Note: Dr. Benjamin L. Schmitt testified before Senate and House members of the U.S. Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe on European energy security post-Russia on 07 June 2022, in Washington, D.C.

More details on the hearing can be found on the Commission website here. The full written testimony of Dr. Schmitt that was provided for the Congressional record can be downloaded in PDF form here, and is provided in full, below.

Overview

Chairman Cardin, Co-Chairman Cohen, Distinguished Senate and House Members of the United States Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe, and distinguished fellow witnesses. Thank you for holding a hearing today on an issue as vital to Transatlantic national security and US foreign policy interests as supporting Europe’s energy security.

My name is Dr. Benjamin L. Schmitt, and I am a research associate at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics at Harvard University, serving as project development scientist. At Harvard, my work focuses on supporting the technical design, project management, and deployment of novel instrumentation and infrastructure that will comprise next-generation experimental cosmology telescopes aimed at imaging the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) radiation from the US National Science Foundation-administered Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station in Antarctica. I am also an associate of the Harvard-Ukrainian Research Institute, a senior fellow of the Democratic Resilience Program at the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA) in Washington, and co-founder of the Duke University Space Diplomacy Lab as a Fellow of the Duke University Center for International and Global Studies “Rethinking Diplomacy” Program. From 2008 to 2009, I also had the honor of representing the United States in Germany as a US Fulbright Research Fellow at the Max-Planck-Institut für Kernphysik, in Heidelberg.

A proud native of Rochester, New York, I now reside in Boston, Massachusetts. I have previously served as European Energy Security Advisor at the US Department of State, initially entering the US government as the 2015 IEEE Department of State Science and Technology Policy fellow. During my tenure at State, I focused on advancing evidence-based diplomatic engagement vital to supporting the energy and national security interests of the Transatlantic community, with a particular focus on supporting the resilience of NATO’s Eastern Flank as it faced Russian malign energy activities. While at State, I had the privilege of traveling to work with energy, diplomatic, and national security officials from nearly every EU member state, as well as the European institutions in Brussels.

I also frequently visited Ukraine in my duties, including a temporary duty rotation covering the energy security portfolio at US Embassy Kyiv during late-Summer 2018. During that rotation, I was dispatched by then Ambassador Marie “Masha” Yovanovitch and Deputy Chief of Mission George Kent on a trip to Strilkove in Eastern Ukraine, just kilometers from the administrative boundary line with Russian-occupied Crimea on the Azov Sea coastline. There I visited a major Ukrainian offshore natural gas facility and met with regional energy, education, and military officials to underscore the United States’ strong support for Ukraine’s energy security and territorial integrity.

Now, 104 days since Russia began its criminal assault against Ukrainian sovereignty – that facility and the entire Ukrainian Azov Sea coastline is now illegally occupied by forces of the Putin regime.

This outcome wasn’t inevitable.

Scholars will debate for years what specifically prompted Russian President Vladimir Putin to launch his large-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 – chilling historical revanchism and neo-colonial impulses seem to be among the leading candidates. At the same time, we must begin to identify the policy frameworks that have been taken by the Transatlantic community since Putin came to power, which likely emboldened the Russian leader to engage in his brutal adventurism against Ukrainian freedom.

With heavy fighting ongoing in Ukraine – and the wounds of Bucha and Mariupol still open and bleeding – the Transatlantic community doesn’t have the luxury of time to search for an effective path forward in countering this new phase of Russian aggression. Urgent anticipatory diplomacy is needed.

This is especially true concerning Europe’s dependence on Russian energy resources because Putin’s Kremlin has weaponized energy against Europe for years and because hydrocarbon revenues play an outsized role in funding Moscow’s war-making capability. Given this reality, we need to take a lessons-learned approach to identify energy policies that have been successful to curb the Kremlin’s energy influence in the lead up to the war, as well as being clear-eyed about mistakes that were made so that they are not repeated.

Three key lessons that should guide future European energy security policymaking include:

- First, energy and critical infrastructure proposals advanced by authoritarian nations like Russia are “not just commercial deals.”

- Second, energy diversification infrastructure has been effective at countering Russian energy weaponization.

- Third, sanctions have been an effective tool to slow and stop Kremlin malign energy influence.

On the first lesson, given total state control in authoritarian nations like Russia, nearly every sector of society can be weaponized to advance geopolitical aims, including areas like cyberspace, supply chains, and space assets. This reality means that foreign policy responses must now be deliberately multidisciplinary and include basic science and technology analysis in the traditional national security process given the underlying technical nature of the threats. Russia’s long and sordid history of weaponizing energy against Europe is a key example of such authoritarian activity, including numerous gas cutoffs of Ukraine for political blackmail, including in 2009, 2014, 2015, and 2018.

In 2021, the Kremlin intentionally limited natural gas volumes exported to European storages, many of which were owned by Kremlin-controlled Gazprom. This created EU-wide gas scarcity that limited the latitude of foreign policy responses to Putin’s invasion of Ukraine as hostilities began during the height of the European heating season in February 2022.

Russia also uses energy proposals – like the Nord Stream 1 and 2 pipelines – to advance strategic corruption and elite capture in Europe. This includes former senior officials leaving office only to end up working for Russian state-owned energy firms like Gazprom and Rosneft and their subsidiaries. You have likely heard of the case of former German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder infamously taking multiple such roles – including at Rosneft and majority-Gazprom-controlled Nord Stream AG – after leaving office.

But over the last decade a growing list of officials have followed in his footsteps, including from France, Austria, and beyond. Just a few such examples include former French Prime Minister François Fillon joining the board of Russian state-owned oil group Zaroubejneft, and former Austrian Foreign Minister Karin Kneissl joining the board of Kremlin-controlled Rosneft in 2021. The trend became so notorious it got a name – Schröderization – and the practice dangerously undermines confidence in democratic norms in the face of authoritarian influence.

On the second lesson, in recent weeks, Moscow has increased its energy pressure to deter a united European response to its invasion of Ukraine, cutting off gas exports to Poland, Bulgaria, Finland, Denmark, and the Netherlands. However, effective energy infrastructure policies driven under the European Energy Union framework and supported by US energy diplomacy, have made these countries resilient to Russia’s cutoffs. In fact, Poland and Bulgaria were able to neutralize pressure from the cutoffs by developing many such projects, such as Poland’s Świnoujście LNG terminal and BalticPipe natural gas pipeline, as well as Bulgaria’s long-awaited Interconnector Greece-Bulgaria set to come online this year.

And finally, the third lesson. Let’s be clear: Congress has been consistently right with its sanctions policies to limit Russian malign energy influence over the years. This is particularly true when it comes to measures to stop the Kremlin-backed Nord Stream 2 pipeline, including discretionary sanctions against the project under the 2017 Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA), as well as the mandatory, technology-calibrated sanctions measures that were included in the 2020 and 2021 National Defense Authorization Acts.

Nord Stream 2 was a long-running geostrategic anchor that Germany clung to even as Russia openly created a gas crisis last year, and likely emboldened Putin’s confidence that energy pressure could limit Western pushback on his looming invasion. Nevertheless, despite long-running narratives that sanctions could not stop Nord Stream 2, Congressional sanctions worked: the Biden Administration finally sanctioned Nord Stream 2 AG and its corporate officers in the hours before Russia’s invasion, leading to reports of its insolvency, and hopefully ending the project for good.

Nevertheless, energy sanctions measures can always be made tighter to ensure that the Kremlin can’t exploit perceived loopholes. For example, the avoidance of sanctions in 2021 against a vessel whose registered ownership was by a so-called “Climate Foundation” which was set up in northeastern Germany had raised concerns at the time. This is because the entity was fact nearly fully funded by the Gazprom-backed Nord Stream 2 consortium, though set up as a government-related entity at the German state level, reportedly in an effort to avoid sanctions. The implications of not learning from this lesson in the future are clear. If left uncorrected, the move could provide a framework for other authoritarian nations to create similar shell “foundations” within countries allied with the United States to evade sanctions designations and thereby undermine the efficacy of broader US counter threat financing programs globally.

With these lessons in mind, the United States and Europe need to take urgent action to increase energy sanctions on the Kremlin to pressure it to relent in its ongoing aggression against Ukraine. The Biden Administration’s embargo on Russian hydrocarbon imports was a vital first step, and last week’s partial oil embargo of Russia by the EU was another step in the right direction.

But as the Guardian reported last week, during the first two months of Putin’s assault on Ukraine, “EU countries are estimated to have paid a total of 39 billion Euros for Russian energy, more than double the sum they have given to help Ukraine defend itself.” This is unacceptable if global democracies are going to be successful in helping Ukraine defend its sovereignty and territorial integrity.

Therefore, to pressure the Kremlin to relent in its aggression against Ukraine, increase Europe’s energy resiliency, and counter longstanding strategic corruption and elite capture concerns associated with Russian state-owned-enterprises, I offer three recommendations:

- We must dramatically increase Transatlantic energy sanctions on the Putin regime.

Our collective goal must be a total oil and gas embargo of exports from the Russian Federation. Until we get to zero, we must:

- Increase tariffs on Russian energy to deter purchases by energy traders, and – particularly for oil – to continue to depress the Russian Urals crude oil price with respect to the global Brent oil benchmark.

- Implement controlled sales regimes such as escrow accounts so that Russia can’t immediately cash in from interim energy sales en route to zero.

- The US and EU should issue joint sanctions to permanently stop Russian energy export pipelines like Nord Stream 1 and TurkStream 2. Measures should also be included to expand export controls restrictions on technologies supporting Russia’s energy sector, on insurers and maritime certification providers, as well as on technical service providers for Russian energy ventures, especially those that can help aid sanctions evasion, like firms providing ship-to-ship transfer services.

- We need to keep leading global energy diplomacy to help the EU secure alternatives to Russian energy resources, while supporting a wartime level of effort to deploy energy diversification infrastructure to make Europe independent of Russian energy.

The Biden Administration’s global energy diplomacy – led by Senior Energy Advisor Amos Hochstein – has been doing an excellent job advancing efforts to help the EU identify and secure alternative oil and gas volumes to replace Russian resources; this needs to continue. Further infrastructure measures should include the deployment of floating LNG terminals to increase natural gas import capacity at strategic locations around Europe’s periphery. Special interest should be given to locations where appropriate onshore infrastructure already exists to speed project development, such as repurposing the gas hub built for Nord Stream 1 and 2 at Lubmin, Germany to instead allow for LNG imports from non-Russian sources. Urgent legal and regulatory steps must also be taken to end ownership of critical oil and gas facilities by Kremlin-controlled entities across the EU.

- We must curb Kremlin Strategic Corruption in Western Democracies.

Although several senior European officials have begun to leave their post-government positions working for Kremlin state-owned-enterprises in recent weeks, the trend has not reached a definitive end. To ensure that this practice does not re-emerge to undermine confidence in democratic norms once more, Congress should first work with European parliaments to issue a joint-statement defining a Transatlantic norm stating that nations on both sides of the Atlantic will pass legislation to bar post-government employment at Russian state-owned-enterprises. This shouldn’t be controversial and can be done today. Then this legislation should be passed, for the United States in the form of the Stop Helping America’s Malign Enemies, or SHAME Act, to set a Transatlantic example to help end the trend of Schröderization for good.

In this written testimony, I draw on years of front-line energy diplomacy experience and analysis conducted inside and outside of government. I will draw upon analysis that I have published on the European energy security issue set, including in articles authored and co-authored with Foreign Policy magazine, CEPA, the Atlantic Council, the Harvard International Review, and the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute, among others.

Additionally, for the sanctions discussion, I will draw upon analysis that I have coauthored on Russia energy sanctions as a member of the International Working Group on Russia Sanctions, organized this year under the leadership of Ambassador Michael McFaul at Stanford University.

The testimony is structured to highlight:

- The path of European energy infrastructure, regulatory, and sanctions policy before the onset of Russia’s renewed aggression against Ukraine in February 2022.

- How Russia has weaponized its energy exports to the European continent since Putin assumed power, including via energy resource cutoffs, abnormal market actions, as well as trends of disinformation, strategic corruption, and elite capture (e.g. former European officials taking positions at Russian state-owned-enterprises – the so-called “Schröderization” of Europe).

- The significant role that energy security has had in the Transatlantic response to Putin’s invasion of Ukraine thus far.

- Further energy sanctions actions that global democracies can take to help increase pressure on the Putin regime to help Ukraine in its current struggle to restore its sovereignty and territorial integrity.

- The steps that the Transatlantic community must urgently take to ensure that, henceforth, Europe can become independent from Russian energy, and undo the structural dependence on Russian energy that resulted in decades of strategic vulnerability to Kremlin-initiated energy coercion.

European Energy Security Policy Before Russia’s 2022 Invasion of Ukraine

Europe’s acute energy dependence on Russian energy resources isn’t a recent phenomenon. In fact, the origins of European dependence on Russian oil and gas can be traced back to the Soviet Era. In that period, nations on the Eastern side of the Iron Curtain were largely dependent on Soviet-deployed oil and gas pipeline infrastructure emanating from the territory of Russia, which in general could be manipulated by Moscow to place pressure on wayward members of the USSR. Furthermore, beginning in the late 1960’s, German Chancellor Willy Brandt’s policy of rapprochement with the Soviet bloc – referred to as Ostpolitik – initiated a series of oil and gas pipeline projects that long worried Western leaders – most notably Congressional leaders and successive-Presidential Administrations in Washington – that these projects would increase the strategic vulnerability of Western Europe to the Soviet Union.

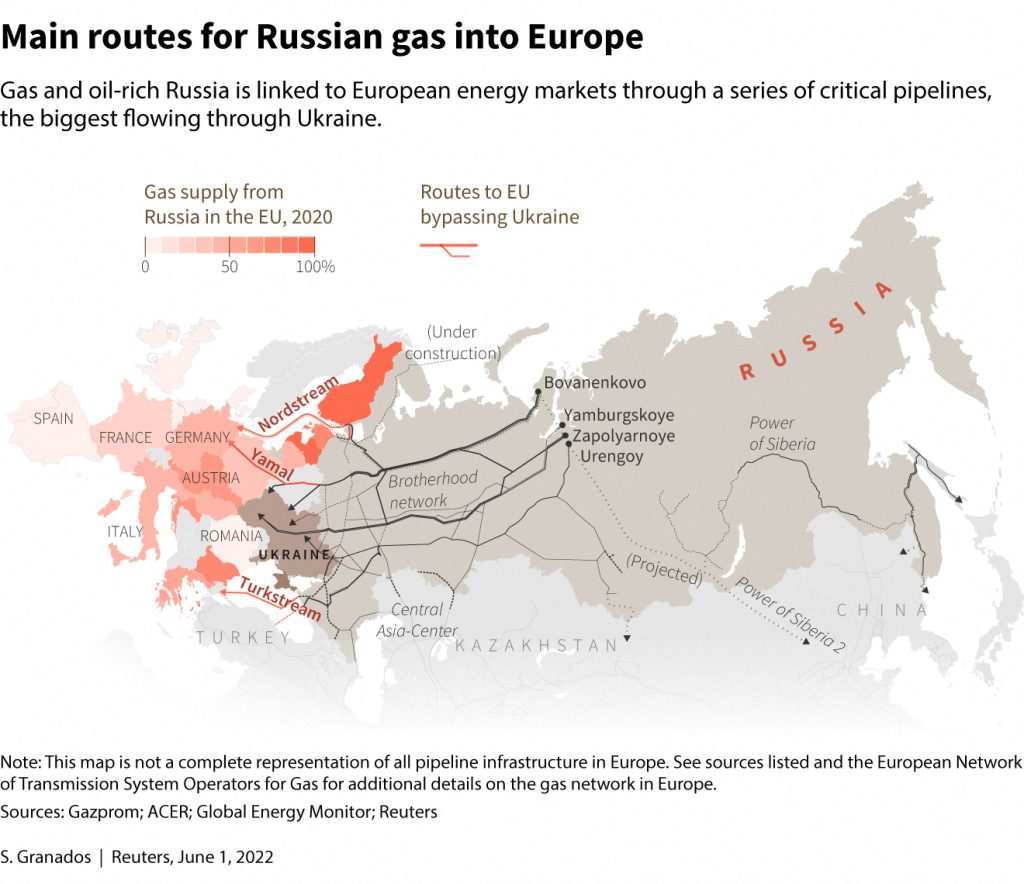

These concerns would persist long after the fall of the Soviet Union. Over the past two decades, the Russian Federation under President Vladimir Putin has demonstrated a long and sordid history of using energy as a political weapon against the Transatlantic community, particularly Ukraine. For example, the Kremlin under Vladimir Putin’s leadership has carried out a myriad of high-profile cutoffs of the Ukrainian gas transmission system, including notable restrictions in 2009, 2014, 2015, and 2018. Despite these clear examples of Kremlin energy manipulation, politicians and business leaders across Western Europe continued to pursue a policy of deep energy cooperation with Putin’s Russia, including the development of the Kremlin’s marquee malign influence project of the past decade – the Nord Stream 2 natural gas pipeline across the Baltic Sea.

Despite project defenders in countries like Germany and Austria long claiming Nord Stream 2 was just a commercial project, the pipeline was in fact advanced by Moscow to allow the Kremlin to significantly reduce or end Russian natural gas shipments to European markets via Ukraine. Despite claims by Gazprom that the pipeline was aimed at bringing significant new gas volumes to Western Europe, the design of Nord Stream 2 and its planned onshore extension in Germany, EUGAL, betrayed this narrative. EUGAL was principally directed Eastward toward the Czech Republic, en route to OMV’s gas distribution hub at Baumgarten, Austria, the de facto end of the current Ukrainian gas transit route from Russia to Europe. Under 20 percent of the project’s capacity was actually allocated for direct delivery westward, while the remaining majority was aimed at replacing volumes currently transiting Ukraine.

For years, policy leaders on both sides of the Atlantic worried that a loss of gas shipments via the Ukrainian gas transmission system would hurt Kyiv’s economic and national security interests. Ukraine would lose both transit revenues and some of its already undermined security. Without Russia’s dependence on the Ukrainian gas transit system for delivery of its gas to Europe—some of which is in close physical proximity to the then post-2014 line of contact in Eastern Ukraine—there would be one less check on Moscow’s aggressive behavior in the Donbas or elsewhere in Ukraine. This prediction has become all the more prescient given the Kremlin’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 as Nord Stream 2 was in its final phases of preparation to begin operation.

It is important to note how the Nord Stream 2 project was not just a commercial deal, and never just a business proposition. At the time of Nord Stream 2’s announcement in 2015, several of the European then-shareholders—notably, OMV and BASF/Wintershall—signed lucrative agreements with Gazprom for gas production rights in the Russian Federation, which had been briefly put on hold following Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea and aggression in Eastern Ukraine. For Moscow, a hard-hitting 2018 Sberbank analysis revealed that Gazprom’s investment in projects like Nord Stream 2 are in fact significantly “value destructive” for its shareholders. Instead of normal commerciality, the projects are used as a means of enriching contractors with close ties to Russian president Vladimir Putin, including companies controlled by Russian oligarchs already targeted under the US sanctions program, such as Gennady Timchenko and Arkady Rotenberg.

Moscow’s use of geopolitical projects like Nord Stream 2 as a means of channeling benefits to favored Russian oligarchs is not limited to domestic allies of Mr. Putin. Notoriously, former German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder advocated for the first Nord Stream pipeline while in office and was appointed Chairman of Nord Stream AG shortly after leaving. Since then, he has become one of Putin’s most effective Trojan horses in Europe. In the following years, the list of “Schröderized” officials (e.g. former senior European officials that have left government service and then received posts at Kremlin-controlled state-owned-enterprises or their subsidiaries) has grown.

Former Austrian Chancellor Christian Kern, who penned a strong letter coauthored by then-German Foreign Minister Sigmar Gabriel decrying the 2017 US Countering America’s Adversaries through Sanctions Act (CAATSA), was appointed to the board of Kremlin-controlled Russian Railways. Additionally, former Austrian finance minister Hans Jörg Schelling left his post, only to be appointed as a senior advisor to Nord Stream 2 AG just three months after leaving office. Furthermore, Austrian Foreign Minister Karin Kneissl accepted an appointment to the board of Kremlin-controlled oil enterprise Rosneft in 2021. This came following her post-government activity providing written commentary for Russian propaganda network RT, and after she infamously invited Putin to her wedding. And finally, in mid-2021, former French Prime Minister François Fillon, long known for espousing pro-Putin views and calls to end EU sanctions on the Kremlin, was nominated by Russian authorities to be the “representative of the Russian Federation” on the board of directors of Russian state-owned oil group Zaroubejneft. The announcement sparked fresh outrage on both sides of the Atlantic over Fillon, who in 2020 was sentenced to prison time for embezzling French public funds.

With this trend – often referred to as strategic corruption or elite capture – in mind, imagine if George W. Bush or Barack Obama were currently working on behalf of China’s Huawei. This wouldn’t just be a major political story in Washington, it would be the only story. Sadly, the electorate in some Western European nations for years accepted the Schröderized status quo, and therefore there appeared to be little political motivation for former senior officials to resist becoming well-compensated conduits of Russian malign influence, especially in the absence of legislation, regulations, or norms barring such conduct. Not to mention the lack of concern that the CEO of Nord Stream 2 was none other than Putin-confidant and ex-Stasi officer, Matthias Warnig.

In spite of the risks of Nord Stream 2 being highlighted by successive US Congresses and Administrations since the announcement of the project – Obama, Trump, and Biden all raised their concerns with Berlin – German leaders, in particular, clung to the development of the project even as the Kremlin continued to engage in egregious behavior in the international community, from extrajudicial assassinations, to cyberattacks against democratic institutions (including Germany’s own Bundestag), to the brazen poisoning of Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny by a variant of the weapons-grade nerve agent Novichok in 2020.

Instead, some Berlin-based Nord Stream 2 proponents claimed that the project was an important way to continue cooperation with Russia, in what was then an already low point in the modern relationship. They invoked the Ostpolitik of the late Cold War, which involved West German cooperation with Moscow on Russian energy exports to Western Europe. One problem with this analogy was that Western Europe arguably needed the additional Russian gas volumes in the 1970s, but wasn’t the case driving Nord Stream 2, given that it was merely a diversionary pipeline for volumes that were already reaching Western Europe via the Ukrainian gas transmission system.

The more significant problem was that former chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany Willy Brandt’s Ostpolitik was not just about taking favorable policy actions for Moscow in the hope of improved relations. It was also about shoring up relations with Eastern bloc states, including Poland and East Germany.

Thus, in the Nord Stream 2 context, Berlin’s willingness to cooperate with Moscow on the project clashed with Ostpolitik in that it was in opposition to the views of most of its Eastern European Union neighbors, as well as Ukraine, Moldova, and others, including the United Kingdom, Sweden, and Canada. Even Germany, which has not suffered multiple direct gas cutoffs like its European neighbors to the East, has also faced Kremlin-sourced energy injury, such as the 2017 Siemens-gas-turbines-to-Crimea scandal, for which the German company initiated criminal proceedings. From this perspective, Nord Stream 2 was deeply flawed Ostpolitik.

Additionally, as I argued in an analysis coauthored with Anders Aslund for the Atlantic Council in March 2021 (references to which are included throughout this written testimony related to the trend of Schröderization), a corollary to the so-called “Neue Ostpolitik” approach to Putin’s Kremlin that was represented by the pursuit of Nord Stream 2 after its announcement in mid-2015, was the political concept advocated by some German politicians called “Wandel durch Handel,” or in English, “Change Through Trade.”

The “Wandel durch Handel” foreign policy concept was reinvigorated in the early 2000s by former Chancellor Schröder, based on the idea that increasing trade relations with authoritarian regimes like Putin’s Russia would allow Western regulatory norms and rule of law to flow naturally upstream, slowly transforming kleptocracies into liberal democratic states. Ultimately, from that time until the onset of Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, there was arguably a lot of “Handel” (trade) without much Kremlin “Wandel” (change) toward liberal democratic norms to show for it.

Indeed, the yearslong list of Russian malign activities toward the Transatlantic community capped off by Russia’s February 2022 large-scale invasion of Ukraine, offers strong repudiation of the political concepts of “Neue Ostpolitik,” “Wandel durch Handel,” to say nothing of wider constructs of “realist” foreign policy.

These trends all set the stage for the roughly 9-month period immediately preceding the Russian military invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. In spite of US sanctions effectively stopping the physical construction of Nord Stream 2 in December 2019 with the passage of sanctions against pipelaying vessels included in the 2020 National Defense Authorization Act, failure to fully implement further congressionally-mandated, technology-calibrated sanctions aimed at impeding the completion of Nord Stream 2 throughout the first half of 2021 led to the physical completion of Nord Stream 2 by mid-2021.

Meanwhile, during Autumn 2021, the Kremlin proceeded to explicitly link an increase in gas supply deliveries to EU storages in exchange for a rapid certification of the Moscow-backed Nord Stream 2 pipeline, contributing to a gas crisis across the EU in the months ahead of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. To be clear, that gas crisis across the EU was not solely initiated by Kremlin energy market actions. Key crisis contributors included a colder-than-normal spring, calmer-than-normal summer (leading to a drop in electricity production from EU wind turbines), and an unanticipated jump in global demand (especially from Chinese energy consumers) driven by a faster-than-expected market recovery post-COVID-19.

However, during the period of 2021 during which gas storages are generally filled, Kremlin-controlled Gazprom took steps that actively tightened the market further, declining to follow its expected annual practice of sending additional gas flows along existing routes (including the Belarus-Poland-Germany Yamal-Europe pipeline, or the Ukrainian gas transmission system where spare capacity existed) beyond contracted volumes to the gas storage facilities in Europe that it had ownership stakes in ahead of the onset of Winter 2021-2022.

As far as motive, Kremlin and parliamentary officials in Moscow left European energy security analysts with hardly any mystery to solve. Konstantin Kosachyov, a Representative of Russia’s Federation Council expressed a not-even-remotely-veiled disdain for EU energy diversification policies when he chortled that “we cannot ride to the rescue just to compensate for mistakes that we didn’t commit,” while seemingly linking further Russian gas exports to alleviate the crisis with undefined “mutually beneficial agreements.”

Meanwhile, the Kremlin’s envoy to the EU, Vladimir Chizhov, linked an increase in Russian gas exports to Europe with a change in Brussels’ policy approach to Moscow, warning EU officials to “change adversary to partner and things get resolved easier…when the EU finds enough political will to do this, they will know where to find us.”

And most directly, on October 21st, Russian President Vladimir Putin linked Gazprom’s future decisions to a rapid German certification of Nord Stream 2, declaring that “if the German regulator hands its clearance for supplies tomorrow, supplies of 17.5 billion cubic meters will start the day after tomorrow.” Add to this headlines in October 2021 from the Financial Times documenting how “Gazprom offered Moldova new gas deal in exchange for weaker EU ties” – underscoring Moscow’s continued ire aimed at the pro-EU policies pursued by Moldovan President Maia Sandu and her government.

In all these instances, linking the delivery of gas supplies with various geopolitical and regulatory demands appeared to cross any reasonable threshold of a state using energy as a political weapon. Which leads to the inevitable question: where was the resulting Transatlantic response? After all, as a part of a July 2021 joint statement between the United States and Germany, both governments agreed that “should Russia attempt to use energy as a weapon or commit further aggressive acts against Ukraine, Germany will take action at the national level and press for effective measures at the European level, including sanctions, to limit Russian export capabilities to Europe in the Energy sector, including gas, and/or in other economically relevant sectors.”

The response from German government officials at the time still in Chancellor Angela Merkel’s caretaker government fell far short of fulfilling Berlin’s commitment under this joint statement. There was little from German officials to define Moscow’s actions and statements as the very epitome of energy weaponization. More concerning, amidst Europe’s gravest gas crisis in recent memory, the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi) released an assessment on October 26 2022 issued to the German Federal Energy Regulatory Authority (Bundesnetzagentur) declaring that the Ministry had “come to the conclusion that the issuing of [Nord Stream 2] certification does not endanger the security of the gas supply to the Federal Republic of Germany and the European Union.”

The BMWi announcement came just three business days after Polish gas firm PGNiG had submitted the latest of several international comments to the BMWi assessment process. In the press release of its comment, PGNiG “underlined the risks for security of gas supplies to the European Union resulting from launching of this pipeline.” Furthermore, the announcement came just two business days after Putin’s linkage of quick Russian gas increases should Nord Stream 2 be quickly certified. Moreover, on October 27 2022, just one business day after the BMWi announcement, Putin announced he had ordered Gazprom to finally increase gas transfers to EU-based storage facilities (though Gazprom’s market actions didn’t fully follow through with this announcement in the weeks and months that followed).

With such a timeline, and in the absence of forceful repudiation by German officials of malign Kremlin energy declarations, it was difficult to avoid at least the public perception that Moscow’s energy pressure may have been working. This potential should have given officials in Berlin pause, since such a perception could undermine confidence in independent Western regulatory institutions and liberalized market policies that Kremlin officials so publicly have disdained through their statements and actions.

In the weeks that followed, on November 16 news emerged that Germany’s national energy regulatory authority, the Bundesnetzagentur (BNetzA), had suspended the certification process needed for Nord Stream 2 to come into operation. With headlines like “Germany Blocks Nord Stream 2 Pipeline Approval,” and “Germany Suspends Approval of Nord Stream 2 Gas Pipeline,” policy observers could be forgiven for believing Germany had decided on a major policy shift to (finally) acknowledge and respond to the project’s threat to European energy and national security interests.

Except, it hadn’t. According to the Financial Times, the temporary suspension was purely procedural, rather than a policy decision to reject the Kremlin’s overt weaponization of energy, thus still leaving Berlin’s vow to the Biden Administration unfulfilled. The “Nord Stream 2 project is creating a German subsidiary to own and operate the German section of the pipeline in response to EU ‘unbundling regulations,’ which require that companies producing, transporting, and distributing gas within the bloc are separate entities,” the paper reported. Furthermore, the article cited Pawel Majewski, CEO of Poland’s PGNiG, as stating at the time that not only “is [it] not possible to certify a subsidiary of Nord Stream 2 AG as an independent operator of the gas pipeline,” but also that it is “not possible to establish an operator applying EU law only in the territorial waters of Germany.”

In other words, it appeared that the German regulator would simply allow Gazprom to refile paperwork to advance one of the several legal arguments floated by the Kremlin-controlled enterprise during the development phases of Nord Stream 2. The aim? Creating a structure that would have allowed Nord Stream 2 to circumvent the full force of EU market liberalization policies, which would otherwise undermine Russia’s monopolistic business model.

The FT report suggests that Gazprom was working to attempt to advance a scheme that I described in December 2019 analysis for the Atlantic Council. This proposal would “involve creating a shell company under which Gazprom could sell the last 12 nautical miles of the pipeline as it enters the German territorial sea to avoid having to comply with ownership unbundling requirements” of the 2019 Gas Directive update of the EU Third Energy Package.

Of course, understanding project ownership was key in this scenario. Although physically located in Zug, Switzerland, Nord Stream 2 AG was 100% owned and operated by Kremlin-controlled Gazprom, and thus should have been considered de facto a Russian state-owned-enterprise in legal and policy terms. If Kremlin-controlled Nord Stream 2 AG simply were to create a German shell company to operate the last few nautical miles of the pipeline, as it would ultimately do in early 2022 with the announcement of the (short-lived) German subsidiary Gas for Europe GmbH, it would have been hard to think of this arrangement as having been meaningful ownership unbundling.

That understanding of ownership should have extended to sanctions policy as well. In December 2020, the German tabloid, Bild, reported on a plan “to trick the US government.” The alleged scheme would allow “the eastern German state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern [to] set up a foundation with the stated purpose of combating climate change, but whose real objective would be to provide support solely to Nord Stream 2-related firms, somehow avoiding a sanctions designation in the process.”

Making matters worse, the so-called public sector foundation was reportedly set up with over 99% of its funding from the Gazprom-backed Nord Stream 2 consortium — to the tune of €20m ($22.5m) from the Nord Stream 2 consortium and just €200,000 in funding from Mecklenburg-Vorpommern.

This local German local government proposal appeared to have been a response to a concept that arose earlier in 2020 that the inclusion of certification language in the 2020 NDAA would inadvertently lead to sanctions on EU government entities. Since then, it was (rightly) clarified in the 2021 NDAA that US sanctions policy intent was not aimed at allied government entities themselves, by including an “exception for certain governments and government entities” in Europe that are “not operating as a business enterprise.”

That last clause was highly relevant since it appeared to address the establishment of any quasi-government entity within US, allied, and partner nations aimed at advancing the commercial interests of the Russian pipeline itself. Furthermore, the existing 2020 NDAA law, took into account ideas such as transfers to a Gazprom-backed “climate foundation,” stating that sanctions designations would include “foreign persons that have knowingly sold, leased, or provided the vessels for the construction of [the] project or facilitated deceptive or structured transactions to provide such vessels.”

Despite Congress closing these sanctions loopholes, it appears that Nord Stream 2 sanctions issued by the Biden Administration on November 22, 2021 did not properly taken this language into account. That announcement “list[ed] two vessels and one Russia-linked entity, Transadria Ltd., involved in the Nord Stream 2 pipeline. Transadria Ltd. [would] be sanctioned under PEESA [Protecting Europe’s Energy Security Act], and its vessel, the Marlin, [would] be identified as blocked property.”

While these sanctions were not designed to stop Nord Stream 2, the story of the other listed vessel is the bigger concern here. According to a Bloomberg report, “another vessel, the Blue Ship, was cited for its work on the pipeline, but not sanctioned because it belong[ed] to an entity affiliated with the German government.” Per German media reports, on July 1, 2021 Blue Ship — which earlier this year engaged in sanctionable stone-laying work along the Nord Stream 2 route — had its registered ownership transferred to the aforementioned entity set up with primarily Gazprom funding: Klima und Umweltschutz MV.

The Biden Administration’s elective act of specifying that Blue Ship was engaging in sanctionable activities but justifying not sanctioning the vessel by claiming the ship’s affiliation with the German government was more concerning than its mere impact on the future of Nord Stream 2. If left uncorrected, the move would provide a clear framework for other authoritarian nations currently targeted under the US sanctions program to create similar cynical shell “foundations” to evade designation and undermine the efficacy of US counter threat financing programs globally.

Russia’s Weaponization of Energy Against Europe Since 24 February 2022, and the Transatlantic Response

As illustrated in the previous section, during the second half of 2021 and early 2022, the Kremlin capped off years of malign energy sector activities against the European continent, by taking elective steps to not take usual market actions to export natural gas volumes to European storages (including those owned in part by Kremlin-controlled Gazprom in Western Europe) – creating a natural gas crisis across the EU in the weeks leading up to Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine.

The Kremlin’s hope was that by manifesting energy as among the many hybrid threats it projected toward global democracies in the run-up to its February 2022 invasion of Ukraine, it might have undermined a resolute Western response to their aggression against Ukraine. From a wide perspective, those efforts failed.

For months we have seen the United States, along with its NATO partners and allies, continue to provide defensive military aid to Ukrainians, though more is continuously needed every day to keep Ukraine in the fight. And we have also seen an unprecedented raft of sanction actions from both Transatlantic community and global democracies to put pressure on the Putin regime to relent in its malevolent war of aggression on Ukraine, from freezing financial assets of oligarchs, to banking sector blocking measures, to initial steps to limit the ability of Putin’s Kremlin to cash in on rising oil and gas prices.

This includes Germany’s important decision to halt the certification of the Kremlin-backed Nord Stream 2 pipeline by finally including national security criteria to its assessment of the project under EU law. This was followed by the effective action by the Biden Administration imposing bipartisan, mandatory Congressional sanctions on Nord Stream 2 AG and its corporate officers in the hours leading up to the invasion, which specifically led to reports of the insolvency of the Gazprom-backed project company, and the firing of all remaining employees in March 2022.

While at least for the foreseeable future, the chapter is closed on the longstanding threat posed by Nord Stream 2 to Europe’s energy and national security, there is much that still needs to be done both to increase pressure on the Kremlin, and structurally reorient the European energy market away from its reliance on Russian oil and gas imports.

Given the significant role that hydrocarbon revenues play in funding Putin’s war-making capabilities, it is vital that the international community immediately take steps to stop this flow of money. In the early days of the war, the international community recognized that reality, and both governments and the private sector have taken steps, ranging from the Biden Administration’s effective decision to ban imports of Russian oil, gas, and coal to the US, to the exit of several energy majors – including Equinor, Exxon, BP, Shell, and others – from their Russian upstream investments.

There continues to be a recognition that the path to structurally reorienting away from dependence on Russian oil and gas remains a tall task, but that should not deter the international community from also recognizing that a wartime level of effort is needed to work as quickly as possible toward reducing and ending Putin’s ability to cash in from hydrocarbon sales.

At a top-level, a coordinated, Transatlantic energy security and sanctions policy needs to keep playing out across a three-phase approach to put further pressure on the Putin regime, and must include:

- The first phase involves continued private sector avoidance of Russian energy imports, in which global energy traders continue to largely decline to import volumes of Russian Urals crude oil for as long as they can. This has already been taking place among certain traders, as the combined threat of sanctions, reputational risk and good corporate citizenship, as well as acute physical security concerns in the shipping trade with Russia’s Black Sea ports, deterred energy traders in the opening weeks of the war.

- The second sanctions phase would then include targeted, technology-calibrated sanctions on the ability of Russian maritime vessels to export hydrocarbons to global markets, including the designation of Russian hydrocarbon shipping lines themselves – those like Gazpromflot, Rosnefteflot, and Sovcomflot.

- These interim actions would provide time for global supply chains to continue to reorient away from Russian oil and gas imports to the greatest extent possible, allowing for a third sanctions phase, including coordinated blocking sanctions on Russian state-owned oil and gas entities coupled with policies focused on diminishing Russian hydrocarbon dependence as soon as possible.

As the Transatlantic community began increasing sanctions pressure on Moscow after it’s resumed invasion of Ukraine, Kremlin-controlled Gazprom announced on April 27 that it would halt gas shipments to Poland and Bulgaria — the latest demonstration of Russia’s proclivity to weaponize its energy exports to Europe. Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov cynically described the move as responding to “unprecedented unfriendly actions” taken by nations against the Russian Federation.

Those “unfriendly actions” were an apparent refusal by Poland and Bulgaria to accept a legally-dubious “decree” signed by Putin on March 31 requiring gas payments to be made in rubles. Never mind that Poland’s state gas company PGNiG issued a statement pointing out that Putin’s gas-for-rubles scheme was neither covered in its existing contract with Gazprom nor was there even a payment due at the time.

Since that announcement, Gazprom has followed through with gas cutoffs against Finland, Denmark, and the Netherlands. While some observers have characterized Gazprom’s cut offs as a new phase of Kremlin escalation against the West as Russia invades Ukraine, the move wasn’t shocking given the aforementioned malign energy actions by Moscow toward Europe over the years.

This is just the latest move in a long-running, Kremlin-instigated gas crisis in Europe that started in mid-2021 and which allows Gazprom’s defenders — like Peskov — to perform implausible logic gymnastics to explain away the company’s behavior as “just commercial.” These extraordinary conductors of a decades-long symphony of absurdity — including figures like former German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder — have long aimed to drown anything that does not harmonize with variations on the Kremlin’s farcical refrain that “Russia has always been a reliable energy supplier to Europe.”

In the past, the decision might have caused profound consequences for both countries. It did in 2009, when the Kremlin left much of Europe freezing in midwinter. But those days are long gone because Poland and Bulgaria have been preparing, with help from the European Union (EU) and support from steadfast US energy diplomacy over the years.

Poland and Bulgaria have been able to stand by their decisions to reject Putin’s gas-for-rubles scheme and maintain support for Ukrainian sovereignty because of their long-term energy infrastructure investments, in development since Russia’s initial invasion of Ukraine in 2014. Recall that in the aftermath of Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea and invasion of Eastern Ukraine, the European Council declared in June 2014 that reducing external energy dependency would be a strategic EU priority.

In February 2015, the European Commission formalized this proposal into the European Energy Union policy framework. From that moment, a focus on advancing energy security “hardware” (energy diversification infrastructure) and “software” (market liberalization regulations) would be prioritized to reduce reliance on Russian energy resources, while battling monopolistic practices by Russian state-owned-enterprises in the European energy sector (in particular, Gazprom).

Poland hardly needed outside encouragement. In fact, shortly after the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact, it began its long-term push to cut Russian energy dependency. The past decade has seen this vision — begun in 1992 by officials including Piotr Naimski, who in recent years has served as Poland’s Plenipotentiary for Strategic Energy Infrastructure, reach fruition through the development of a myriad of projects.

This includes the Świnoujście LNG terminal, which began an operation to bring direct imports of gas to Poland in 2016, with a capacity of 5 billion cubic meters per year (bcma), and currently undergoing technical expansion to raise this to 7.5 bcma by 2023. Moreover, on May 5, just a week after Moscow’s gas cutoff started, the long-awaited 2.4 bcma capacity Gas Interconnector Poland-Lithuania (GIPL) pipeline was officially opened, followed by the May 9 arrival of the first LNG cargo delivered for Polish use via the aptly-named Independence floating storage and regasification unit (FSRU) LNG terminal at Klaipeda, Lithuania. Add to this the critical milestone reached just a day after the Russian cutoff by the 10 bcma capacity BalticPipe project, which announced the opening of the Norway-to-Denmark section on April 28, and whose link across the Baltic to Poland will be opened by October. Looking forward, Polish energy officials continue to eye the opening of an additional LNG terminal – an FSRU at Gdansk.

Poland wasn’t alone in unveiling a raft of new energy infrastructure this year. In July, just two months after Russia’s gas cutoff, and after years of careful energy diplomacy between Bulgaria and Greece, the Gas Interconnector Greece-Bulgaria (IGB) is set to come online with a capacity of up to 5 bcma from the Southern Gas Corridor. Furthermore, Greek and Bulgarian leaders met at a ceremony on May 3 that broke ground on a long-proposed FSRU LNG terminal at Alexandroupolis, Greece, with a 5.5 bcma capacity. This is slated to come online in 2023. Additionally, in the wake of the Russian gas cutoff, Bulgarian officials proceeded with booking LNG cargoes at the port of Revithoussa, Greece, to be transferred via DESFA’s Greek gas transmission system.

Because Poland and Bulgaria were prepared for Russia’s inevitable gas cutoff, it might raise questions regarding motivation for the Kremlin. In short, Moscow’s likely aim was to fire a warning shot at those countries with a higher dependence on Russian gas, and which are behind on their diversification homework, to scare (or provide an excuse to) those wishing to break ranks on Ukraine sanctions, and thereby prop up the ruble.

A prime example has played out in Hungary. While Poland has reduced its Russian energy reliance, Viktor Orbán’s government has actively sought to deepen energy ties with Russia, arguing that it is securing favorable deals. This included support for the second line of the Kremlin-backed TurkStream pipeline, as well as signing a 15-year gas supply contract with Kremlin-controlled Gazprom late last year. Likewise, the government has stalled an EU embargo on Russian oil imports.

Compared to Berlin’s long-term path to deepen its energy dependence on Russian gas, a more hopeful story is now playing out in Germany. Unlike the energy diversification policies now coming online across NATO’s eastern flank, as described above, Germany for years sought to raise its Russian dependence with the now-defunct Nord Stream 2 pipeline, while pursuing few infrastructure projects that would diversify energy dependence away from Russia. Now, in the new and highly publicized Zeitenwende era of Kremlin deterrence, things may be (slowly) changing. On May 5, Green Party Economy Minister Robert Habeck stood at a ground-breaking ceremony for Germany’s first LNG terminal at Wilhelmshaven, boldly predicting “a good chance to do what is normally impossible in Germany – to build an LNG terminal within about 10 months and connect it to the German gas supply.” Habeck also declared on May 12 that the Kremlin is using energy as “a weapon” – a true assessment of Russia’s energy games that had not been heard from previous governments in Berlin.

Regarding European sanctions on Russian energy, the announcement of the EU’s partial embargo on Russian oil in June 2022 undoubtedly was meant to send a major signal to the Kremlin that Brussels remains willing to increase costs on the Putin regime for its criminal war of aggression against Ukraine. While the measures do indicate progress to implement European sanctions on Russian energy exports, the fact that EU leaders were still unable to reach consensus on broader-reaching measures to curb purchases of Russian hydrocarbons – including full oil sanctions, as well as initial steps against gas imports owing to objections from Budapest – means that Moscow will continue to feel insufficient pressure to relent in its ongoing atrocities against Ukrainian sovereignty.

Reports have suggested that the wind-down period toward implementation of this partial oil embargo – which would limit Russian maritime oil exports to the EU by the end of the year – will still allow the Kremlin to cash in on its remaining oil sales to Europe in the short term, and on this front there has been a missed opportunity to implement some of the ideas that have been put forth on special interim regimes – like energy payments held in escrow accounts, or tariffs on Russian oil products – that would discourage purchases of Russian resources, while limiting the ability of the Kremlin to access funds associated with oil sales as the EU ramps down imports in line with these announced measures.

The EU has thus far missed an opportunity to also message near-term measures that would further tighten transatlantic energy sanctions against the Kremlin. These include announcing an end date for Kremlin-controlled Gazprom’s natural gas pipeline projects like Nord Stream 1 and TurkStream 2, as well as ending Rosneft and Gazprom ownership of critical energy facilities across Western Europe. Nevertheless, the partial oil embargo is a tangible step forward, though the EU should immediately resume the task of critical energy diplomacy to secure further restrictive measures to limit the Kremlin’s ability to use hydrocarbon revenues to fund its war machine.

Increasing Energy Sanctions Pressure on the Kremlin and Ending European Energy Dependence on Russia

Given the ongoing energy security policies discussed in the previous sections, the following recommendations should be taken to increase pressure on the Kremlin to relent in its ongoing aggression against Ukraine, while ending European energy dependence on the Russian Federation:

- Dramatically increase Transatlantic energy sanctions on the Putin regime:

As discussed in the previous section, the Biden Administration’s laudable complete ban on hydrocarbon imports to the United States from the Russian Federation has not yet been matched by our European partners and Allies. While the European Union has passed a partial embargo that will ban all maritime imports of Russian oil to the bloc by the end of the year, this action falls far short of what is urgently needed to bring significant pressure against the Kremlin.

While the main objective of any sanctions regime on Russian energy must be to enable a full embargo on Russian oil, gas, coal, and refined products, urgent interim measures can be taken to both reduce the amount of funds the Putin regime receives from remaining energy sales en route to zero, while signaling to the Kremlin that the shift away from Russian energy dependence in the European Union will be a permanent, strategic shift away from decades of vulnerability to Russian energy coercion.

Given the history of US and EU energy policy with respect to Russian energy export pipelines to the European continent, actions must now be taken to ensure that the Kremlin’s primary conduits of energy leverage over Europe are phased out permanently. This must include announcing end dates for Gazprom’s Nord Stream 1, TurkStream Line 2 (for EU exports), and Yamal-Europe natural gas pipelines, ultimately followed by ending Russian gas transit via the Ukrainian gas transmission system itself as a last phase in this process of weaning Europe off Russian gas dependency. In particular, the US and EU should take sanctions measures to make sure that these pipelines, in addition to the now-suspended Nord Stream 2 pipeline, are sanctioned to block any potential future efforts to revive these pipelines linking the democratic EU to an authoritarian Russian Federation.

As a member of the International Working Group on Russia Sanctions organized by Ambassador Michael McFaul at Stanford University, I have coauthored and endorsed with a group of US, Ukrainian, and international sanctions and energy experts a report recommending additional energy sanctions that can be taken to immediately increase pressure on the Putin regime. A few key recommendations from the report on Russia energy sanctions actions are quoted as:

- Announce the near-term decommissioning date for Gazprom’s Nord Stream 1, TurkStream Line 2 (for EU exports), and Yamal-Europe [natural gas] pipelines.

- An adjustable import tax (or tariff) designed to transfer substantial funds away from Russian and/or Belarusian exporters [of oil] for the purpose of sharply reducing export revenues for the war and providing monies for Ukraine reparations (a “value-transfer mechanism”). Under this mechanism, Russian and Belarusian exporters may sell to EU buyers, provided the buyers remit all payments to a designated EU Payment Authority. The Payment Authority will net out any tariff or tax assessed, which will be allocated to a special account to fund Ukrainian reparations. It can be administered by the EU (a “Controlled Sales Regime”).

- Separate value-transfer mechanisms will be maintained for each category of imported crude oil and oil products. The EU will find it easier to substitute some categories of oil imports, such as sour crude, than others, such as diesel. To provide targeted incentives for products in short supply, the Payment Authority will maintain a separate value-transfer mechanism for each major category of oil imports (e.g., Urals blend, Siberian light, fuel oil, diesel, and others). Thus, the EU can increase or decrease the net payments on any particular category based on prevailing market conditions at any given time. Such a mechanism can be implemented either in the form of a simple value- or price-based tax, or as a more nuanced system.

- A special escrow account will hold net proceeds due to exporters. The Payment Authority could deposit any net sale proceeds into a special escrow account in approved European banks for the benefit of the exporter. Those proceeds could remain in escrow until an appropriate time following the cessation of hostilities. A portion of escrowed funds may be accessed sooner, such as for humanitarian purposes, at the EU’s discretion.

- Controlled Sales Regime [for Russian gas exports]. Impose a levy on Gazprom for sales into the EU and retain the balance of payments in escrow accounts in a manner similar to the one described…[for]…oil above.

- Targeted sanctions against material-service providers enabling seaborne exports aimed at circumventing the Controlled Sales Regime. To discourage any large-scale efforts to circumvent the Controlled Sales Regime, the EU (in conjunction with the United States and the United Kingdom) should impose sanctions on service providers enabling seaborne exports to non-EU consumers. These service providers could include, but are not limited to, maritime insurers, banks, commodities traders, vessel chartering firms, commercial certification providers, technical support and maritime engineering firms, and offshore vessel tethering and ship-to-ship transfer support services providers. Most of these service providers for the Russian-oil seaborne trade have traditionally been based in Europe.

- Further sanctions on Russia’s oil sector. Existing sanctions on oil-field services and technologies should be expanded to include all oil-field services and technologies for any oil-exploration and production projects within Russia, not just shale, deep-water, and Arctic offshore projects. EU and US nationals working in senior executive positions in the Russian oil and gas sector should be subject to individual sanctions.

- Develop and deploy critical energy diversification infrastructure and policies that will make Europe independent of Russian energy going forward:

In addition to sanction measures to immediately increase pressure on the Putin regime to end its war of aggression against Ukraine, the US should assist the European Union in further accelerating a long-overdue strategic reorientation toward full independence from Russian energy resources.

In the immediate term, this policy must be focused on creating the energy diversification infrastructure and import capacity to replace Russian oil and gas imports as soon as possible, swapping Russian volumes with energy cargoes from alternative global suppliers. To support this infrastructure goal, the US should commit to further supporting European initiatives that are aimed at deploying energy diversification infrastructure, including via the Three Seas Initiative.

Additionally, given the correct focus that has been underway for months to increase NATO’s defense posture along its eastern flank, it is important that the US work with NATO and EU member states to expand and create operational resiliency in the existing NATO pipeline network.

Likewise, especially with the end of the heating season in Europe upon us, actions to ensure that sufficient gas storage volumes are acquired across Europe ahead of the next heating season beginning in the Autumn must be prioritized. This includes expanding LNG import capacity, as well as completing additional import pipelines from new or expanded natural gas production sites around the periphery of the EU.

Infrastructure options such as LNG floating storage and regasification units (FSRUs) at strategic locations (such as in Brunsbuttel and Lubmin, Germany, and Gdansk, Poland) around the European coastline, should be prioritized over larger-scale permanent infrastructure that would take longer to develop. Furthermore, a wartime level of effort and funding should be allocated to construct the needed onshore infrastructure associated with each FSRU that would normally take years of project development, prioritizing locations where significant requisite onshore infrastructure already exists to aid in the speed of deployment.

A focus must also be placed on ending the ownership positions of Russian state-owned energy enterprises and their subsidiaries from partial or majority ownership stakes in critical European energy refinery and storage facilities. For example, on the European natural gas front, the European Union should focus on evicting Kremlin-controlled Gazprom from ownership stakes in critical gas storage facilities across Western Europe. If left unaddressed, there is a high potential for issues ranging from conflicts-of-interest to strategic security concerns, as Russian state-controlled ownership stakes in these facilities might impede the necessary buildup of gas volumes for the Winter – which is exactly what led to the European gas crisis in late-2021 and early-2022 across Europe, as mentioned in the description of Russia’s weaponization of energy over that period in the previous sections.

While Europe’s energy security focus must remain on hydrocarbon swaps for existing Russian hydrocarbon reliance to avoid broader European energy insecurity on the shortest possible term, the European Union must also rapidly increase its design, deployment, and operationalization of renewable energy infrastructure as soon as possible.

Given the longer-term nature of renewable deployments, these systems may not be enabled fast enough to provide large-scale alternative energy sources to Russian energy by the end of this year, but they must nevertheless be deployed now with all speed. To address the climate crisis, renewable energy deployments must continue to be a central focus of Transatlantic energy infrastructure development, though this must happen in a manner that doesn’t lead to energy insecurity owing to the state of the global energy market owing to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, since prolonged energy insecurity could dampen the public support needed to ensure a successful energy transition away from hydrocarbon reliance.

Nevertheless, like the hydrocarbon diversification projects proposed above, renewable energy systems should be funded with a wartime level of support to fast-track deployments. Over the longer term, these systems will be instrumental in making EU reliance on Russian energy resources permanent and irreversible, while simultaneously reducing carbon emissions needed to combat the climate crisis.

In addition, US Congress should support collaborative basic science and technology research with global democracies including across Europe to increase the speed with which transformational low-and-zero-carbon energy technologies are developed, from higher-efficiency “traditional” renewable energy systems, to the realization of commercially-viable terrestrial nuclear fusion energy production in the coming decades enabled through consistent support for basic high-energy density physics programs in the years to come.

As a member of the International Working Group on Russia Sanctions organized by Ambassador Michael McFaul at Stanford University, I have coauthored and endorsed with a group of US, Ukrainian, and international sanctions and energy experts a report recommending additional energy sanctions that can be taken to immediately increase pressure on the Putin regime. A few key recommendations from the report on energy diversification policy actions are quoted as:

- Increase European ownership over critical infrastructure. A vigilant focus on infrastructure dependency in Europe is necessary to safeguard national security and energy policy. Ownership by Russian state-owned enterprises of European critical infrastructure poses a security risk that needs to be addressed before Europe’s moment of maximum vulnerability next heating season. Across Europe, Gazprom owns critical gas storage facilities, while Rosneft owns refineries. Classifying facilities as national security infrastructure and requiring Russian divestment will mitigate risks to energy security and ensure greater European control. The EU-wide investment controls’ mechanism needs to be strengthened.

- Install floating storage and regasification units (FSRUs) to allow additional LNG supply with a wartime level of investment and approval speed to ensure increased capacity of LNG to flow to European gas storage before the next heating season.

- Consider the rapid development of FSRUs at locations currently proposed for LNG import facilities, including Gdansk in Poland, and Wilhelmshaven and Brunsbuettel in Germany, as well as at locations where existing infrastructure could be leveraged.

- Take development steps to convert and repurpose the current Nord Stream 1 and 2 landing site facilities at Lubmin, Germany to instead link to FSRU-based non-Russian LNG imports.

- Accelerate wind and solar deployment. In addition to increasing the utilization rate of nuclear, coal and biomass plants, the EU should promote the acceleration of wind and solar deployment, including by addressing delays with permitting.

- The financial incentives for rooftop photovoltaic systems installation would reduce both consumer bills and demand for gas in the residential sector.

- Accelerating the adoption of renewables will reduce gas consumption in a manner fully consistent with long-term EU objectives and will allow for the faster (and permanent) retirement of the coal fleet called into short-term service.

- Curbing Kremlin Strategic Corruption and Elite Capture in Western Democracies:

While many of the prominent, former senior European officials have left or are in the process of leaving their post-government positions working for Kremlin state-owned-enterprises in recent weeks, including prominent state-controlled energy entities like Gazprom and Rosneft, the trend has not reached a definitive end.

For example, absent policy or legislative guardrails, it remains unclear if this practice would largely resume at some point in the future, were there suddenly a ceasefire between Russia and Ukraine tomorrow. The policy developments also don’t consider the threat of similar elite capture or strategic corruption trends to continue from other authoritarian nations, like China, in the future. I have written about the dangers of Kremlin elite capture and strategic corruption manifested via post-government positions for Western officials at Kremlin-controlled energy enterprises for the Atlantic Council coauthored with Anders Aslund on 11 March 2021, as well as for Foreign Policy magazine coauthored with Paul Massaro on 29 December 2021.

To ensure that the trend of former officials from global democracies working for authoritarian nations after their government service is ended once and for all, US Congress, in coordination with our partners and Allies can take two immediate steps. As I outlined with co-author Casey Michel in Foreign Policy magazine on 15 February 2022, these include:

- Immediately define a Transatlantic norm against post-government employment for Russian state-owned-enterprises. Even if currently legal in Western jurisdictions, the practice of “Schröderization” can rapidly erode public confidence in Western leaders’ commitment to stand up to authoritarian nations like Russia in the long term. Given that legislative action, especially that coordinated with EU parliaments, would likely be a lengthy process, a statement of policy intent should be made immediately to create a chilling effect on any future former Western officials considering employment by Russian state-owned-enterprises. The US Congress and European Union parliaments can immediately issue a joint statement vowing to work toward synchronized legal actions and norms. This statement could happen today and shouldn’t be a controversial position for all US policymakers to readily endorse.

- Pass the Stop Helping America’s Malign Enemies (SHAME) Act. The US Congress should immediately begin the process of drafting and enacting the SHAME Act, which would ban former US government officials from seeking employment by Russian state-owned-enterprises or their subsidiaries following government service. This will be a lengthier process, with valid concerns about everything from the status of existing contracts to the classification of authoritarian regimes and proxy entities. Indeed, defining a full set of Russian state-owned-enterprises, subsidiaries, and proxy entities would need to include well-considered thresholds for classification. But by passing the SHAME Act, the US Congress would be setting out a legislative roadmap with which other global democracies can emulate and synchronize. Ultimately, this norm can and should be expanded to other authoritarian regimes whose actions are antithetical to open-market, liberal-democratic societies.

Conclusion

If there is one reality of modern energy diplomacy, it is the way that the discipline illustrates that modern national security issues are increasingly multidisciplinary and require a significant level of technical – including science and technology – expertise infused into the traditional diplomatic process to address these modern international challenges. Far from performing a markets-only analysis — what I often call “the Bloomberg terminal approach” — to understand energy dynamics as emerging from and having impacts strictly within economic systems, a broader analytic framework is required to assess how authoritarian nations like Russia weaponize energy and a myriad of other levers of state control. This must include not only economics, but an understanding of geopolitical motives, national security impacts, and transnational kleptocratic trends, all on top of a robust grasp of the technical realities of the resources and energy infrastructure project developments themselves.

For years, the United States has pursued what could be called an anticipatory diplomatic approach to European energy security – showing a willingness to look over the horizon to assess risks and engage on potential solutions with stakeholders from a variety of disciplines to help mitigate future energy insecurity. This includes both US Congress and successive US Administrations over the past decades, who have been correct in warning Europe about the risks of over-reliance on Russian energy resources and advancing policies to help our partners and Allies across Europe reduce this strategic dependency. Given the long-term project development arc of energy infrastructure, this anticipatory approach has been successful in supporting the development of energy diversification infrastructure over the last decade across Central and Eastern Europe to make countries like Poland and Bulgaria largely resilient to Russia’s current gas cutoffs of their nations. Thus, an anticipatory diplomatic model needs to continue to be the overarching policy model taken by Washington to help support Europe’s energy security.

Likewise, US Congress has displayed the correct instinct on forwarding Russian energy sanctions legislation since Russia’s initial invasion of Eastern Ukraine and illegal occupation of Crimea in 2014, including three-times passing legislation by overwhelming, bipartisan, bicameral majorities aimed at stopping the Kremlin-backed Nord Stream 2 pipeline in 2017, 2019, and 2020.

With this history in mind, there is a wealth of US expertise and experience on supporting effective policies now pursued by our European partners and Allies to draw upon, both for continuing the urgent push to help our European friends become independent of Russian energy coercion, while pressing for measures to limit the funds that Russia continues to receive for its energy sales to Europe, pushing the Putin regime to abandon its aggressive, neo-colonial ambitions in Ukraine.

For the sake of Ukraine’s struggle, we must ensure that reason will prevail and result in effective energy security policies to counter Russian malign energy activities across the Transatlantic community. For the sakes of those millions of people now exposed to the Kremlin’s malice, failure is not an option.

Thank you for your attention, and I look forward to answering your questions.

The views expressed in this written testimony are those of the author and do not represent those of the organizations they are affiliated with.