billion) and assumed to generate up to €100 billion ($119.4 billion) investments.34

The TTSA, first introduced in the U.S. Congress in December of 2020, was criticized because it was intended to provide financial support to developed countries (3SI includes Austria and the Baltic states, which are considered developed by the International Monetary Fund). However, according to the chairperson of the Supervisory Board of the 3SIIF, Beata Daszyńska-Muzyczka, 3SI countries face a €600 billion ($712 billion) infrastructure quality gap compared with Western Europe.35 The dependency in the energy sector inherited from the Soviet era is a great example of the geopolitical and financial costs needed to shift away from existing infrastructure (40% of the 3SIIF funds are assigned to projects in the energy sector, including the U.S. pledge to invest $1 billion for 3SI countries’ independence in the energy sector).36

Acknowledgements

This program is made possible by funding from the Baltic-American Freedom Foundation (BAFF). For more information about BAFF scholarships and programs, visit www.balticamericanfreedomfoundation.org.

The views expressed by the author are their own and do not represent the views of BAFF.

- “CISA 5G strategy”. U.S. Cybersecurity & infrastucture security agency. 2020. https://www.cisa.gov/sites/default/files/publications/cisa_5g_strategy_508.pdf. [↩]

- “The global economic impact of 5G”. PricewaterhouseCoopers. 2021. https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/tmt/5g/global-economic-impact-5g.pdf.; Enrique Duarte Melo, Antonio Varas, Heinz T. Bernold, and Xinchen Gu. “5G Promises Massive Job and GDP Growth in the US”. February 2, 2021. https://www.bcg.com/publications/2021/5g-economic-impact-united-states. [↩]

- Anand R. Prasad, Alf Zugenmaier, Adrian Escott and Mirko Cano Soveri. “3GPP 5G Security”. August 6, 2018. https://www.3gpp.org/news-events/1975-sec_5g. [↩]

- “The Prague Proposals. The Chairman Statement on cyber security of communication networks in a globally digitalized world”. Prague 5G Security Conference. May 3, 2019. https://nukib.cz/en/infoservis-en/conferences/prague-5g-security-conference-2019/. [↩] [↩]

- “FCC Designates Huawei and ZTE as National Security Threats”. Federal Communications Commission. June 30, 2020. https://www.fcc.gov/document/fcc-designates-huawei-and-zte-national-security-threats. [↩]

- Girard, Bonnie. “The Real Danger of China’s National Intelligence Law”. The Diplomat. February 23, 2019. https://thediplomat.com/2019/02/the-real-danger-of-chinas-national-intelligence-law/ [↩]

- Kharpal, Arjun. “Huawei says it would never hand data to China’s government. Experts say it wouldn’t have a choice”, CNBC. March 4, 2019. https://www.cnbc.com/2019/03/05/huawei-would-have-to-give-data-to-china-government-if-asked-experts.html. [↩]

- “Meeting between U.S. Under Secretary of State Krach and Commissioner Breton on Secure Telecommunications Infrastructure and Digital agenda”. European Commission. September 30, 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/commissioners/2019-2024/breton/announcements/meeting-between-us-under-secretary-state-krach-and-commissioner-breton-secure-telecommunications_en [↩]

- Cerulus, Laurens. “Germany falls in line with EU on Huawei”. Politico. April 23, 2021. https://www.politico.eu/article/germany-europe-huawei-5g-data-privacy-cybersecurity/. [↩]

- Pollina, Elvina & Fonte, Giuseppe. “Italy gives Vodafone 5G deal with Huawei conditional approval – sources”. Reuters, May 31, 2021. https://www.reuters.com/technology/italy-gives-vodafone-5g-deal-with-huawei-conditional-approval-sources-2021-05-31/. [↩]

- Program of the eighteen government of the Republic of Lithuania. December 11, 2020. https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/973c87403bc311eb8c97e01ffe050e1c. [↩]

- Lau, Stuart. “Lithuania pulls out of China’s ’17+1′ bloc in Eastern Europe”. Politico. May 21, 2021. https://www.politico.eu/article/lithuania-pulls-out-china-17-1-bloc-eastern-central-europe-foreign-minister-gabrielius-landsbergis/. ; “International security and Estonia”. Estonian foreign intelligence service. February 28, 2019. https://www.välisluureamet.ee/pdf/raport-2019-ENG-web.pdf [↩]

- “2019 annual report“. Constitution protection bureau of the Republic of Latvia. April 27, 2019. https://www.sab.gov.lv/files/Public_report_2019.pdf. [↩]

- “National threat assessment 2019“. State security department of the Republic of Lithuania and second investigation department under the Ministry of National Defence,.February 5, 2019.https://www.vsd.lt/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/2019-Gresmes-internetui-EN.pdf. [↩]

- Meeting with Viceminister of Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Lithuania, April 2021. [↩]

- Lau, Stuart. “Lithuania pulls out of China’s ’17+1′ bloc in Eastern Europe”.Politico, May 21, 2021. https://www.politico.eu/article/lithuania-pulls-out-china-17-1-bloc-eastern-central-europe-foreign-minister-gabrielius-landsbergis/. [↩]

- “United States–Estonia Joint Declaration on 5G Security”. U.S. Embassy in Estonia. November 1, 2019. https://ee.usembassy.gov/joint-declaration-on-5g/. ; “Joint Statement on United States-Latvia Joint Declaration on 5G Security”. U.S. department of State. February 27, 2020. https://2017-2021.state.gov/joint-statement-on-united-states-latvia-joint-declaration-on-5g-security/index.html.; “United States – Republic of Lithuania Memorandumn of Understanding on 5G security”. U.S. Department of State. September 17, 2020. https://2017-2021.state.gov/united-states-republic-of-lithuania-memorandum-of-understanding-on-5g-security/index.html. [↩]

- “Estonia passes ‘Huawei law’ for telecom security reviews”. Reuters. May 12, 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-estonia-telecoms-law-idUSKBN22O22I.; Electronic Communications Act. Estonian Parlament. December 17, 2020. https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/ee/528052020005/consolide/current. [↩]

- Amendments to Government Regulation No. 140 of 22 June 2006 “Requirements for the Provision of Communication Services and Technical Requirements for Communication Networks” and Regulation No. 129 of 11 December 2015 “Statutes of the Security Committee of the Government”. Ministry of Economic Affairs and Communications of the Republic of Estonia. https://eelnoud.valitsus.ee/main#AUSxaqNZ. [↩]

- “Plan for implementation of the provisions of the eighteenth government of the Republic of Lithuania”. Government of the Republic of Lithuania. March 10, 2021. https://www.e-tar.lt/portal/lt/legalAct/d698ded086fe11eb9fecb5ecd3bd711c. [↩]

- “5 key facts about 5G radio access networks”. Ericsson, 2020. https://www.ericsson.com/en/public-policy-and-government-affairs/5-key-facts-about-5g-radio-access-networks. [↩]

- “Potential threat vectors to 5G infrastructure”. U.S. Cybersecurity & infrastructure security agency. National security agency. Office of director of national intelligence. May 2021. https://www.cisa.gov/sites/default/files/publications/potential-threat-vectors-5G-infrastructure_508_v2_0%20%281%29.pdf. [↩]

- “Open RAN explained”. Nokia. October 16, 2020. https://www.nokia.com/about-us/newsroom/articles/open-ran-explained/. [↩]

- Griffith, Melissa K. “Open RAN and 5G: Looking Beyond the National Security Hype”. Willson Center. November 2, 2020. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/open-ran-and-5g-looking-beyond-national-security-hype. [↩]

- “CCDCOE to lead research on securing 5G networks for military mobility”. NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence. January 15, 2021. https://ccdcoe.org/news/2021/ccdcoe-to-lead-research-on-securing-5g-networks-for-military-mobility/. [↩]

- “NATO needs a multinational effort to secure 5G networks”. NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence. June 10, 2021. https://ccdcoe.org/news/2021/experts-concluded-that-nato-needs-a-multinational-effort-to-secure-supply-chain-and-networks-of-commercial-and-military-5g-networks. [↩]

- “Address by President of Latvia Egils Levits at the opening of the 5G in LMT”. President of the Republic of Latvia. June 19, 2019. https://www.president.lv/en/article/address-president-latvia-egils-levits-opening-5g-lmt. [↩]

- “Camp Ādaži becomes the first innovative 5G military test site in Europe”. Ministry of Defence of the Republic of Latvia. November 19, 2020. https://www.mod.gov.lv/en/news/camp-adazi-becomes-first-innovative-5g-military-test-site-europe. [↩]

- Nikers, Olevs. “5G Technologies in Latvia Advance Military Capabilities and National Economy”. The Jamestown foundation. December 15, 2020. https://jamestown.org/program/5g-technologies-in-latvia-advance-military-capabilities-and-national-economy/. [↩]

- Grinkevičius, Paulius. “„Teltonikos“ planas – 2,5 mlrd. Eur investicijų į puslaidininkių pramonę Lietuvoje”. Verslo žinios. May 21, 2021. https://www.vz.lt/inovacijos/2021/05/21/teltonikos-planas–25-mlrd-eur-investiciju-i-puslaidininkiu-pramone-lietuvoje. Degutis, Gintautas and Budreikienė Jovita. “Lietuviai mokslininkai: 6G technologijos prototipas – jau po 4 metų“. Verslo žinios January 14, 2021. https://www.vz.lt/technologijos-mokslas/2021/01/14/lietuvos-mokslininkai-6g-technologijos-prototipas-jau-po-4-metu.; “Foreign Investor of the Year 2020, Ericsson Estonia: We are helping to bring Estonian expertise to the world”. Invest in Estonia. July 2021. https://investinestonia.com/foreign-investor-of-the-year-2020-ericsson-estonia-we-are-helping-to-bring-estonian-expertise-to-the-world/. [↩]

- Thompson, Edric. “US Army, Estonia sign historic agreement for collaborative research in cyber defense”.CCDC C5ISR Center Public Affairs, September 14, 2020. https://www.army.mil/article/239023/us_army_estonia_sign_historic_agreement_for_collaborative_research_in_cyber_defense. [↩]

- “Kaptur, Kinzinger Introduce Bipartisan Transatlantic Telecommunications Security Act”. U.S. congresswoman Marcy Kaptur. May 19, 2021. https://kaptur.house.gov/media-center/press-releases/kaptur-kinzinger-introduce-bipartisan-transatlantic-telecommunications-0. [↩]

- Kochis, Daniel. “The Three Seas Initiative Is a Strategic Investment that Deserves the Biden Administration’s Support”. The Heritary foundation, February 18, 2021. https://www.heritage.org/europe/report/the-three-seas-initiative-strategic-investment-deserves-the-biden-administrations. [↩]

- “A special report: Perspectives for infrastructural investments in the Three Seas region”. Report by SpotData. 2019.https://spotdata.pl/research/download/74 [↩]

- “Daszyńska-Muzyczka: The European Three Seas region is one of the fastest growing in the world”, Three Seas Initiative Investment Fund. October 19, 2020. https://3siif.eu/news/daszynska-muzyczka-the-european-three-seas-region-is-one-of-the-fastest-growing-in-the-world. [↩]

- “The Three Seas Initiative”. Congressional research service. April 26, 2021. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/IF11547.pdf. [↩]