A new form of Orientalism makes the West susceptible to propaganda narratives from China that ultimately aren’t even primarily intended for them.

That Western societies are under pressure from Chinese propaganda is no news at all. What is less frequently appreciated is that our susceptibility to it stems from a long tradition of exoticizing the Chinese themselves—out of a tradition of Orientalism that, paradoxically, has today melded with homegrown authoritarian tendencies among Western populists, to create a fertile ground for Beijing’s efforts at influence games.

Orientalism 2.0 is characterized by a barely-concealed, fearful admiration of the recent achievements of the East. Indeed, China today has replaced Japan of the 1970s as the country which “does things differently” and is about to overcome the old democracies.

When China’s Premier Zhou Enlai was asked by Henry Kissinger in 1971 what he thought the impact of the French Revolution had been, he replied cryptically, “Too early to say.” This hoary story encapsulates the whole dynamic: the father of Western Realpolitik meets the enigmatic Eastern sage; Western quarrelsome short-termism is contrasted with Chinese strategic patience; “our” superficiality clashes with “their” sense of history.

Except it was revealed later by Chas Freeman, Kissinger’s interpreter at that meeting, that Zhou Enlai simply misunderstood the question. He thought it was about student revolts in Paris in May 1968, not the actual French Revolution of 1789. “Too early to say” was the politically correct answer of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 1971, which had been disappointed by yet another failed attempt to crush capitalism in the streets of France three years earlier. In other words, Zhou was not speaking the timeless language of Confucius and Sun Tzu, but only repeating slogans from The People’s Daily, the newspaper of the Chinese Communist Party—propaganda designed to manipulate the hearts and minds of the Chinese people, who at that time knew almost nothing of the West. And why was this glaringly obvious — and to some extent funny — mistake not exposed right away? Chas Freedman writes, “I distinctly remember the exchange. There was a misunderstanding that was too delicious to invite correction.” Delicious indeed—a story too good to be debunked because it played on the cultural biases of the international chattering classes. In a certain sense, it was propaganda-by-invitation.

We have made a habit of this. We repeat pompous nonsense coming from Chinese leaders and seek deeper meanings where there are none. We are tempted to believe, and often unwittingly circulate stories about the triumphs of the regime, and ignore grim realities, which are all too visible. The Little Red Book—a collection of 267 aphorisms by Mao —was mentioned during British parliamentary debates in 2015 as a reliable guide to Chinese long-term strategy. Of course, it is nothing of the sort. The regime is opaque and non-democratic, and its internal fractures and brutal power games remain hidden. Few people from the inner circle manage to bypass the censorship and speak about the uncertainty, opportunistic behavior, and haphazard decision-making that guides Beijing’s policy.

A recent book explains how, during the murderous Cultural Revolution unleashed by Mao, one faction of the Red Guards emerged triumphant, and became the “generation of Deng Xiaoping”—the same so-called pragmatists who, ten years later, opened fire on the people in Tiananmen Square. The current president, Xi Jinping, is the son of an important leader who was abused by the radicals during the waning turbulent years of Mao’s rule but got the upper hand and settled scores with them later. Family history and clan networks matter in Chinese politics at least as much as ideology and strategies. The supposed anti-corruption campaign lauched by Xi after taking office needs to be seen for what it is—clannish score-settling, not an attempt at “reform,” as the CCP organs described it. Many in the West take these explanations seriously, however, because these narratives are the only things that are available.

Supporters of China’s authoritarian development ignore the degree to which Chinese policy is the result not so much of long-term planning, but opportunistic decisions and score-settling among groups within the party, the army, and the business sector. Plus ça change. They should read the classic book by Kornai Janos about how the socialist system worked in reality, beyond the party documents. Five-year plans did exist, but mostly to be honored ritually, while in reality, it was all a matter of improvisation across the board, in an attempt to reconcile conflicting pressures emerging from the nature of the regime. Fake news and disinformation have always been natural emanations from this kind of system.

Yes, the turbo-capitalism governed with Leninist methods in modern China is not the same thing as Mao’s communism. The country’s progress in GDP per capita, creating a modern infrastructure and pulling hundreds of millions out of extreme poverty, cannot be denied. But nor is it unique, save for its scale. It is what one expects when a modicum of normality is allowed back into a long-suffering economy, and as a society makes the gradual transition from rural self-sufficiency to urbanization and industrialization. It is a huge historical one-off, inflated after the thoroughgoing disasters of the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution. Indeed, there are already signs that the effect is leveling off.

Similarly, while it cannot be denied that China managed the COVID crisis with ruthless efficiency, is it really surprising that a totalitarian regime is the best in the world at imposing lockdowns, controlling the movement of people—and silencing them?

Or consider the much-discussed Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the subject of endless books in the West marveling at Chinese strategic daring and boldness. In reality, it is nothing more than a vast propaganda platform with ever-shifting dimensions (no clear list of projects, no precise budget) used by well-connected economic groups inside China to carve business niches abroad at the expense of their domestic rivals. It is an endogenous byproduct of merciless struggles inside an opaque regime that is treated as fearsome wisdom abroad.

Under President Xi, domestic indoctrination has become a more explicit goal. The United Front, an organization with a broad mandate to supervise and integrate citizens who are not Communist Party members, is increasingly assertive. It infiltrates and controls the private sector, making sure its priorities align with the official ones. The COVID crisis was seen by the Party as a perfect opportunity to demonstrate to its citizens the advantages of military-style mobilization and the suppression of dissent.

We outside China are just collateral damage of this gigantic effort at propaganda and manipulation targeting the Chinese people themselves. In the spring of 2020, during the first wave of the pandemic, planes with medical supplies were landing in Belgrade or Rome, and thank you speeches were being delivered by Western leaders, with Chinese ambassador standing nearby. The primary audience for this show was back home in China, not Western voters. The “Health Silk Road”, a COVID-era extension of the nebulous BRI concept, is meant to be, above all, a testimony to the Chinese people of how indispensable their leaders have become globally.

When that narrative is punctured by news about the substandard quality of Chinese medical supplies, or, more recently, of the low efficiency of its vaccine, Beijing gets aggressive, spreading disinformation left and right. Pfizer’s vaccine is badmouthed. Top officials and anchors on Chinese state media circulated stories about unexplained deaths in Norway as a result of vaccination. Again, however, it is not the rest of the world, but their own citizens who are being indoctrinated. If in the pursuit of this goal, confusion and distrust in vaccination spreads globally, so be it. Stability at home is what matters most, and what preoccupies authorities in Beijing above all.

Russian strategic disinformation has always been more subtle and adaptable to context, which in turn makes it far more effective. The Kremlin is more familiar with the cultural habits of the target countries, especially those in Eastern Europe, as a result of a long-shared history. By contrast, Chinese propaganda abroad comes in the form of robotic recitation of bullet points prepared at home, largely a summary of what state media tells the Chinese people. When challenged, Chinese diplomats shift to “wolf warrior” aggression.

But most of the time they don’t need to. We have enough mavericks in Europe—politicians who admire authoritarianism or influencers with anti-Western inclinations—who are ready to collect internet memes about the superiority of the Chinese model and build their own narratives. Comparative ignorance among Europeans about Chinese realities makes their task all the easier. This is especially true in the newer member states in Central and Eastern Europe, and in the Western Balkans. China only has to be present in the region with investments (some commercially sound, some less so) and a small version of BRI called “the 17+1 initiative”, framed in equally ambiguous, lofty party-speak, for the local propaganda-by-invitation to grow organically. The Chinese can count on Orientalism 2.0 to serve them well—and paper over the glaring cracks in their shoddy plans and projects.

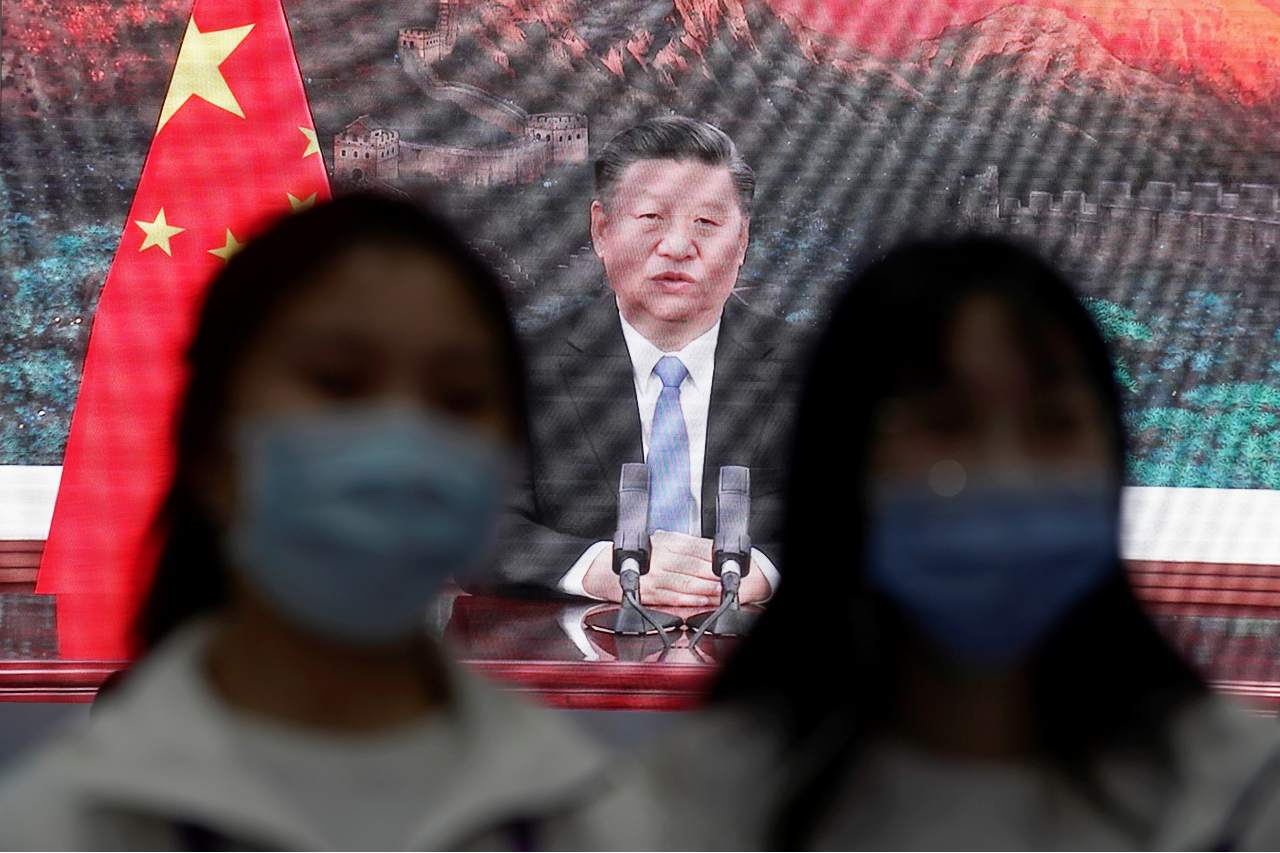

Photo: China’s President Xi Jinping is seen on a screen in the media center as he speaks at the opening ceremony of the third China International Import Expo (CIIE) in Shanghai, China November 4, 2020. Credit: REUTERS/Aly Song

WP Post Author

Sorin Ioniță

January 30, 2021

Common Crisis is a CEPA analytical series on the implications of COVID-19 for the transatlantic relationship. All opinions are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the position or views of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis.