The first part of the long-awaited Summit for Democracy takes place from December 9-10. While China and Russia expressed their disappointment at their exclusion by publishing a comical op-ed, the piece was little more than trolling: no one expected the authoritarian regimes expressing longstanding hostility to the rules-based order to be involved. However, the Hungarian reaction — blocking joint participation by the European Union (EU) — was much more problematic and revealed an important problem in the heart of the Biden administration strategy to support “democratic renewal.”

Hungary is the only one of 27 EU states not to be invited, a very clear signal from the Biden administration of its disapproval at what the US view of democratic backsliding And yet, while Hungary and Turkey were excluded from the list of invitees, states with an arguably more checkered record, like Armenia, Iraq, Pakistan, the Philippines and India were all asked by the White House. This reveals at least two things. Firstly, the summit is not openly geopolitical. Secondly, that prospects and differing starting points were probably considered when drafting the list.

In principle, this is positive. Good governance and democratic institutions are not synonymous with geopolitical alignment to major Western powers. Past realpolitik in dealings with convenient authoritarians while actively pursuing a policy to promote democracy is still exploited by Chinese, Russian, and Iranian propagandists against the US and her allies. The Summit for Democracy and the emerging anti-kleptocratic consensus in the US can help counter such arguments in the future.

By the end of this week, it should be possible to reach a shared understanding and draft resolutions about what will be done. In the meantime, it is worth remembering that the West is busily sharpening its economic weaponry to target individual and nation-state miscreants — the White House published its anti-corruption strategy on Monday (including interesting ideas like a kleptocracy asset recovery rewards program), while the EU is preparing new sanctions tools with a potentially dramatic impact on its global role.

This underlines that the struggle for democracy in 2021 is less geopolitical than the “first” Cold War. And that the recognition of the damage done by corruption and kleptocracies also requires an unprecedented level of Western self-criticism; since all too often it is Western banks and elites that are recipients of illicit wealth.

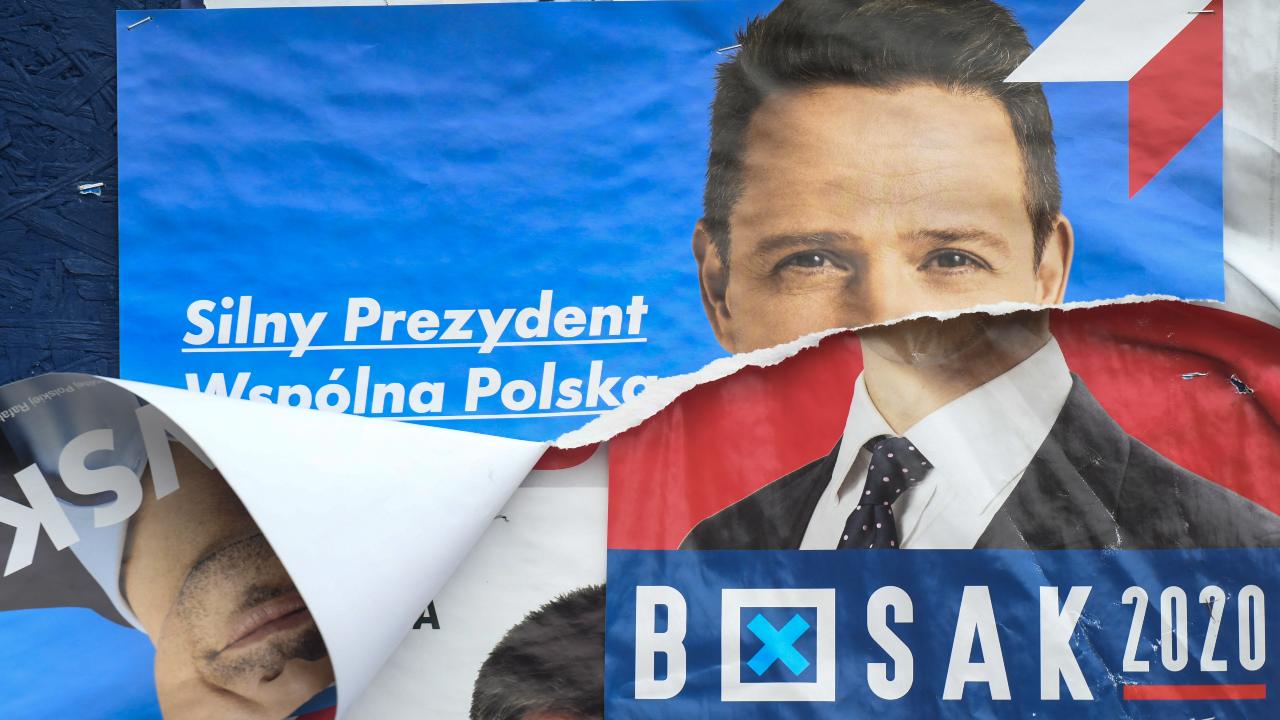

Democracy is also challenged by authoritarian figures from within. Part of the problem behind this rise of authoritarianism is undoubtedly the failure of politics to adequately address post-Cold War crony capitalism. Warnings from Fiona Hill and Robert Kagan should not be ignored. Similar challenges can be seen all over the European continent and in democratic Asia, too.

Despite the advances of the corrupt, the counter-campaign gathers strength through a web of common regulations, standards, reforms, and sanction policies at national and international levels.

This is where geopolitics comes back to the picture.

China, Russia, Iran, and many other less significant authoritarian states use corruption as a tool of foreign policy. For Russia in particular, it has been a repeated pattern to threaten military action when other means have failed. After Ukraine sanctioned Viktor Medvedchuk — one of its citizens, a close Putin ally, and a key figure for Russian influence — the Kremlin’s rage was visible in the form of a dramatically increased Russian military presence. When Cyprus signed a memorandum of understanding with the US on issues including money laundering in 2018, the Russian Foreign Ministry spokesperson Maria Zakharova (tellingly but truthlessly) presented the issue as a “military buildup”

And yet, in the age of hybrid warfare, it makes sense to acknowledge the Clausewitzian recognition of a continuum between kinetic action and other, less dramatic measures with similar goals. “Hybrid containment” and kinetic military deterrence are more interlinked than ever before.

The victims of this development are likely to be those countries lacking a copper-bottomed US-backed security guarantee. This is especially true for those democracies that are European Union member states but are outside NATO and therefore vulnerable to hybrid attack.

Cyprus and Malta are known not only for their wild banking business, serving numerous dictators and rogues from Russia to China and Azerbaijan, but also for providing them physical access to the Schengen area. The murder of investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia in 2017 served as a wake-up call for the international community to seriously address the secrets hidden in Malta.

Finland is strongly dependent on Russia in terms of energy and has a significant oligarchic presence. Gennady Timchenko — one of Putin’s closest oligarchs and China envoy — has been left out from the EU sanctions list, likely because of his Finnish citizenship. Timchenko’s former business partner, MP Harry Harkimo even moved a Helsinki-based ice hockey team Jokerit from the Finnish league to the Russian KHL

Austria has experienced numerous political scandals related to Russia. According to Edward Lucas, the country was ostracized by Western intelligence services as early as 2018, likely due to suspected leaks to Russia. Given events like the so-called Ibiza affair, one can only speculate the true level of Russian penetration in Austria.

The evidence from Ukraine — and to a lesser extent, on the border between Poland and Belarus — shows the extent to which Russia is ready to act when it feels its (economic or political) assets are threatened. Sooner or later, borderland states (and other countries) without NATO membership may find themselves in a similar position. Finland shares a long (approximately 830 miles) eastern border with Russia. Both the Swedish and Finnish archipelagos would be critical for NATO defense during a military crisis in the Baltic Sea region. Malta is not far from Libya and is of high strategic importance. From the eastern coast of Cyprus, it is less than 150 miles to Russia’s Tartus military base in lawless Syria.

The Summit for Democracy can provide the spirit and will for global democratic renewal. However, countering outside influence or endemic corruption and authoritarianism within the transatlantic alliance must not forget that geopolitics and military force are the ultimate guarantor of integrity. Otherwise, kinetic deterrence or hybrid containment will fail. Likely both.

Pekka Virkki is a Helsinki-based journalist specializing in the Baltic Sea region and security. He holds an MA in Social Sciences (International Relations and Regional Studies, University of Tartu) and is finalizing an MSSc (European and Nordic Studies) at the University of Helsinki.

Europe’s Edge is an online journal covering crucial topics in the transatlantic policy debate. All opinions are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the position or views of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis.