When Italy became the biggest European Union (EU) member state to join the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2019, its decision was met with concern and shock on both sides of the Atlantic. Yet almost three years later, Italy has distanced itself from China and recommitted to its Western partners, while Europe, as a whole, has become more concerned with Chinese inroads on the continent, and Chinese investment in Europe has dramatically declined. The issue is far from resolved — for Europe and for Italy, the coming years will be full of critical decisions about managing relations with China alongside existing economic and security partners.

Now that 2022 is firmly in view, more changes are coming to Europe. Next month, Italy will elect a new president. Though the office is largely ceremonial, the incumbent Sergio Mattarella helped bring Mario Draghi in to serve as prime minister following the resignation of Giuseppe Conte. Draghi is one potential successor to Mattarella. Another candidate is former prime minister, Silvio Berlusconi. Whoever takes up residence in the Palazzo del Quirinale will oversee a fractious Chamber of Deputies, one that will face an election of its own before June 2023. This general election will be marked by a steep reduction in the number of politicians elected; the lower house in the Palazzo Montecitorio will have only 400 members instead of 630, and the Senate will be reduced to 200 from 315. This trimmer parliament will face the fallout of the Covid economic crisis and questions about Italy’s role within European and global politics.

At the heart of these issues is how Italy will navigate its relationship with China. Italy, notoriously, and perhaps without fully realizing the geopolitical impact of its actions, became the first G-7 country to join China’s BRI in 2019. Strong allied criticism followed the signing of “29 deals worth €2.5 billion.” European political leaders, Emmanuel Macron foremost among them, lamented a lack of coordination among European nations in relations with China. The US too voiced its concerns.

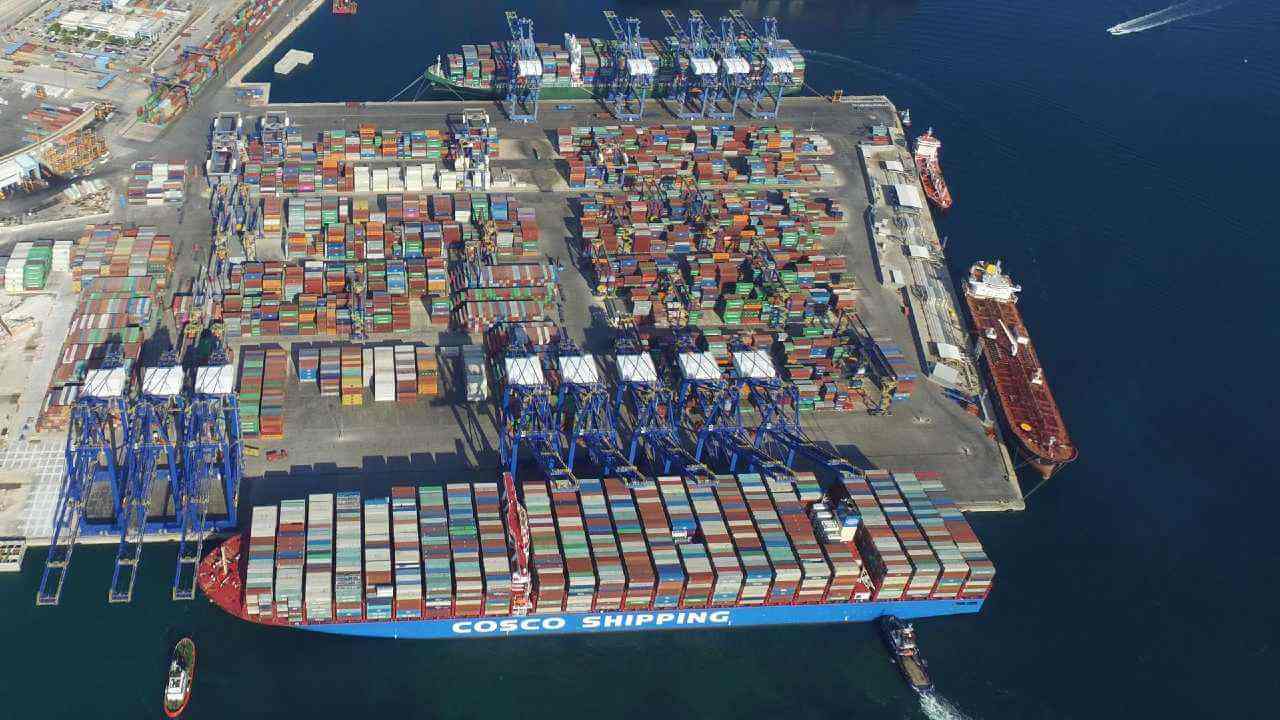

Though signed with much fanfare in March 2019, the agreement had pre-existing roots. Some active collaborations were simply formalized. In other cases, promises were made, but have not materialized. Prime Minister Paolo Gentiloni visited China in 2017 for the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation. Economy and Finance minister Giovanni Tria visited in 2018, openly seeking to “strengthen economic cooperation.” Italy witnessed the increasing importance of the Mediterranean to Chinese trade, embodied by Cosco’s purchase of a controlling share in the Greek port of Piraeus outside of Athens in 2016, and worried that new trading routes through the Balkans might eclipse its ports. In the runup to this period, Chinese investment in Europe was practically doubling on an annual basis: €6.5bn in 2013, €14.6bn in 2014, €20.7bn in 2015, and €44.2bn in 2016.

In the meantime, Italy’s economy slipped into recession in 2018. A general election in March of that year brought a populist coalition of the Lega and the Movimento 5 Stelle (The 5-Star Movement) to power. This alliance of political newcomers hoped that a partnership with China would increase trade, help to pull the economy out of recession, and allow it to chart a bold new partnership, capitalizing on China’s growing stature in the world. This ideal reached back to the years of the original Silk Road and the role of Italian merchants like Marco Polo in bringing Chinese products to Europe, and enriching powerful states like Venice, in the process.

Italy’s economic troubles compounded problems with its European partners. Many Italians already harbored resentment against Europe for failing to provide it with sufficient support at the peak of the migration crisis of 2015. And during 2018, the EU and Italy engaged in a prolonged confrontation over Italy’s budget proposals and debt levels.

Nearly three years later, China’s image has been battered by blowback from the crackdown on pro-democracy protestors in Hong Kong, the effects of the coronavirus pandemic, and scathing reports from the United Nations detailing “serious human rights violations” in Xinjiang against China’s Uyghur minority, while one legal commission even made a “very credible case” that China is committing genocide. Less than nine months after signing the Belt and Road memorandum, the Italian Parliament passed a resolution supporting the protestors in Hong Kong. More recently, it joined other European nations in calling Chinese officials to account for atrocities in Xinjiang.

Sharp rhetoric from the Trump administration, the US-China trade war, and rising European concerns about Chinese inroads on the continent have exacerbated China’s problems. Confronting these headwinds, Chinese investment in Europe has declined precipitously from a peak of €44.2bn in 2016 to €6.5bn in 2020. With the coronavirus still a major factor and European countries increasingly wary of Chinese investment, this situation is unlikely to change.

In economic terms, the agreements have also been disappointing for Italy. As argued in a comprehensive report by the Torino World Affairs Institute (T.wai), Italy’s calculations of increased commercial and economic relations with China “turned out to be optimistic, at the very least, if not completely fallacious.” Bilateral trade has not produced massive dividends. Investment has also become more problematic due to European hesitancy about exposing critical industries and sharing technologies with China.

Even when it pursued the Belt and Road agreement, Italy’s government remained cautious about granting too much access to Chinese companies. Three days before the BRI agreements were signed, the Italian parliament passed a law extending the government’s “golden power” to veto corporate acquisitions to 5G companies, and the following year, the Conte government blocked a Chinese acquisition using this legislation. Prime Minister Draghi has since used this line of defense three times: blocking the sale of a semi-conductor company, a seed producer, and, most recently, stopping a Chinese company from setting up a joint venture with Applied Material Italy’s screen printing operations, which are used in the fabrication of silicon solar cells.

Diplomatically, Draghi has also reasserted Italy’s commitment to the Western alliance, ending what has been characterized as “his predecessors’ ambiguous position toward Russia and China.” The Biden administration continues to emphasize “great power competition” — meaning competition with China and Russia. To that end, US policymakers are hard at work deepening traditional alliances and building new ties. In that context, American-Italian relations have a newfound sense of significance. Fresh opportunities exist for both countries to recommit themselves to transatlantic cooperation in the economic, political, and security spheres.

China tried to build a new highway to Europe through Italy, but it may be that Italy and its traditional companions continue to travel that route together, more closely linked than any time since the end of the Cold War.

Andrew R. Novo is a nonresident fellow with CEPA’s Transatlantic Defense and Security program and is a Professor of Strategic Studies at the National Defense University, Washington, DC.

The views expressed do not reflect the views of the US Government, the Department of Defense, or the National Defense University.

Europe’s Edge is an online journal covering crucial topics in the transatlantic policy debate. All opinions are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the position or views of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis.