When Russia’s President Vladimir Putin openly menaces NATO, it is time to take note. Having issued unrealistic demands designed to ensure the impotence of the alliance, we can no longer deny that war is more than possible.

If deterrence fails — and that’s far from inevitable — and Russian Federation forces do take the next step in kinetic operations, what will it look like? And, just as important, what should we be doing?

If Russian forces begin new kinetic operations beyond their seven-year campaign in Eastern Ukraine, it will follow on the heels of some Kremlin pretext to justify deployment of “humanitarian forces” to fix a fictitious problem.

The idea of “little green men”, the unbadged Russians used to take Crimea, now seems almost cartoonish; what comes next will be much more sophisticated. Russian special forces, or Spetznaz, will hit key targets across Ukraine, to confuse and deceive as much as to neutralize decision-making. Cyber strikes and sea-launched cruise missile strikes, accompanied by Russian Air Force fixed wing aircraft, will initiate this next phase, aimed at paralyzing Ukrainian command and control, communications, and transportation. Airborne and helicopter-borne forces will be inserted to seize key infrastructure; and while these can obviously move fast, they cannot hold out for too long without reinforcement or sustainment.

The operational objective in the first days will be the isolation of Ukraine from the Azov Sea and the Black Sea, with main operations focused along both coastlines; these are easier to sustain, probably involve fewer casualties, and are more likely to encounter those few Ukrainians who might be less interested in strong resistance.

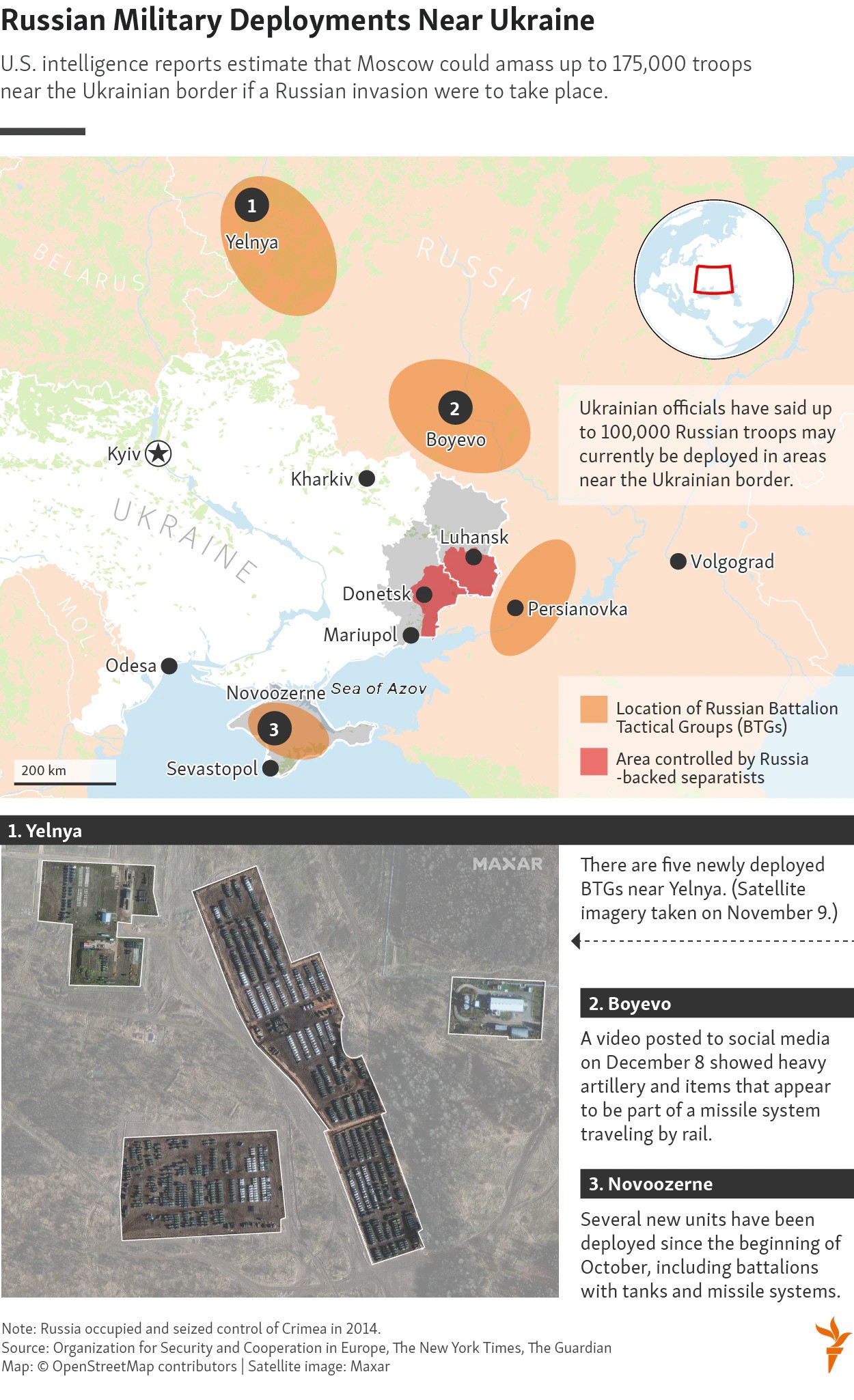

Russia has deployed forces on several fronts and not just on land. Its Caspian Flotilla never returned to the Caspian Sea after the “exercises” in April; it remains in the Azov Sea and has been rehearsing amphibious operations. Russia’s generals will nonetheless have to consider time-space factors, especially when both sides have drones and the ability to see deep and to strike deep, so long convoys and large assemblies of vehicles/equipment become very vulnerable as they move toward the front. Therefore, forces will move on multiple parallel routes to disperse their forces, perhaps even from the north and via Belarus.

The most likely course of action for major ground formations will be for Russian forces in Donbas to “fix” the Ukrainian forces to their front, pinning them down so that they cannot move, while more mobile forces will emerge from Crimea and as part of amphibious operations to seize the remaining coastline of the Azov Sea between Mariupol and Crimea.

Russian military use of railroads has always impressed me. They’ll move as much as possible using this form of transportation to get as close as possible to attack positions. They know the US and NATO will be watching of course (using a wide variety of methods, including satellites, sensor-fitted reconnaissance aircraft, electronic eavesdropping, and whatever human intelligence might be available) so there will be a lot of deception involved, much as the Egyptians were able to mask their force concentrations from Israeli intelligence in the lead up to the Yom Kippur war in 1973.

So what can we do to strengthen our deterrence efforts and effect? Clearly, the US Government is looking at increasing aid to Ukraine, and has reportedly sent cyberwarfare teams to the country for the expected Russian digital offensive. But its message is far from consistent, with a critical shipment of Q36 counter-fire radar held up. The White House needs to agree on its message and stick to it.

There are many reasonable steps that can be taken in coordination with our allies to assist the defense of a friendly country and I would recommend the following steps that would make a difference:

- resume delivery immediately of all equipment already promised and deliver capabilities that could have an immediate effect, without long training or extensive overheads;

- support training/preparations for Integrated air/missile defense, even if it’s conducted back at Ramstein Air Force Base in Germany;

- support mobility exercises in Ukraine; an expanded conflict will be much more mobile than the fighting of the last six years;

- support additional deliveries of drones, either from Turkey or the US

- enhance Ukrainian shore-based anti-ship missile capabilities; and

- support the training of Ukrainian territorial forces and militia — a classic mission for US Army Special Forces “Green Berets.”

Finally, we must seize the Initiative. The Kremlin should be worrying about what we are doing whereas we have hitherto always responded to whatever they are saying or doing. With the combined economic, diplomatic and military power of the members of NATO and the EU, there is no reason that we should not be calling the shots, and from a favorable diplomatic position.

For starters, here are four ideas I think we should consider:

- Announce the development of a NATO Black Sea strategy that will encompass diplomacy and economic development, backed up by increased security cooperation with all of our partners and allies in the region, including a renewed effort to repair our relationship with our Turkish allies. Most of the discussions and statements from the White House over the last few weeks concern policy decisions (like whether to give Ukraine more Javelin anti-tank missiles.) That’s an issue for my tactical recommendations, above. It’s not a strategy.

- Signal to Moscow that frequent violations of Article XII of the Montreux Convention by Russian submarines have gained attention and could result in restrictions on further movement by the Russian Navy through the Turkish straits. Turkey has several levers by which it could enforce Montreux. This would obviously require extensive diplomatic liaison between the US and Turkey.

- Let it be known that we are considering a blockade of Russia’s naval base in Tartus, Syria.

- Take steps to make the Commander of the Black Sea Fleet feel uncomfortable in his illegal base in Sevastopol and likewise the Commander of the Caspian Flotilla which is still sitting in the Azov Sea. For example, announce delivery to Ukraine of anti-ship capabilities, maritime unmanned systems, and increased deployments of NATO naval capabilities, all within the constraints of the Montreux Convention. We are nowhere near that level now.

I am more concerned today than I was even a week ago that the Kremlin will take the next kinetic steps forward. Our lack of unified effort in all domains and mixed messages from the White House add to my concerns. Strong, clear signals from the White House and a strong, unified front with our European allies and partners are what is required. The alternative is a slide into large-scale conflict in Europe.

Lieut. General (Ret.) Ben Hodges is Pershing Chair in Strategic Studies at the Center for European Policy Analysis in Washington, DC. He was Commanding General, United States Army Europe from 2014 to 2017.

Europe’s Edge is an online journal covering crucial topics in the transatlantic policy debate. All opinions are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the position or views of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis.