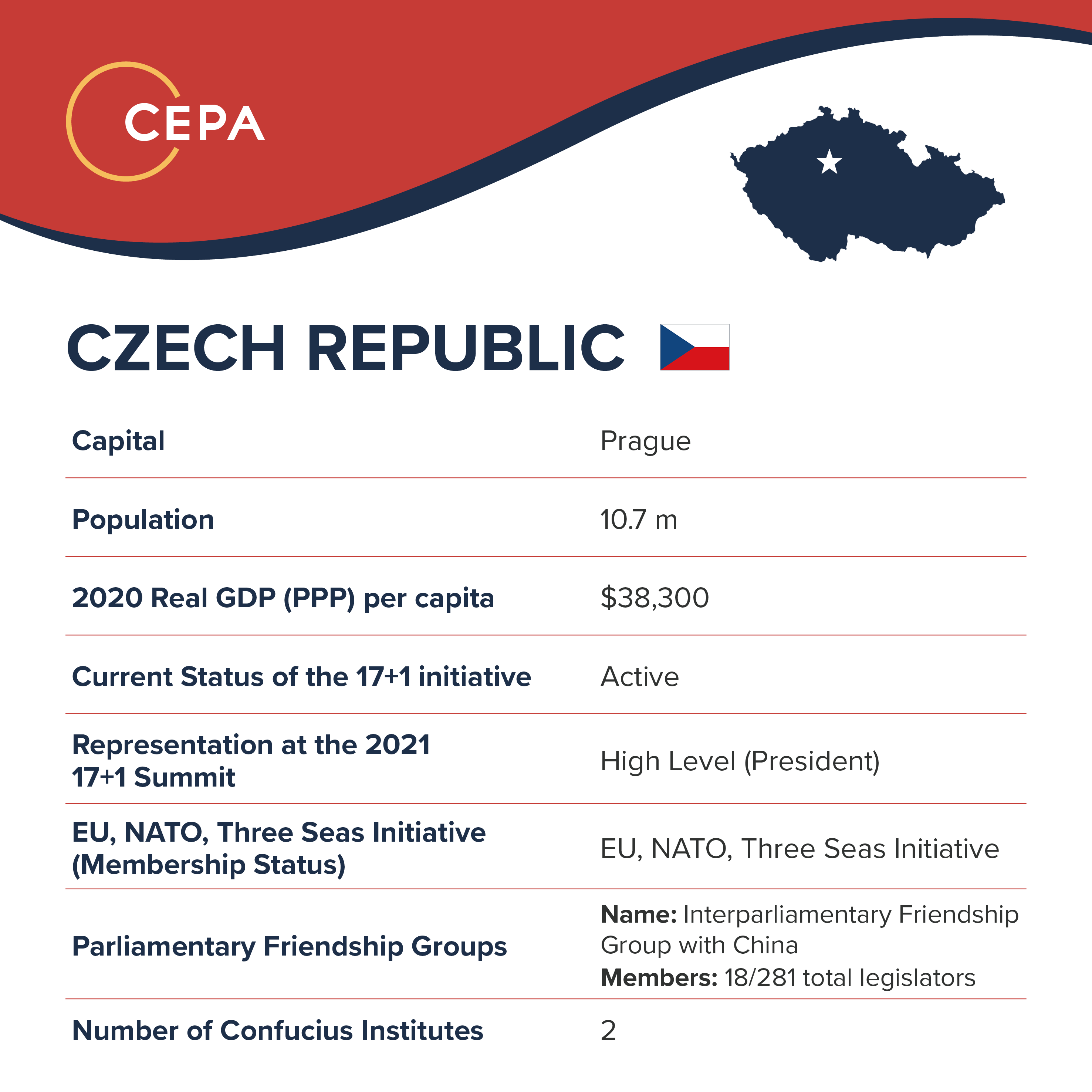

This report is a part of #CCPinCEE, a series of reports published by the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA) analyzing Chinese influence efforts and operations across the nations of Central and Eastern Europe.

Goals and objectives of CCP malign influence

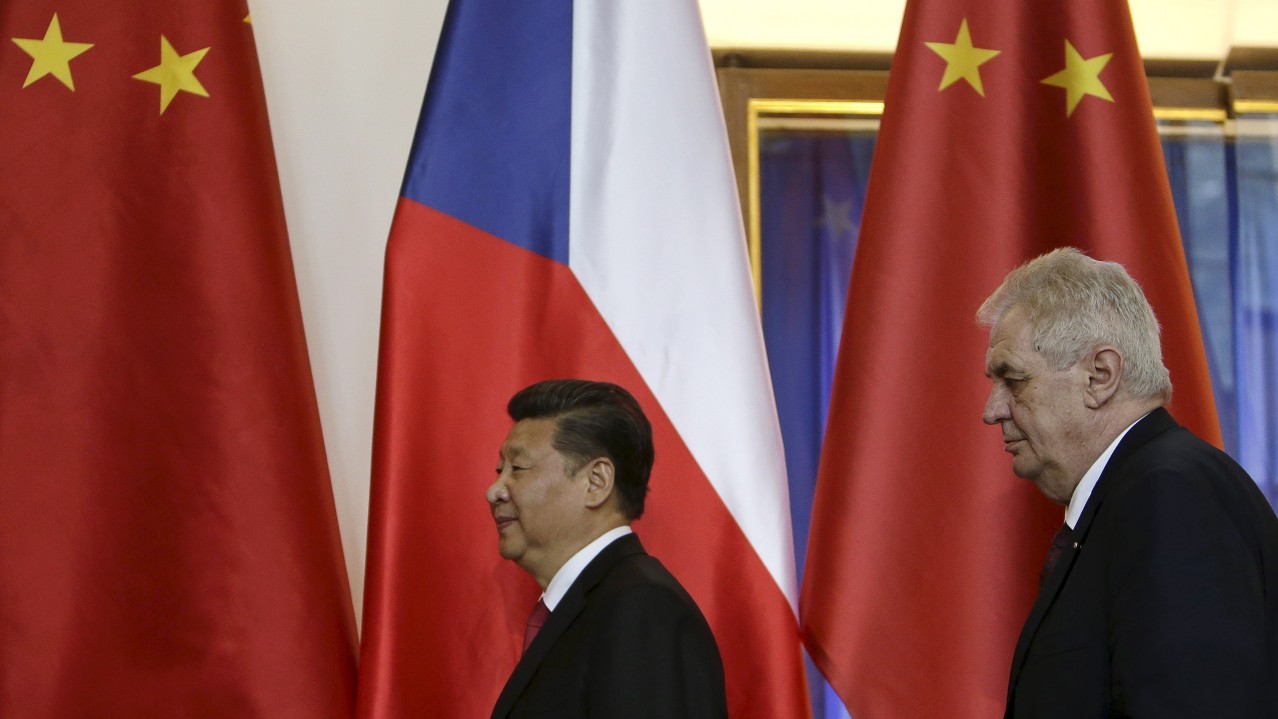

China, as a set of issues and dilemmas, is a relative newcomer to the Czech policy sphere, with the two countries engaging substantially only after the establishment of the 16/17+1 format in 2012. Their relations, frozen for years due to Czech criticism of human rights abuses in China and the Dalai Lama’s frequent visits to Prague, underwent a dramatic thaw. The new Social Democratic government, supported by President Miloš Zeman, announced a “restart” of its relations with China in 2013-2014.

Unlike the Russian Federation, China could not draw on previously established links or knowledge of the local political and economic environment. But China has been on a steady learning curve, using a variety of tools, ranging from benign to more dangerous.

Beijing’s main strategic goals have been to weaken political support in the Czech Republic for sovereignty for Taiwan and Tibet and for other countries’ territorial claims in the South China Sea, issues the Chinese government considers its core interests, and to improve China’s image in the country, for example by fighting narratives depicting it as a human rights violator and the source of the COVID-19 pandemic. By shifting the Czech Republic’s policies and actions on these issues, China also aims to influence key international organizations, such as the EU and NATO, of which the Czech Republic is a member. Beijing uses a wide range of methods in the Czech Republic, from public diplomacy to less benign and more covert efforts, as its target audience gets ever wider, from the national government, to regional and municipal governments, to political parties, to economic elites and intellectuals, and ultimately to society at large.

China uses a combination of inducements and punishments.1 Carrots include attempts to cultivate political and economic elites through increased diplomatic exchanges, high-level visits, (co-)sponsored trips for politicians, investments, and increased party-to-party relations. China also dangles the promise of economic benefits from political cooperation with China — such as offers to establish direct transport links, increase investment, and bring more Chinese tourists to the country — to woo Czech political and business leaders. In addition to top-level contacts, Beijing encourages China’s local governments to reach out to their Czech counterparts.

Perhaps the types of malign influence most dangerous to democratic society are China’s efforts to mold Czech public opinion, including by establishing Confucius Institutes and Confucius Classrooms. Its success here has been mixed. When Prague University of Economics and Business and other public universities in Prague rejected offers to host a Confucius Institute,2 the regional Palacký University in Olomouc3 said yes. In Prague, China has managed to open a Confucius Institute only at the private University of Finance and Administration in 2018.4 That laid a foundation for further academic influence, but without the prestige of cooperation with Charles University that Beijing had originally sought. On the other hand, in 2015, a Czech-China research center opened at Charles University, with some co-funding from the Chinese Embassy, only to close amid scandal in late 2019.5 Its activities included an annual conference highlighting the Chinese government’s positions on security, development, and other issues. Some students said a course on Chinese affairs was biased in China’s favor, and researchers chose students to travel on embassy-funded trips to China.6

The last type of notable Chinese malign influence entails spreading pro-China narratives through mainstream and alternative media7 and social media.8

Chinese malign influence made some headway in the early years after China’s entry into the region in 2012. Since then, China has lost its luster in the Czech Republic for several reasons: civil society groups have launched research and publicity campaigns about the perils of Beijing’s influence, reinforced by separate investigative reporting; anticipated Chinese investment in the country has not materialized; opposition parties have used criticism of China as a weapon against the government and president for their closeness to Beijing; and EU officials’ increasing wariness of cooperation with China has increased the political and reputational risks for Czech actors.

CCP’s methods, tools, and tactics for advancing malign influence

For the first several years after the “restart” of relations in 2013, China was able to move largely unseen, its cause championed by various local intermediaries, including former high-ranking officials,9 even one who retained a high-level security clearance despite having previously worked for CEFC, a dubious Chinese energy conglomerate, for two years.10 Other proxies included companies with a large stake in the Chinese market; think tanks, including some secretly funded by companies doing business in China1112 ; and potentially even journalists.13

China has also systematically cultivated young politicians, scholars, and journalists through programs that draw in figures across the ideological spectrum and introduce them to their counterparts in the Chinese Communist Party or related organizations, such as the Bridge for the Future or China-CEE Young Political Leaders Forum, with the involvement of the All China Youth Federation.1 These programs are opaque and go largely unnoticed in the Czech Republic. Czech intelligence has warned that Czech politicians’ trips to China leave them open to Chinese government influence through the genuine positive impact of the trip, or even blackmail based on information gathered through intelligence operations.14

When carrots fall short, China is ready with sticks,1 including shunning state representatives,15 canceling visits, renouncing agreements,16 canceling direct lines,17 refusing to send pandas,18 threatening economic problems for companies operating in China,19 limiting tourism, canceling cultural events,20 staging demonstrations organized by the Chinese “public,”21 and threatening divestment,22 among other punishments.

Sources: The World Factbook 2022, (Washington, DC: Central Intelligence Agency, 2020), https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/; World Bank, The World Bank Group, 2022, https://www.worldbank.org/en/home; “Members – Czech republic – China”, Chamber of Deputies Parliament of The Czech Republic, Retrieved June 27, 2022, https://www.psp.cz/en/sqw/snem.sqw?l=en&id=1692

Reach of CCP tactics

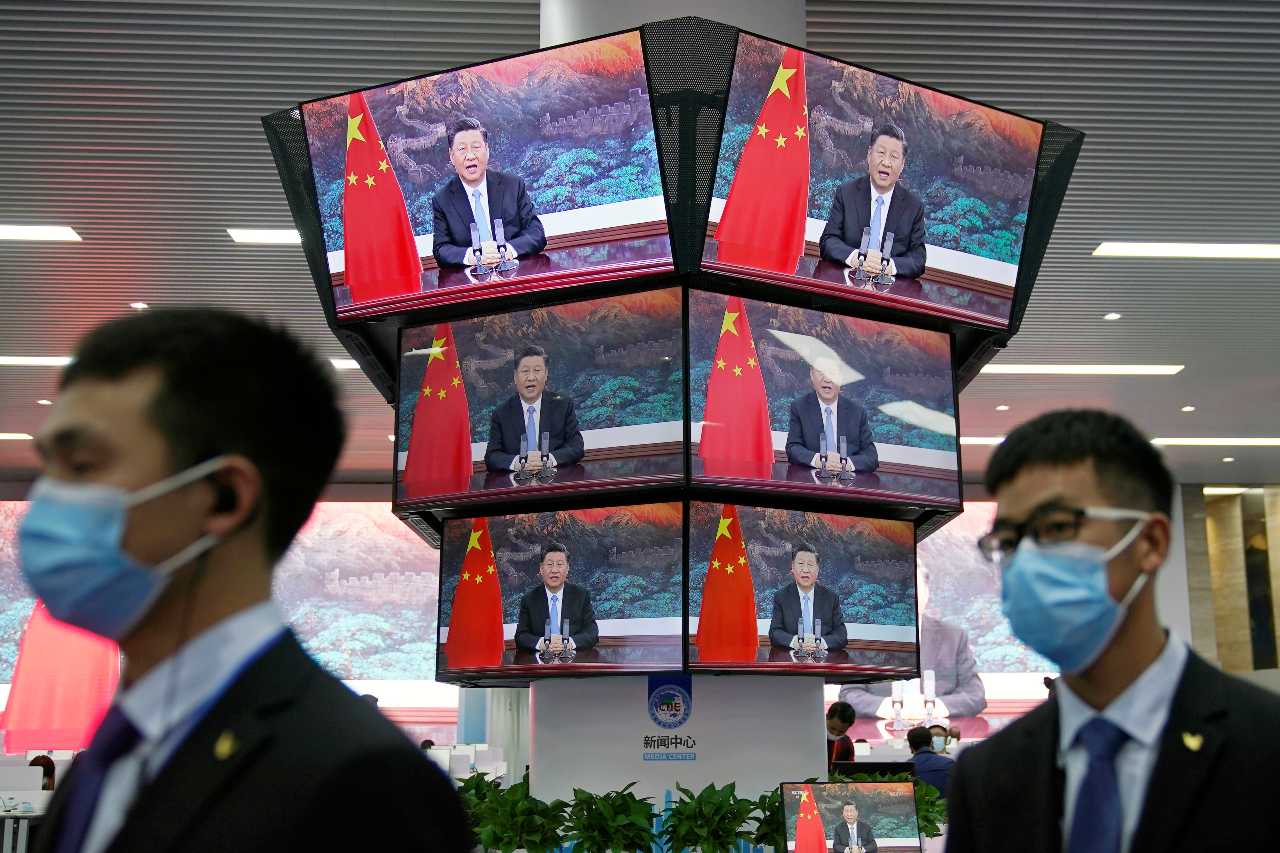

There is ample evidence of China’s attempts to manipulate public discourse and media behavior in the Czech Republic, helped along by media consolidation. Chinese officials write op-eds, pay for supplements in print media, and attempt to shape public discourse with propaganda and disinformation.

For example, when CEFC invested in the Czech media company Empresa Media, coverage of China in the major, Empresa-owned, Tyden magazine went from balanced to wholly positive. Another Empresa property, TV Barrandov, famous for weekly interviews with Czech President Miloš Zeman, started to cover the Belt and Road Initiative more frequently than any other Czech media.23

Apart from broadcasts in English, German, Italian, French, Portuguese, and Spanish, the state-owned China Radio International broadcasts and runs internet sites in seven other EU countries’ languages: Bulgarian, Croatian, Czech, Greek, Hungarian, Polish, and Romanian. While CRI’s coverage area is limited and its appeal to the CEE audience is debatable, it could help influence the local public, including the diaspora of second and third generations of ethnic Chinese.

The Czech Republic has been targeted by propaganda on the origin of the coronavirus, spread mostly through alternative and fringe media and Chinese outlets, such as CRI. MapInfluenCE research found that apart from highlighting the alleged achievements of “mask diplomacy,” Chinese social media accounts in the Czech Republic have attacked the US, including with reposts of disinformation narratives on COVID-19 originating in the US. However, this content was not customized for the local audience, which points to a rather passive reposting of content created elsewhere.24

Finally, China has slowly built up a presence on social media platforms in the Czech Republic, a trend that accelerated in 2019-2020. The Chinese Embassy in Prague established its Facebook page in 2015 and opened a Twitter account in February 2020, following the trend of other Chinese embassies around the world. Both channels became especially active during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Photo: The first freight train X8074 of China Railway Express running from Prague to Yiwu is pictured after arriving at the Yiwu West Station in Yiwu city, east China’s Zhejiang province, 4 August 2017. Credit: Oriental Image via Reuters Connect

Target audiences and populations

As with any case of external malign influence, China’s efforts exploit existing divisions in society. In the Czech Republic, that has meant targeting those generally dissatisfied with the country’s direction and relying on both latent and open euroskepticism and anti-Western sentiment. China’s influence is largely exercised through Czech proxies whose own interests coincide with China’s efforts to burnish its image and align with China’s specific diplomatic causes. For example, Zeman publicly touts promises of Chinese investment or threats of divestment.22 And in 2020, the Czech president’s office asked the Chinese Embassy in Prague to threaten the senate president,25 Jaroslav Kubera, with retaliation if he followed through on a planned visit to Taiwan. Kubera died before he could take the trip.26

Conclusion

While Chinese malign influence operations enjoyed significant success in the early years after China’s entry to the region, developments in recent years signal a return to a more China-skeptical position among Czech society.

- Ivana Karásková et el., “China’s Sticks and Carrots in Central Europe: The Logic and Power of Chinese Influence,” Association for International Affairs (AMO), June 2020, https://mapinfluence.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Chinas-Sticks-and-Carrots-in-Central-Europe_policy-paper_-1.pdf. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Jakub Zelenka, “Číňané chtěli otevřít institut na VŠE i Univerzitě Karlově, tam je odmítli. O politiku nemáme zájem, říká Zima,” Deník N, November 15, 2019, https://denikn.cz/234318/cinsky-konfuciuv-institut-odmitla-vse-i-univerzita-karlova-nejde-jen-o-jazyk-a-kulturu-vadilo-zimovi/. [↩]

- “Konfuciův institut,” Palacký University, https://konfucius.upol.cz. [↩]

- “Na Vysoké škole finanční a správní bude čínský Konfuciův institut. Kvůli špionáži před ním varuje FBI,” CTK, November 19, 2019, https://domaci.hn.cz/c1-66678330-na-vsfs-bude-konfuciuv-institut-jine-vysoke-skoly-odmitly-ma-jit-o-castecne-politicky-zamereny-institut. [↩]

- Lukáš Valášek, Jan Horák, “Konference, které pořádá rektor UK Zima, platila skrytě statisíci čínská ambasáda,” Aktuálně, October 25, 2019, https://zpravy.aktualne.cz/domaci/konferenci-uk-platila-cina-stredisko-bezpecnostni-politiky/r~79c2b80ef4b311e9858fac1f6b220ee8/.; Alžběta Bajerová, “The Czech-Chinese Centre of Influence: How Chinese Embassy in Prague Secretly Funded Activities at the top Czech University.” China Observers in Central and Eastern Europe (CHOICE), November 7, 2019. [↩]

- Andrea Procházková a Lukáš Valášek, “Za odměnu s Univerzitou Karlovou zdarma do Číny,” Respekt, October 29, 2019, https://www.respekt.cz/politika/za-odmenu-s-karlovou-univerzitou-zdarma-do-ciny. [↩]

- See e.g. Ivana Karásková, “How China influences media in Central and Eastern Europe,” The Diplomat, November 19, 2019, https://thediplomat.com/2019/11/how-china-influences-media-in-central-and-eastern-europe/; Ivana Karásková, “China’s Evolving Approach to Media Influence: The Case of Czechia,” The Diplomat, November 13, 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2020/11/chinas-evolving-approach-to-media-influence-the-case-of-czechia/. [↩]

- Ivana Karásková, “One China under media heaven: How Beijing hones its skills in information operations,” Hybrid CoE Strategic Analysis 23. Helsinki, Finland, The European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats, 2020, https://www.hybridcoe.fi/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/20200625_Strategic-Analysis_23_China_Web.pdf; Ivana Karásková et al., “China’s propaganda and disinformation campaigns in Central Europe,” Association for International Affairs (AMO), August 2020, https://mapinfluence.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Mapinfluence_BRIEFING-PAPER_chinas-propaganda_A4_interaktivni_EN_01-1.pdf. [↩]

- Ivana Karásková, Tamás Matura, Richard Q. Turcsányi, Matej Šimalčík, “Central Europe for Sale: The Politics of China’s Influence,” Policy paper, Association for International Affairs (AMO), April 16, 2018, http://www.chinfluence.eu/central-europe-for-sale-the-politics-of-chinas-influence-2/. [↩]

- Lukáš Prchal, Jakub Zelenka, “Hamáčkův náměstek může být bezpečnostní riziko, varuje část expertů. Pracoval pro CEFC, která je vnímána jako součást infiltrace Číny do politiky,” HN, August 9, 2018, https://archiv.hn.cz/c1-66211370-hamackuv-namestek-muze-byt-bezpecnostnim-rizikem-firmy-typu-cefc-pro-kterou-pracoval-jsou-casto-vnimany-jako-infiltrace-ciny-do-politiky-zemi. [↩]

- Jan Horák, Lukáš Valášek, “Home Credit přiznal podporu pročínského webu Sinoskop. Je objektivní, vysvětluje,” Aktuálně, December 10, 2019, https://zpravy.aktualne.cz/domaci/home-credit-priznal-podporu-procinskeho-webu-sinoskop-je-obj/r~7d0b3b781b4e11ea858fac1f6b220ee8/. [↩]

- Šárka Pálková, “Chteli jsme racionalizovat diskusi o Cine, vysvetluje Home Credit najmuti PR agentura“ December 14, 2019, https://zpravy.aktualne.cz/domaci/chteli-jsme-racionalizovat-diskuzi-o-cine-vysvetluje-home-cr/r~404173d21e6011ea8d520cc47ab5f122/. [↩]

- Zuzana Kubátová, “Kellner je o krok blíž TV Nova, vyhráno ale nemá,” Seznam Zprávy, February 27, 2020, https://www.seznamzpravy.cz/clanek/kellner-je-o-krok-bliz-tv-nova-vyhrano-ale-nema-90408; Ondřej Neumann, “Petr Kellner a média. Miliardář na špatné adrese”, Hlídací pes, July, 12, 2021, https://hlidacipes.org/ondrej-neumann-petr-kellner-a-media-miliardar-na-spatne-adrese/. [↩]

- “Výroční zpráva Bezpečnostní informační služby za rok 2013,” BIS, 2014, https://www.bis.cz/public/site/bis.cz/content/vyrocni-zpravy/2013-vz-cz.pdf. [↩]

- Jakub Zelenka, “Šikana, zastrašování a trestání. Diplomaté popisují, jak se Čína chová k Česku,” Deník N, September 12, 2019, https://denikn.cz/195533/sikana-zastrasovani-a-trestani-diplomate-popisuji-jak-se-cina-chova-k-cesku/. [↩]

- Alžběta Bajerová, “Inside of China’s Current Hassle with the ‘Rogue’ Mayor of Prague,” China Observers in Central and Eastern Europe (CHOICE), August 1, 2019, https://chinaobservers.eu/inside-of-chinas-current-hassle-with-the-rogue-mayor-of-prague/. [↩]

- Tomáš Klézl, “Z Prahy do Pekingu už jen s přestupem. Čína zrušila jedinou přímou linku mezi městy,” Aktuálně, January 22, 2020, https://zpravy.aktualne.cz/domaci/z-prahy-do-pekingu-uz-jen-s-prestupem-cina-zrusila-linku/r~e2b9fcda3d1711ea9b40ac1f6b220ee8/; Ondřej Kundra, Tomáš Brolín, “Čína zatrhla přímou leteckou linku z Pekingu do Prahy,” Respekt, January 22, 2020, https://www.respekt.cz/politika/cina-zatrhla-primou-leteckou-linku-z-pekingu-do-prahy. [↩]

- Robert Oppelt, “Medvídek, který nikdy nepřiletí. Praha o pandy usilovala marně,” iDNES, December 1, 2018, https://www.idnes.cz/zpravy/domaci/panda-cina-zoo-praha-milos-zeman-miroslav-bobek-pandi-diplomacie.A181130_205831_domaci_mpl. [↩]

- “Potrestáme vás i české firmy. Čína prostřednictvím Hradu nepokrytě vyhrožovala Kuberovi,” CTK, February 19, 2020, https://www.novinky.cz/domaci/clanek/cina-poslala-na-hrad-dopis-kde-varovala-pred-nasledky-kuberovy-navstevy-tchaj-wanu-40313959. [↩]

- Brian Kenety, “Czech Culture Minister: China’s cancellation of concert tours damages relations,” Radio Prague International, September 9, 2019, https://www.radio.cz/en/section/news/czech-culture-minister-chinas-cancellation-of-concert-tours-damages-relations. [↩]

- Ivana Karásková, “Hijacking the Czech Republic’s China policy,” ChinfluenCE, October 27, 2016, https://www.chinfluence.eu/hijacking-czech-republics-china-policy-3/. [↩]

- “Kvůli Hřibovi přestane Čína financovat fotbalovou Slavii a letadla odkloní do Chorvatska, tvrdí Zeman,” iHNED, Octiober 10, 2019, https://domaci.ihned.cz/c1-66657790-cina-podle-zemana-prestane-financovat-fotbalovou-slavii-reaguje-tak-na-vypovezeni-sesterske-smlouvy-s-prahou. [↩] [↩]

- Ivana Karásková et al., “Central Europe for Sale: The Politics of China’s Influence,” Association for International Affairs (AMO), 2018, http://www.chinfluence.eu/central-europe-for-sale-the-politics-of-chinas-influence-2/. [↩]

- Ivana Karásková et al., “China’s propaganda and disinformation campaigns in Central Europe,” Association for International Affairs (AMO), August 2020, https://mapinfluence.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Mapinfluence_BRIEFING-PAPER_chinas-propaganda_A4_interaktivni_EN_01-1.pdf. [↩]

- “Potrestáme vás i české firmy. Čína prostřednictvím Hradu nepokrytě vyhrožovala Kuberovi,” novinky.cz, February, 19, 2020, https://www.novinky.cz/domaci/clanek/cina-poslala-na-hrad-dopis-kde-varovala-pred-nasledky-kuberovy-navstevy-tchaj-wanu-40313959. [↩]

- Jakub Zelenka, Lukáš Prchal, “Jak vznikl výhružný dopis Kuberovi: U čínské ambasády ho objednal hradní kancléř Mynář,” Deník N, March 30, 2020, https://denikn.cz/329631/jak-vznikl-vyhruzny-dopis-kuberovi-u-cinske-ambasady-ho-objednal-hradni-kancler-mynar/. [↩]