As the world watches with trepidation the deployment of more Russian troops to the border of Ukraine, Russian biggest companies and banks are looking with equal trepidation at their own tech departments.

The US has made it known the new sanctions would affect the imports of technology into Russia, and they are expected to hit hard.

On the surface, Russia is well-prepared for this kind of sanction: the Kremlin has for years pushed for import substitution of Western technologies, introducing since 2015 all kinds of incentives and punishments for state-owned corporations and government agencies to induce them to move to the Russian-made software and hardware.

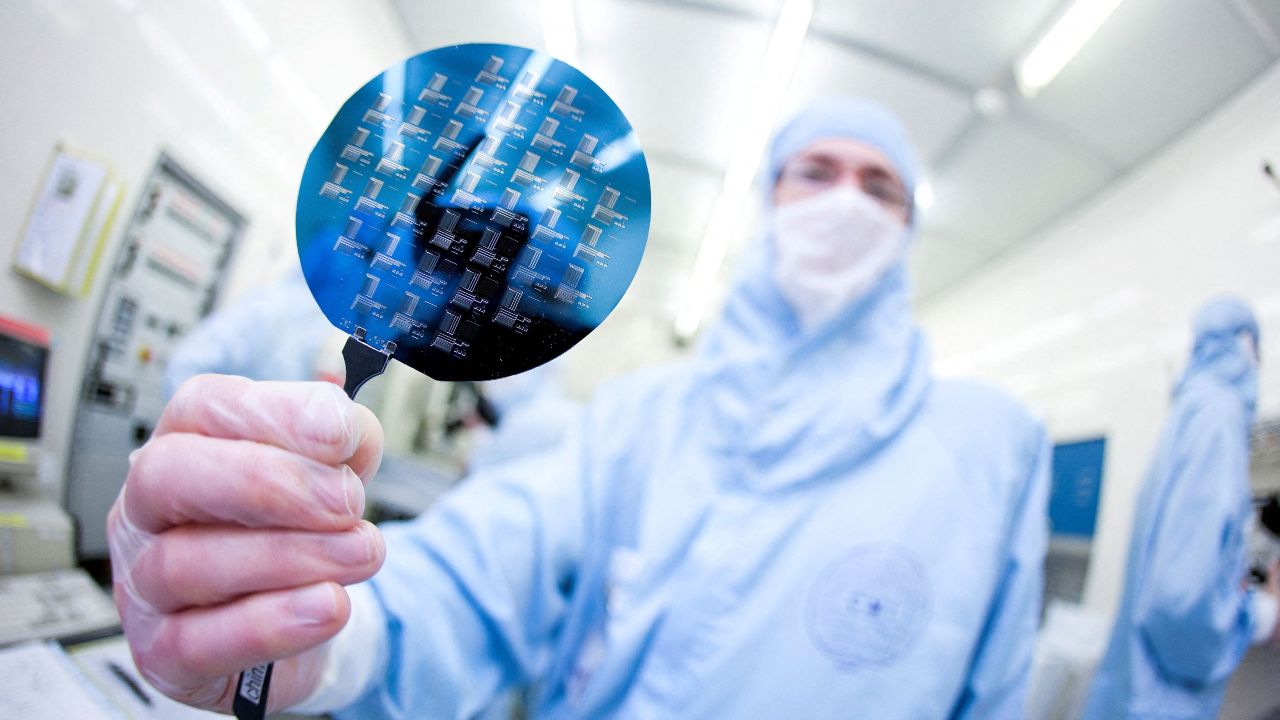

There have been some results — government agencies and state-controlled corporations are lining up right now to test hardware solutions based on Baikal-M microprocessors, which are Russian-made and developed.

But at the very same time Sber, the largest state bank in Russia, ran technical exercises imitating the effects of the expanded Western sanctions, modeling what happens if the bank’s tech infrastructure gets cut off from software and hardware support from giants like Microsoft, Oracle, Intel, and SAP.

The results were apparently so mixed that Sber decided to acquire huge quantities of Western-made equipment, servers, data storage hardware, software, when they are still available, before the sanctions hit. Sber is wasting no time: it is already known the bank allocated $31.8m just for Vmware products, an industrial cloud software provider.

Sber is not just the largest Russian bank. It is led by the visionary Herman Gref, one of Vladimir Putin’s closest allies. Gref is a Kremlin intimate who believes that digitalization could fix things that traditional Russian bureaucracy fails to deal with, and he has been using all his weight to make Russian digitalization happen, including the 2018 establishment of a cyber and AI training school. Gref turned Sber into a testing ground for all kinds of online solutions, and if he is making a strategic decision to purchase the tech abroad while it’s still available, others will be following his approach.

And he is not the only one who is skeptical about Russian software and hardware. Many big corporations openly voiced their concern that Russian computers are insufficiently reliable to be used in big industrial solutions.

So, what is the biggest Russian tech problem?

The bottleneck is scale: Russian-made software and hardware are good when used in small- and medium-sized companies, but when it comes to big companies, meaning huge amounts of traffic and data, problems arise. Hardware, its reliability, and compatibility with software is one challenge; database management systems, for instance, is another.

Larry Ellison, a founder of Oracle, once famously said: “The only way the ORACLE will ever be delivered to Russia is in the nuclear warhead of an ICBM.” The remark was made at the height of the Cold War, when Cocom exports controls were still in place.

Things changed from the 1990s, with Oracle gradually becoming omnipresent in Russian corporations and government agencies. Nowadays Oracle can be found almost everywhere, even Russia’s secret police force, the FSB. And it is hard to find replacements. The solution the Russian authorities came up with is a compromise: the Russian Digital Development Ministry has promoted PostgreSQL as a replacement of Oracle, even though PostgreSQL was also developed in the US, at the University of California. Russia’s authorities believe that since it is freeware, it would be immune to the sanctions. (It is worth noting that not one of the tech companies mentioned so far in this piece is Chinese.)

Few people doubt that Russia is a country full of excellent engineers, and with time, will overcome the obstacle of scale. But the crucial word here is time.

Russia’s heavily regulated tech industry abides these days by the government’s established quotas for gradual import substitution for state companies and state organizations: in 2021 the percentage of Russian-made equipment was established at 50% (not all companies complied even under immense government pressure), this year the ambition is to reach 60% and next year 70%.

But even this scenario makes clear that with current Western sanctions, the government-controlled sector would be left high and dry for at least 40% of their tech needs.

It is a huge gap. Even if Chinese firms got the green light, Chinese companies would not be able to fill it quickly. There are many factors Putin must consider before launching another invasion of Ukraine: this is very certainly one of them.

Andrei Soldatov and Irina Borogan are nonresident senior fellows with the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA.) They are Russian investigative journalists, and co-founders of Agentura.ru, a watchdog of Russian secret service activities.