“The first and most important rule to observe … is to use our entire forces with the utmost energy. The second rule is to concentrate our power as much as possible against that section where the chief blows are to be delivered and to incur disadvantages elsewhere, so that our chances of success may increase at the decisive point. The third rule is never to waste time. Unless important advantages are to be gained from hesitation, it is necessary to set to work at once. By this speed, a hundred enemy measures are nipped in the bud, and public opinion is won most rapidly. Finally, the fourth rule is to follow up our successes with the utmost energy.”

– Carl von Clausewitz

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The Military Mobility Project

The Military Mobility Project, launched by the Washington-based Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA), is designed to promote the establishment of the multiplicity of conditions (legal and regulatory standards, infrastructure and military requirements, the management of risks to the security of transiting forces) needed to enable, facilitate, and improve military mobility across Europe. The project focused on five different political-military scenarios each of which was examined by a multinational working group in a series of military mobility workshops that took place between September and October 2020. Their purpose was to generate a number of substantial recommendations that, if implemented, would advance military mobility across Europe.

In an address to the Plenary Military Mobility Workshop in October 2020, Adm. Rob Bauer, the Netherlands’ chief of defense, identified the key challenges posed to his country as a transit nation for moving military forces: the need for improved infrastructure; clear and agreed rules and regulations (for dangerous goods, customs, cross-border movement permissions); military mobility relevant command and control (C2); the establishment of a 24/7 network of national points of contact across NATO and the European Union (EU), respectively; the establishment of Territorial Command authorities by transit and host nations to facilitate smooth movements along multimodal movement corridors, properly supported by logistic hubs; and the fostering of digital support and protection. This report seeks to address these and related challenges that military mobility faces in Europe in general.1

The Project’s Primary Message

Europe’s security environment changed fundamentally in 2014 as a consequence of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine and its illegal annexation of Crimea. Since then, NATO has placed renewed emphasis on deterrence and defense and made a significant effort to strengthen its posture. In view of Russia’s now-entrenched policy of constant confrontation, its use of hybrid warfare in both peacetime and during crises, as well as its growing military potential close to NATO’s borders, the Alliance must consider the simultaneous and parallel defense of several regions all of which could be at risk in a crisis with Russia. These regions stretch from Northern Norway and the North Atlantic through the Baltic Sea and Black Sea Regions to the Mediterranean. Specifically, NATO must further enhance its responsiveness and agility as well as the readiness of its military forces and be able to deploy them rapidly to provide timely reinforcement of allies in a crisis or a military conflict. Speed is of the essence. NATO also remains committed to responding effectively to crises beyond the Alliance’s borders. Given the risk that such crises could escalate rapidly, the ability to respond speedily over distance is also important.

The EU seeks to become a geopolitical actor and advance, in time, toward a so-called European Defense Union. While the EU’s focus is on the conduct of effective civil-military crisis management beyond Europe, its ability to act effectively will also require the rapid movement of forces across Europe prior to their deployment to crisis regions adjacent to the bloc’s borders and beyond. The security environment is also marked by the return of geopolitical great-power competition. One consequence of China’s rapid rise to global power status is the shift taking place in the U.S. strategic center of gravity toward the Indo-Pacific region. The United States’ European allies and partners will thus have to spend significantly more both on deterrence and defense in Europe and effective crisis management in North Africa and the Middle East.

Against this strategic background, both NATO and the EU have a clear common responsibility to establish the conditions needed for the expeditious movement of military forces throughout Europe. The primary strategic purpose of military mobility is to move forces and resources rapidly over distance and by so doing afford the political and military leadership of the Alliance options to enhance deterrence and defense or engage in effective military crisis management beyond NATO’s borders. Effective cooperation between the EU and NATO over military mobility would further strengthen transatlantic cohesion by contributing to equitable burden sharing.

Principal Factors

There are three principal factors that should drive all efforts to improve military mobility across and within Europe: high-level engagement, effective military planning, and the adoption of a whole-of-government approach. Engagement is needed at the highest levels of NATO, the EU, and European capitals, and in both the political and military domains, to lay the foundational conditions for military mobility. This is both an urgent military requirement and a political necessity. Effective military planning for the deployment of forces across Europe both in a crisis and war must take better account of national and EU legislation and regulations. There is also a vital need to exercise and test coordination and to deconflict processes prior to any emergency to ensure they function under duress and can thus meet planning timelines. Effective and rapid military mobility also demands a whole-of-government approach in all enabling nations. This would necessarily involve (inter alia) ministries of defense, interior, and transportation, as well as those private sector leaders responsible for air, rail, road, and port facilities. Fostering a whole-of-government military mobility culture through preestablished relationships will be particularly important in transit and host nations.

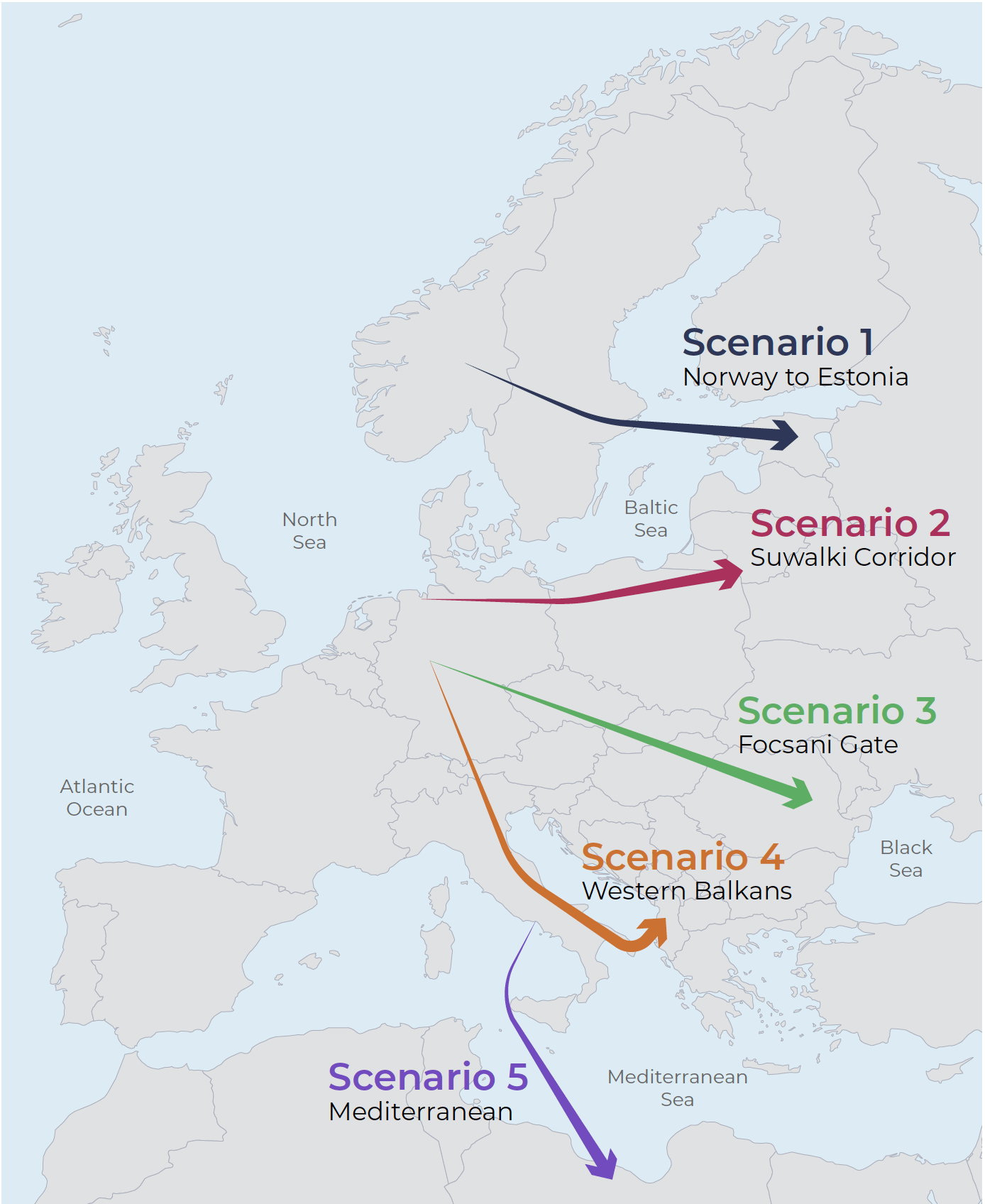

Map 1. CEPA Military Mobility Workshop Scenarios

Main Recommendations

Rules, Regulations, and Procedures

- Streamline Cross-Border Movement Permissions: It is essential that all European nations establish a harmonized cross-border movement approval process for all military movements across Europe and lift existing restrictions in national legislation. NATO has implemented a legal framework through Technical Arrangements (TAs) with both allies and its partners that participate in the Partnership for Peace (PfP) program. The European Defense Agency (EDA) and 25 EU nations are also working on two TAs, one for the surface and the other for the air domain, which are expected to be completed by spring 2021. Norway has joined the program, and it is important that other non-EU European allies join as well or at least establish compatible rules.

- Standardize regulations for the transport of dangerous goods: Legal basis for the transport of dangerous goods should be established by the EU member states and their national practices harmonized as soon as possible to promote friction-free movement. The combining of civilian rules with, where necessary, the provisions of the NATO Standardization Agreement, AMovP6, is considered sufficient by the EU. A harmonized legal basis would be particularly important for both transit and host nations. The aim should be an annual renewal/update of approval for the transport of a range of dangerous goods along defined multimodal movement corridors.

- Standardize customs procedures: All European governments should apply simplified and streamlined customs procedures for military transportation throughout Europe in peacetime and in a crisis. NATO allies and their PfP partners use NATO Form 302 for exemption from customs relating to the movement of goods for use by a deploying force. For its part, the EU has developed, in full transparency and dialogue with NATO, EU Form 302 which is to be used alongside NATO Form 302. Together, these forms enable uniform treatment of, and rapid customs declarations for, all cross-border military movements in all EU member states. However, there is concern about duplication of effort and data ownership. Therefore, in order to simplify the customs process for all military movements in Europe, NATO and the EU should make a joint effort to develop identical 302 templates.

- Accelerate response times for Cross-Border Movement Permissions: The EU aims to deliver diplomatic, border-crossing, and transit movement clearance in peacetime for military forces within five working days. For NATO, this is too long given how important it is for it to be able to respond rapidly in a crisis. NATO’s operational-level planning timeline is three calendar days (72 hours). Therefore, the EU member states should adjust their respective response times to three days. At the very least, the EU should create a mechanism to allow preapproval for defined rapid reaction force packages within a maximum of three days.

Transportation Infrastructure

- Undertake a comprehensive infrastructure assessment: The responsible headquarters/staff of both NATO and the EU should build on a comprehensive infrastructure assessment and maintain shared comprehensive infrastructure databases relevant to their respective military transportation networks. Such an approach will require close and detailed coordination with the nations. For example, host nations should continue the Military Load Classification (MLC) assessment and corresponding marking of relevant bridges.

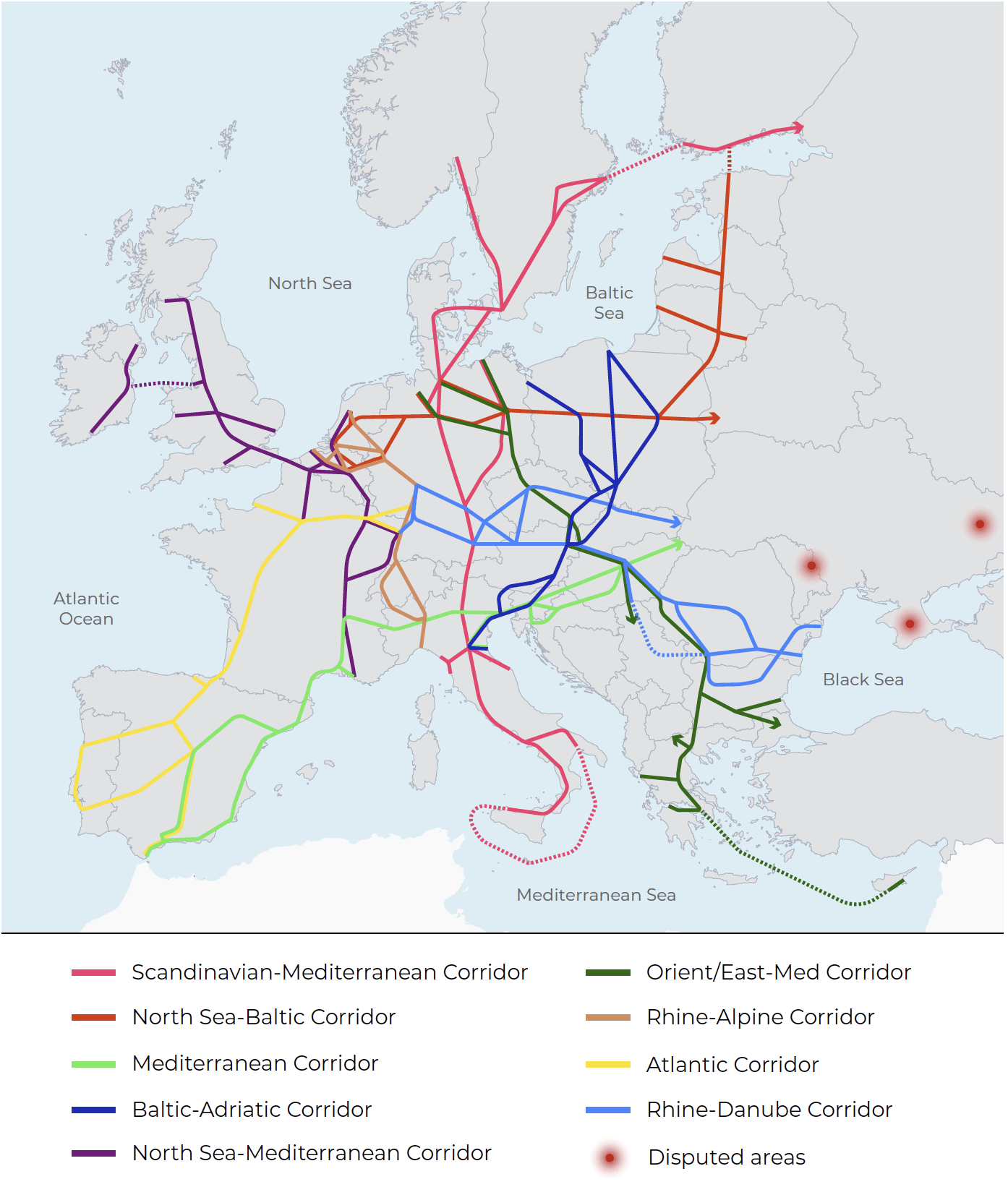

- Make full use of the European Commission’s Trans-European Transport Network policy: It is essential that European NATO allies, which are also members of the EU, in coordination with the responsible NATO military headquarters, submit project proposals for priority dual-use (civilian and military) infrastructure projects that could be co-funded by the European Commission through the military mobility envelope of the Connecting Europe Facility (CEF). Such projects will be particularly important along the main supply routes and transportation corridors and covered by the European Commission’s Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) policy. Such projects will necessarily take time and it is vital EU member states urgently identify projects that could benefit from CEF funding.

- Build for heavier military equipment: During the deployment of forces for crisis response operations weight restrictions on roads will tend to favor the use of rail or river/barge routes. This is because the combination of truck, trailer, and heavy tank could in the future exceed 120 tons. For rapid reinforcement of allies located on NATO’s periphery, transit and host nations should also better provide for sufficient bridging capability. Projects designed to reinforce bridges should be central to the creation of dual-use civil-military infrastructure throughout the EU.

- Standardize rail interfaces: The better use of civilian freight routes for military transportation should be further explored within the framework of the European Commission’s work on rail freight corridors. Over the short to medium term, increased investment in so-called transition technologies could be made to facilitate the transfer of shipments from one railway gauge to another to avoid the need to unload and reload rolling stock.

Command, Control, and Coordination

- Standardize networks of National Points of Contact: The EU has set up a network of National Points of Contact (NPOCs) for military mobility. They are the entry points for movement requests and in charge of processing them within their nations. NATO has established a network of single NPOCs at the political level to enable the coordinated management of civil emergencies and strengthen the Alliance’s resilience. NATO is also setting up a 24/7 movement control network at the operational level between it and national civil and military entities within the Alliance that is vital for force flow management for both exercises and operations. The network of POCs in NATO should be completed as soon as possible with the requisite terms of reference also finalized expeditiously. The EU POCs and those of NATO should also be aligned and harmonized as far as possible.

- Establish National Territorial Commands: Where they do not yet exist, national territorial commands (NTCs) should be established in all transit and host nations and charged with the provision of Host Nation Support (HNS) for transiting or deploying forces. Specifically, the provision of the national military infrastructure necessary for ensuring freedom of maneuver through effective rear area security, military movement control, the rapid and unrestricted crossing of waterways, including sufficient bridging capability, telecom links, and medical support should be provided. The NTCs should also act as enablers for improved links between NATO forces, national forces, and the civilian defense sector, with the NPOCs integral, but distinct elements of the NTCs.

- Make full use of NATO’s Joint Support and Enabling Command: The Joint Support and Enabling Command (JSEC) has been assigned as Supreme Allied Commander Europe’s (SACEUR’s) Joint Rear Area Command. It is in charge of battlespace management and force flow management across Europe and responsible for the security of the rear area of SACEUR’s Area of Responsibility (AOR). To this end, it should also be vested with coordinating authority for all national territorial commands and act as the network hub for the respective NPOCs for military mobility in the transit nations.

Funding

- Increase EU funding for military mobility: The EU member states concerned should make optimal use of the Military Mobility Fund (€1.69 billion in current prices) to co-fund dual-use infrastructure projects. They should also consider additional funding options, for example, by using parts of EU Recovery and Resilience Facility (RFF) funds for such projects. This would send a clear signal that Europe is serious about significantly enhancing its efforts to do more for its own security, as well as promote better transatlantic burden sharing.

- Extend NATO common funding: The Alliance should explore greater use of the NATO Security Investment Program (NSIP) to co-finance infrastructure projects relevant to military mobility that are not eligible for co-funding by the European Commission. NATO should also consider counting allies’ investments in such projects that are clearly dedicated to facilitating military mobility of NATO forces as part of a nation’s 2% (of GDP) benchmark for defense spending.

Special Capabilities

- Fully harness capability catalogs: The allies, together with NATO’s European partner nations, should make available and regularly update their respective capability catalogs. Capability catalogs are designed to ensure that nations’ data relevant to military mobility is available to NATO to inform operational and movement planning. Critical capabilities such as wet-gap crossing and counter-mobility equipment must be available in nations’ military inventories.

- Enhance national military transportation capacities: NATO should assign Capability Targets for the allies to significantly increase their respective military transportation capacity (road, rail, air, sea) and to ensure timely and assured priority access to civilian transportation capacity. EU member states should also contribute to this effort through increased collaboration via enhanced military mobility, which is one of six focus areas for collaborative capability development recommended by the EDA.

- Establish logistic hubs: Distances from ports of debarkation in Western Europe to potential theaters of operations can be great. Germany and its Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) partners should, therefore, spare no effort to implement the network of logistic hubs (for maintenance, recovery, storage of food, ammunition, and fuel, etc.) across Europe consistent with the planned establishment of multimodal movement corridors. It is essential that the logistic hubs also be fully usable by all allies contributing to NATO operations and exercises.

Resilience

- Foster a culture of cyber resilience: The deployment of military forces is particularly vulnerable to a potential adversary seeking to delay and destabilize NATO or EU responses to a crisis. Increased awareness of the cyber threat posed to military mobility should be actively promoted through better communication between NATO, the EU, the member nations, and all civilian and military stakeholders during the planning phase of operations. Far closer civil-military relationships must also be forged to ease incompatibilities between military and civilian equipment that cyberattacks would seek to exploit.

- Counter information warfare: Information warfare during a crisis, in combination with cyberattacks and subversive actions, could have significant destabilizing and paralyzing effects on Western societies as well as on allied forces. Therefore, fostering state and societal resilience against all forms of hybrid warfare, including malicious cyber activities and disinformation, is NATO’s first line of deterrence and defense and a precondition for the EU’s ability to act successfully. Host nations’ civil and military authorities, together with commanders of transiting and deployed forces, should closely coordinate to develop a common approach to countering disinformation if they are to respond swiftly and effectively.

Exercises

- Establish a systematic and comprehensive program of EU-NATO civil-military exercises: Military mobility in Europe relies on a complex system of national and international civilian and military stakeholders and actors. This system needs to be regularly tested, reviewed, and improved, both in NATO and the EU. Such a goal can only be achieved through a systematic and comprehensive program of rigorous exercising.

- Use exercises to promote a shared civil-military understanding: A variety of frequent joint military mobility exercises should be conducted to strengthen both NATO-EU and national civil-military cooperation. Such “events” would also help construct a shared civil-military understanding of the challenges faced by military mobility and ensure staff are properly trained, with processes and procedures tested and adjusted; possible vulnerabilities, frictions, and associated risks identified and addressed; and cohesion built among stakeholders.

- Test and improve NATO and national planning: Movement of NATO forces to reinforce national home defense forces of allies located on the Alliance’s periphery requires close and effective coordination between NATO and host nations to meet the requirements of tactical-level advance planning, in particular with regard to force space, and time requirements adjusted to regional/local conditions.

Persistent NATO-EU cooperation on military mobility

- Enhance the Structured Dialogue on Military Mobility: The Structured Dialogue on Military Mobility between relevant NATO and EU staffs has already effectively contributed to improved information sharing in key areas such as transportation infrastructure, the transport of dangerous goods, customs, and cross-border movement permissions. However, those involved should meet more frequently and focus on identifying those areas and measures that must be tackled urgently in order to make tangible progress. To that end, a virtual joint secretariat could be charged with monitoring progress between the meetings and coordinate technical staff cooperation on particular strands of work between the meetings to ensure issues are followed up.

- Senior leadership engagement is essential: Key leaders’ engagement is vital. The NATO secretary-general and the presidents of the European Council and the European Commission must be regularly informed about progress achieved and the emerging issues that can only be tackled at their level of responsibility. They should also be encouraged to address issues vital to military mobility in their meetings and provide guidance to their respective civil and/or military staffs.

Map 2. Trans-European Transport Network

FOREWORD

By Ben Hodges

Effective deterrence requires demonstrated capability and the will to use that capability. It must be built on a strong foundation of speed: (1) speed of recognition of what a potential adversary is considering, (2) speed of decision-making to begin necessary movements and preparations to prevent or respond to a crisis, and (3) speed of assembly to gather the elements of combat power in place to stop an adversary or, if deterrence fails, to respond fully and forcefully.

Military mobility is essential to effective deterrence. It is about speed and the ability to move our forces as fast or faster than any potential adversary. It gives political leaders options to head off a crisis and the ability to deter — something other than a liberation campaign.

CEPA’s Military Mobility Project was a yearlong, comprehensive look at all facets of military mobility, including authorities, capabilities, capacities, transportation infrastructure, cyber protection, air and missile defense, mission command, interoperability, river crossings, weights of vehicles, EU regulations, and NATO decision-making. The project included panels that were conducted virtually over the spring, summer, and fall of 2020 as a consequence of Covid-19 pandemic-related restrictions. Its center of gravity was the Military Mobility Workshop, which was also conducted virtually, in August, September, and October.

The workshop was unique in several ways. It was based upon five different scenarios which touched nearly every corner of Europe within a NATO or EU context. Each scenario included cross-functional working groups of 15-25 practitioners and experts from a wide range of organizations, agencies, industry, media, and nations. The results were presented during a virtual culminating event in October with the workshop’s senior mentors and working group leaders, and alongside presentations by Adm. Rob Bauer, the Netherlands’ chief of defense, and Lt. Gen. Scott Kindsvater, deputy chairman of the NATO Military Committee.

This project was also the first to gather a comprehensive list — or “network” — of organizations, agencies, and industries that have a role and stake in improving military mobility. This network will enable and enhance further work in the coming months and years.

This report provides key findings, sharp analysis, and substantive, achievable recommendations to reinforce and build upon existing efforts. Much progress has been made, and relevant headquarters, nations, and responsible NATO, EU, and national leaders now acknowledge the significance of military mobility to our credibility. But we have yet to meet all requirements for effective deterrence. There is insufficient capacity and capability, authorities are still not complete, and determining clear chains of command remains a major problem.

NATO, the EU, and the member nations have a common responsibility to make effective military mobility a reality. We hope that the substantive recommendations offered in this report will be considered and, in time, implemented so that we can move as fast or faster than our potential adversaries.

STRATEGIC CONTEXT

Since 2014, the security environment in and around Europe has fundamentally changed. For NATO, new challenges and threats have emerged from two strategic directions. To the east, Russia’s aggressive actions against Ukraine and its illegal annexation of Crimea profoundly altered the conditions for maintaining security in Europe. To the south, an “arc of instability” and violence stretching across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) fueled terrorism and triggered mass migration, both of which affected the stability of Europe. Consequently, NATO must be able to respond to multiple challenges and threats from several regions and directions at short notice. In order to do so, the Alliance must ensure it has the right forces in the right place at the right time. While the two major sets of challenges are different, they are equally important for the security of NATO allies. Therefore, NATO has adopted a multi-faceted approach. First, the Alliance is significantly strengthening its deterrence and defense posture, particularly its ability to rapidly reinforce allies on its periphery, if necessary. Second, the Alliance is projecting stability to its southern neighborhood, primarily by supporting partners therein to develop their own defense capacities, but also by undertaking crisis response operations, if needed. In addition, the Alliance is bolstering its resilience against hybrid threats from state and non-state actors, in particular by strengthening its cyber defense and countering disinformation.

By way of its conclusions on how the EU Global Strategy should be implemented, the European Union (EU), in November 2016, determined the three strategic priorities to be pursued by it in the area of security and defense: responding to external conflicts and crises, building partners’ capacities, and protecting the bloc and its citizens. To that end, the EU has adopted a range of measures to “build a more effective, responsive and joined-up Union, capable of pursuing the EU’s shared interests and priorities in promoting peace and guaranteeing the security of its citizens and territory.”2 In November 2017, the EU agreed to undertake an initiative to improve and enhance military mobility. One of the practical steps proposed was the better exploitation and fostering of civil-military synergies and the greater use of existing policies and instruments to “enable EU Member States to act faster and more effectively in the context of the Common Security and Defense Policy, national and multinational activities.”3 Moreover, work is underway on the EU Strategic Compass. Based on a joint threat analysis, this new EU security policy document, which is due in 2022, aims to specify how the priorities set by the EU Global Strategy can be implemented and which capabilities the EU should provide with respect to crisis management, enabling and enhancing partners, and protecting the Union and its citizens.

There are, of course, wider strategic considerations both in the transatlantic relationship and beyond, most notably the evolution of the global security environment and growing great-power competition. Of specific relevance to this project is the growing worldwide overstretch to which U.S. forces are subject. U.S. armed forces are perhaps as taut as at any time since the Korean War in the early 1950s, or at least the Vietnam War in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Given the nature and scope of the change, the security and defense of Europe will become progressively harder to maintain credibly unless Europeans, in concert with their North American allies, quickly take practical steps to ensure their ability to act as effective, fast first responders during a crisis. Improved military mobility would represent one strand of effort, albeit a vitally important one, in reinforcing defense and deterrence. Enhanced military mobility would also demonstrate a European determination to ease the burdens and overstretch to which U.S. forces are subject. In the worst case, U.S. forces could face simultaneous engineered crises in the Indo-Pacific, the Middle East, North Africa, and the Euro-Atlantic. Given the changing correlation of forces there could come a point when the United States might be unable to prevail in any of these conflicts unless properly supported and aided by its European allies, particularly in and around the European theater. Therefore, the strategic ambition implicit in the Military Mobility Project is the possible need for European forces to hold the line in a series of crises precisely so that the United States could use its own forces to best effect.

EUROPE’S MILITARY MOBILITY CHALLENGE

There is a sobering story about Europe’s contemporary military mobility challenge. A U.S. Army force of Bradley armored infantry fighting vehicles was being transported by train across Poland. Each of the Bradleys was equipped with a so-called Commander’s Sight device that projected from the top of the hull of each vehicle. The route had been “recced” to ensure the necessary clearances. Every single bridge, tunnel, and overpass had been carefully measured, except one ….

Drive across Western Europe during the Cold War and one could have seen signs on thousands of road bridges bearing the image of a tank and a number. The sign signified the weight and gauge any given bridge could bear in the event of a major exercise or an emergency. In what is today’s Western Germany, major exercises designed to test military mobility were almost routine with REFORGER I-IV, Lionheart, Able Archer, and Big Lift part of a coterie of exercises the commanders of which all assumed that road, rail, air, sea, and port facilities, much of it controlled by a civilian government, would enable their respective forces to move rapidly and relatively securely. Those days are gone. For example, since the end of the Cold War, much of the rail infrastructure across Europe has been privatized, mainly to comply with EU competition and state aid rules. The shift to a corporate culture with its focus on commercial cost and profit has led to entire infrastructures being constructed with no heed for their potential military use in an emergency.

In Central, Eastern, and Southern Europe the situation is even worse as such infrastructure never existed. During the Cold War, the Group of Soviet Forces, Germany (GFSG) might have looked impressive on paper. However, its commanders consistently fretted about the difficulty of secure supply and resupply given the poor condition of much of the infrastructure between Russia’s western border and its forward-deployed forces. Indeed, such concerns partly explain the Soviet penchant for the offensive and the doctrine of “proval blitzkriga,” which supported it for much of the Cold War. First, the force would need to live off the land of others if it was to maintain both momentum and cohesion. Second, the security of its rear area deteriorated across much of Central Europe as Warsaw Pact nations became increasingly fractious.

The challenge of military mobility is not just one of physical weakness. There are a host of political and legal barriers that prevent the rapid deployment of military force across national borders in Europe, both during peacetime and the conduct of routine activities and exercises, but also during crises. Consequently, allied forces take far longer to deploy and be retrieved than they should if they are to afford contemporary deterrence and defense, the hard power credibility upon which both depend.

The challenge is being slowly addressed. In March 2018, Federica Mogherini, at the time high representative of the EU for foreign affairs and security policy and vice-president of the European Commission, together with then-European commissioner for transport, Violeta Bulc, presented the “Action Plan on Military Mobility.” This action plan outlines concrete steps to better facilitate and expedite the movement and crossing of borders by military personnel, materiel, and equipment both for routine activities in peacetime and during crisis and conflict, both within and beyond the EU. The action plan considers all transport modes and in all strategic directions. Moreover, Bulc stated: “[O]ur objective is to make better use of our transport network, to ensure that military needs are accounted for when planning infrastructure projects. This means a more efficient use of public money and a better-equipped transport network, ensuring quick and seamless mobility across the continent. This is a matter of collective security.”4

The action plan addresses specific areas germane to this project: transport infrastructure; regulatory and procedural issues, such as transport of dangerous goods, customs, and value-added tax, and cross-border movement permissions, including diplomatic clearances; and other cross-cutting topics such as countering hybrid threats. The subsequent military requirements for military mobility within and beyond the EU were developed by the EU Military Staff in close cooperation with the EU member states, as well as the European Commission and the European Defense Agency (EDA). Critically, the relevant NATO staffs were also engaged and involved. The method of the action plan was to use infrastructure development to create synergies between civilian and military transportation needs. Consequently, a “gap analysis” was undertaken to establish a relationship of need between military infrastructure requirements and civilian requirements addressed by the European Commission’s Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) policy. The analysis identified a significant (93%) overlap between the infrastructure identified as relevant for military purposes and the geographic scope of the TEN-T. The overlap also helps define the geographic coverage needed for dual-use (civilian and military) projects that could be eligible for co-funding by the European Commission’s Connecting Europe Facility (CEF) with a view to enhancing both civilian and military mobility.

Work is ongoing to identify suitable dual-use projects with the funding of projects beginning possibly as early as 2021 (in accordance with the October 19, 2020, joint report by the European Commission and the High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy to the European Parliament and the European Council). Therefore, EU member states have been invited to identify and present their priority dual-use infrastructure projects, while the European Commission and the EDA are also examining streamlining and simplifying customs arrangements for military movements, as well as better aligning rules concerning the transportation of dangerous military goods across borders. The EDA has also been charged with supporting the establishment of common rules on cross-border movements of military forces.

While the stated ambition is impressive, political agreement on funding proved more difficult. The European Commission had originally proposed €6.5 billion of co-funding for dual-use infrastructure projects through the CEF as part of the EU’s Multi-Annual Financial Framework (MFF) for 2021-2027. However, during the long and difficult negotiations on the size and various elements of the new MFF and concomitant contraction of the EU budget by some 16% due to the departure of the United Kingdom as a result of Brexit, the CEF’s military mobility envelope has been reduced significantly to €1.69 billion (in current prices) for 2021-2027.

Military mobility is also among the 47 EU Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) projects, part of the EU’s overall effort to “develop defense capabilities and improving the operational availability of forces.”5 The PESCO military mobility project is led by the Netherlands and supported by 24 other EU member states, which are project members. At its core is the concept of a “Military Schengen” — the free movement of military units and assets throughout Europe as a result of the removal of bureaucratic barriers and improvements to the infrastructure needed to move through EU member states, via rail, road, air, or sea. On the one hand, the PESCO military project demonstrates the broad political support that enhancing military mobility enjoys. On the other hand, there is a multiplicity of EU entities and national actors involved which poses significant challenges for cohesion and coordination.

It is critical that the capabilities, infrastructure, and arrangements necessary to support the deployment and sustainment of NATO forces are in place in advance. The vital role of the Alliance is as a force generator, but NATO’s ability to act is only credible if it can act. With the important exception of Rapid Air Mobility, NATO looks to its members and the EU to create the necessary infrastructures and permissions that are vital to enabling such action. To that end, NATO is engaged in similar planning to that of the EU as part of its Enablement Plan for SACEUR’s Area of Responsibility. Timely reinforcement of a threatened ally or allies to strengthen deterrence in a crisis and/or effective defense in a war rather than permanent forward positioning of large forces has been, and remains, the paradigm for adapting NATO’s conventional force posture. Hence, enabling military mobility has become a priority area for enhanced NATO-EU cooperation within the framework of the implementation of the 2018 Joint Declaration signed by the presidents of the European Council and the European Commission and the NATO secretary general to promote cooperation in areas that are crucial for the security of both the EU and NATO. The US-led Exercise Defender 20 would have tested many of the Alliance’s assumptions about military mobility, but in a sign of the times it was curtailed due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

THE PRINCIPLES OF MILITARY MOBILITY

Two principles remain central to effective and efficient military mobility: speed of assembly and speed of engagement. The master principle of military mobility concerns the ability of combat forces and their weapons to move expeditiously toward their objective, and for combat support and combat service support forces to maintain the fighting efficiency of such a force once engaged. Future war will place a particular premium on the ability of combat forces to move rapidly and securely. Over the past century, the pace and reach of military mobility has gone from the pace and range a regiment or unit could walk to rapid air mobility. With the increasing use of robotics and automation in the battlespace, it is likely that future military mobility could take place at hyper speed. Consequently, the speed of command is accelerating as well as the distance from which such a force can be attacked by increasingly “intelligent” systems, which poses a range of challenges for military mobility because forces will be at their most vulnerable during a war when they move into position.

Military mobility has always been seen as a force and combat multiplier enabling commanders to choose the space in which to fight. From the English longbowmen of the 13th to 15th centuries to the Wehrmacht of World War Two the ability of a force to move rapidly has historically enabled a force to defeat a more cumbersome enemy many times its size. With the shift toward future war across air, sea, land, cyber, space, information, and knowledge the very concept and principles of “mobility” are changing. What is to be moved by whom, where, when, and how and against whom and what threat requires a new mindset of mobility. In such an environment the past “luxury” of commanders to amass a force on one site over many days will evaporate as mobility accelerates for both the offense and defense. Moreover, the movement of force and resources is increasingly vulnerable to new forms of coordinated attack from cyber and information “warriors” across a vast field of engagement. Consequently, a deploying force could be attacked anywhere along any route effectively halting military mobility. Therefore, fostering state and societal resilience against all malicious cyber activities and disinformation is key to credible deterrence and thus constitutes NATO’s first line of defense. It is also a precondition for the EU’s ability to successfully deploy forces for crisis management.

In sum, central to the success of military mobility is the creation of secure military movement corridors through which forces must pass to exploit their mass and to maintain speed of command and action. Carl von Clausewitz saw military mobility as central to sound strategy. For him, strategy involved the identification of the decisive space in which to fight an enemy and the preservation of a commander’s ability to move forces as he so wished. Indeed, for Clausewitz strategy involved choosing the space and time in which to fight, while tactics concerned the successful conduct of the fight once engaged. Military mobility was thus central to his principles of warfare.

POLITICAL-MILITARY FRAMEWORK IN EUROPE

Effective military mobility is also central to NATO’s mission spectrum, particularly at the high end of conflict. This is because NATO remains solely responsible for collective defense planning and operations as part of which, and as a matter of principle, Article 5 collective defense operations enjoy absolute priority. However, enhanced military mobility also enables allies to maintain their contributions to crisis response operations lower down the conflict spectrum. Effective and credible military mobility is thus also central to meeting the requirements of European security and defense established within the framework of the EU’s Common Security and Defense Policy (CSDP), particularly as it concerns the effective and timely deployment and sustainment of civilian and military means for crisis response in regions beyond the EU’s borders.

Rapid and effective military mobility thus acts as a deterrence and defense enabler and force multiplier in its own right. For example, improved military mobility would better enable the activation of the relevant NATO Graduated Response Plans (GRPs), specifically the movement of the Very High Readiness Joint Task Force (VJTF, a brigade-sized joint force of some 5,000 troops) and the remainder of the NATO Response Force (NRF) in support of the national home defense forces and forward-deployed NATO forces to designated areas. This is particularly important for the Baltic states and other regions along the northern, eastern, and southeastern borders of the Alliance. It would also enable the more rapid deployment of reinforcing “follow-on forces,” such as additional mechanized forces held at a very high readiness as part of the NATO Readiness Initiative. Improved military mobility would render greater utility of allied forces and thus broaden the range of options for the political leadership to ensure an appropriate, effective, and proportionate response. Consequently, the value of improved military mobility extends far beyond the movement of any force package as it would further assure and ensure allied decision-making in the eyes of allies, partners, and, critically, adversaries. The ability to act is a critical factor in the maintenance of credible deterrence.

Improved military mobility would also give political leaders and military commanders greater flexibility through more phased responsiveness and graduated readiness in crises. For example, moving from air policing to air defense during a crisis requires that NATO air forces can be deployed without delay across Europe. Therefore, the arrangements for NATO’s Rapid Air Movement (RAM) across national borders in Europe must be such that border crossings can take place at very short notice. Timely allied air movement is thus a condition for friction-free military mobility that has already been established.

Such movement also reinforces the need to move all allied forces rapidly in the event of a military attack. However, while air movement by its very nature depends on specific infrastructures, the mobility of land forces can only be credible if the infrastructures and systems that enable it are sufficiently robust, the network endowed with sufficient redundancy, and, above all, if the necessary infrastructures and permissions are in place. Legality of movement is thus a critical enabler of defense and deterrence. The legal basis for an Alliance response is under Article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations (U.N. Charter), the right to self-defense. Article 51 permits an immediate response by both national home defense forces and the legitimate alliances of which they form a part. In the event of a surprise attack this would concern all of NATO’s various commands and forces in and around the Euro-Atlantic area, including forward-deployed U.S. forces. Indeed, central to the legal ethos of the Alliance is that an attack on one ally is an attack on all. In practice, Article 51 would buy time for a considered decision by the North Atlantic Council (NAC) on the nature, scope, and extent of any attack and thus for the Alliance to respond proportionately, including the possible and eventual invocation of Article 5 of the Washington Treaty. Consequently, improved military mobility, both to theater and within it, would not only make NAC decision-making more credible it would also afford leaders more utility and flexibility in the use of conventional force (which today extends across the information and digital spectra) prior to any cataclysmic decision to use nuclear weapons.

Furthermore, sound security and defense are increasingly reliant on a shifting balance between people protection, military power projection, and legal authorization. This balance also demands a new “contract” between critical civilian and military actors. As the Covid-19 crisis has shown, the need to move resources quickly and intelligently across the European theater is vital to responsiveness across a broad spectrum of security. However, vital political nuance in a complex crisis can be frustrated if structures and systems on the ground are simply unable to meet the demand of response due to a lack of alignment between the political, the legal, and the physical.

In the event of a planned crisis response operation by NATO beyond its borders the legal basis for action would be constituted by a series of sequential NAC decisions. Critically, for any such crisis response operation member nations would in the end almost certainly also demand a mandate from the U.N. Security Council. In the EU, any decision to act would be taken by the Political and Security Committee (PSC), based on Article 38 of the Treaty of the European Union and under the responsibility of the Council of the EU and the high representative. Additionally, a so-called joint action would also need to be agreed that specifies the mandate and details of such a mission in legal terms, i.e., consistent with the Treaty of the European Union and, of course, the U.N. Charter. Consequently, for both NATO and EU/CSDP crisis response operations most of the nations concerned would insist upon a U.N. mandate.

Given the tensions therein if nations are unwilling to act prior to U.N. authorization responsiveness and mobility could be halted. Given also that adversaries such as China and Russia are becoming increasingly skilled at operating just below the threshold of Article 5, the Alliance must further confront a crisis of legitimate action implicit therein. When would it be legitimate to act in the absence of a U.N. mandate? For example, if the U.N. Security Council was stymied by a Chinese or Russian veto the ability of both NATO and the EU to act would be strengthened immeasurably if both institutions not only had the credible ability to respond to crises in a quick and timely manner, but also applied some “creativity” over the source of legitimacy for any such action.

Ultimately, the case for improved military mobility rests on several dangerous realities given the nature and scope of emerging and disruptive challenges and threats faced by Europeans and their partners: the growing overstretch of U.S. forces and the concomitant shift of the United States’ strategic center of gravity to the Indo-Pacific region, the relative paucity of deployable European forces, and their limited collective ability to move forces and resources quickly to offset relative weakness. Rapid and assured military mobility is thus one of the essential pillars upon which any credible overall strategic framework for security, defense, and deterrence in Europe would need to stand, the more so given the possible concurrency of crises in a major emergency.

In the event of escalating political and military tensions during which there are a number of indicators that suggest Russia is preparing to launch a large-scale attack, NATO would also need to be prepared to confront aggression in more than one region. Consequently, the Alliance also has to set priorities of scale and the readiness of the forces and resources required, as well as establish timelines for the rapid deployment and buildup of forces in more than one region. It would be assumed that NATO had some time to assess, decide, deploy, and employ forces to reinforce deterrence or conduct collective defense operations. Consequently, the critical need would be for leaders and commanders to know what could be moved where, at what scale and speed, and, critically, how best to move forces and resources appropriately to ensure secure and credible “notice to effect.” It would be difficult but doable. However, if NATO was confronted with a short-notice crisis or attack by Russia, and a fait accompli, possibly in the Baltic region, the challenge for military mobility would be profoundly different and more difficult. NATO’s immediate response initially would be to authorize the speedy deployment of sufficient forces to reinforce the Baltic states and Poland to deter Russia from attempting a quick land grab and to deny it the possibility of further incursions. Any such contingency would thus require the planning, generation, and deployment of a sizable and powerful force in far less than thirty days.

During a high-end emergency, for example in the Baltic states, allied forces would need to cross the Suwa?ki Corridor and move further to the north. NATO would also need to be prepared to move the VJTF and/or even the entire NRF forward as far as Estonia if need be. However, if war were to break out while deploying the force the conditions for the movement of all allied forces would change fundamentally and dramatically. Russia would have activated its burgeoning anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) capability in Kaliningrad and the St. Petersburg area, as well as on the Crimean peninsula, significantly hampering the movement of NATO’s forces. Even as they deployed, NATO forces would also be confronted with the full spectrum of Russia’s (hybrid) warfare capabilities, including cyberattacks, disinformation, subversive actions, blockages, deep strikes with intermediate-range missiles, etc. Such actions would also massively impact the deployment of NATO’s air and maritime forces, the composition and readiness of land forces to be deployed, and how and when they would or could move. In other words, NATO would be forced to adopt maneuver operations in significant scale in-depth at an early stage of any major conflict across a space that would extend from the rear area to the forward defense area all of which would be under various forms of an intense Russian attack.

In planning for such worst-case scenarios, a number of questions must be addressed, such as: What type and quantity of force and materiel would need to be transported to meet the threat? How would control, execution, and monitoring of military and civilian movements be secured? Who would have the full picture of all multimodal capacities and their availability in such a crisis? Could a robust chain of command be established in the face of deep cyberattacks, engineered social disorder, organized criminal and terrorist attacks, and, of course, direct military attack?

MILITARY MOBILITY PROJECT — FIVE SCENARIOS

It is against the backdrop of a challenging contemporary strategic context that the Military Mobility Project was established. The essential dilemma faced by NATO is this: While the Alliance’s 30 member nations provide far more aggregated military power compared to Russia they are disaggregated through geography, command, and structure, as well as varying levels and types of strategic culture. Russia, on the other hand, can choose where, when, and if to apply locally overwhelming force anywhere on the perimeter of both the EU and NATO. Given that potentially critical allied disadvantage, effective and efficient military mobility is a critical element of credible deterrence and defense, as well as regional emergency management, as evinced by the response to the Covid-19 pandemic. While NATO has made significant progress in adapting to a changing strategic environment, and the EU has devoted a significant effort to improving military mobility by means of implementing the Action Plan for Military Mobility, far more needs to be done given the evolving nature of the threat.

The Military Mobility Project was designed to identify key findings and recommendations that would, if implemented, advance the conditions required to enable military mobility across Europe. The project’s core assumption was that effective and efficient military mobility across road, rail, sea, and air would far better support and enable a range of contingencies from a peer competitor crisis in Europe to the consequences of political, economic, and social collapse in the Middle East and North Africa and the threat posed by terrorism.

With this in mind, the project established five scenarios. Three of the scenarios addressed high-end military dilemmas in varying forms in response to a possible threat from Russia, all of which would require the use of significant force, while the other two scenarios considered the use and utility of military force across a much broader spectrum of civil-military interventions. The aim of the scenarios was to test military mobility across differing conditions, environments, and challenges within the overall political and strategic context established herein.

The scenarios shared a range of characteristics and differences. They were all potential flashpoints, had strategic implications for the security and defense of Europe, and demanded a tailored and intelligent application of force and resource over time, space, and mission intensity. They would also likely be subject to complex strategic coercion prior to full-scale military conflict across the hybrid cyberwar spectrum of disinformation, deception, destabilization, disruption, and implied or actual destruction. Equally, they were also sufficiently different and distinct enough to pose a range of institutional, national, and military mobility challenges.

Each scenario was assigned to a working group composed of multinational, cross-functional, civilian, and military integrated teams of some 20 personnel. They all enjoyed representation from the EU, NATO, member nations, industry, media, and academia, and included specific subject matter experts in areas such as cyber, transportation, and logistics. The aim of the working groups was not to “solve” any political or strategic issues, but to examine what was required to deploy a force using complex multimodal modes of transport (air, sea, road, and rail). The objective was to generate the concrete recommendations for which this report is a vehicle, to use the report thereafter to raise awareness across and amongst a swathe of policymakers of the critical importance of military mobility, and to generate a much-needed sense of urgency.

Scenarios I (the Nordic-Baltic Route), II (the Suwa?ki Corridor), and III (the Foc?ani Gate) tested the movement of forces for reinforcement of eastern allies located on NATO’s northeastern and southeastern flanks. They were based on the political-military framework set by NATO’s political leaders at various summits, such as the 2016 Warsaw Summit where the heads of state and government agreed to establish two forms of multinational forward presence: an Enhanced Forward Presence (eFP) and a Tailored Forward Presence (tFP). The eFP was established to reinforce the Baltic states and Poland, all of which share common borders with Russia and could be exposed to a potential direct military attack by Russia. The eFP comprises several multinational battlegroups ready to “fight tonight.” The tFP in Romania and Bulgaria committed allied forces to reinforce the defense of NATO members not directly exposed to a potential military attack by Russian forces. The tFP saw the creation of a Multinational Divisional HQ (South-East), as well as a Multinational Brigade HQ (South-East), plus roughly two battalions. It also acts as a framework for the regular exercising of multinational allied forces in the region and includes an enhanced NATO air and naval presence in the Black Sea Region. The difference between the two forms of “presence” is essentially one of time. In the event of an attack on NATO’s southeast, Russia would either need to launch a large-scale amphibious landing operation from Crimea or first defeat Ukrainian forces before crossing Moldova to invade Romania, all of which would imply significant preparations, large forces, and significant time. Consequently, NATO would likely have time to prepare its collective defense of the region, albeit subject to the constraints on military mobility environment being sufficiently permissive for NATO to reinforce national defenses in the region that is notorious for poor communications and transportation links. However, while the Alliance force posture in both the eFP and tFP reflects headquarters and forces at different states of readiness, for the sake of methodological rigor each scenario tested assumptions to the credible worst-case for each of them.

Scenarios IV (Western Balkans) and V (Libya) specifically tested the planning assumptions of the EU with regard to a possible crisis response beyond their respective borders. However, while Scenario IV dealt with reinforcing the EUFOR mission in Bosnia and Herzegovina (Operation Althea) to fend off possible Serbian and Russian destabilization activities and restore stability across the Western Balkans, Scenario V envisaged an autonomous EU peacekeeping mission without recourse to NATO assets and capabilities. The assumption therein being that there would be no Berlin-Plus missions beyond the existing one in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Consequently, the scenario considered how best to deploy a relatively small force package across a large geographical area using unhardened existing arteries.

Scenario I examined the movement of a defined NATO force package from Norway through Sweden and across the Baltic Sea to the Baltic states and Poland. Its focus was the political, legal, organizational, and infrastructural challenges that would be faced moving a battlegroup from Oslo to Stockholm and on to Estonia. Scenario II examined the movement of military forces from Germany through Poland to the Baltic states. The focus of the scenario was the so-called Suwa?ki Corridor through which allied forces would need to pass. Some 40 miles (60 kilometers) wide and stretching along the Lithuanian-Polish border between Belarus and Kaliningrad, the Suwa?ki Corridor could become a choke point for allied forces and cut across NATO’s land supply axis to the Baltic states. Defending the Baltic states and Poland has moved the AOR far to the east of where it was at the end of the Cold War. And yet, only two roads and one railway line through the Suwa?ki Corridor would enable NATO land forces to reinforce the region across land. Scenario III tested reinforcing NATO’s southeastern region, in particular the movement of forces across the Carpathian Mountains and the utility of the River Danube for military transport to the so-called Foc?ani Gate — a terrain basin that is suitable for maneuver operations and also offers a military force that would be able to penetrate the gate from the east to gain an avenue toward the Western Balkans. The essential challenge was to get allied forces into the region in strength and in time. The infrastructure that would enable such movement is by and large old with some of the POD under Russian influence.

Scenario IV concerned an EU-led operation, supported by NATO assets and capabilities that had to be moved across Europe to the Western Balkans to restore stability and counter Russian influence therein. The focus was on the movement and use of military forces in a complex strategic environment in which hybrid warfare and military competition were destabilizing an already unstable the region. Finally, Scenario V tested the manifold technical, logistical, and military challenges of moving a force across Europe and the Mediterranean Sea into a region beyond Europe’s borders which has long since been subject to instability, conflict, and civil war. For the purpose of the scenario, the international community decided on an U.N.-sanctioned ground operation with an EU force at its core charged with keeping armed militias apart.

MILITARY MOBILITY PROJECT TEAM

The multinational Military Mobility Project Team combined experience and knowledge and was structured thus:

Project Co-Leaders:

Ben Hodges, Pershing Chair in Strategic Studies, Center for European Policy Analysis (United States)

Lauren Speranza, Director, Transatlantic Defense and Security Program, Center for European Policy Analysis (United States)

Advisers:

Julian Lindley-French (United Kingdom) (lead report author)Heinrich Brauss (Germany) (lead report author)Oliver Gnad (scenario design) (Germany)Miriam Ludwig (scenario design) (Germany)

Project Staff:

Christina Brown (United States)Candace Huntington (United States)Gabrielle Moran (United States)Carsten Schmiedl (Germany/Canada)Miruna Sirbu (Romania)

Working Group Leaders:

Scenario I: John Agoglia (United States)Scenario II: Jacek Bartosiak (Poland)Scenario III: Phillip A. Petersen (United States)Scenario IV: Greg Melcher (United States)Scenario V: Hans Damen (Netherlands)

Industry Partners:

General Dynamics European Land SystemsAcrow Corporation of AmericaDB CargoOshkosh DefenseRaytheon Missiles & DefenseRheinmetall Defence

Participating Organizations:

- Army of the Czech Republic — J4 Logistics

- Atlantic Council

- Bell Textron

- Boeing Defense, Space & Security

- Booz Allen Hamilton

- BRK Systems SRL, Craiova

- Deutor Cyber Security Solutions GmbH

- Die Rheinpfalz GmbH & Co. KG

- EURACTIV

- European Commission — Directorate-General for Mobility and Transport (DG MOVE)

- European Defense Agency (EDA)

- European External Action Service (EEAS) — European Union Military Staff; Security and Defense Policy Division

- European Parliament — European Parliamentary Research Service; Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) and Connecting Europe Facility (CEF)

- Friends of Europe

- George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies

- German Federal Armed Forces — Mountain Engineer Battalion; Joint Support and Enabling Service Headquarters (JSES)

- Ignitis Group

- International Centre for Defence and Security (ICDS)

- Lithuanian Railways — LG Freight Transport

- Ministry of Defense of Latvia — Crisis Management Department

- Ministry of Defense of the Netherlands — Task Force Logistics

- Movement Coordination Centre Europe (MCCE)

- Multinational Corps Northeast Headquarters (MNC-NE), Joint Engineering (JENG) Division

- National Defense University (NDU)

- NATO Allied Joint Force Command Naples (JFC Naples)

- NATO Defense Planning and Policy Division (DPP)

- NATO Energy Security Center of Excellence (ENSEC COE)

- NATO Force Integration Unit (NFIU) Lithuania

- NATO Force Integration Unit (NFIU) Poland

- NATO International Military Staff, Logistics, Armaments & Resources Division (IMS L&R)

- NATO International Military Staff, Defense Policy and Planning Division, Enablement & Resilience Section (ERS)

- NATO Joint Force Command Brunssum (JFC Brunssum), Movement and Transportation (M&T)

- NATO Joint Support and Enabling Command (JSEC)

- NATO Standing Joint Logistics Support Group (SJLSG)

- NATO Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE) — Strategic Enablement Directorate (STREN), Infrastructure & Engineering (IE); J4 Logistics

- New Strategy Center

- RAND Corporation

- SEKO Logistics

- Swedish Defense Research Agency

- United States Army Europe — 21st Theater Sustainment Command, G4 Mobility Division

- United States European Command — J4 (Logistics)

PROJECT TIMETABLE

The project timetable was severely impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic. It was originally envisaged that the bulk of the work would have taken place at a major Brussels conference in spring 2020. However, the Covid-19 lockdown forced the postponement of the conference. In the end, it was decided to generate the work through several virtual working group sessions which took place between the end of August and October 2020, with a culminating virtual plenary conference on October 20. Over the course of the spring and summer, CEPA hosted a number of virtual panels each month in order to create awareness, build momentum toward the virtual Military Mobility Workshop, and further inform the effort. The following panels were conducted:

- July 7, 2020: “How We Move: Five Scenarios That Test Military Mobility Across Europe,” moderated by retired Lt. Gen. Ben Hodges, Pershing Chair in Strategic Studies, CEPA ; speakers: Dr. Jacek Bartosiak, CEO and founder, Strategy&Future; Dr. Oliver Gnad, managing director, Bureau für Zeitgeschehen; Miriam Ludwig, program manager, Bureau für Zeitgeschehen; and Charles “Bill” Robinson, chief of Integrated Learning, Joint Wargaming and Experimentation Division, Joint Staff, J7.

- June 2, 2020: “Cybersecurity and Critical Infrastructure,” moderated by retired Lt. Gen. Ben Hodges, Pershing Chair in Strategic Studies, CEPA ; speakers: retired Col. Tom Greenwood, research staff member, Institute for Defense Analyses (IDA); Edvinas Kerza, corporate resilience service director at Ignitis Group, former deputy minister of defense of Lithuania; Col. Jaak Tarien, Estonian Air Force, director of NATO Cooperative Cyber Defense Centre of Excellence; and Sabina Wolf, journalist, Bayerischer Rundfunk, ARD.

- May 5, 2020: “Shifting Towards ‘Crisis Mobility?’ Why Military Mobility Matters During Covid-19,” moderated by retired Lt. Gen. Ben Hodges, Pershing Chair in Strategic Studies, CEPA; speakers: Jacek Bartosiak, CEO and founder, Strategy & Future; Tania Latici, policy analyst, European Parliamentary Research Services; Greg Melcher, chief operations officer, New Generation Warfare Centre; Gp. Capt. Elizabeth Purcell, J4 Strategic Plans, NATO Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE).

- April 2, 2020: “Moving Mountains Amid a Crisis? Increasing Military Mobility Across Europe,” moderated by retired Lt. Gen. Ben Hodges, Pershing Chair in Strategic Studies, CEPA; speakers: retired Lt. Gen. Heinrich Brauss, former assistant secretary general for defense planning and policy at NATO; retired Brig. Gen. Hans Damen, strategic adviser for Insparcom; Tania Latici, policy analyst at the European Parliamentary Research Services; and Professor Dr. Julian Lindley-French, senior fellow at the Institute for Statecraft.

MAIN FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Military mobility has many moving parts: sending nations, transit nations, host nations, NATO, the EU, and potentially other international organizations outside Europe, as well as a host of civilian and military actors within nations. Effective coordination built on a deep understanding of the political, legal, and physical challenges is thus a vital first step to improving mobility. The five scenarios mentioned above highlighted a number of common challenges and requirements, and the working groups identified a series of findings and recommendations without which effective strategic and operational planning will be near impossible. These findings are discussed in Appendices 1 to 5.

The working groups’ findings and recommendations have been reviewed, consolidated, and are grouped in this section under the key functional areas that have been identified by the EU as central to enabling military mobility in Europe. These functions are also guiding discussions over the Structured Dialogue on Military Mobility between the EU and NATO at staff level: rules and regulations pertaining to the transport of dangerous goods, customs, and cross-border movement permissions, as well as transport infrastructure. A number of important crosscutting issues are also discussed in this section: command, control, and coordination relevant to military mobility, funding, special capabilities, resilience, and exercises. The aforementioned joint report by the European Commission and the high representative has also been analyzed and taken into account, and several senior experts from NATO and EU staffs have provided additional input on several specific topics central to the mission of the project.

Principal Considerations

There are several principal factors that should drive all efforts to improve the conditions for moving military forces to, across, and within Europe.

Engagement. The security environment is marked by the return of geopolitical great-power competition. As a consequence of China’s rapid rise to global power status, the United States is shifting its strategic center of gravity to the Indo-Pacific region. The United States’ European allies and partners will thus have to spend significantly more on deterrence and defense in Europe, as well as crisis management in North Africa and the Middle East. The November 2020 decision by the British government to increase its defense budget by 10% over four years could be a sign of an effort to address the coming challenge. Moreover, between 2016 and 2020 the European allies and Canada increased their accumulated defense expenditures by some $130 billion. Against such a strategic background, there is a clear common responsibility for both NATO and the EU to enable expeditious military mobility throughout Europe, which is why it has become both a flagship project for NATO-EU cooperation and central to transatlantic burden sharing. In short, establishing the foundational conditions required for military mobility and implementing them is both an urgent military requirement and a political necessity, and requires leadership awareness and engagement at the highest levels in NATO, the EU, and European capitals, at both political and military levels.

Planning. The five multinational civil and military project working groups have already greatly contributed to enhancing and raising awareness in capitals, EU institutions, and across NATO’s civilian and military staffs of the critical importance of military mobility for both the Alliance and the Union. Moreover, the discussions therein also addressed a number of issues important for comprehensive and effective military planning for the deployment of forces in a crisis, whether for enhancing deterrence and the collective defense of allies or crisis management beyond Europe. Critically, the responsible military headquarters and staffs of both NATO and the EU have long been engaged in military advance planning, including logistics planning, for deploying forces and sustaining them in theater. Credible deterrence can only be achieved when conditions are set for successful collective defense. Consequently, this report identifies the policies and actions needed to add value to their work. In the event of a crisis that requires the rapid movement of military forces across Europe, it would also require such forces to cross multiple national borders, pass across the territory of several nations in which different and differing national legislation applies, as well as use the available infrastructures of varying extent and quality. Military planning for the deployment of forces across Europe in peacetime, in a crisis, and war must, therefore, take into account national and EU legislation and regulations. Given the challenges, there is also a vital need to exercise and test coordination and standardization and deconflict processes prior to any emergency to ensure they function under duress and can thus meet planning timelines.

Whole-of-government approach. Even during a major crisis with Russia, the relevant peacetime legal regulations would still apply, for which the EU and various levels of national civilian and military authorities and actors are responsible and which differ from country to country. Therefore, for the enabling of rapid and effective military mobility a whole-of-government approach in all enabling nations is required. This would necessarily involve (inter alia) ministries of defense, interior, and transport, as well as private sector leaders responsible for air, rail, road, and port facilities. Therefore, the fostering of a whole-of-government military mobility culture through preestablished relationships will be particularly important in transit and host nations. Such a network of effect will demand established and robust relationships between national government and local authorities, those relevant industries responsible for the management of critical infrastructures, as well as those military commands responsible for coordinating and supporting the deployment of military forces and providing HNS and sustaining forces in theater. Ultimately, the test of effective military mobility will rest upon timely decision-making in an emerging crisis that is at the “speed of relevance” (in the words of former US Secretary of Defense James N. Mattis). While the EU clearly has a major role to play in promoting such political coherence, it is NATO that is and must be the driving force concerning requirements. A whole-of-government approach and effective NATO-EU cooperation on countering hybrid threats will be particularly important to successfully combat disinformation and promote enhanced cyber resilience.

Rules, Regulations, and Procedures

During a crisis, if the Alliance moves to deploy forces to reinforce allies and strengthen deterrence there would be no time for extensive political consultations and preparations of procedures for crossing borders and transiting countries ahead of a planned movement. Therefore, it is of utmost importance that all necessary data, arrangements, and forms are identified in advance, and developed, coordinated, and standardized between the nations, on the one hand, and between the EU and NATO on the other, as well as worked up through frequent exercises and improvements.

Streamline Cross-Border Movement Permissions. Smooth military movement requires harmonized procedures for requesting and issuing border-crossing and transit permission for all modes of transport. NATO has implemented a legal framework through Technical Arrangements (TAs) with both allies and those European partners that participate in the Partnership for Peace (PfP) program. These TAs are geared to NATO’s current advance planning. The EDA has also been working on two TAs within the framework of its program on “Optimizing Cross-Border Movement Permission Procedures in Europe” for military forces (military personnel, equipment, ammunition, fuel), one for the surface and another for the air domain. Twenty-five EU member states have joined the program, which is reportedly progressing well. The aim is to lift existing restrictions in national legislation. The TAs will thus facilitate the cross-border movement of EU member states’ forces and capabilities for operations, exercises, and daily activities and are expected to be completed and agreed by spring 2021. Therefore, it is essential that all EU member states commit to establishing a harmonized movement approval process within Europe. Norway has joined the program; it is important that other non-EU European allies join up as well or at least establish compatible rules.

Standardize regulations for the transport of dangerous goods. Effective military mobility also requires harmonization of EU member states’ legislative frameworks and diverging national approaches to authorizing the movement of dangerous goods. Several EU bodies (the EDA, the European Commission, and the European External Action Service) have been working, including within the scope of the TAs for the surface and the air domains, to enable harmonization of respective practices across EU member states. The combining of civilian rules with, where necessary, the provisions of the NATO Standardization Agreement, AMovP6, as the reference set of rules for the transport of dangerous goods in the military domain, is considered sufficient by the EU to allow for the speedy international transport of dangerous goods for military purposes (in accordance with the October 2020 joint report by the European Commission and the high representative of the EU). The legal basis for the transport of dangerous goods should, therefore, be determined by the EU member states as soon as possible. A harmonized legal basis is particularly important for both transit nations and host nations. The aim should be to achieve annual renewal/update of approval for the transport of a range of dangerous goods along defined multimodal movement corridors.

Promote standardized customs procedures. All European governments should apply streamlined customs procedures for military transport throughout Europe. Based on the PfP Status of Force Agreement (SOFA), allies and PfP partners use NATO Form 302 for exemption from customs related to the movement of goods for use by a deploying force. For its part, the EU has recently developed, in full transparency and dialogue with NATO, EU Form 302 which is to be used alongside the existing NATO Form 302. Together, these forms enable rapid customs declarations for various military cross-border movements, including within the framework of the EU CSDP (through EU Form 302). While NATO Form 302 is already digitalized, the EDA is working on a digitalized format of its Form 302, which is supposed to be available in 2024. Although these forms are designed to ensure uniform treatment of all cross-border military movements by customs in all EU member states and non-EU allied countries, there is a concern about duplication of effort and data ownership. Moreover, every custom officer in every European country must be aware of, trained, and thus able to correctly apply the pertinent procedure. Therefore, in order to simplify the customs process for all military movements in Europe, the EU and NATO should make an effort to jointly develop identical 302 templates, while retaining their distinct legal basis.