Since the Biden administration took office in January, debates on the possibility and extent of policy coordination on China between the EU and the U.S. have been reinvigorated. The deteriorating human rights situation in China, as well as the recent imposition of asymmetric counter-sanctions by China on EU officials and members of European civil society — in response to the EU’s targeted sanctions on Chinese officials for human rights abuses in Xinjiang — may act as a catalyst for transatlantic policy coordination.

However, insights from recent public opinion polling among Europeans by the Central European Institute of Asian Studies (CEIAS) and Sinophone Borderlands project at Palacky University show that if the U.S. seeks a lasting alliance with the EU, it needs to pay closer attention to its own image in Europe, as well as the aspirations of the broader European public.

China bad, U.S. “meh”

Prospects of policy coordination are affected not only by changing perceptions of China, but also of the U.S.

According to our survey, EU nationals’ view of China has significantly deteriorated in the past three years. In nine out of 10 EU member states included in the survey, more respondents see China negatively rather than positively (Latvia being the exception). The most negative views can be found in western and northern Europe — more than 60% of German, Swedish and French respondents have either very negative or negative views of China. Even though those from southern and central European member states are slightly warmer towards China, negative opinions still prevail.

The biggest drop in favorability was recorded in Sweden, where almost 60% of respondents said their perception of China has gotten worse in the past three years. Even in Hungary, a country with a notoriously China-friendly government, 30% of respondents have had their perception become less favorable, while only 14% reported improved views.

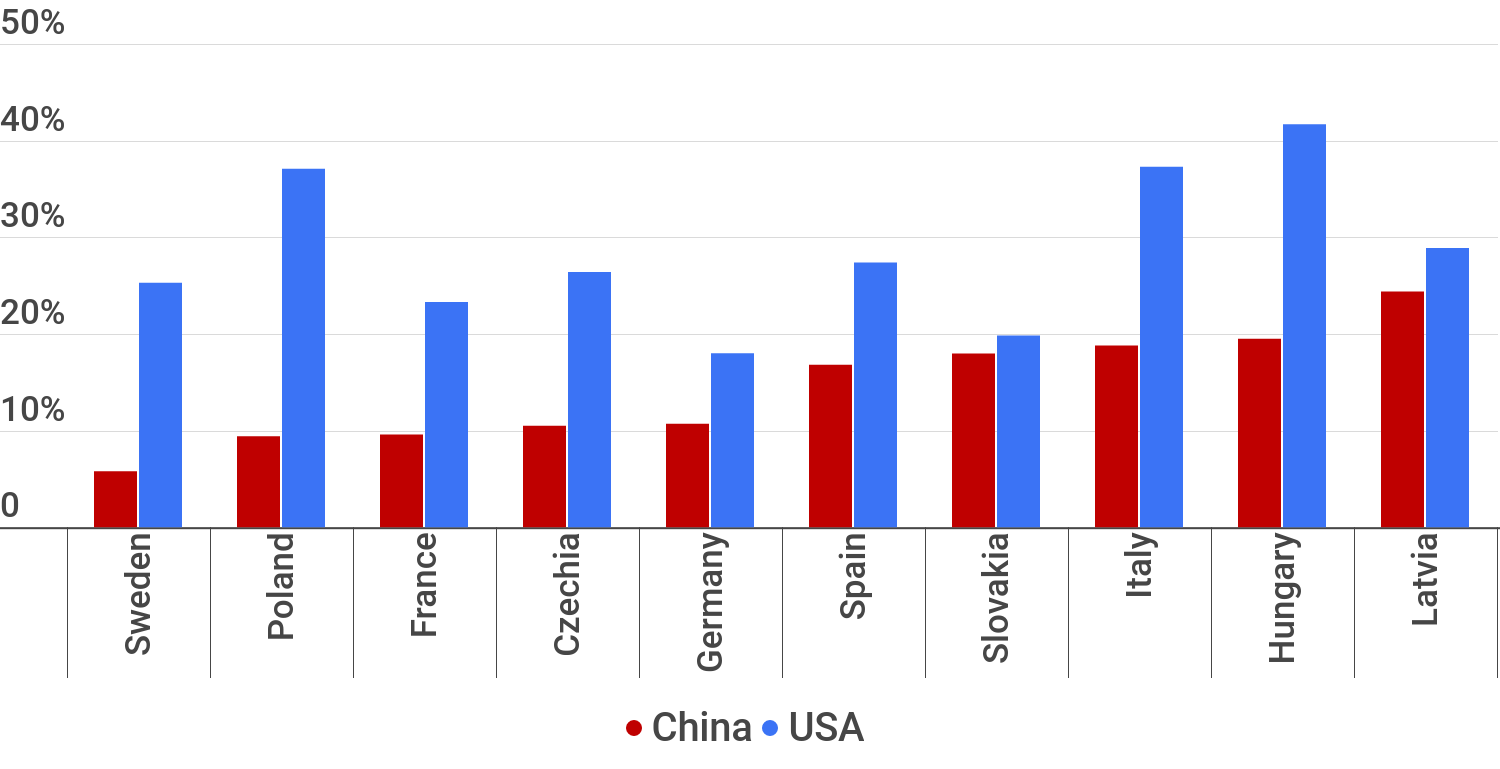

Positive feeling towards China and U.S. among Europeans (% of respondents expressing trust) Source: CEIAS & Sinophone Borderlands

Even though there is a generally negative trend for Europeans’ view of China among Europeans, the U.S. does not fare much better. Although perceptions of the U.S. are more positive, overall confidence in the U.S. is not high. In Latvia, more people see China positively than the U.S. In Slovakia, the U.S. and China record similar levels of positive views (with Russia outperforming both), while more people see the U.S. negatively than China. In Germany and France, both key EU member states, the U.S. does not fare much better — only 26% of Germans and 31% of the French people see the U.S. positively (in the case of China, it is 19% and 16% respectively). In the case of France, the U.S. is also seen more negatively than China, thus it is a more polarizing actor than China.

Despite the unfavorable views of both countries, trust in the U.S. is higher. While trust in China ranges from 5% to 25%, trust in the U.S. ranges from 18% to 42% of respondents.

Trust levels towards China and U.S. among Europeans (% of respondents expressing trust) Source: CEIAS & Sinophone Borderlands

Addressing China, but what to address?

This growing negative sentiment toward China contributes to the increasing demand for a confident European policy on China.

Foreign policy preferences of the European public echo the EU’s policy trifecta of seeing China simultaneously as a partner, a competitor, and a strategic rival.

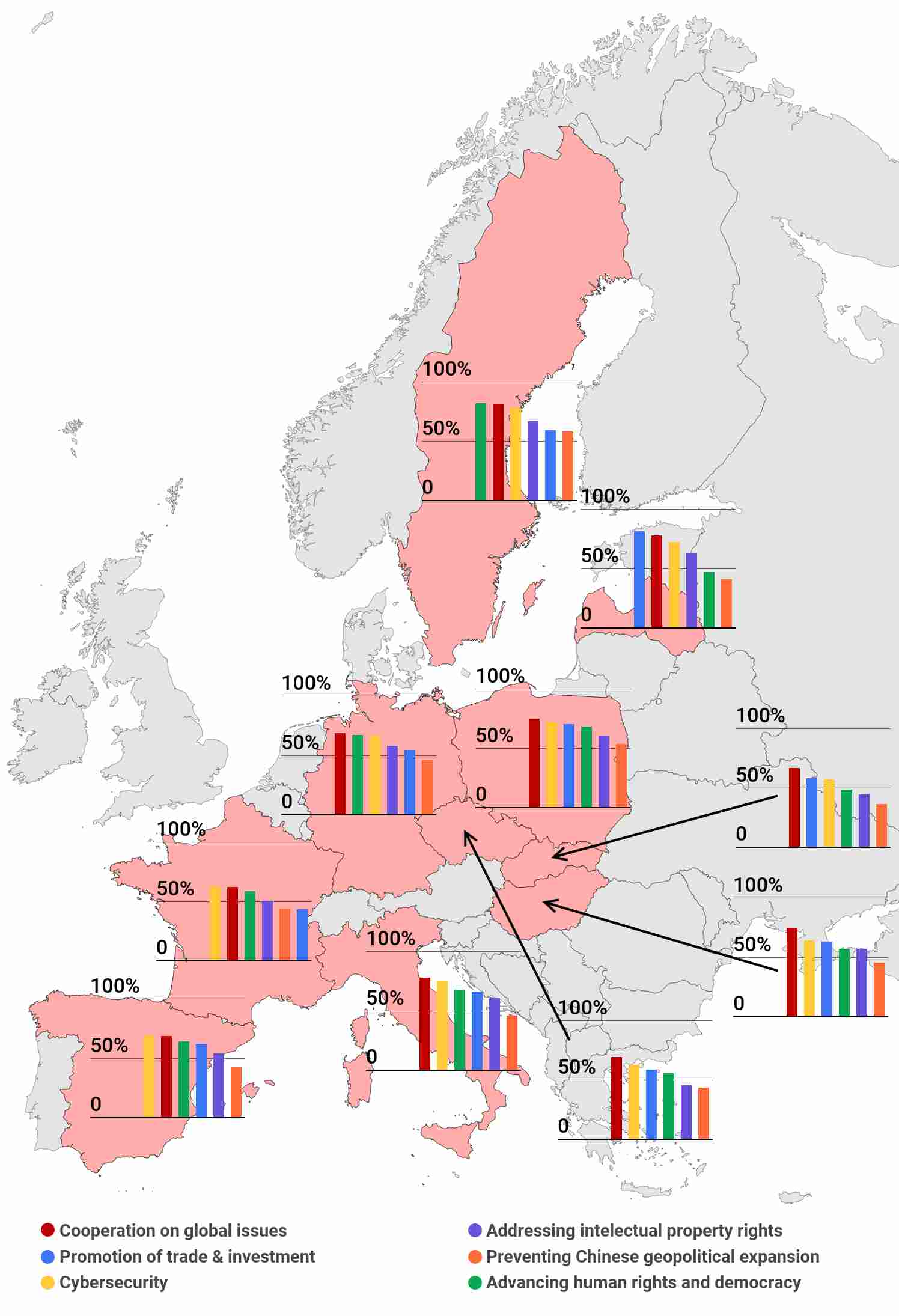

In the survey, respondents were asked to express their preferences regarding six foreign policy options: cooperation on global issues (e.g. climate change, epidemics, counter-terrorism, etc.), promotion of trade and investment, addressing cybersecurity, addressing intellectual property rights, preventing Chinese geopolitical expansion, and advancing human rights and democratic reforms.

Foreign policy priorities on China across European countries (% of respondents agreeing) Source: CEIAS & Sinophone Borderlands.

Countering China’s geopolitical expansion is the least favored policy option among respondents. This attracts majority support in just two of the 10 polled EU member states — Sweden and Poland. Even there, it is the least popular option of the six.

On the other hand, cooperation on global issues, addressing cybersecurity and human rights, and democratic reforms are quite popular options for the Europeans. Cybersecurity is the most preferred option among the French and the Spaniards (with cooperation on global issues coming a very close second). In Germany, Italy, and the Visegrad 4 countries (the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland, and Hungary), cooperation on global issues is the most favored option. Human rights are especially favored by the Swedes, where almost the same share of the population supports cooperation with China on global issues.

On human rights, Germany is a case worth examining. The promotion of human rights is the second most-favored policy option among respondents and almost half the population thinks that Germany should pursue this policy even if it causes economic damage.

Where does this leave the U.S.?

There are two implications from this survey for the U.S. and its quest for deeper coordination with the EU on China.

First, policy coordination with the U.S. on China might turn out to be a difficult sell for most Europeans. Low levels of trust levels toward the U.S. impact their enthusiasm for foreign policy alignment. While relatively high demand for this exists in Poland, other member states are much less enthusiastic. From the 10 surveyed EU members, the French have the least desire for foreign policy alignment with the U.S. In Slovakia, slightly more people would prefer to align the country’s foreign policy with China rather than with the U.S.

To improve the likelihood of the Europeans accepting a more coordinated approach with the U.S. vis-à-vis China, the Biden administration needs to invest in building goodwill among Europeans.

Second, European convictions about the appropriate approach to deal with China further constrains the U.S. in achieving broad policy coordination with the EU and its member states. Since there is very little European desire to challenge China’s geopolitical expansion, a fully-fledged alliance between the EU and U.S. is unlikely. However, a constructive relationship in some areas is possible. Agreeing to joint policies toward China on climate-related issues, joint cybersecurity (e.g. on 5G), or jointly confronting human rights abuses in China are all areas where coordination should be not only possible, but also welcomed by European public opinion.

The Biden administration can achieve success with careful and targeted policy proposals which reflect European as well as U.S. interests. Failure to do so risks further alienating European public sentiment from the U.S., putting future policy coordination on China (as well as other issues) in peril.

Matej Šimalčík is the Executive Director of the Central European Institute of Asian Studies (CEIAS), a Slovak think tank dealing with the interactions between East Asia and (Central) Europe. His research at China’s economic and political presence and influence in Central Europe, elite relations as well as the role of European legal instruments in dealing with China. He has a background in law (Masaryk University) and International Relations (University of Groningen). Currently, he is also a European China Policy Fellow at MERICS and analyst at the MapInfluenCE project.