Executive Summary

- During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has spread disinformation about the efficacy of vaccines and the virus’s origins, a shift from Beijing’s previous disinformation campaigns, which had a narrower focus on China-specific issues such as Tibet, Hong Kong, Xinjiang, and Taiwan. Most of Beijing’s COVID-19 narratives aimed at shaping perceptions of China’s response to the pandemic and only rarely targeted other countries specifically.

- Russia recycled previous narratives and exacerbated tensions in Western society while attempting some propaganda about Russian scientific prowess. Russia’s approach evolved little; it recycled previous narratives, spreading a broad range of COVID-19 disinformation.

- Evidence supports the theory that Russia seeks to strengthen itself in relative terms by weakening the West, while China seeks to strengthen itself in absolute terms.

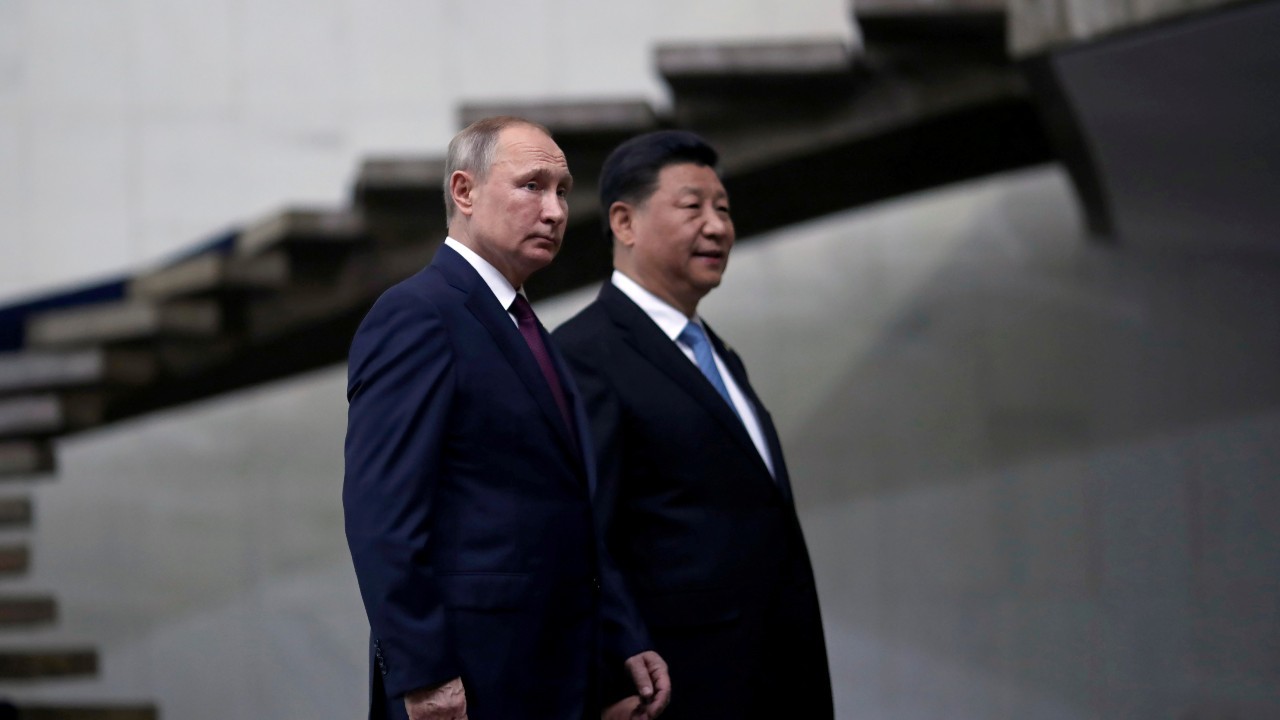

- The Kremlin and the CCP learned from each other. While limited evidence exists of explicit cooperation, instances of narrative overlap and circular amplification of disinformation show that China is following a Russian playbook with Chinese characteristics. Russia is simultaneously learning from the Chinese approach.

- The largest difference between China and Russia’s information warfare tactics remains China’s insistence on narrative consistency, compared with Russia’s “firehose of falsehoods” strategy. Even with substantially greater resources, this largely prevents Chinese narratives from swaying public opinion or polarizing societies.

- The US government, the European Union, and multinational organizations have developed a series of interventions in response. These include exposing disinformation, providing credible and authoritative public health information, imposing sanctions, investing in democratic resilience measures, setting up COVID-19 disinformation task forces, addressing disinformation through regulatory measures, countering emerging threat narratives from Russia and China, and addressing the vulnerabilities in the information and media environment.

- Digital platforms, including Twitter, Meta, YouTube, and TikTok, have increased their efforts to counter COVID-19 disinformation and misinformation via policy procedures, takedowns of inauthentic content, addition of new product features, and partnering with civil society and multinational organizations to provide credible and reliable information to global audiences. In addition, digital platforms are addressing COVID-19-related disinformation and misinformation stemming from a variety of state and non-state actors, including China and Russia.

- Several of these initiatives have proven to be effective, including cross-sectoral collaboration to facilitate identification of the threat; enforcement actions between civil society, governments, and digital platforms; and investment in resilience mechanisms, including media literacy and online games to address disinformation.

- Despite some meaningful progress, democracies need a strategic shift in the approach to information warfare. This will require gaining a deeper understanding of how adversaries think; aligning and refining transatlantic regulatory approaches; building coordination and whole-of-society information-sharing mechanisms; expanding the use of sanctions to counter disinformation; localizing and contextualizing programs and technological solutions; strengthening societal resilience through media, digital literacy, and by addressing digital authoritarianism; and building and rebuilding trust in democratic institutions.

Introduction

By Edward Lucas

Authoritarian regimes’ use of information operations (IOs) is anything but new. But the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic prompted their use on a level never before seen as Russia and China sought to exploit the crisis for geopolitical gains. The global pandemic offered a perfect opportunity for hostile state actors to launch IOs aimed at:

- weakening Western responses, processes, and institutions;

- deflecting responsibility; and

- testing new tactics for polluting the information environment and expanding their propaganda efforts.

Russia and China have been particularly active in the context of the pandemic, leveraging their significant global state-run media operations. The state-based “infodemic,” as it has come to be known, has distracted public opinion, undermined confidence in public authorities’ competence and integrity, and accumulated political and diplomatic capital. The infodemic, along with the virus itself, has become part of the global crisis.

At the beginning of the pandemic, the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA) launched a project to better understand this challenge and what lessons can be learned. Over the last 18 months, CEPA has analyzed:

- the tool kits used by Russia and China;

- the deployment and evolution of these tool kits over the course of the pandemic;

- the degree of strategic coordination between Beijing and Moscow; and

- the effectiveness of countermeasures needed to forestall Russia and China now and in the future.

In recent years, the Russian Federation has been among the most successful at spreading disinformation to sow distrust in the West. With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Kremlin’s state-backed media recycled previous disinformation campaign tactics, spreading a broad range of false information regarding the virus and the West’s incompetence in managing it. Russia’s goal focused on swaying public opinion and polarizing societies in the West while cultivating confidence in Russian scientific advancement. Prior to the pandemic, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) had primarily focused its IOs on core issues of concern, such as Tibet, Hong Kong, Xinjiang, and Taiwan. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the CCP utilized destructive and conspiratorial narratives on a new scale.

In this new environment, the Kremlin and the CCP learned from each other. The study found limited evidence of explicit cooperation. However, instances of narrative overlap and circular amplification of disinformation show that China has followed a Russian playbook with Chinese characteristics, while Russia simultaneously has learned from the Chinese approach. The largest difference in tactics remains China’s insistence on narrative consistency, compared with Russia’s “firehose of falsehoods” strategy. Even with substantially greater resources, this rigid message discipline largely prevented Chinese narratives from swaying public opinion or polarizing societies to the same degree, because, unlike Russia, China did not target content to specific audiences.

In response to this dangerous information environment, the US government, the European Union, and multilateral organizations have learned from past experiences and established a range of interventions, including:

- exposing disinformation,

- providing credible public health information,

- imposing sanctions,

- strengthening democratic institutions,

- setting up COVID-19 disinformation task forces,

- countering emerging narrative threats, and

- addressing gaps in the information space and media environment.

Digital platforms have also worked to counter disinformation and remove unverifiable content, even partnering with civil society and multinational organizations to provide credible information to users.

While this represents an improvement from previous experiences with disinformation and information warfare, the West is still playing catch-up. What the West needs is a strategic shift in its approach to information warfare. This should consist of seven pillars:

- Understand how the adversary thinks

- Develop, refine, and align on transatlantic regulatory approaches

- Stand up a coordination and information-sharing whole-of-society mechanism for information integrity and resilience

- Develop a comprehensive deterrence strategy and leverage traditional tools of statecraft

- Localize and contextualize interventions

- Build and rebuild trust in democratic institutions

- Strengthen societal resilience by advancing media and digital literacy, countering digital authoritarianism, and measuring the impact of policy interventions

The pandemic has revealed that the West can still be caught flatfooted in the information space. But that does not mean the West cannot turn that around. The war in Ukraine has had many lessons for the world, one of which is that Russia, which had the world’s most formidable information warfare apparatus, is losing the information war. The malign IOs of the Kremlin melted when confronted with the positive, offensive message and the power of the free press. This is a fight that can be won: the West just needs a new approach.

Note on Terminology

China’s COVID-19 information operations (IOs) are a significant threat, but research and policy responses should be prioritized efficiently, and researchers should be clear about their definition of disinformation as opposed to broader IOs. For the purposes of this paper, CEPA defines disinformation as narratives purposefully meant to mislead and only partially based on the truth. While propaganda and other IO tools are polarizing, disruptive, and spread to support state interests, they require a different response than messages more akin to conspiracy theories or biased versions of the truth. This paper examines both disinformation and propaganda as important tools of IOs spread to support Chinese and Russian interests during the pandemic.

REPORTS

Acknowledgments

This report is the result of research contributed over the course of 18 months by a team of researchers including Ben Dubow, James Lamond, Jake Morris, Corina Rebegea, and Vera Zakem. All opinions are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the position or views of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA).

Post-Mortem is part of CEPA’s broader work aimed at tracking and evaluating Russian and Chinese information operations around COVID-19. This report is a compendium of Information Bedlam, a report published in March 2021 examining the preexisting literature on Russian and Chinese COVID-19 information operations; Jabbed in the Back, a report published in December 2021 assessing Russian and Chinese disinformation narratives; and Owning the Conversation, a report published in March 2022 analyzing public and private sector responses to COVID-19 information operations. All three reports were updated in April 2022. The updates are reflected in this report. This work benefited from feedback from a working group of experts and practitioners, convened by CEPA, working on Russian and Chinese information operations. A special thanks to Bret Shafer and Olga Lautman for their thoughtful feedback. This work was made possible with the generous support of the Smith Richardson Foundation.

This report is the result of research contributed over the course of 18 months by a team of researchers including Ben Dubow, James Lamond, Jake Morris, Corina Rebegea, and Vera Zakem. All opinions are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the position or views of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA).