Once upon a time, the West was almost the sole source of aid to poorer countries. Not any longer. Assistance to developing and emerging countries has now become much more politicized and competitive, a phenomenon illustrated by the rush by Russia and China to fly desperately needed vaccines to needy recipients.

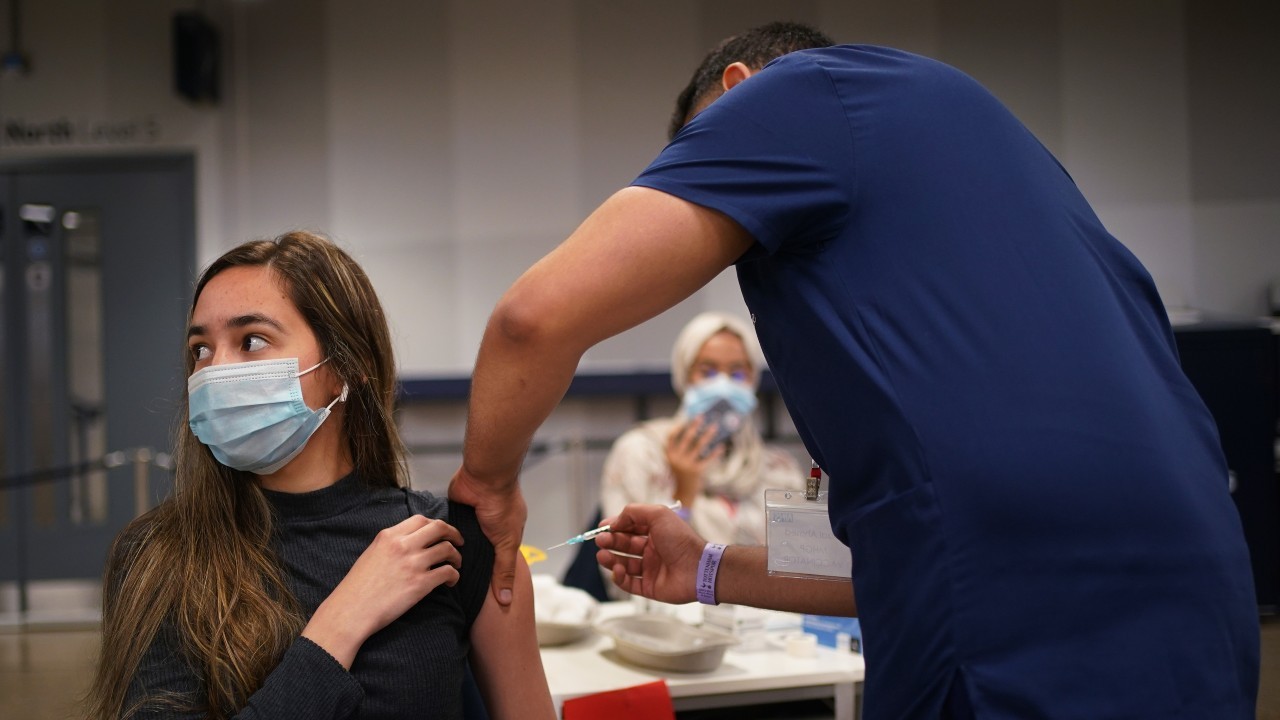

The Western response has been slow. Understandably, Western states have prioritized their own citizens with an armory of highly effective vaccines. But with the most vulnerable groups now vaccinated in many North American and European countries, there is a new willingness to step up assistance elsewhere.

Last week, the outline of this response was announced at the G7 meeting in Cornwall and the EU-U.S. summit, where leaders representing 780 million people offered to provide a billion vaccine doses over the next year. But while France, Germany, and Italy joined their G7 counterparts in making the commitment to poorer nations, World Health Organization Secretary-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus emphasized that “more than 10,000 people are dying every day . . . these communities need vaccines, and they need them now, not next year.”

That is underlined by the statistics: More people have died of covid-19 in 2021 than in all of 2020. Western states might reasonably point out that their pledges now greatly exceed those of Russia and China with the U.S. alone contributing 500m doses and 100m apiece from the EU and the UK (and EU-based vaccine manufacturers have pledged to donate 1.3bn doses.) Unfortunately, this is still catastrophically low: The WHO says the world needs 11bn doses by the time of next year’s G7 summit in Germany.

Seeking to fill the gap, Russia and China have rushed to offer supplies, even though Russia has struggled to vaccinate its population and the pace of China’s vaccine drive only recently accelerated, while questions about the efficacy of its vaccines persist. Even so, these vaccines, though still not approved by the EU or the U.S., have been welcomed with open arms by governments across the developing world. Even in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), where memories of past Russian behavior linger, EU member states and EU hopefuls have accepted Russian and Chinese vaccines with increasing enthusiasm. The grim lesson of the pandemic has been that reliance on the EU and the vaccine delivery alliance, COVAX — which includes WHO and the UN Children’s Fund, UNICEF — did not deliver.

This failure played into the hands of the world’s two largest autocratic powers, neither of which has a record for open-handed generosity toward the poor. But their campaigns were certainly not pre-ordained for success: European public opinion on China has soured since 2018, and attitudes toward Russia were already negative. Yet with little help arriving from the EU during 2020 or early 2021, there were few alternatives, especially among the hardest-hit and poorest nations. Within the EU itself, Hungary and Slovakia have emerged as eager partners for Russia and China’s vaccine diplomacy. Hungary has purchased around 7m doses of the Sputnik V and Sinopharm vaccinations, achieving one of the highest vaccination rates in Europe as a result. In Slovakia, even after irregularities were detected in a shipment of 200,000 Sputnik V doses, the vaccine nonetheless was approved by regulators and remains a popular option.

Further south in Serbia, a nation which purchased around 6m doses of the Sinopharm and Sputnik V inoculations, “China [and Russia] . . . once again seized the opening left by the EU’s slow strategic reflexes, and it scored big in the country,” according to Vuk Vuksanovic in a CEPA article in February. To highlight the political nature of vaccine diplomacy, Serbian Prime Minister Aleksandar Vučić even chose inoculation with China’s Sinopharm vaccination, despite the availability of Western options.

Serbia has used this supply to engage in vaccine diplomacy of its own, by gifting non-Western vaccines to its poorer neighbors, including 40,000 doses for North Macedonia alone.

It is worth noting that historical realities mean that strategies effective in one country may not work in another — opinion polls show Poles and Czechs strongly resistant to Russian and Chinese vaccines compared with Slovaks and Hungarians.

Now at least, Europe has a story to tell. The EU has set about fixing the issue, and this fresh start will require a parallel policy to improve its public relations, in coordination with the U.S., to counter Russian and Chinese information operations. These have not only trumpeted the qualities of the autocratic vaccines, they have also aimed to erode confidence in generally better Western alternatives.

One element of any European information effort will no doubt point out that while foreigners may be willing to accept the Sputnik V vaccine, huge numbers of Russians are not. There is a price to devaluing truth, and that is being paid by the Russian people. Only around 20m Russians from a population of some 146m have received at least one dose, although it has been free and on offer since December.

To further illustrate Russia and China’s intentions, Western bodies can also emphasize that at the outset of the pandemic Russia and China claimed to have donated medical supplies, when they in fact convinced desperate countries to buy often faulty equipment.

The West’s vaccine diplomacy is already starting to work. Soon, desperate nations will not have to accept political strings and trade-offs from Russia and China in return for life-saving vaccines. That is something to welcome.