#CEEDisinfoWeek is series of articles highlighting the current disinformation landscape in Central and Eastern Europe, and how external and home-grown disinformation has adapted to take advantage of the coronavirus pandemic.

January 6th, 2021 will likely remain in the minds of Europeans as the day that a crowd of Americans turned against everything that America historically represented to the world. Fewer will see in it the underlying malign foreign influence operation unfolding for years against the background of (at best) a complacent administration in Washington. The operation was aimed at influencing elections, but also helping radicalize the local population online in ways that end up undermining democracy, stability, and social cohesion.

Across the Atlantic, Brexit was exposed sooner as a similar – and successful – endeavor. In both cases, the public image will still remain that of a part of ‘we, the people’ upending the status quo, whether at the polls or in the streets. Behind it lies a much more intricate web of domestic and foreign collusion.

In Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), the same kind of mechanism has so far resulted in the democratic backsliding of Poland and Hungary: the former under the leadership of a government hostile to Russia, but fully playing into the hands of Russian interests; the latter in full-fledged, brazen cooperation with both Moscow and Beijing. A bit more to the south, overlapping Russian and Chinese interests have turned the largest and most influential country in the Western Balkans, Serbia, from the poster child of the region’s EU accession, into a puppet of foreign powers and corrupt domestic interests. A staunch US ally and the most consistently pro-European country in the region, Romania came close to succumbing to a government of little ideological conviction but committed to roll back anti-corruption reforms to preserve power and impunity at all costs. It was ousted by the voters in 2019, but one year later, the socially conservative electorate it left floating propelled a brand-new far-right party straight into parliament, the first time in over 10 years.

Going forward, Russian and Chinese malign foreign influence (MFI) in CEE should be analyzed and faced on all three dimensions along which it deploys: the influencers, the influencing, and the influenced.

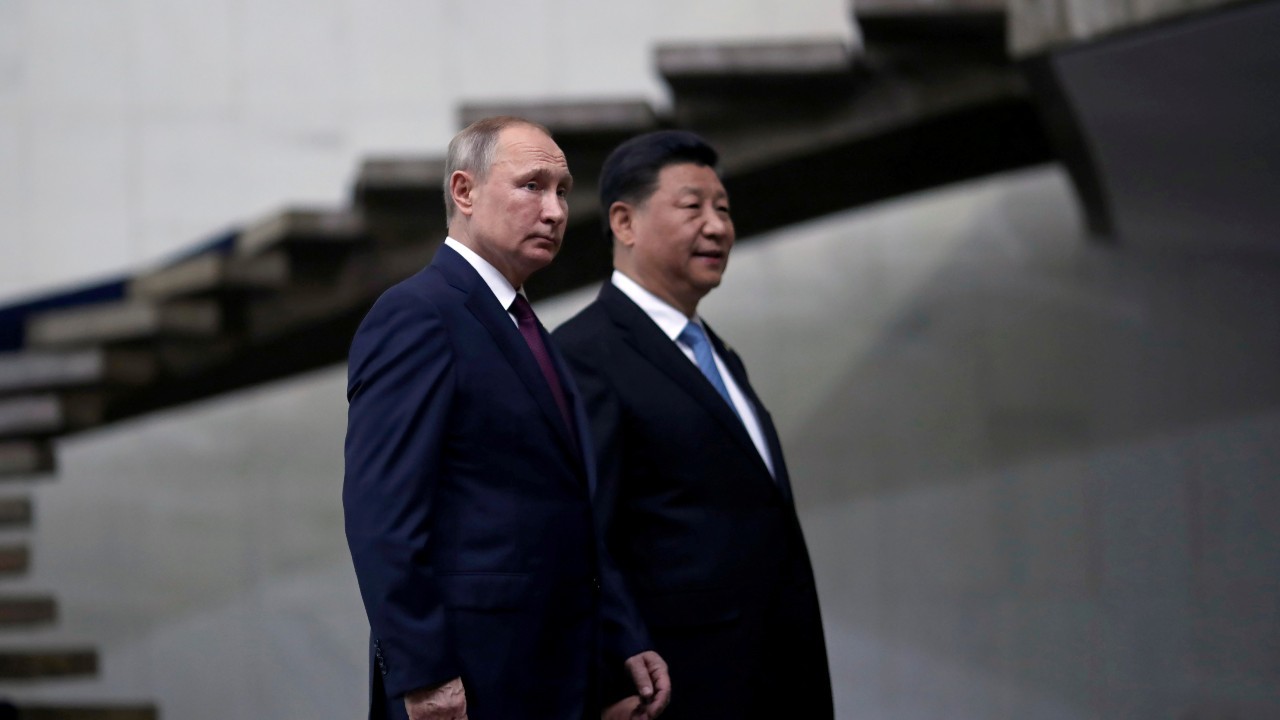

The influencers have partly overlapping objectives, strategies, and tactics. Russia’s is to preserve Putin’s power structure domestically and – to this end – create a “near abroad” space of influence insulated from Western and democratic competition (which could give ideas to its own citizens). Its methods combine military dominance with a set of values opposed to Western liberal democracy (Slavic brotherhood, traditional values, Orthodoxy). The Kremlin uses cultural ties, historical narratives, or psychological levers to foster socio-political fragmentation and polarization, leading to weak, dysfunctional states that either reject Western institutions and values altogether, or exhaust the capacity and/or willingness of the West to support democracy. Once that is accomplished, Russia has a free hand to use its other arsenal of influence and manipulation: organized crime, business-political nexus of corrupt interests, funding political parties, or civic movements/civil society organizations, etc.

China’s agenda is apparently more benign because it often uses legitimate means, but it is essentially like being strangled by the anaconda that wraps around you till you can’t breathe. Beijing has so far sought to secure for itself a favorable investment and trade environment and has focused more on directly influencing decision-makers than the masses. To advance its global political and economic agenda, however, it has a direct interest in diminishing Western power and challenging the Western-dominated rules-based order and rule of law set. Until recently, it has done so less actively than it has engaged in promoting its own economic interests (resulting in a degree of dependence on Beijing of both CEE and Europe as a whole that is very hard to walk back within any optimistic timeframe!). The onset of COVID-19 though has left an embattled China scrambling for options to quickly repair its international reputation damaged by “the Wuhan virus.” However, Beijing has been able to do so at spectacular speed, thanks to its opportunistic synergies with Russia, which have put China in the enviable position of simply having to reach out with an offer to those domestic agents which Moscow had already identified and prepped, incentivizing them to step up their game.

Raising the costs (both material and reputational) for hostile actors conducting such influence operations is paramount, and it requires early detection, exposure, and response.

In the information space, however, the influencing is done by constructing fundamental narratives that create in the minds of a vulnerable audience binary oppositions: “democracy and Western capitalism do not really serve the interests of the citizens,” “liberal values are morally bankrupt and threaten traditional identities and ways of life,” “the U.S./ EU/ NATO are imperialist powers,” “the West is the aggressor who seeks to box Russia and China into a corner to eliminate opposition,” “national governments are vassals of great powers/supranational bodies,” etc. Neither Russia nor China insists that the “manipulated” need to turn into their admirers. In countries like Romania or Poland, both Atlanticists with vivid memories of communism and Russian dominance, that would be an unlikely outcome. Yet enough people in both countries, while still proclaiming loyalty to a pro-Western strategic orientation, have proved to be rather easily swayed away from Western values to support anti-democratic forces.

In CEE, as everywhere else, the battleground, therefore, turns domestic, with the tremendous ethical and practical challenge of identifying a state’s own citizens as “the enemy within.” The influenced are (quite massive) vulnerable groups, who experience polarization and inequality, caused by uneven economic development and modernization, and disillusionment with political representation; or who are frustrated with the mixed results of integration into the West. In these permeable populations, malign foreign influence heightens a sense of threat around societal values and amplifies grievances with respect to state, society, or the West. Eventually, it perverts the argument of self-expression and exercise of democratic freedoms to incite insurrection against the very fundamentals of democratic order. At the decision-making level, hostile states corrupt influential voices and discredit institutions to further aggravate the low confidence in government.

Given the region’s history of communist oppression, accelerated and uneven transition, and lingering differences from the West (both cultural and developmental), driving a wedge between society and its leaders is a relatively easy and inexpensive game, with a high and quick return on investment.

The pandemic has recently shown how lack of trust in elected authorities can immediately (not in an abstract future) translate into active resistance to life-saving measures and an economic and humanitarian crisis of proportions. Investment in societal resilience is, therefore, the only effective answer, coupled with the relentless investment in building up democratic culture and independent institutions. In CEE, fortunately, the experience of pre-NATO/EU accession cooperation with the West is still fresh, the actors themselves still active, an invaluable resource to tap into and reactivate.